Using Search Time and Regression to Estimate

advertisement

Using Search Time and Regression to Estimate Abundance of Territorial Spotted Owls

Author(s): James P. Ward, Jr., Alan B. Franklin, R. J. Gutierrez

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Ecological Applications, Vol. 1, No. 2 (May, 1991), pp. 207-214

Published by: Ecological Society of America

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1941813 .

Accessed: 15/03/2012 13:30

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Ecological Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Ecological Applications.

http://www.jstor.org

Ecological Applications,1(2), 1991, pp. 207-214

? 1991bytheEcological

SocietyofAmerica

USING SEARCH TIME AND REGRESSION TO ESTIMATE

ABUNDANCE OF TERRITORIAL SPOTTED OWLS'

JAMESP. WARD, JR., ALANB. FRANKLIN,

ANDR. J.GutiuRREz

Department

of Wildlife,

Humboldt

StateUniversity,

Arcata,California

95521 USA

Abstract. Usingconventional

samplingmethods,unbiased,preciseestimatesof the

numberofindividualsin a populationcan be difficult

to obtainforrare,secretive

species.

We used a Leslieregression

model(LRM) to estimatethenumber(No)and thevariance

ofthenumber(V[No])ofadultand subadultNorthern

SpottedOwls in a territorial

populationfromdirectcountswithina 292 km2 studyarea.EstimatesofNofromdaycounts

weremoreaccurateand preciseand morerobustto fluctuations

in surveyeffort

than

estimates

fromnight

counts.LRM estimates

fromdaycountswerenotsignificantly

different

fromtwodifferent

maximum-likelihood

estimates

and required30-64%lesseffort.

These

findings

suggesta less costlymethodforstatistically

comparing

SpottedOwl abundance

betweenspatialor temporalunits.

Keywords: abundance;

callsurvey;

Leslieregression

model;maximum

likelihood

estimator;

NorthernSpottedOwl;population

occidentalis

size; Strix

territorial.

caurina;

owl are poorlyunderstood(Dawson et al. 1987). A

pointforunderstanding

viabilityof

The numberofindividualsalive in a populationat logicalstarting

a giventime(N,)is a fundamental

parameter

ofmany SpottedOwl populationswouldbe to modeltheexecologicalstudies.Methodsofestimating

size of ani- istingpopulation,whichwouldrequirean abilityto

N. Anyreasonablecomparison

mal populationsare well documentedand thorough estimateand monitor

of

over

time

or

between

habitatswouldalso require

N,

reviewscanbe foundin Caughley

(1977),Seber(1982,

varianceassociatedwithNt.

1986),and Krebs(1989). However,unbiasedandpre- a measureofthesampling

nocturnal

that

predators

cise estimatesof (N,) usingconventionalsampling SpottedOwlsareterritorial,

live in old-growth

coniferforests

ofthePamethodsmaybe difficult

to obtainforsome species primarily

(Solis 1983,Forsmanet al. 1984).Be(e.g.,Burnham

etal. 1980,Reynoldsetal. 1980,White cificNorthwest

anduselarge(400-1800

etal. 1982)becausesampling

assumptions

aredifficultcausetheseowlsareterritorial

low

to meetand estimators

arenotrobustto violationsof ha) tractsofhabitat,populationsattainrelatively

assumptions.

Specifically,

speciesthatuse largeareas, densities(Forsmanet al. 1984,Franklinet al. 1990).

occurin lowdensities,

or aredifficult

to observe(e.g., The owl's nocturnalhabitand low density,coupled

prohibit

use oflinetransect

largepredators,

nocturnal

or secretive

species)cannot withsteep,ruggedterrain

et al. 1980),or variableplot(Reynoldset

be sampledadequately

without

tremendous

fieldeffort. (Burmham

theirabundance.

it is thelargeor rarepredators

Ironically,

thatmay al. 1980) methodsforestimating

However,

March

during

through

August

bothmembers

be promotedas "umbrella"(Peterson1988), "keydefenda breeding

territory

using

stone"(Norton1988),or "indicator"(Salwasseret al. ofan owlpairactively

(Forsmanet al. 1984). Young

1982,Salwasser1988) speciesin an effort

to preserve vocal advertisements

For example,in thePacificNorthwest, dependon theirparentsuntildispersaland do notdebiodiversity.

in thefall(Gutierrez

beforedispersing

ofNorthern

maintenance

SpottedOwl (Strixocciden- fenda territory

taliscaurina)populations

is promoted

as a waytocon- et al. 1985). Aftertheirjuvenilemolt,subadultowls

byplumagecharacters,

serve old-growth

coniferousforests(Thomas et al. (1-2 yrold) can be recognized

1988). Proposedplansto maintainviableowl popu- and thesebirdsmay obtainand defenda territory.

adult,andsubadultSpottedOwlscan

lationsconsistof a network

of suitablehabitatareas Thus,territorial,

theircallsandelicbyimitating

(UnitedStatesForestService1988).Thesizeandstruc- be locatedconsistently

during

thebreeding

period(Forstureofthoseareasneededto maintainowloccupancy itinga vocalresponse

are becomingwelldocumented

(Solis 1983,Forsman man 1983).

We infer

frombandingstudiesthatSpottedOwlsare

et al. 1984, Ganeyand Balda 1988, 1989, LaHaye

1988,Laymon1988,Bias 1989,Careyetal. 1990,Sisco longlived and have high(0.96) annualadultsurvietal., unpublished

data).Mor1990).However,thearrangement

andnumberofhab- vorship(A. B. Franklin

in thenonadultsoccursprimarily

itatareasneededto maintainviablepopulations

ofthe talityin territorial

INTRODUCrION

breeding period (A. B. Franklin et al., personal

1 Manuscript

received22

cepted23 July1990.

January1990; revisedand ac-

Weoccasionally

birds

observation).

encounter

unbanded

duringnighttime

callingsurveysthatwe cannotrelo-

208

JAMES P. WARD, JR. ET AL.

EcologicalApplications

Vol. 1. No. 2

cateduring

theday.Sincetheseowlsareusuallywithin Foreachyear,thetime(inminutes)

devotedbyeach

to callingfor,searching

for,andlocatingowls

of a markedpair,we believethatthese observer

theterritory

We wasrecorded

separately

fornighttime

anddaytime

surmembers

ofthepopulation.

birdsarenonterritorial

willbe referred

and ecologyofnon- veysand,hereafter,

to as surveyeffort.

knowlittleaboutthedemography

did notincludetraveltimebetweencall

territorial

birds.We also do notknowaboutthenight- Surveyeffort

orsurvey

noranyadditionalfieldeffort.

birds.However, stations

timeresponserateof nonterritorial

routes,

withingeographic

thenumberofbandedbirdsdetectedwhilespot-light- Surveyswereconducted

subunits

owlsat day roostsin- ofthestudyarea.Subunitsweredelineated

ingowlsat nightor observing

byobservbirds(bothadultand sub- ers usingtopographic

and habitatfeatures,

dicatesthatnonterritorial

and reppotential

owlterritories.

home resented

haveunstable

Theseterritories

often

were

adults)do notcallfrequently,

throughoutused to assignsurveyeffort

observable

to the numberof owls

ranges,

andarenotconsistently

ofbanded counted.Oncea pairofowlswaslocatedin a territory,

a shorttimeperiod.Thus,ourobservations

birdsal- additionalowl responsesand additionalsurveyeffort

birdsindicatethatwe are locatingterritorial

or withintheterritory

mostexclusively

andthatthereis littleimmigration

wereignored.Ifonlya singlebird

emigration,

and fewbirths(e.g.,juvenileowlsare not was detectedin a territory,

additionaleffort

was dedur- votedto locatinga potentialmateuntila matewas

locatedbycalls)ordeathsin thestudypopulation

ing the censusperiod.These conditionsallow us to countedor theannualcensusended.If an area conofcatch- tainedmorethanone pair,thenumberof territories

meetsomeofthebasicbiologicalassumptions

and surveyeffort

withineach area wereadjustedaceffort

methods(Seber1982:296,Krebs1989:162).

In thispaper,weusea Leslieregression

model(LRM; cordingly.

Thus,weusedtheassociationofan owlwith

abundanceandthe a giventerritory

to inferowl identity

Leslieand Davis 1939)to estimate

and theamount

varianceof abundanceof SpottedOwls fromdirect of time necessaryto locate an individualwithout

counts.We also compareLRM estimatesbased on knowledgeof bandingrecords.Concurrently,

we atbasedon day- tempted

to captureand markall individuals

nighttime

countsofowlswithestimates

withcolofthismethodby oredleg bandsto confirm

timecounts,andevaluatetheutility

and evaluatethis

identity

LRM estimateswithtwomaximumlike- assumption

(Franklinet al. 1990).Effort

comparing

requiredfor

was also recorded.

(Zippin1956,Jolly1965,Seber1965, marking

lihoodestimates

Whiteetal. 1982).Thismethodmaybe applicablefor

Leslie regressionmodel (LRAM)development

abundanceofotherspeciesthatbehavesimestimating

Call surveys

provideda directcountwithout

a meailarlyto theSpottedOwl.

sureof precision.An LRM (Leslie and Davis 1939)

METHODS

was used to estimatethenumberof adultsand subadultsalive at thebeginning

Studyarea

of each breedingseason

and

a

95%

confidence

interval

forNo.

(NO),

Adultand subadultNorthernSpottedOwls were

modeland works

countedin a 292.4 km2 studyareanearWillowCreek, The LRM is a closed-population

withinthisstudyareawas on thetenetthatthenumberofindividualsremoved

USA. Vegetation

California,

or Klamath by samplingfroma givenarea willdeclineovertime

forest

classified

as eithermixedevergreen

montaneforest

(Kiichler1977),andhasbeendescribed (Leslieand Davis 1939,Seber1982:296,Krebs1989:

lineoftheform

in detailelsewhere

(Solis 1983,Franklinet al. 1990). 162).Thus,a regression

43% ofthestudyareawas considered

Approximately

(1)

Y,= a + bX,

et al. 1990).

suitableSpottedOwl habitat(Franklin

elevationsand slopes can be fitto thenumberof individualscapturedper

Terrainwas steepand rugged;

(Y1),and thecumulativenumberof inranged from 150 to 1700 m and from 18? to 550, re- unitof effort

dividuals

captured

priorto eachsurveyintervali (Xi),

Studyarea boundariesweredrawnalong

spectively.

a

least

using

squares

analysis(Zar 1984:263-265).Folto minimizeoverlap

features

prominent

topographical

lowing

the

notation

of

Seber(1982:296),and usingthe

betweenthestudyareaand adjacent

ofowl territories

slope of theregression

line (b) as an estimateof the

habitat(Franklinet al. 1990).

coefficient

ofcatchability

(K), No can be calculatedas

Owlsurveys

(2)

No =X+ (Y/K).

Owls werelocatedand countedusingvocal imitationsofthespecies'callsduringsurveysat night(1/2

h The intercept

ofthex axis bytheregression

linealso

h priortodawn)andduring

theday, providesa pointestimateofNo (Seber1982:298).

priortoduskto 1/2

August,1985 to 1987 (Forsman1983,

Aprilthrough

The varianceof No,or V[NO],can be estimatedas

Franklin

etal. 1990).Nightsurveys

wereconducted

at follows:

callstations

were

established

alongroadsand,generally,

usedto locateand countowls.Day surveysconsisted

2i 1

(N- X)2]

ofmoreextensive

wereused

searchesand,specifically,

tolocateandcountowlsbyvisualobservation

atroosts.

=

May 1991

ESTIMATING OWL ABUNDANCE

where12 is themeansquareerrorfromtheleastsquares

samplesize(Seber1982:

analysisands is theregression

from

interval

canbe estimated

298).A 95%confidence

V[NO]usingthedeltamethodwhens is large(> 10),

No ? 1.96(/N01])/2,

209

DAY-1985

o

70 -~f213"

70-

(4)

C

o) 501

or by usingtheproceduredescribedby Seber(1982:

tm h 11

n.

299) whens is small.

ourvocalimitations

To usetheLRM, weconsidered

as "bait" to enticeowls to respond.Owls thatwere Z 30w

I

detected,eitherby sightor sound,wereconsidered

as

"captured."We calculatedcatchperuniteffort,

Yi,

thenumberofowlsdetected(n,)dividedbytheasso10

ciatednumberofhoursofsurveyeffort

(f),in eachof

s sampling

periods.The latterwerecreatedbysystem250

100

150

200

50

0

surveyresultsfroma givenyearwith

aticallygrouping

CUMULATIVEHOURS SURVEYED

an arbitrary

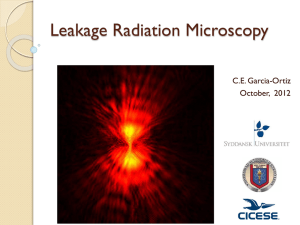

windowof time,m hourslong(Fig. 1).

becausetheamount FIG. 1. Procedureforgrouping

Groupingof data was necessary

SpottedOwl call survey

model,wherem is the

of effort

devotedand the numberof owl territoriesdataforinputintoa Leslieregression

in

(time)interval,

niis thenumberofowlsdetected

sampledduringanygivensurveyweresmallrelative grouping

timegroupi, andf is thetimein hoursrequiredto locate

to totalsurveyeffort

(Fi) and thetotalnumberofowl and countn,

Without

territories

sampledeach year,respectively.

thedata over time,too fewowl territories

grouping

werequantified

wouldhave been sampledand the numbersof owls inputintotheLRM. Theabovecriteria

detectedduringeach sampling

periodwouldnothave and evaluatedusinga chi-squaregoodness-of-fit

test,

declinedthrough

time,a requisiteforusingtheLRM. a Student'st test,and thestandarderroroftheregresthe cumulativenumberof sion dividedby Y, respectively.

For example,grouping

Statistical

testswere

devoted deemedsignificant

owls detectedforeverym = 23 h of effort

at the5% level(a = .05). A BASIC

in 1985givesY1= 0.708 owls computer

was developedto keepthisproceprogram

duringdaytimesurveys

detectedperhourand X1wouldequal 0 owlsdetected durestandardized

amongdata setsand users.

Becausethe

periodI (Appendix).

previousto sampling

LRM estimates

ofNowerecomparedto (1) theminLRM imumnumberofindividualsknownto be alive (Nm)

selectionof m mighthave influenced

arbitrary

werecalculated based on markingresults(Franklinet al. 1990), (2)

X and Y valuesforall surveys

results,

every maximumlikelihoodestimatescalculatedusingthe

1) h, incremented

byvaryingm from2 to (F1/1

1 h. The latterterminus

was usedto ensurethatcon- generalizedremovalmodel (Mbh) of programCAPfidenceintervalswerecalculatedusings > 10 (Seber TURE (Zippin 1956, Otis et al. 1978, Whiteet al.

modelD estimatesfrom

1982),and (3) Jolly-Seber,

1982:12,Krebs1989:164).

JOLLY(Jolly1965,Seber1965,1982,FrankThedatasetthatbestadheredtomodelassumptions program

was selectedforestimating

No,foreach surveytype, lin et al. 1990).

owls

surveys

represented

The n,talliedfromdaytime

oftheLeslie

foreachyear.Therearethreeassumptions

and demo- foundat a roost.Becausedaytimeroostsofindividual

method:thepopulationis geographically

fromroostsinadjacentowl

ofan individualbe- owlswerespatially

distinct

closed;theprobability

graphically

owlscouldbe countedand effecroosting

throughoutterritories,

Pi) is constant

ingcaptured(i.e.,detected;

are equal tively"removed"fromthepopulation.Hence,then,

and detection

theexperiment;

probabilities

datathatbestfitmodelassumptions

inthepopulation

(Krebs1989).De- fromthedaytime

amongindividuals

can be consideredconstantand weretreatedas removaldataand inputintotheCAPtectionprobabilities

estimateswereindeequal ifsamplingis a Poissonprocesswithrespectto TURE Mbhmodel.Jolly-Seber

results

effort(Seber 1982:296). The generalizedremoval pendentlycalculatedfrommark-recapture

et al. 1990).

method(Whiteet al. 1982:109)also can be used to (Franklin

ofvariationforNo werecalculatedas:

Coefficients

evaluateconstancyand equalityof pi. Thereare no

simpletestsforpopulationclosure(Whiteetal. 1982:

(5)

cv(NO)= {[V(No)]'2/NN}x 100.

are valid thedata

162). However,ifall assumptions

willfita straight

line and thevarianceaboutthere- Expectedestimatesof No thatdeviatefromtruepagressionlinewillbe constant(Krebs 1989:162-164). rametervaluesare biased.Becausewe did notknow

Thus,datathat(1) providednimostlikelydistributed thetruepopulationsize we couldnotestimatestatisas a Poisson,(2) resultedin a regression

slope least ticalbias. However,we couldevaluateeachestimator

numrelativetotheminimum

estimates

likelyto equal0, and (3) providedthelowestvariance bycomparing

wereused as berofowlsknowntobe alive,Nm,usingthecalculation:

of observedvaluesabouttheregression

ni

0

JAMES P. WARD, JR. ET AL.

210

EcologicalApplications

Vol. 1,No. 2

1. Surveyeffort

devotedto locating,

and recapturing

marking,

Northern

SpottedOwls,Aprilthrough

August,1985

to 1987,nearWillowCreek,California.

TABLE

Hoursofeffort

Year

1985

1986

1987

Nightsurvey

%*

h

208.5

95.5

122.1

31.0

12.8

10.7

Day survey

%*

h

266.3

199.4

286.6

39.5

26.6

25.0

Mark-recapture

%*

h

Total

survey

al

recapture

No.

owlst

198.8

453.3

474.8

294.9

673.6

748.2

65

65

736.3

29.5

60.6

64.3

736.3

1145.0

67

* Percent

oftotalhoursdevotedto surveyand mark-recapture

effort.

knownto be alivein a 292.4 km2areabasedon bandingdata.

t Numberofadultand subadultindividuals

[(No- Nm)/Nm]x 100. Negativeresultswould indicate (1987 nightLRM, P < .05; all otherLRMs,P < .001;

rangedfrom

ofNo.Costs Fig.2). Standarderrorsofall regressions

thattheLRM providedan underestimate

modelD estimates 29 to 68% ofthemeanYvalue fromeachsurveytype.

to produceLRM and Jolly-Seber

detection

ofconstant

and the Thus,theassumption

probability

of surveyeffort,

wereconsidereda function

All

regressions.

re- was violatedfor4 ofthe6 bestfitting

effort,

and mark-recapture

sum of surveyeffort

otherassumptions

appearedvalid forselectedregresspectively.

removalmethod

sionmodels.Additionally,

thegeneral

RESULTS

ofprogramCAPTURE testedforand selectedan esAnnualdirectcountsofadultand subadultSpotted timatorofNo assumingequal detectionprobabilities

during1985 to 1987,even fordaysurveydata collectedin 1985and 1986.Nine

Owls variedonlyslightly

wereassumedin esthrough different

detectionprobabilities

fluctuated

thoughnightand daysurveyeffort

time(Table 1). On average91% of theowlscounted timating

No fromdiurnalcountstalliedin 1987.

withinthestudyarea eachyearwerebandedafterdePopulationestimates

tection.

Estimates

ofthenumberofterritorial

adultandsubTests of assumptions

adultSpottedOwls in thestudyarea variedwiththe

testsfrom methodof estimation

limitscalforthePoissongoodness-of-fit

(Fig. 3). Confidence

Probabilities

bynightsur- culatedusingtheprocedure

data setsgenerated

forsmallsamplesizes(i.e.,

thethreebestfitting

Seber1982:299)wereasymmetveyswere,P < .25,.001,and.001during1985through a quadraticformula;

andP < .001,.10,and .001 forday rical,and upperlimitswereconsistently

greater

than

1987,respectively,

>0 confidence

Allregression

lineslopesweresignificantly

limitscalculatedusingthe delta method

surveys.

intervals

for1985 nightand day sur(e.g.,confidence

veyswere71-692 and 51-71,respectively).

The delta

method

was

used

to

evaluate

differences

among

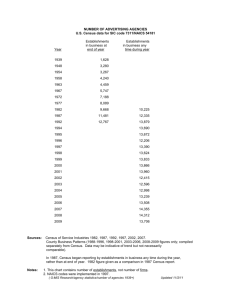

estibetween directcounts and esTABLE 2. Percentdifference

matorsbecause(1) theupperlimitcalculatedfor1985

timatesof the numberof territorialSpottedOwls (No) in a

292.4 kM2 stuidyarea near Willow Creek, Califomia, and night-based

estimates

usingthequadraticformula

apprecisionof N,

pearedbiologically

unrealistic,

(2) all sampleswere> 10

(Seber1982:12,Krebs1989:164),and (3) Noappeared

Percent

cv[No]

to be normally

distributed

(Seber1982:12).

difference (%)

Model*

nt

Year

LRM estimates

ofNobasedonnightsurveys

differed

+70.7

34.5

19

1985

NightLRM11

< .05) fromLRM estimates

significantly

(P

based

on

12

-10.8

6.9

Day LRM23

in

and

from

maximum

day

surveys

1986,

likelihood

12

-6.2

7.5

Day CAP.Mbh

in 1986and 1987(Fig.3). Duringthe1styr

4.7

estimates

0

Jol-SebD

in an overestimate

ofsampling,

resulted

nightsurveys

14

9.8

-20.0

1986

NightLRM7

17

7.8

+7.7

Day LRM12

of Nmby as muchas 71%, whereasnightsurveysin

17

+13.8

9.8

Day CAP.Mbh

Nm(Table2). Annual

subsequent

yearsunderestimated

+7.7

2.6

Jol-SebD

LRM estimatesbased on nightsurveysappearedto

12

-9.0

9.2

1987

NightLRM1

fluctuate

withannualsurveyeffort.

proportionally

12

+6.0

7.0

Day LRM24

In

contrast,

LRM

estimates

based on day surveys

12

+1.5

4.9

Day CAP.Mbh

2.6

+13.4

Jol-SebD

weregenerally

consistent,

withtheexception

ofthe1st

by 11% (Table 2).

* LRM = Leslie regression model, CAP.Mbh= Program yrwhenNmwas underestimated

CAPTURE removal model, Jol-Seb= Jolly-Sebermodel D;

LRM estimates

ofNobasedon daysurveys

wereequal

subscriptsrepresenttheinterval,m hourswide,used to group to or lessthanmaximum-likelihood

on 3 of

estimates

the data priorto model input.

6

All

occasions.

but

the

estimates

1985

night-based

t LRM n = numberofx, y coordinates;CAP.Mbh= number

wereprecise(cv[NO]< 10%;Table 2). LRM estimates

of samplingsessions.

May 1991

ESTIMATING OWL ABUNDANCE

NIGHT SURVEYS 1985

Y 0.741 - 0.007X

3-

211

DAY SURVEYS 1985

Y- 0.612 - 0.OO IX

1.5

21

0

Li..

1

.5 -

*

0

t

CL

w

0

20

60

80

NIGHT SURV/EYS1986

Y:I.1823 -0.036 X

3

tk

40

2

-

20

1.5 *Y:~0.735

a:

oH

0

40

60

80

DAY SURVEYS 1986

-.0.010OX

1\

.

35

U

03

U

0*0

I-.

0

0

U

20

60

80

NIGHT SURVEYS 1987

Y- 1.132-0.019X

X

3

z

40

20

60

40

80

DAY SURVEYS 1987

Y 0.551 -0.008X

1.5

2

1

O '_

0

0

0

.5

20

*

g

40

55033

60

80

U

0

20

40

60

80

OWLS PREVIOUSLY DETECTED

ofthenumberofindividualSpottedOwlsdetectedperhourofsurveyeffort

FIG. 2. Regression

againstthecumulative

withina 292.4 km2areanearWillow

detectedduringnighttime

and daytimesurveys

numberofindividualowlspreviously

Creek,Califomia,1985 to 1987.

based on day surveyswere less precisethan the JollySeber estimatesbut more precise than the LRM estimatesbased on nightsurveysduringall years,and more

precise than the general removal model of program

CAPTURE during1985 and 1986.

LRM estimatescost 30-64% less than mark-recapture estimates, considering the additional time required to markand capturethe birds (Table 1). More

timewas devoted to mark-recaptureactivitiesin 1986

and 1987 to marktrap-shyowls withcolor bands. Resightingowls, ratherthan physicallyrecapturingowls,

in subsequentyearsbutat least

would requireless effort

owls,becausethe

thanonlycounting

30% moreeffort

used to lureowlscloseenoughto

and methodseffort

colorbandsare similarto thoseusedforcapidentify

birds,as was thecase in

unmarked

turingpreviously

however,is thefact

1985 (Table 1). Mostimportant,

thatLRM estimatescan be generatedwith 1 yr of

ratherthana minimumof 3 yrof data

surveyeffort

estimatesofpopulationsize.

requiredforJolly-Seber

DIsCUssIoN

the

manyofthetestedassumptions,

Despitemeeting

modelwas a poor estimatorof No

Leslie regression

JAMES P. WARD, JR. ET AL.

212

1985

EcologicalApplications

Vol. 1, No. 2

personalobservation).

Also,homerangesize forindi210

vidualsduringthisperiodrangedfrom0.6 to 2.3% of

(11,19)

129

thestudyarea (Solis 1983),indicating

thatfewhome

rangeswouldbe intersected

by studyarea boundaries

150(e.g.,see Whiteet al. 1982:122).Furthermore,

study

area boundarieswereestablished

to minimizemove112

mentsbyowlsacrossthem(Franklin

etal. 1990).Thus,

90immigration

and

emigration

were

considered

negligi(23,12)

71

70

63

165

~65

ble.

By

was

not

affected

61

definition,

by

and

births,

No

I58

5

54

52

mortality

duringthecensusperiodwas assumedto be

95

C/)

30

closetozerobasedon radiotelemetry

(Solis 1983)and

bandingdata(A. B. Franklin

et al., unpublished

data).

O >

1986

However,immigration

could be "mimicked,"and

o o 100

L1J4

henceclosureviolated,whenindividualsare counted

morethanonce.This sourceoferrorwas morelikely

o

~~~~~~~~~~~~89

(12,17)

02.

at

night

whenowlsweremobile(i.e.,hunting

ormoving

176

C/)c

80HQ4)

' 74

73

towardan observer

whowascalling),

itdifficult

making

7

forobservers

to inferowlidentity.

70

60

67

65

(7,14)

Moreover,thenumberof owls countedduringall

60

65

59

58

was >80% ofNo.Also,considering

home

daysurveys

U)06

rangesize forpairedowls(X = 676.8 ha),theproportionofhomerangeoverlapbetweenneighboring

owls

O

40

D

(X = 0.39) and thetotalamountofhabitatpotentially

used by SpottedOwls withinthe studyarea (12 626

1987

LL 3

ha; Solis 1983,Franklin

et al. 1990),we wouldexpect

O 0^ 100roughly({12626/[(1 - 0.39) x 676.8]} x 2) or 62

z_

adultandsubadultowlsinthestudypopulation.

There(24,12)

fore,theportionofthepopulationsampledappeared

76

80 79

75

(11,12)

76

adequate.Thisledus toconcludethattheoverestimate

67

71

67

producedby nightsurveysduring1985, and subseofNo in 1986and 1987werelikely

quentfluctuations

61

66

61

60 causedbyovercounting.

55

Regressionestimators

are notoriousforunderestimatingNo (Van Ettenet al. 1965,Lewis and Farrar

40

1968,Whiteetal. 1982,Schnute1983)and,underthe

JOL

COUNT

CAP

LRM

LRM

SEB

NIGHT

MBH

are infeDAY

assumptionof constantcaptureprobability,

riorto maximumlikelihoodestimators

(Whiteet al.

FiG. 3. Annualestimatesof the numberof territorial 1982:115).In addition,estimation

of V[NO]usingEq.

NorthernSpottedOwls in a 292.4 km2area near Willow

3

may

not

be

valid

because

regression

techniques

asModelacronyms,

beneathhorizontal

Creek,California.

axis,

andequalityoferrorterms(White

inparentheses

are:LRM = Leslieregression

arethe sumeindependence

(numbers

intervalin hoursusedto groupcensusdataand samplesize et al. 1982:116).However,our LRM estimatesare

CAP-MBH = generalremoval comparableto maximumlikelihoodestimators

of regression,

respectively);

and,

methodofprogram

re- therefore,

CAPTURE; JOL-SEB= Jolly-Seber

robust

when

are

used

to

appear

day

surveys

ducedparameter

(D); COUNT = directcountofowls.

estimate

CountsofSpottedOwlsduring

Noand V[NO].

thedayprovideadequateestimates

ofNowheninput

when nightsurveyswere used. The LRM will work intotheLRM because,all otherconsiderations

equal,

only if the number of individuals captured declines it is unlikelythatindividualsare miscounted

when

over time (Krebs 1989). A plot of cumulativenumber visuallyobservedat daytimeroosts.

of individual owls detected at nightas a functionof

Relativedifferences

werecalculatedusinga total

cumulative hours expended duringnightsurveyswas count(Nm)as a reference

value.Becausedirectcounts

linearforeach year,indicatingthatthe"catch" did not invariably

resultin an underestimate

ofthetruepopdecline.The same plot forday surveyswas curvilinear, ulationsize (Caughley1977),our estimates

of differencelikelyrepresented

showingfewerowl detectionsover time.

minimum

differences

between

Capture rates will not decline if population closure Noand No. However,evaluationof therelativeperis violated or a large enough portion of the studied formance

amongmodelswas valid becausethesame

in all calculations.

population is not sampled (Zippin 1956, White et al. value was referenced

Total counts

1982). With few exceptions,Spotted Owls were site probablyrepresented

90-95% of theterritorial

popufaithfulduringthe census period (A. B. Franklinet al., lation.This judgmentwas based on the amountof

{

v

v

cD

{

52

May 1991

ESTIMATING OWL ABUNDANCE

suitable habitat presentand the number of repeated

visits to territorieswhereowls were not detectedafter

the firstvisit each year (maximum = 21 visits).

Observercharacteristicscould affectcountsof birds

(Verner 1985). Surveys in 1985 and 1986 were conducted by the same two observers,with2 and 4 yrof

experiencein callingand locatingowls at thebeginning

of the 1985 census. All observationswere verifiedby

both observers.Despite this level of observerexperience, the LRM overestimatedNmusing nightcounts

and underestimatedNm using day counts, indicating

that at least two census periods may be necessaryfor

reliableestimates.In 1987, one of the originalobserverswas replacedwithless experiencedobservers.However, priortrainingof new observerscoupled withresidual expertise of the remainingoriginal observer,

preventedany noticeable loss of information.

Our results suggestthat the LRM can be used to

estimatethe numberof territorialadult and subadult

SpottedOwls presentat thebeginningoftheirbreeding

season, and to estimatea measure of precision.Given

the same studydesign,No can be convertedto crude

or ecological density(Franklinet al. 1990). Although

nocturnalcounts should not be used forestimatingNo

with the LRM, nightsurveysare usefulforassessing

the generalvicinityof owl roost sites. Once owls are

visually observed at roosts,theycan be counted with

littleduplication;nestscan be locatedand reproductive

parameterssampled with littleextra effort(Forsman

1983, Franklinet al. 1990). Thus, day surveys,in combination with the LRM, would provide more informationforland managementdecisionsthannightsurveys alone.

We recognizethat the use of the LRM with direct

count data is not a substituteformark-recaptureexperiments,as the latterprovide informationon survivorship, recruitment,and dispersal in addition to

estimatesof N,. However, the LRM will providea less

expensive,simpleralternativeforestimatingand monitoringabundance ofterritorial

SpottedOwls and other

speciesthatbehave similarly.Additionaltestingofthis

methodis recommended,particularlyto assess effects

of observerexperience,geographicvariation,and species variationon model estimates.

213

PSW-87-001ICA), and theMcIntire-Stennis

Program

(HSU

ProjectNumber85).

LITERATURE CITED

Bias, M. 1989. Habitatuse by California

SpottedOwlsin

thecentralSierraNevada. Thesis.HumboldtStateUniversity,

Arcata,California,

USA.

Burnham,

K. P., D. R. Anderson,

and J. L. Laake. 1980.

Estimation

of densityfromlinetransect

samplingofbiologicalpopulations.

Wildlife

Monographs

72.

Carey,A. B., J.A. Reid,and S. P. Horton. 1990. Spotted

Owlhomerangeandhabitatusein southern

OregonCoast

Ranges.Journal

ofWildlife

Management

54:11-17.

Caughley,

G. 1977. Analysisofvertebrate

populations.

Wiley,London,England.

Dawson,W. R., J.D. Ligon,J.R. Murphy,

J.P. Myers,D.

Simberloff,

and J.Verner.1987. Reportoftheadvisory

panelon theSpottedOwl. Condor89:205-229.

Forsman,E. D. 1983. Methodsand materials

forlocating

and studying

SpottedOwls.UnitedStatesForestService

GeneralTechnicalReportPNW-162.

Forsman,E. D., E. C. Meslow,and H. M. Wight. 1984.

Distribution

and biologyof the SpottedOwl in Oregon.

Wildlife

Monographs

87.

Franklin,

A. B.,J.P. Ward,R. J.Guti6rrez,

andG. I. Gould.

1990. DensityofNorthern

SpottedOwlsinnorthwest

California.

Journal

ofWildlife

Management

54:1-10.

Ganey,J.L., andR. P. Balda. 1988. Distribution

andhabitat

use ofMexicanSpottedOwlsin Arizona.Condor91:355361.

Ganey,J.L., and R. P. Balda. 1989. Home rangecharacteristics

of SpottedOwls in northern

Arizona.Journalof

Wildlife

Management

53:1159-1165.

R. J.,A. B. Franklin,

Gutierrez,

W. S. LaHaye,V. J.Meretsky,

and J.P. Ward. 1985. Juvenile

SpottedOwl dispersalin

northwestern

California:

results.Pages60-65

preliminary

in R. J. Guti6rrez

and A. B. Carey,editors.Ecologyand

of SpottedOwls in the PacificNorthwest.

management

UnitedStatesForestServiceGeneralTechnicalReport

PNW-185.

Jolly,

G.M. 1965. Explicit

estimates

from

capture-recapture

data withbothdeathand immigration-stochastic

model.

Biometrika

52:225-247.

Krebs,C. J. 1989. Ecologicalmethodology.

Harper& Row,

NewYork,NewYork,USA.

Kulchler,

A. W. 1977. The mapofthenaturalvegetation

of

California.Pages 909-938 in M. Barborand J. Majors,

editors.Terrestrial

ofCalifornia.

vegetation

JohnWiley&

Sons,New York,New York,USA.

LaHaye,W. S. 1988. Nestsiteselection

andnesting

habitat

oftheNorthern

SpottedOwl(Strixoccidentalis

caurina)in

northwestem

California.

Thesis.HumboldtStateUniversity,Arcata,California,

USA.

Laymon,S. 1988. EcologyoftheSpottedOwlinthecentral

SierraNevada,California.

Dissertation.

ofCalUniversity

ifornia,

Berkeley,

USA.

California,

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Leslie,P. H., and D. H. S. Davis. 1939. An attemptto

We are indebtedto T. J. Evans,C. A. Moen,and K E.

determine

the absolutenumberof ratson a givenarea.

Youngfortheirdevotedassistancein collecting

and entering Journal

ofAnimalEcology8:94-113.

data,to G. M. Allen,C. H. Biles,and B. R. Noon fordis- Lewis,J.C., andJ.W. Farrar.1968. An attempt

to use the

cussionson mathematical

procedure,

and to E. D. Forsman

Leslie censusmethodon deer.Journalof WildlifeManand W. S. LaHaye fordiscussionsof fieldtechniques.

The

agement

32:760-764.

computer

skillsofD. Call and R. Watersare Norton,B. 1988. Commodity,

programming

amenityand morality,

the

also greatly

appreciated.

D. R. Anderson,

R.

limitsofquantification

J.A. Blakesley,

invaluingbiodiversity.

Pages200J.Cooper,J.L. Ganey,D. G. Hankin,J.Vemer,T. A. Weist,

205 inE. 0. WilsonandF. M. Peter,editors.Biodiversity.

and G. C. Whitekindlyrevieweddraftsofthismanuscript. NationalAcademyPress,Washington,

D.C., USA.

Thisresearch

was fundedbyCalifornia

ofFish Otis,D. L.,K. P. Burnham,

Department

G. C. White,andD. R. Anderson.

and Game (FederalAid in WildlifeRestorationProjects

1978. Statistical

inference

fromcapturedata on closed

W-65-R-3

and4),U.S. ForestService,

animalpopulations.

Pacific

Southwest

Range

Wildlife

62.

Monographs

and Experiment

Number Peterson,

R. 0. 1988. The pit or thependulum:issuesin

Station(CooperativeAgreement

214

JAMES P. WARD, JR. ET AL.

EcologicalApplications

VnV I Nn- 2

in naturalecosystems.

APPENDIX

largecarnivore

management

Pages

105-117in J. K. Ageeand D. R. Johnson,

editors.EcoExamplecalculations

ofvariablesinputintotheLesliereforparksand wilderness.

systemmanagement

University gression

model,givena 23-hgrouping

ofthecumulative

numofForestResourcesContributionberofSpottedOwlsdetectedand thecumulative

ofWashington

Institute

numberof

Number65. Universityof WashingtonPress, Seattle, hoursof effort

devotedduring1985 daytimesurveysin a

Washington,

USA.

292.4 km2areanearWillowCreek,California.

Reynolds,R. T., J. M. Scott,and R. A. Nussbaum. 1980.

A variablecircularplotmethodforestimating

birdnumPersampling

bers.Condor82:309-313.

Cumulative

data

interval Regression

data

Salwasser,H. 1988. Managingecosystems

forviablepopOwls

Owls

ulationsofvertebrates:

a focusforbiodiversity.

Pages87Cum.

detect- prev.

104 in J.K. Ageeand D. R. Johnson,

editors.Ecosystem Survey

no.

No.

No.

ed per demangement

forparksandwilderness.

University

ofWash- interval

No. survey owls hours hour tected

ingtonInstitute

ofForestResourcesContribution

Number

()

(n)

(Y)

(X)

65. University

ofWashington

Press,Seattle,Washington, (1) owls hours

USA.

1

2

0.83

4

2.57

Salwasser,

H., I. D. Luman,and D. Duff. 1982. Integrating

6

5.17

wildlife

and fishintopubliclandforest

management.

Pro8

7.23

ceedingsoftheWestern

AssociationofFishand Wildlife

10

8.40

Agencies62:293-299.

12

10.03

Schnute,

J. 1983. A newapproachtoestimating

populations

13

16.70

bytheremovalmethod.CanadianJournal

ofFisheries

and

15

21.20

15 21.20 0.708

0

AquaticSciences40:2153-2169.

Seber,G. A. F. 1965. A note on the multiplerecapture

2

16

24.77

18

census.Biometrika

27.50

52:249-259.

20

29.03

1982. The estimation

ofanimalabundanceandre21

35.03

lated parameters.

Second edition.Griffin,

London,En22

35.83

gland.

24

35.93

1986. A reviewof estimating

animalabundance.

25

38.80

Biometrics

42:276-292.

26

45.93

11 24.73 0.445

15

Sisco,C. L. 1990. Seasonalhomerangeandhabitatecology

ofSpottedOwlsin northwestern

California.

Thesis.Hum3

27

48.10

29

boldtStateUniversity,

50.90

USA.

Arcata,California,

31

55.77

Solis,D. M. 1983. SummerhabitatecologyofSpottedOwls

32

6

65.37

19.44 0.309

26

in northwestern

California.

Thesis.HumboldtStateUniversity,

Arcata,California,

USA.

4

33

70.73

Thomas,J.W.,L. F. Ruggiero,

R. W. Mannan,J.W. Schoen,

34

74.27

and R. A. Lancia. 1988. Management

and conservation

35

3

78.03

12.66 0.237

32

ofold-growth

in theUnitedStates.Wildlife

forests

Society

5

36

101.77

Bulletin16:252-262.

38

3

113.70

35.67 0.084

35

UnitedStatesForestService. 1988. Finalsupplement

tothe

6

39

121.90

environmental

foran amendment

impactstatement

to the

41

3

125.67

11.97 0.251

38

PacificNorthwest

regional

guide.UnitedStatesForestService,Portland,

Oregon,USA.

7

43

2

142.80

17.13 0.117

41

VanEtten,R. C., D. F. Switzenberg,

andL. Eberhardt.1965.

8

45

2

180.83

38.03 0.052

43

ina square-mile

Controlled

deerhunting

enclosure.

Journal

47

9

188.43

ofWildlife

29:59-73.

Management

48

200.63

Verner,

J. 1985. Assessment

ofcounting

techniques.

Pages

49

201.23

4

20.40 0.196

45

247-302 in R. F. Johnston,

editor.Currentornithology.

10

50

207.27

Volume2. Plenum,New York,NewYork,USA.

51

210.73

K. P. Burnham,

and D. L.

White,G. C., D. R. Anderson,

52

3

216.90

15.67 0.191

49

Otis. 1982. Capture-recapture

and removalmethodsfor

Los AlamosNationalLabosamplingclosedpopulations.

11

54

239.50

Publication

LA-8787-NERP.

ratory

55

250.10

56

4

250.27

33.37 0.120

Secondedition.Pren52

Zar,J.H. 1984. Biostatisticalanalysis.

NewJersey,

USA.

tice-Hall,EnglewoodCliffs,

12

57

1

266.27

16.00 0.063

56

Zippin,C. 1956. An evaluationoftheremovalmethodof

animalpopulations.

Biometrics

12:163-169.

estimating