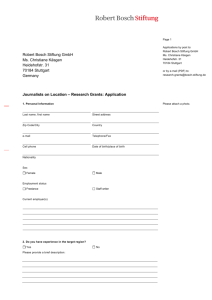

The Carl Friedrich Goerdeler-Kolleg of the Robert Bosch Stiftung

advertisement