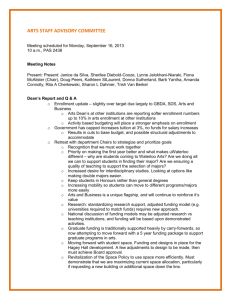

Balancing Market and Mission - DePaul University Resources

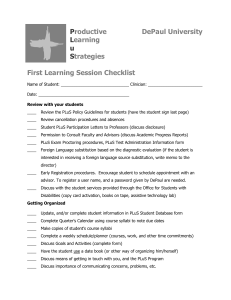

advertisement