The Process: You will get an objection from

advertisement

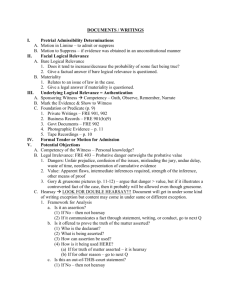

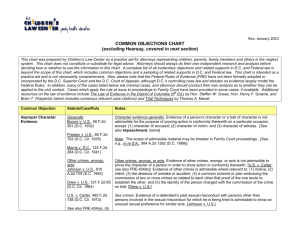

BASIC EVIDENTIARY OBJECTIONS AND RESPONSES FOR ROUND ONE TRYOUTS The Process: You will get an objection from opposing counsel, directed to the judge. At that point, the judge might choose to decide the issue herself (i.e., just say “overruled” or “sustained”), or ask you for a response. You respond to the judge, not to opposing counsel. Remember, we are much more interested in whether you can get an objection, recover, and move on, rather than having the perfect response, so don’t be afraid to give a response, get the judge’s ruling, and move on. If the response is to sustain the objection (that is, agree with the opposing counsel), be ready to stop, think, and most likely rephrase the question or move on to the next question. For example, if you get a leading objection on direct examination, simply rephrase as an open-ended question. Alternatively, if a 602 objection is sustained for lack of foundation, go back and ask a couple foundational questions to establish that the witness does, in fact, have personal knowledge. The Objections: Please pick up a mini book of evidence outside the Mock Trial office to review these rules. For round one, the following objections are possible during your delivery or examination, with the relevant Federal Rule of Evidence (“FRE”) number in parentheses: – Relevance (401-402) – Prejudice / Confusion (403) – Character (404-06) – Personal Knowledge (602) – Hearsay (800’s) Also, since you should not ask leading questions on direct examination, we may object with “objection, leading” (which is technically an FRE 611 objection). The response is to say, “I can rephrase the question, your honor,” then do so. For example, assume you asked the leading question, “the car was red, wasn’t it?” on direct. After the leading objection is sustained, you simply rephrase the questions as, “what color was the car?” Sample Objections and Responses Below are a list of basic objections and basic responses. This is not a substitute for the substantive aspects of the rules of evidence, nor should it be considered an exhaustive list. Objections are organized by topic, and include citations to the pertinent Federal Rules of Evidence. Moreover, the model responses are stated as mere assertions, and are meant to be supplemented by facts and circumstances which support the response offered. Examples are also provided for some rules, but realize that these use facts relevant to the specific case. Relevance (FRE 401, 402) Evidence needs to be “relevant,” which is defined as having any tendency to make a fact or consequence more or less probable. It is a very low threshold; you just respond by showing that the answer will tend to make some “fact of consequence” more or less likely. • Objection: Relevance • Response: The evidence is relevant because it tends to show [fact of consequence]. Example: L1: Mr. Snyder, you’re in school, right? CS: Yes. L1: If you lost your job at the rink, you’d have to drop out, isn’t that right? L2: Objection, relevance. Judge: Response? L1: Your honor, this tends to show that Mr. Snyder has a reason to testify in a way that helps Alan Blizard, his boss, stay out of jail. It goes to bias. Judge: Overruled. The witness may answer. L1: [re-ask the question] Mr. Snyder, if you lost your job at the rink, you’d have to drop out, isn’t that right? Prejudice / Confusion (FRE 403) Otherwise relevant evidence can still be objectionable if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues or misleading the jury, or by considerations of undue delay, waste of time or needless presentation of cumulative evidence. • Response: Your honor, Rule 403 is an extreme remedy where the potential for unfair prejudice [or confusion, if that was the objection] must substantially outweigh the probative value. Given the high probative value of [the evidence/testimony], opposing counsel cannot meet this burden. • Response: The evidence does not present the danger asserted. • Response: The danger asserted does not substantially outweigh the probative value of the evidence. Character/Propensity Evidence (Fed. R. Evid 404-406) “Propensity” arguments are simply arguments suggesting that, since someone has (or hasn’t) done something in the past, it is more (or less) likely that they did it at the time in question. Under the FRE, this is treated as a “character trait.” Think of this as the classic argument, “he must have been speeding since he tends to speed” (or, put another way, “because he has a propensity for speeding” or “because he has the character trait of being a speeder”). FRE 404(a) simply says you can’t use a “trait” (or propensity, or prior actions) as evidence that a particular event occurred (the “action in conformity therewith on a particular occasion”), unless you meet one of the exceptions. FRE 404(b) says you can you crimes, wrongs or acts to show something other than actions in conformity therewith, and gives a list you should consider looking through. FRE 405 says that, when character evidence is allowed, you can prove it through reputation evidence (“everyone in town knows Mr. Smith cheats his employees”) or specific instances of conduct if the trait is an essential element of the charge/claim (e.g., you can use prior speeding tickets to show that its more likely someone was speeding, if “speeding” is an element of the crime, such as the crime of “speeding in a school zone resulting in death of a child”). FRE 406 says that you can show conduct on a particular occasion by showing that the person has a habit or routine of doing that action. For example, if you want to show that someone was in the bathroom at the time of a murder (and, therefore, couldn’t have seen the killer on the other side of the building), you could show that the person has a habit of always brushing their teeth in the bathroom at that exact time of night (say, right after “Golden Girls” ends). • Objection: Impermissible Propensity Evidence. [or] Improper attempt to use character to show action in conformity therewith. • Response: The evidence is not offered for the purpose of proving action in conformity therewith. • Response: Under FRE 404(a), the evidence is admissible as evidence of a pertinent character trait, or offered to rebut the same. • Response: Your honor, we are not offering this to show action in conformity therewith. Under FRE 404(b), the evidence is offered for the purpose of proving [motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, or absence of mistake or accident, as appropriate]. • Response: Under FRE 406, the evidence is admissible as evidence of habit or routine practice. Personal Knowledge/Speculation (FRE 602) The personal knowledge requirement is simply that a witness must have personally seen, heard, or otherwise sensed the event or situation they are testifying about. For example, if the witness was at an intersection and saw the color of the light when an accident occurred, she could testify about the color of the light. But if the witness was in a store during the accident and only later “learned” what color the light was in a conversation, she doesn’t have personal knowledge of the light color. She would have personal knowledge about what the person told her in the conversation, but that is not enough to give her personal knowledge of the light color. “Speculation” and “calls for speculation” are just shorthand objections for a specific type of lack of personal knowledge, where the question obviously calls for the witness to speculate about something they don’t know. For example, asking someone why someone else did something (or what someone else thought, saw, etc.) is almost always asking them to speculate. (Sometimes this is referred to as asking them to “crawl into someone else’s head.”) The correct approach is to ask them what someone said, or indicated, or otherwise communicated about their intentions. • Objection: Lack of Personal Knowledge o Response: This witness has actual personal knowledge of the facts to which he testified. • Objection: Speculation o Response: This witness has actual personal knowledge of the facts to which he testified. Example: L1: Mr. Blizard, did you see anyone when you left the rink? AB: Yes, I saw Adam McKenzie talking on his cell phone. L1: Where was he? L2: Objection, 602, lack of personal knowledge as to Mr. McKenzie’s whereabouts. Judge: Response, counselor? L1: Your honor, Mr. Blizard just testified that he saw Mr. McKenzie. This shows that he has personal knowledge as to Mr. McKenzie’s whereabouts at that time. Judge: Overruled. You may continue questioning. Hearsay (FRE 801-807) “Hearsay” is an out of court statement offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted by the statement. For example, if the witness testifies that someone said “the light was green when I went through,” and you offer the testimony to show that the light was, in fact, green, that’s hearsay. Also, it doesn’t matter if the witness is the declarent; their prior statements are still hearsay if the statements meet the definition and aren’t excepted. Basically, if someone will testify “she told me xyz,” you need to think of why that’s either not hearsay, or is an exception to the hearsay prohibition. The easiest is probably party opponent (801(d)). This means the person who made the original statement is the opposing party (or an agent, etc.). Any witness, even the opposing party, can be asked about statements the opposing party made. Or, you can argue that you’re not using the statement to show that the statement itself is true. Be careful: the “truth of the matter asserted” is not that the person really made the statement, but that the statement itself was true. Why is this important? Because, if you don’t care whether the statement was true, but only that the person made the statement, then it is not hearsay! For example, if you want to show that someone was angry at someone else, you could use their statement, “that bastard cheated me on this contract!” without regard to showing that the bastard actually cheated anyone. Or, if you want to show that someone lied in the past, you can ask them about a statement you think is contradicted by other evidence. If the objection is hearsay, you respond that you are not offering it for the truth, in fact, you think it is untrue. There are a number of hearsay “exceptions,” some of which are actual exceptions (803 and 804), while others are arguments that something is not, in fact, hearsay (801(d)(1) and (2), or the assertion that you are offering it for another purpose (to show knowledge, bias, the declarent’s state of mind, what the declarent believed, etc). • Objection: Hearsay • Response: The testimony does not concern a statement. • Response: The statement is not offered for the truth of the matter asserted, but for another purpose. • Response: Under FRE 801(d)(1)(A), the statement is exempt from the hearsay rule as the witness’ prior inconsistent statement. • Response: Under FRE 801(d)(1)(B), the statement is exempt from the hearsay rule as the witness’ prior consistent statement offered to rebut a charge of recent fabrication, improper influence or motive. • Response: Under FRE 801(d)(1)(C), the statement is exempt from the hearsay rule as a statement of identification made after perceiving another. • Response: Under FRE 801(d)(2), the statement is exempt from the hearsay rule as an admission by a party-opponent, his agent or coconspirator. • Response: Under FRE 803(1), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a present sense impression, describing an event or condition, made while perceiving the event or condition, or immediately thereafter. • Response: Under FRE 803(2), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as an excited utterance, related to a startling event or condition, made while under the stress or excitement caused by the event or condition. • Response: Under FRE 803(3), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as indicative of the declarant’s then-existing state of mind. • Response: Under FRE 803(4), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a statement made for the purpose of medical diagnosis or treatment. • Response: Under FRE 803(6) and 803(7), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a business record, made at or near the time of the event recorded, by a person with personal knowledge of that event, and kept in the regular course of business. • Response: Under FRE 803(8) and 803(10), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a public record, setting forth the activities of public office, matters observed pursuant to duties imposed by law, or factual findings of government investigations. • Response: Under FRE 803(16), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a statement contained in an ancient document, more than twenty years old or the authenticity of which is established. • Response: Under FRE 803(17), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a statement contained in a generally relied upon market report or other commercial publication. • Response: Under FRE 803(18), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a statement contained in a learned treatise, relied upon by experts. • Response: Under FRE 803(21), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a statement of reputation as to a person’s character. • Response: Under FRE 804(b)(1), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as the former testimony of an unavailable witness. • Response: Under FRE 804(b)(2), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a dying declaration. • Response: Under FRE 804(b)(3), the statement is an exception to the hearsay rule as a statement against interest. • Response: Under FRE 807, the statement is not hearsay because it has equivalent circumstantial guarantees of trustworthiness. • Objection: Double Hearsay • Response: See the above responses, offering one response for each layer of hearsay. Additional Sources • STEVEN GOODE & OLIN GUY WELLBORN III, COURTROOM EVIDENCE HANDBOOK (Thomson West 2006) • THOMAS A. MAUET, TRIALS: STRATEGY, SKILLS AND THE NEW POWERS OF PERSUASION (Aspen Publishers 2004) • THOMAS A. MAUET, TRIAL TECHNIQUES (Aspen Publishers 2007)