The Tuskegee Airmen – Reaching New Heights

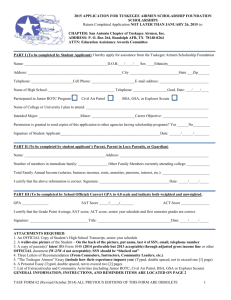

advertisement

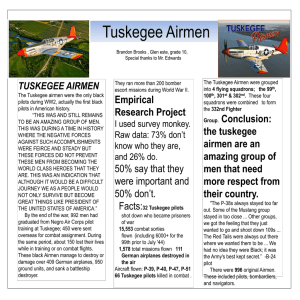

Nguyen 1 Michelle Nguyen Ms. Solomon National History Day 14 December 2015 The Tuskegee Airmen: Reaching New Heights The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African American aviators in the US Armed Forces. They consisted of the 99th fighter squadron, the 332nd fighter group, and the 447th bombardment group who all trained at the Tuskegee Army Airfield. These heroes faced racism and prejudice before, during, and even after the end of World War II. The airmen excelled in combat and bomber escorts. They were proof that African Americans could fly. Being the first black pilots in the US Army, they opened the door to aviation for all African Americans. These aviators have gone down in history as the first African Americans in the US Army Air Force. The Tuskegee Airmen exchanged proof that they could fly in order to gain the chance of serving as pilots in World War II, encountered racism against black aviators in the US Armed forces, and explored aviation. World War II started in 1939 when Adolf Hitler invaded Poland, but the United States of America officially joined the war in 1941 when Japan bombed the Pearl Harbor naval base (Royde­Smith). At the beginning of the war, the secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Walter White, requested and was denied the formation of black air squadrons. Later that year, Public Law 18 was passed and this initiated flight training for African Americans in schools such as Tuskegee Institute. Even though there were trained black Nguyen 2 aviators, they were not permitted to join the army (Patel). The Army Central Staff College conducted a study in 1925 about black soldiers’ records to determine the best way to use blacks in the army. They concluded that blacks were “cowards and poor technicians and fighters, lacking initiative and resourcefulness” (Harris 19). Therefore, a common belief at the time was that African Americans were not intelligent or skilled enough to become strong military leaders and pilots (National Park Service). The Tuskegee Airmen proved this belief wrong. The Tuskegee Airmen exchanged proof that they could fly in order to gain the chance to serve as African American pilots in World War II. “Many people thought the so­called Tuskegee Experiment would fail, but instead, the African American fliers were determined to prove them wrong” (Booker). They had to complete primary, basic, and advanced classes that included aeronautics, navigation, flying formations, forced landings, and other necessities before they could graduate and become part of the US army. In 1942, five African American men graduated the first class of the Tuskegee Army Airfield (Patel). Among the five graduates, was Benjamin O. Davis Jr. who would later become the first African American US Air Force general (Altman). This proved the ideology that blacks were too unintelligent and unskilled to become effective aviators, wrong. These aviators became the first black US pilots to form the 99th fighter squadron after they proved themselves capable and the opportunity of being an army pilot opened up to all African Americans. In the end, the Tuskegee Airmen flew 1,578 missions, 15,533 sorties, destroyed 261 enemy aircraft, and won over 850 medals while also battling racism (“Tuskegee”). Along with the circulating assumption that blacks could not fly, these airmen also endured racism and prejudice against them. Nguyen 3 The Tuskegee Airmen encountered racism and prejudice against black aviators in the United States Armed forces. In 1936, Benjamin O. Davis Jr. graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point, ranking 35th in a group of 276, but was denied from Army Air Corps because he was black ( "Military" ). About five years later, the Tuskegee Institute became a training facility specifically for African American fliers who wanted to join the army. The town of Tuskegee, Alabama, was racist, discriminatory, and strictly segregated (Harris 33). Flight training for the African American cadets was difficult from the start because high levels of education were needed so many candidates were “washed out”. They were given poorly maintained and old equipment and aircraft. Because of strict segregation, the cadets could not receive advice from white pilots who experienced combat. “The haphazard assignment of pilots and technicians showed the War Department’s inclination to waste time and money rather than include blacks in the air corps” (Patel). After the airmen returned home from the war, they still experienced constant discrimination and most had to give up flying to get different jobs because there were no other jobs available to African American pilots (Edna). Tuskegee Army Air Field closed down in 1946 when local whites demanded that the base was run by white officers or else it should close ( Caver 131). Despite their encounter with racism and prejudice, these fliers were the first group of black fliers in the United States to delve into the world of military flying. The Tuskegee Airmen explored aviation in the skies of World War II as African American pilots. The first African American pilot to fly the first lady was flight instructor, Charles Alfred Anderson, who flew the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, around Alabama when she visited the Tuskegee Institute in 1941 (“Eleanor”). Stationed overseas in North Africa and Europe, they flew P­40 combat planes and performed numerous sorties and strafing duties and Nguyen 4 escorted bombers (Patel). The Tuskegee Airmen initially only flew close support missions in the tactical air force before they were eventually re­assigned to bomber escort missions when too many bombers were shot down. “The white fighter pilots were not staying and sticking with bombers, they were off looking for their own personal victories” recalled Tuskegee airman, Harold Brown ( Brown ) . The 99th fighter squadron joined the 332nd fighter group which consisted of the 100th, 301st, and 302nd squadrons, and together, they never lost a bomber to enemy aircraft (Altman). Being the first African American aviators in the United States Army Air Corps was an important step in getting equal rights for all African Americans. The Tuskegee Airmen were a topic important in history because they helped drive the African American race forward. Harold Brown, a Tuskegee airman recollected, “We (the Tuskegee airmen) were the guys that, initially back in 1939, the (war) department said we were too dumb and not smart enough to fly an airplane, but we became one of the most reliable and one of the finest outfits they had in the 15th air force” (Brown). When people doubted the airmen's flying abilities, they went above and beyond by becoming extremely dedicated and successful pilots. Encountering racism on a daily basis did not stop these men from achieving their goals. The 447th bombardment group often challenged segregationist policies and started a legal battle called the Freeman Field mutiny when they tried to enter a white officers’ club (“Freeman”). Recently, the airmen are being recognized by the nation and are wanted as guest speakers even though they were barely acknowledged directly after the war (Barnard). The pilots received a lot of attention and many awards, such as the congressional gold medal that was awarded to them by President George W. Bush in 2007 (Kruzel). The Tuskegee Airmen eventually helped desegregate the US Military when Harry S Truman created Executive Order Nguyen 5 9981 in 1948. The 926 pilots, 58 artillerymen, 136 navigators, and 261 bombardier­navigators formed the first group of African American aviators in the US Army Air Force and paved the way for future black pilots in the military (Patel). All in all, these airmen will be remembered for their numerous brave efforts. African American pilots who trained at Tuskegee Army Airfield exchanged evidence with the world that they could fly in order to have the possibility of being in the US Armed Forces, encountered prejudice, and explored the sky during World War II. The airmen had many encounters of racism and prejudice along the way. The sky of aviation was previously unknown to black United States Army pilots, but that was explored by the Tuskegee Airmen. The exchange between the US Army and the Tuskegee Airmen allowed black US army pilots to fly because they knew that it was possible. Even seventy years after the end of World War II, these fliers are still making an impact on today. The Tuskegee Airmen were inspiring African Americans pioneers who courageously fought racism and prejudice to serve their country in the US Armed forces and set a foundation for all black pilots of the future. Nguyen 6 Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources "99th Squadron Gets New Leader." Philadelphia Tribune (1912­2001) : 5. Jan 31 1942. ProQuest. Web. 12 Nov. 2015 . < http://search.proquest.com/hnpphiladelphiatribune/docview/531612040/C330FF769CF1 4F39PQ/7?accountid=70954 >. This newspaper article written in 1942 is about an interview with Lt. Colonel Frederick V. H. Kimble who was relieving the previous commanding officer at the Tuskegee Army Airfield. He believed in the flight training program for African Americans and was greatly interested in the education of these pioneers. This primary source shows that, although the Tuskegee Airmen were faced with a lot racism and prejudice, they also had supporters backing them too. "Air Force Plans to End Segregation." Philadelphia Tribune (1912­2001) : 1. Jan 18 1949. ProQuest. Web. 14 Nov. 2015. < http://search.proquest.com/hnpphiladelphiatribune/docview/531822147/805BBDD6169 54E4APQ/12?accountid=70954 >. This primary source is an article written in 1949. It is about the desegregation of the United States Air Force which happened because of the executive order that the president passed in 1948. This is important because black aviators will no longer be segregated and will stand alongside white pilots instead. Brown, Harold. Personal Interview. 5 Dec. 2015. Nguyen 7 This is a phone interview that I conducted with Harold Brown who joined the Tuskegee airmen when he was 19 years old. He talked about how he first became a Tuskegee airman, how racism was still present after he returned home from the war and recognition in the media. He also recounted several personal stories about some of his most memorable flight missions, encounters with racism in the south, and how he became a prisoner of war in Germany. This interview let me hear about the legacy of the Tuskegee airmen through the eyes of someone who experienced it. I incorporated a quote from Brown that explained how the Tuskegee airmen proved to the world that blacks can fly aircraft. "Dispossess Notice?: Watch Move To Make Tuskegee Air Field Training Place For British Flyers" Philadelphia Tribune (1912­2001) : 20. Dec 27 1941. ProQuest. Web. 7 Nov. 2015 . < http://search.proquest.com/hnpphiladelphiatribune/docview/531608395/805BBDD6169 54E4APQ/3?accountid=70954# >. This newspaper article was written in 1941 when the 99th fighter squadron was training at the Tuskegee Air Field. There were rumors about British pilots being assigned to the airfield at Tuskegee to train for war time flying. This could have caused the African American cadets and crew to be moved elsewhere. This primary source stresses how important the black cadets training to be army pilots were because many people did not want them to be relocated for the sake of white pilots. Edley, Steve. "Aircorp Man Drops Music to Clear Skies of Nazis." Philadelphia Tribune (1912­2001) : 11. Feb 10 1945. ProQuest. Web. 10 Nov. 2015 . Nguyen 8 < http://search.proquest.com/hnpphiladelphiatribune/docview/531828772/805BBDD6169 54E4APQ/8?accountid=70954 >. This primary source is a newspaper article written by Steve Edley who interviewed Tuskegee Airmen, Capt. Carter and Lt. Delz. Capt. Carter. attended Tuskegee Institute prior to signing up for the army. and Lt. Delz majored in education and was a musician in the Portland Symphony. This source shows that the Tuskegee Airmen were made up of all kinds of people who were interested in joining the US Air Corps regardless of occupation. "Jim Crow Air Squadron Denounced by National Airmen's President." Philadelphia Tribune (1912­2001) : 3. Feb 20 1941. ProQuest. Web. 12 Nov. 2015. < http://search.proquest.com/docview/531571324/28451DA3AD804B03PQ/1?accountid= 70954 >. This newspaper article is written about Cornelius R. Coffey, the National Airmen’s association’s president. Coffey supported integration into the US Air Corps but he did not support the setup of Tuskegee Institute’s program. He believed that the pilots that would be trained there would not be able to compete with white pilots. This primary source provides one of the many different views on the Tuskegee Institute’s plan to train black aviators. Roosevelt, Franklin D. "FDR Letter to Walter White." Letter to Walter White. 14 Oct. 1944. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum . N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2015. < http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/education/resources/pdfs/tusk_doc_f.pdf >. Nguyen 9 This primary source is a letter written by Franklin D. Roosevelt to Walter White, the secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He discussed concerns about how African American veterans would be treated after the war. He also wrote that White could arrange to meet with General Hines to help assure that Black veterans would not face any discrimination based on their race. This letter helps us understand how much opposition there was about having African Americans serve in the army, including the Tuskegee Airmen. The United States of America. Executive Branch. White House. Executive Order 8802 . By Franklin D. Roosevelt. Washington D.C.: White House, 1941. Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidenital Library and Museum . National Archives and Records Administration. Web. 25 Sept. 2015. < http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/education/resources/pdfs/tusk_doc_b.pdf >. This executive order issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1941 banned discrimination against anyone in the United States army regarding their race, including African Americans aviators. This is an important document because it allowed the formation of the program at Tuskegee Institute that trained black pilots. Nguyen 10 Secondary Sources Altman, Susan. "Tuskegee Airmen." Encyclopedia of African­American Heritage, Second Edition . Facts On File, 2000. African­American History Online . Web. 15 Oct. 2015. < http://online.infobase.com/HRC/Search/Details/158633?q=tuskegee airmen >. This secondary source gives a basic overview on the Tuskegee Airmen. It lists the locations where the pilots were deployed overseas and the awards that they received. In my essay, I mentioned that Benjamin O. Davis Jr. would become the first black United States Air Force general and how the 332nd Fighter Group never lost any aircraft to the enemies. Barnard, Anne. "Tuskegee Airmen Embrace Their Past." The New York Times . The New York Times, 24 May 2009. Web. 24 Sept. 2015. < http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/25/nyregion/25tuskegee.html?_r=2 >. Barnard interviewed former Tuskegee airman, Julius Freeman. He spoke about how he distanced himself from his experience of being Tuskegee airman when he discovered that racism had not changed. He became a successful vintage car dealer. The article also follows up on other former airmen and how they adjusted to civilian life. This article gave me an insight about how life was after the war for some former Tuskegee airmen. In my paper, I wrote about how the pilots are receiving attention and are wanted as speakers now even though they were not receiving attention directly after the war. Caver, Joseph, Jerome Ennels, and Daniel Haulman. The Tuskegee Airmen: An Illustrated History, 1939 ­ 1949 . Montgomery, AL: NewSouth, 2011. Print. Nguyen 11 This book consisted of a lot of old photographs concerning the Tuskegee Airmen. It also had detailed information about the timeline of the airmen in chronological order. This book was a good place to start my research and gave me a broad and basic understanding of the legacy and achievements of the Tuskegee Airmen. I wrote about how the Tuskegee Army Air Field was forced to close because the white population did not want it to be commanded by officers that were not white. "Eleanor Roosevelt and the Tuskegee Airmen." Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum . Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2015. < http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/aboutfdr/tuskegee.html >. This web page focuses on First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s involvement with the Tuskegee Airmen. There are also some primary sources such as letters and pictures. She was interested in the progress of the airmen and supported them. I used information about Eleanor Roosevelt’s flight with Tuskegee airman, Charles Alfred Anderson, in my essay. Edna, Jodi. “Veterans Who Fought War ­ and Bias.” The Philadelphia Inquirer 29 Dec. 1991: 1+. Print. This secondary source is a newspaper article that includes some Tuskegee airmen’s personal experiences with racism before, during, and after World War II. The airmen had a hard time becoming a pilot because of the lack of opportunities for African Americans. Even when they were pilots in the army, they were still treated worse by others because of their race. After the war ended, the airmen received no more missions and found it difficult to find jobs. Most had to give up flying and get other jobs. This newspaper Nguyen 12 article is important because it focuses on how the Tuskegee airmen had to fight a war and racism too. "Freeman Field Mutiny." Red Tail Squadron . Red Tail Squadron, n.d. Web. 1 Nov. 2015. < http://www.redtail.org/the­airmen­a­brief­history/feeman­field­mutiny/ >. This secondary source summarizes the Freeman Field Mutiny in 1945. This event was conducted by the airmen in the 447th Bombardment Group. They entered a white officers’ club in groups of three but all 103 pilots were arrested. This incident is a major step in integrating the United States military. I mentioned this event in my essay as an example to show how some of the Tuskegee Airmen fought racism in the army. Harris, Jacqueline L. The Tuskegee Airmen: Black Heroes of World War II . Parsippany, NJ: Dillon, 1996. Print. This is a detailed book written about the Tuskegee Airmen. It includes historical background about black aviation and has many pictures and maps. This book focuses on the airmen, important events that affected them, the racism that they experienced, and their reception after World War II. I wrote about a study that was conducted before Tuskegee Institute started training black pilots that concluded that blacks were not smart enough to be good military fliers. I also mentioned the racism and prejudice in the town of Tuskegee, Alabama. Kruzel, John J. "President, Congress Honor Tuskegee Airmen." U.S. Army The Official Homepage of the United States Army . N.p., 30 Mar. 2007. Web. 27 Sept. 2015. < http://www.army.mil/article/2476/President__Congress_Honor_Tuskegee_Airmen/ >. Nguyen 13 This article was written in 2007 about President George W. Bush awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to the Tuskegee Airmen. Kruzel also quoted President Bush’s and the commander of the 100th Fighter Squadron, Dr. Roscoe Brown’s, thoughts about the distinguished award being awarded. The article also touches upon the fact that the Tuskegee Airmen are still being recognized long after World War II. I incorporated the president awarding the airmen the Congressional Gold Medal into my essay. "Military Pioneer, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr." African American Registry . N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Dec. 2015. < http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/military­pioneer­benjamin­o­davis­jr >. This secondary source gives the basic biography of Benjamin O. Davis Jr., one of the first Tuskegee Airmen, from his birth to his death. It includes information about how Davis started flying, his accomplishments, records, and awards. In my paper, I wrote about how racism affected Davis when he was denied from the Army Air Corps because of the color of his skin. National Park Service. "Significance of the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site." National Parks Service . U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. Web. 8 Oct. 2015. < http://www.nps.gov/tuai/learn/historyculture/significance­of­the­tuskegee­airmen­nation al­historic­site.htm >. This web page sums up several important facts and events regarding the Tuskegee Airmen. It discusses the airmen’s impact on racism in the military and their military achievements. I incorporated a quote about the common belief that African Americans were not capable of flight into my essay. Nguyen 14 Patel, Abha Sood. “Tuskegee Airmen.” Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty­first Century, Edited by Ed. Paul Finkelman. Oxford African American Studies Center, http://www.oxfordaasc.com/article/opr/t0005/e1188 (accessed Wed Sept 30 08:59:41 EDT 2015) This packet provides a general overview spanning the full course of the Tuskegee Airmen’s era. There is a large amount of details, names, and dates concerning the achievements of the pilots. I used information about how trained black pilots were not allowed to enter the army, the kind of missions they flew overseas, and the number of pilots, navigators, and bombardier­navigators. I also quoted about how the war department did not deploy the airmen because they did not believe in black army fliers. Royde­Smith, John Graham. "World War II." Encyclopedia Britannica Online . Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 1 Nov. 2015. < http://www.britannica.com/event/World­War­II >. This website has a detailed overview on events in World War II. It is essential to my paper because it provides historical context on the Tuskegee Airmen such as the start of World War II and America’s involvement. "Tuskegee Airmen." Britannica School. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2015. Web. 1 Nov. 2015. < http://school.eb.com/levels/high/article/2992 >. This web page has summarizes the history of the Tuskegee Airmen and also has specific detail and dates about certain events. It talks about the fliers’ training and missions as well as the aircraft. In my paper, I used the records about the total number of missions and sorties flown, enemy aircraft destroyed, and medals earned.