gst and financial supplies - Journal of Australian Taxation

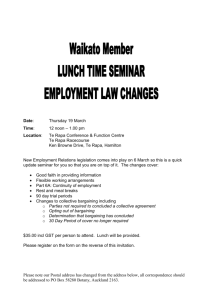

advertisement