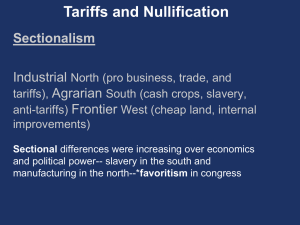

A Tale of Two Tariff Commissions - Inter

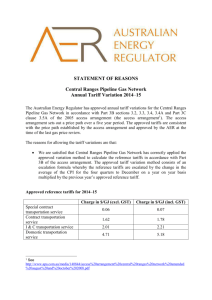

advertisement