Exploring the UK Freelance Workforce, 2011

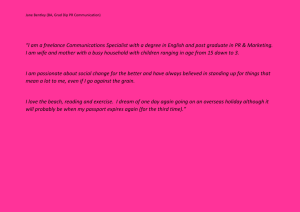

advertisement