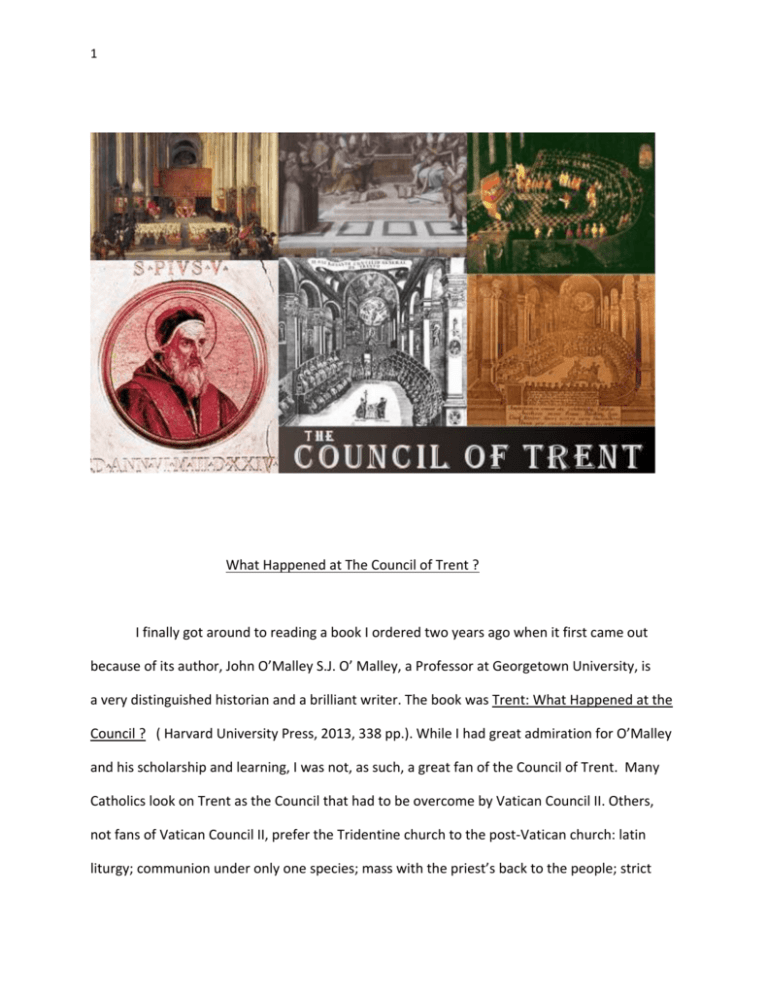

What Happened at The Council of Trent

advertisement

1 What Happened at The Council of Trent ? I finally got around to reading a book I ordered two years ago when it first came out because of its author, John O’Malley S.J. O’ Malley, a Professor at Georgetown University, is a very distinguished historian and a brilliant writer. The book was Trent: What Happened at the Council ? ( Harvard University Press, 2013, 338 pp.). While I had great admiration for O’Malley and his scholarship and learning, I was not, as such, a great fan of the Council of Trent. Many Catholics look on Trent as the Council that had to be overcome by Vatican Council II. Others, not fans of Vatican Council II, prefer the Tridentine church to the post-Vatican church: latin liturgy; communion under only one species; mass with the priest’s back to the people; strict 2 rules; papal centralization of authority, with bishops as kind of lackeys to the pope. As a seminarian studying theology I had read and studied the various decrees of Trent on justification, original sin and the seven sacraments but had no real sense of the power-plays, limitations and possibilities of what could be done in Trent. I certainly did not know that the reform party at Trent wanted mass in the vernacular, communion under both species, a stronger sense of bishops as having their mandate from God and not just from the pope, a relaxation of the celibacy rule to allow married priests. Like many I saw Trent as just a reaction to Luther and Calvin in a kind of Counter-Reformation which was not an adequate true reform. O’ Malley situates for us the principal actors at Trent. Three popes were involved in the long period covering the council’s three periods, 1545-1547; a long middle period of suspension of the council and some brief gatherings, 1547-1562; and the final session of the Council, 156263. The Popes were Paul III, Julius III and Pius IV. By and large the popes were somewhat fearful of the Council, afraid it might question papal authority vis a vis a council or call for major reforms of the College of Cardinals. The Popes were open to discussion about doctrines denied by the Protestant Reformers: the role of human agency and grace; the meaning of original sin; the Reformers’ denial of the legitimacy of papacy or episcopacy; their denial of there being seven sacraments and their refusal to accept parts of the bible which in the Catholic bible derived from the Greek translations from the Septuagint which Luther saw as not really part of the authoritative bible—the so-called apocryphal books of the bible. Other actors at Trent included many political actors. As O’Malley notes the Council was as much a political as a theological and ecclesiastical story. Charles V and, later, Ferdinand, the Holy Roman emperors, wanted deep reform of the church as a way of addressing the rise of Luther and Calvin in German held lands. The French kings, Francis I and Henry III, were not keen 3 on a council controlled by Charles V and Ferdinand and held at Trent ( in Habsburg held territory). The French kings also were at times enemies of the popes and in a war between French troops and the papal states had won, in 1515, a concord with the pope which allowed the French kings to control the nominations for bishops in France. But some elements in France ( the bishops, the faculty of The University of Paris) hoped the Council would remand this condordat. So, the French kings were not in favor of a council. Moreover, given some Gallican tendencies, they wanted to hold their own council, controlled by them, in France. The Spanish king, Philip II, like the French kings ( and the Holy Roman Emperors and the Portuguese kings), had the right to control the nominations of bishops in his territories. But reform was strong on the agenda of the Spanish kings and, indeed, under the leadership of Archbishop Cisneros of Spain, reform had taken deep roots in Spain, even before Trent. Charles V and later Ferdinand were avid for widespread reforms in the church to address Luther and Calvin. They opted for a vernacular liturgy, communion under both species, the relaxation of mandatory celibacy for priests ( German bishops claimed that in some areas, for every hundred priests, only three or four practiced celibacy, the rest lived in open concubinage , much to the scandal of the laity ). The Germans also wanted to invite the Reformers to the Council in a hope ( probably vain) of reconciliation with them and the Catholic Church ( such gatherings which did occur did not eventuate in any such reconciliation). Besides the political figures and their legates, there were also superiors of mendicant religious orders with voting rights and a large group of theologians ( whose nomination or numbers was not controlled by the Popes). Lurking behind all discussions at the Council was the vexed questions of the reform of bishops. Many dioceses had absent bishops. Many bishops held multiple sees. But the Popes feared ( remember in an earlier century the Council of Constance which deposed the three competing popes) the question of the relationship of the 4 Pope to the Council ( was it only at his bidding or did it have an authority even over the pope ?) and the other question of the authority of bishops ( were they merely derivative from the Pope or was their authority, jure divino, directly from Christ?). The popes wanted the council only or mainly to address doctrinal issues. The Holy Roman Emperors, French Kings and Phillip II of Spain wanted more emphasis on reform of the church. Papal delegates ( called zelanti) were chary of too much emphasis on reform. At no time were a majority of bishops present at the Council. Of the 700 bishops in Catholicism, except for the third session of Trent, less than a hundred attended. At the first session the Council took up the issue of “ The Sacred Books and Apostolic Traditions”. It accepted the so-called apocrypha from the Greek Septuagint but did leave open a bit the dispute about their authenticity. Luther denied them but so had Saint Jerome. Augustine accepted them. Many fathers at the Council felt it would be mistaken to come down too heavily on a question disputed by the early Fathers of the Church themselves. So, with the earlier Council of Florence, Trent accepted the apocrypha in its listing of the books but did not enter fully into the disputed question of their full authority as scripture. Another issue was the question of vernacular translations of the bible. These were not allowed in France or Spain but allowed in Germany, Italy and Poland. The Council left the question of vernacular translations open ( even allowing Catholics to read translations of the bible done by heretics). On the question of the relation of scripture and tradition, the Council allowed a role for unwritten traditions “ that were received by the apostles from the mouth of Christ or came down to us from the apostles operative in an unbroken sequence.”. After the Council, Pope Pius IV’s Tridentine Profession of Faith ( promulgated in 1564) was less subtle or careful in its wording than Trent in dealing with church tradition as a source of authority. The Holy Roman Emperor wanted mass in the vernacular; a renewed catechism; 5 seminaries for the training of priests; the mitigation of the rule of celibacy for priests; communion under both species; an index of recommended rather than forbidden books. The Council did mandate seminaries to train priests. It thought that such good training would mitigate any need to relax the rule on celibacy for priests. Right after the Council a new catechism was issued under Pius V ( 1566). At the Council there were divisions on the question of mass in the vernacular and communion under both species—the Italians and Spanish against and the Germans in favor. The Council left those questions to the discretion of the Pope who, in fact, allowed vernacular liturgies and communion under both species in the German lands. But after some seventy years, even in the German lands these were abandoned. The main reforms at Trent were decrees that demanded bishops and priests be resident in their dioceses or parishes and doing away with multiple benefices for bishops and priests. Another important reform was the need to have seminaries to train priests. A third reform dealt with clandestine marriages. The Tridentine decree, Tametsi, now demanded for the first time that Catholics had to be married with a priest witness. Doctrinally, Trent did a major document on justification ( we are saved by faith and the grace of God, not by our works—but humans do retain a kind of freedom to accept God’s grace and respond in faith or not). There were also documents dealing with the seven sacraments and the eucharist as a sacrifice. Toward the end of the Council, the Council issued decrees on purgatory, indulgences, fasting and the veneration of saints’ images and relics—but these were rushed with little real time for careful discussion. Catholicism, after the Council, was more sacramental than ever. More Catholics received communion more regularly. Confessionals were introduced into the churches. The canard, however, that Protestants got the word and Catholics the sacraments is not true. Catholic preaching flourished more after the Council because of residential bishops and priests 6 who were urged to preach regularly. The Council insisted in two places that preaching was the principal duty of the bishop. To some extent, however, reforms made after Trent ( which included a greater centralization of authority in Rome) helped to bolster a myth about Trent as much as the documents of the Council itself. It was a kind of miracle that the Council was ever held and that some of the reforms it enacted did address a real reform of the church. But it took another four hundred years for another Council, Vatican II, to address some of the issues first broached at Trent. O’ Malley’s book is certainly well worth reading.