Corporate Parenting - Kent County Council

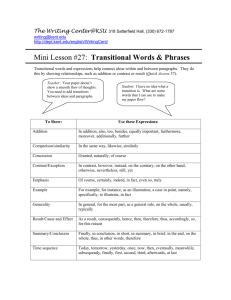

advertisement