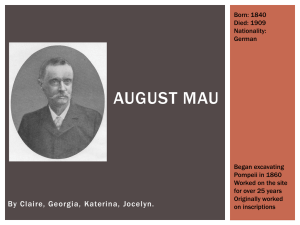

An Insight into Representative Gardens in Roman Wall Painting

advertisement

Purdue University An Insight into Representative Gardens in Roman Wall Painting Jingqi Cong AD 312 Professor David Parrish An Insight into Representative Gardens in Roman Wall Paintings As Gilbert Picard says at the beginning of Roman Painting, the pictorial arts are among the most significant elements in the artistic legacy of Rome if only because of the sheer volume of preserved works (8). This legacy is inherited mainly in a form of fresco wall painting, and we can still see it today chiefly in Herculaneum and Pompeii because of the protective coating formed by the eruption of Vesuvius. If Roman wall paintings are mirrors looking into the society, then the representative garden scenes are components more close to real lives. These artistic heritages provide us with a rare glimpse of aesthetical preference, mentality, and aspiration of the Roman people throughout time. Garden is an abundant scheme. Within a fully decorated version of wall, Romans are able to create an environment combining every imaginable raw material and architectural form. Throughout the history of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire, there are three types of Roman gardens. They are distinguished between palace gardens, villa gardens, and town gardens (Turner 127). Palace gardens are usually located outdoors, and built in great open courtyards with close association with porticoes and colonnades. House of Livia at Primaporta [Fig.1], the villa owned by Augustus`s wife Livia, is a great example of Palace garden. Villas are often seen as symbols of upper-class luxurious refinements. The best surviving example of Villa garden is Hadrian`s Villa at Tivoli [Fig.2], the garden attached to private country house built by Hadrian. Comparatively speaking, town gardens are much smaller and more private in scale. There are many famous peristyle gardens in Pompeii with admirable wall paintings such as the House of the Orchard [Fig.3]. 2 Because of the biological diversity presented in garden paintings, they are always valuable and rare sources of information on the general appearance of domestic Roman gardens. The typical subject of a garden painting was a collection of trees and shrubs against the blue, gold, or russet sky, with birds playing in a gushing fountain at the center of the picture and a fence, or similar barrier, at the base (Stackelberg 30). The most dominated color for garden paintings are usually blue, green, yellow, and black, and most of them were generally earth minerals. The technique here is fresco, although elsewhere, especially in Pompeii, research has shown that paintings were often executed in tempera (Strong 96). Although it is painting on the wall, the notion of depth and perspective is not eliminated at all. To achieve the sense of dimension on the flat surface, the closer subjects in garden paintings are treated in finer detail while the background subjects are painted less sharply. In the later style, even chiaroscuro, the treatment with light and shadow, has been used to create architectural illusion. There are four styles for Roman wall paintings in a chronological order. The garden paintings started to boom at the early Second Style illusionism. The first, and finest example is the so-called Garden Room in the Villa of Livia at Primaporta[Fig.1]. Built and decorated some time round 20 B.C.E., this partially subterranean chamber, nearly 12m long and nearly 6m wide, was turned entirely into a kind of open-sided pavilion set in a paradise forest (Ling 150). Although there is no great vista of depth being demonstrated, the vivid color and accurate representation of individual species still establish the painting`s remarkable value in history of art. The only architectural element in the painting is the flimsy fence of the garden 3 itself. The precisely painted fence, the birds and fruits on the trees, along with blurrily treated background subjects, help create an impressive atmosphere. Villa of Livia is an Anthem for the nature. Departing from the Second Style realistic nature, not only a new form of visual image has been developed, but also the totally changed mentality has led to a new domestic decorative style. Decorations become the distinctive characteristic for Third Style wall painting. House of Orchard from Pompeii[Fig.3] is a great example of extravagant Third Style garden painting. With trees and shrubs standing out negatively on a luxury black background, the representation becomes less realistic. Unlike Livia`s Second Style, the wall divided into three distinct panels by golden linear ornament, and each zone has an independent content. The garden painting is located within the interior of the house to give the impression of looking out of a window on to a garden. Also, the three-dimensional effect becomes more intense with the shadow on the fence. Different from the decorative scenes, there is another kind of garden painting emerging within the Third Style called “sacral-idyllic” landscape. The Villa of Agrippa Postumus from Boscotrecase[Fig.4] is one of the best examples. The garden painting is assigned into a balanced proportion with narrow but elegant lines. A shepherd and his goats are wandering in a rustic background. The clear delineation of wall, ornament, and a uniform color scheme in the individual rooms betokens a new longing for calm, order, and clarity (Zanker 283). Other than pompous atmosphere, everything in this garden painting seems so peaceful. Indeed, the Third Style is probably the most successful Roman style of interior decoration. 4 Other than the aesthetic value Roman ancestors have left us, representative garden paintings have many actual functions both in the past and now in archaeological research. According to the research of Jashemski, the Pompeians put their gardens in the middle of their house, instead of putting their house in the middle of their garden as we do. Therefore, the space of the garden is usually very limited. One of the most popular roles of garden paintings for Pompeians is as a means of enlarging the space in their actual garden. The charming practice of making a small garden larger by painting trees and flowers on one or more of the garden walls was a common one at Pompeii and other Vesuvian sites (104). With this strategy, flowers that have no seed to grow and trees that are too large to plant can be easily enjoyed in domestic gardens. For archaeologists, these garden paintings are extremely important source of information about ancient Roman plants, animals, and even climates. They study and identify the plants in the painting, and compare them with the plants that grow in the area today (Jashemski 105). Roman garden painting not only provides us an abundant horticultural and biodiversity resource, it also gives us some insight into Roman cultural practices, their social values, and most importantly ancient Roman`s profound love and admiration for nature. From the illusion of delightful gardenscapes, one of the most important Roman key concepts about life “Otium” is being revealed. “Otium” is a Latin abstract term, which means private world of leisure. With the imperial expansion in the late Roman Republican era, more and more husbandmen and peasants become wealthier than before. Therefore, they start to build private houses and pursue peaceful leisure. By cherishing “Otium”, one could escape 5 into this realm from the chaos of the civil war and the suffering of the Republic in its death throes, and in it one could seek new avenues to self-fulfillment (Zanker 31). The garden paintings can actually date back to some Literature content. The Georgics is a poem written by the Latin poet Virgil. In this poem, the author celebrates the peaceful life and piety, and expresses his wish to escape from the chaos. He highly praises the abundant land and nature by saying: A breach, and deep into the solid grain A path with wedges cloven; then fruitful slips Are set herein, and- no long time- behold! To heaven upshot with teeming boughs, the tree Strange leaves admires and fruitage not its own (Virgil). I think the exactly same message of pursuing the notion of “Otium” is conveying from Roman garden paintings. Roman people use garden paintings as a vehicle of cultural communication, thus promote their power, awe, and pleasure towards nature to whoever appreciates them. 6 Reference Jashemski, Wilhelmina F. The gardens of Pompeii, Herculaneum and the villas destroyed by Vesuvius. Caratzas Brothers, 1979. Katharine, T. The Roman garden: space, sense, and society. Routledge, 2009. Ling, Roger. Roman painting. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991. Picard, G. Roman painting. New York: Elek Books, 1970. Strong, Donald Emrys, and Jocelyn MC Toynbee. Roman art. Vol. 44. Yale University Press, 1995. Turner, Tom. European gardens: history, philosophy and design. Routledge, 2011. Zanker, Paul. The power of images in the age of Augustus. University of Michigan Press, 1990. 7 Figure.1 The Villa of Livia, Primaporta, ca. 30-20 BEC. Figure.2 Hadrian`s Villa, Tivoli, ca. 125-128 Figure.3 House of Fruit Orchard, Pompeii, ca.40-50 8 Figure.4 Villa of Agrippa Postumus, Boscotrecase, ca. 10 BCE 9