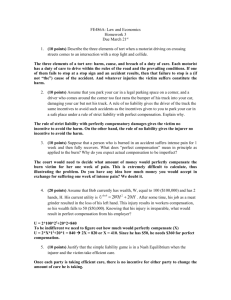

1 MISALIGNMENTS IN TORT LAW Ariel Porat* In negligence law

advertisement