Document

advertisement

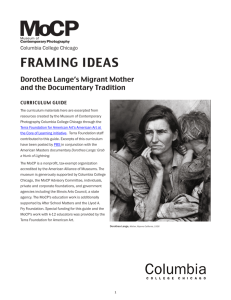

Danita R. Campbell Professor Studebaker-Coppage ENGL 1102-DD 2 February 2011 Essay 1 During the Great Depression President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal created several work relief and action programs to combat rampant unemployment, food shortages, and stimulate the nation’s economy. One such program was the Farmer Security Administration. Tasked with teaching Dust Bowl farmers about soil conservation and erosion, the FSA needed a way to document its progress and make urban Americans aware of the plight of rural families. To fulfill that need, the FSA created a historical department and named Roy Stryker chief. Stryker hired a group of photographers to visually document the people and places of rural America. Dorothea Lange was one of the photographers chosen by Stryker to provide a glimpse into the lives of farm workers. Lange’s work garnered much attention for migrant workers of that era and has since become iconic. What is remarkable about Lange’s photography is her ability to draw a viewer into the story she tells with images. In March of 1936, Lange took a series of pictures, one of which came to be known as the Migrant Mother. The photos depict a California family of pea pickers at a farm where the crops had frozen in the fields. In the first photo, the mother and four of her seven children are seen in a small tent with their meager possessions. With each successive frame, the background is cut away until the mother; Florence Owens Thompson becomes the focal point. In the last picture, the faces of Thompson’s children are turned away from the camera and even she does not look directly into the camera. There is a look of grim determination on her face. One would almost Campbell 2 think she was looking past her current circumstances and possibly searching for an answer to their questionable situation. In an interview in Popular Photography, Lange says, “There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.” (Lange) In fact Lange was a huge help to the migrant families of that camp. A friend of Lange’s was editor of a San Francisco newspaper. He printed a story about the desperate conditions at the migrant camp and used two of the pictures of Mrs. Thompson in the article. He also contacted federal authorities who rushed a shipment of 20,000 pounds of food to the camp. Lange’s work was also included in articles written by John Steinbeck and inspired the great American novel, The Grapes of Wrath. It is generally acknowledged that Lange’s Migrant Mother is iconic and is even called the face of the great depression. However a shadow overhangs the work of Lange and others in the historical department of the FSA. The work of Lange and others was supposed to be documentary in nature and as such real and not staged. Documentary photography is supposed to capture what is and should not arrange features to form images. A very controversial photo taken by FSA photographer Arnold Rothstein depicted a bleached skull of a longhorn steer. The photo was visually stunning, but when the press learned of Rothstein’s manipulation of the skull to achieve dramatic effect, they were outraged. The ensuing uproar almost caused the Historical department of the FSA to be shut down. The photographers of the FSA as well as Roy Stryker defended their pictures. The FSA did not create the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl,or the circumstances created by these events, so it stands to reason that it did not matter how the skull was arranged in the photo. The steer was still dead and the Mrs. Thompson did not have adequate food or shelter. Critics of the New Deal called the photographs taken by Lange and her colleagues liberal propaganda designed Campbell 3 to sell the idea that the new social programs were working when in fact the numbers of unemployed workers were still significantly high and the gross domestic product was only half of what it had been before the stock market crash in 1929. (Curtis) While the FSA certainly did not seek to hoodwink the American public, they did intend to persuade the public to believe what they saw in the FSA photos was the unadulterated and unvarnished truth. The adage, the camera does not lie is certainly true because the camera is just a tool. In the hands of a person, however, the camera becomes a vehicle for expression. Dorothea Lange saw poverty and desperation in a migrant camp and she wanted to convey those images to the American public in a way that would evoke empathy. Whether she or the other photographers of the FSA crafted the images to stir the viewer’s emotions is debatable but the pathos evoked by the Migrant Mother is palpable. The lines of worry and work etched across Mrs. Thompson’s face draw the viewer into her world. One can sense the quiet desperation of a mother holding a listless baby surrounded by children in what appears to be a cold barren environment. There is no fire and no evidence of food preparation. Even if the picture was staged, Dorothea Lange succeeded in capturing the essence of Mrs. Thompson’s struggle to survive and presenting it to the viewer in an immediately understandable fashion. Mrs. Lange did not have access to the team at Industrial Light and Magic, a film production company owned by George Lucas, what she did have was a camera and a discerning eye. Armed with those tools she set out to document the human condition during the depression and considering the long lasting notoriety of her work, we can say, “Well done Mrs. Lange, well done.” Campbell 4 Works Cited Barnet, Sylvan, and Hugo Adam Bedau. “Visual Rhetoric Images as Arguments.” Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing: A Brief Guide to Argument. 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011. 164. Print Curtis, James. Mind’s Eye, Mind’s Truth: FSA Photography Reconsidered. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989. 212. Print Lange, Dorothea. “The Assignment I’ll Never Forget: Migrant Mother.” Popular Photography Feb. 1960: 42+. Print