367 INSURANCE IN A BAILMENT This article examines the issues

advertisement

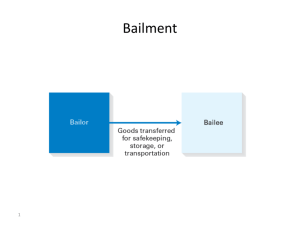

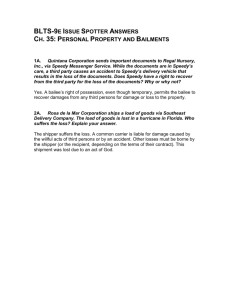

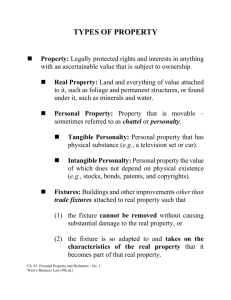

7 S.Ac.L.J. Insurance in a Bailment 367 INSURANCE IN A BAILMENT This article examines the issues of insurable interest (the rights of the bailor and bailee to insure) and contribution (the relationship between the bailor’s and bailee’s insurers) in relation to insurance in a bailment scenario. 1. INTRODUCTION The owner of goods obviously has an interest in protecting his property by means of insurance. He can obtain a number of policies covering a variety of risks, but when a loss occurs, he can recover no more than the value of his loss. Very often, someone other than the owner may also be interested in insuring the same goods against loss, for example, a bailee. A bailee does not have title to the goods, but as he has possession of them, he may be legally responsible for the safekeeping of the goods, and hence it is common for a bailee to obtain insurance coverage. Thus the same goods may, at the same time, be covered under the owner’s policy as well as the bailee’s policy. The purpose of this article is to discuss the rights of the bailor and the bailee to insure goods under a bailment and also to consider the rights of the bailor’s and bailee’s insurers inter se when a loss occurs. 2. BAILMENT DEFINED It has been said that a bailment is incapable of precise legal definition because it covers many different relationships1. Be that as it may, for the purposes of this article, the bailment can be simply described as the delivery of goods by the owner (bailor) to another (bailee) on the condition that they will be restored by the bailee to the bailor, or according to his directions, as soon as the purpose for which they are bailed shall be answered2. Thus the bailee is essentially the person to whom the possession of goods has been entrusted by the owner (the bailor) who retains title or ownership. 3. WHO CAN INSURE? Where the bailor or the bailee wishes to effect their own insurance on the goods comprised in the bailment, they must have insurable interest in the goods. Although there is no statutory requirement of insurable interest for non-life insurance3, nonetheless, insurable interest is still required at the 1 2 3 see ELG Tyler & NE Palmer, Crossley Vaines’ Personal Property, 5th ed, Butterworths 1973, at page 70. see Osborn’s Concise Law Dictionary, 6th Ed, John Burke, Sweet & Maxwell, 1976. It must be noted that Section 64 of the Insurance Act does not apply to indemnity insurance. This is consistent with the view taken by the Privy Council on appeal from Hong Kong (Siu Yin Kwan v Eastern Insurance Co Ltd [1994] 1 All ER 213) that the UK Life Assurance Act 1774 Act (which is similar to s.61A) did not apply to indemnity insurance. 368 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1995) time of loss because a non-life insurance is essentially a contract of indemnity4. In the absence of any interest and if the insurance contract is purely speculative, it could be rendered void and unenforceable by S.6 of the Civil Law Act for being a wagering or gaming contract. Insurable interest has been defined by Lord Eldon in Lucena v. Crawford 5 as a “right in the property, or a right derivable out of some contract about the property, which in either case may be lost upon some contingency affecting the possession or enjoyment of the other party.” So a person would have insurable interest in a thing if he will be financially prejudiced by its loss because he has a legal, equitable or contractual right to the thing insured. Insurance in a bailment scenario would be an insurance on goods. The bailor, being the legal owner of the goods, would suffer a financial loss if the goods should suffer damage or loss and so clearly has insurable interest. The question is whether the bailee has insurable interest to insure the goods. It was decided in Marks v. Hamilton6 that a person who was in possession as apparent owner, responsible to those who were the real owners and who can be called on to account for property has insurable interest. This is because possessory title is a good root of title in common law, good against everyone except the legal owner and hence, possession coupled with a legal liability such as that which arises in a bailment7 would give rise to insurable interest. Hence even the gratuitous bailee would have insurable interest simply by virtue of the personal liability that may arise from his responsibility for the goods and his corresponding duty to account to the bailor. The next issue is whether the bailee has insurable interest in the absence of liability in respect of those goods. An insurance of goods is a contract of indemnity and hence it is necessary for an insured to show that he has insurable interest at the time of the loss. The question here is whether a bailee who is not responsible for the loss of the goods has an interest that entitles him to claim insurance. The answer to this question is found in the decision of Waters v. Monarch Fire and Life Assurance Co8 where it was held that bailees could insure the goods entrusted to them and in the event of loss, still claim the full value of the damage, irrespective of liability. In this case, flour and corn factors (bailees) effected floating policies over 4 5 6 7 8 Life and personal accident insurances are not regarded as indemnity insurance but all other types of insurance are indemnity insurance. (1806) 2 B&PNR 269. (1852) 7 Exch 323. Holt CJ in Coggs v Barnard (1703) 2 Ld Raym 909, identified six different categories of bailments and said that the bailee in all cases of bailment is liable for negligence. (1856) 5 E&B 870. 7 S.Ac.L.J. Insurance in a Bailment 369 goods in their warehouse, whether their own or those held in trust or on commission. A fire destroyed all the goods in the warehouse under circumstances that imposed no liability on them for the loss. First, it was decided that as a matter of construction, the policies were not intended to be limited to the personal interest of the plaintiffs because the promise in the policies was to make good the damage to the goods. As the property was wholly destroyed, the insurers had to make good the whole value and not merely the personal interest of the bailees. Lord Campbell CJ also added that such policies were not illegal. Indeed, if they were not allowed, “it would be most inconvenient in business if a wharfinger could not, at his own cost, keep up a floating policy for the benefit of all who might become his customers.” Hence, it was decided that the bailees could recover their own interest in the goods and would be regarded as trustees of the remainder for the owners of the goods. The court’s decision in Waters v. Monarch Fire and Life Assurance Co clearly had its merits, as it resulted in convenience and business efficacy. It also benefitted the uninsured bailor who would otherwise have no recourse for his loss. Nonetheless, the question remained whether such a policy (where the bailees had insured the goods and were allowed to recover in the absence of personal loss or liability) was consistent with the requirement of insurable interest in indemnity insurance. The court had another opportunity to address this issue of insurable interest in Hepburn v. Tomlinson (Hauliers) Ltd9 , where the House of Lords approved and upheld the decision in Waters v. Monarch Fire and Life Assurance Co. The clearest explanation in resolving the issue is found in the judgement of Lord Pearce. His lordship, after considering the position of the agent who had no interest but yet insures for others, said, “The bailee of goods is in a very different position. He has a right to sue for conversion, holding in trust for the owner such of the damages as represent the owner’s interest. He may likewise sue in negligence for the full value of the goods, though he would have had a good answer to an action by the bailor for the loss of the goods bailed (The Winkfield 10) .” 11 Thus in Lord Pearce’s view, “A bailee or mortgagee, therefore (or others in analogous positions), has, by virtue of his position and his interest in the property, a right to insure for the whole of its value, holding in trust for the owner or mortgagor the amount attributable to their interest. The hold otherwise would be commercially inconvenient and would have no 9 [1966] AC 451. 10 [1902] p 42; 18 TLR 178, C.A. 11 at pg 480. 370 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1995) justification in common sense. In my opinion, there is no burden on him to prove his intention to insure their interest on their behalf. If, however, the defendants can affirmatively prove that he had an intention not to do so, his insurance quoad that other interest is gaming and he cannot recover.”12 In this case, carriers effected a goods in transit policy on tobacco which was stolen under circumstances attaching no legal liability to them. The owners of the goods had been expressly named in the policy and the conditions were those appropriate to a first party and not a liability policy. The House of Lords held that the carriers were entitled to recover the full value of the tobacco for the benefit of the owners and it was not necessary to prove that they had intended to insure for interest of the owners. Thus the bailee’s insurable interest was analyzed in terms of the principles of the law of agency. When a bailee effects goods insurance, the presumption in law is that he is insuring and claiming losses as an agent for and on behalf of his principal, the bailor. In this respect though, there need not be actual authority from the bailor. In fact, Lord Campbell CJ observed in Waters v. Monarch Fire and Life Assurance Co13, that the bailee can insure the goods “without the orders from the owner and even without informing him that there was such a policy”. The bailee, in accordance with principles of agency, can take out insurance cover for a disclosed14 or undisclosed principal. It has also been acknowledged that this presumption of agency is rebuttable if it can be shown that, in effecting the insurance, the bailee did not have the intention of benefitting the bailor. In any case, it is now beyond question that bailees can legally effect goods insurance and claim the full value of the loss even though they may not have suffered any loss nor incurred any personal liability, provided they claim for the benefit of the bailor. This must be so because the bailee otherwise has no business insuring the property in goods which do not belong to him but to others. For this reason, it is important to distinguish between a personal liability policy where the bailee only insures up to the value of his personal interest, and a goods policy where the bailee insures up to the full value of the goods on behalf of other interested parties. Bailees would not be able to recover the value of the goods on behalf of the bailor if the insurance extended to “goods in trust or on commission, for which they (the bailees) are responsible”. This would be a personal liability insurance instead of a goods insurance. In North British and Mercantile Insurance Co v Moffatt15 , the court construed similar words in 12 at pg 481 to 482. 13 at pg 709. 14 this would be the case if the bailor is named in the bailees’ policy as the owner of the goods — see Hepburn v. Tomlinson (Hauliers) Ltd, (note 8). 15 (1871) LR 7 CP 25. 7 S.Ac.L.J. Insurance in a Bailment 371 a policy and held that the insurers had limited their liability to the responsibility of the insured. Since the property in the insured goods had, at the time of the fire, already passed to the purchasers, the bailees in question, who no longer had any interest nor responsibility in respect of the goods, were not covered by the policy. This issue concerning the bailee’s right to claim insurance was considered by the Singapore High Court in Sui Brothers (Pte) Ltd v Norwich Winterhur Insurance (Far East) Pte Ltd16 . The plaintiffs, traders and commission agents in the sale and delivery of goods, effected insurance against theft with the defendants. The property insured was described as: “On stock in trade of general merchandise, canned food, machinery and parts, textile cotton yarn, garment and the like, the property of the insured or held by them in trust or on commission for which they are responsible situate Block 3017 Ubi Road 1 #02-131 Singapore 1440.” The plaintiffs claimed a loss of 2006 cans of abalone which had been stolen from the insured premises. The plaintiffs had also provided finance for the purchase of the insured goods. Their agreement with the purchasers stated that if the purchasers failed to pay the balance of the price when the goods arrived in Singapore, the goods would be stored (the purchasers to pay storage charges) at the plaintiffs’ warehouse without any risks on their part, thus making the plaintiffs the pledgees of the goods as well. The case came before the court on a trial of a preliminary issue whether the stolen goods were within the description of property contained in the policy. The first issue was whether the plaintiffs were bailees. Goh Phai Cheng JC decided that the plaintiffs were bailees because they had taken possession of the insured goods as warehousemen and pledgees. Next, (following the earlier decisions in North British and Mercantile Insurance Co v Moffatt and Hepburn v. Tomlinson (Hauliers) Ltd), it was decided that the policy was not an insurance on goods, but covered only the bailees’ personal liability to the bailor. As for the agreement between the plaintiffs and the purchasers which had exempted the plaintiffs’ from liability, Goh JC said that this exemption was specified to be in relation to the plaintiffs’ liability as warehousemen. In the absence of clear and unambiguous language, the exemption could not be relied on to exclude their liability as pledgees. Hence the plaintiffs could remain liable as pledgees of the goods if the theft had indeed been caused by any default on their part. If that was the case, the loss of the cans of abalone would be recoverable under the policy. 16 [1993] 2 SLR 173. 372 4 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1995) SUBROGATION Having considered the respective rights of the bailor and bailee to insure the goods comprised in the bailment, the next question to be considered is the rights of the bailor’s insurers vis-a-vis the bailee’s insurers in the event of a loss. In insurance law, an insurer who has indemnified the insured for a loss, is given the right of subrogation, to be put in the place of the insured and to take any rights and remedies that he may have against the party who was responsible for the loss. The leading case on subrogation arising from insurance in a bailment is the decision in North British and Mercantile Insurance Company v London, Liverpool, and Globe Insurance Company17 . A firm of wharfingers effected floating policies of fire insurance over grain and seed, “the assured’s own, in trust, or on commission, for which they are responsible”. Grain belonging to a firm of merchants (who had their own policies against fire) was destroyed by a fire while it was stored with the wharfingers. The wharfingers’ insurers paid out the losses in full and the issue before the Court of Appeal was whether the merchants’ insurers were liable to contribute to the loss as well. Under the particular terms of that bailment, the wharfingers were absolutely liable in the event of a loss by fire. As such, the merchants’ insurers were not liable to contribute to the loss. The wharfingers (bailees) were insured in respect of their own interest and personal liability. It was observed by the court that if the merchants’ insurers (instead of the wharfingers’ insurers) had paid the losses, they would have been entitled to exercise their right of subrogation against the bailees and the bailees’ insurers would ultimately have been liable for the loss. Thus it can be seen that a crucial element for the exercise of subrogation is the existence of the bailees’ personal liability. Where the bailees are liable for the loss, the bailees’ insurers are responsible for the loss to the exclusion of the bailors’ insurers. 5. CONTRIBUTION Aside from subrogation, another consequence that can arise when the bailor and the bailee have both insured the goods is the right of contribution among the insurers. The right of contribution is based on the principle of indemnity. An insured is entitled to effect more than one policy on the same risk. However, in the case of indemnity policies, he is not entitled to recover more than an indemnity at the time of loss18. The principle of 17 (1877) 5 Ch D 569 C.A. 18 Brett LJ in Castettion v Preston (1833) 11 QBD 380 said that “the contract of insurance ... is a contract of indemnity, ..., and this contract means that the assured, in the case of a loss ..., shall be fully indemnified, but shall never be more than fully indemnified.” 7 S.Ac.L.J. Insurance in a Bailment 373 indemnity thus ensures that the insured is indemnified for his loss but does not allow the insured to profit from his loss. So in a situation where a person has effected two or more insurances on the same risk and same property (ie; there is double insurance), the insured is entitled to make a claim against any one of the insurers who would be bound to pay for the loss, up to the insured amount. The insured may claim from more than one insurer where the different insurers are providing insurance in different layers, for example there could be a primary insurer who is liable for the first loss and a secondary insurer who is liable for losses in excess of the primary insurer’s liability. However, in other situations where the insurers are all equally liable for the same loss, the insured would not be entitled to claim against all the insurers if it would result in him making a profit. Since the insured, may, at his option, call upon any one of the insurers to indemnify his loss, it would be unfair to that particular insurer to have to bear the entire loss. Indeed, the question of which insurer would be liable for the loss would ultimately be decided by a question of chance, when all of them were liable and could have been called upon to pay. In this context therefore, equity confers on the particular insurer who has indemnified the insured the right of contribution against the other insurers by calling on them to provide a contribution to the amount paid. The effect of the principle of contribution is that all insurers who are liable will then share the loss between themselves, in proportion to the amount covered under their respective insurances. It should be noted that this equitable right of contribution can be modified by contractual terms, for example, the rateable proportion clause, which states that the insurer is liable to pay only his proportion of the loss if there are other insurances covering the same risk. The effect of such a clause in a policy is to allow the insurer in cases of double insurance to pay only his share of the loss instead of paying the full indemnity and then claiming a contribution from the other insurer(s). This means that the insured would only succeed in recovering a rateable proportion of his loss from that insurer and he would have to claim the balance from the other insurer or insurers. 6. REQUIREMENTS FOR CONTRIBUTION Double insurance is defined19 as the situation “where two or more policies are effected by or on behalf of the same assured in respect of the same interest and the total of the sums assured exceeds what is required to secure to the assured a full indemnity”. Thus a right of contribution would arise when the following requirements are present. First, there must exist 19 Halsbury Vol 25: Insurance para 534. 374 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1995) more than one policy insuring the same subject matter against the same risk or peril. This does not mean that the two policies have to be identical in coverage, the requirement is that there must be an overlap in terms of coverage. Secondly, the policies must be made by or on behalf of the same insured, in relation to the same insurable interest. This can happen in compulsory motor insurance covering personal injury to third parties: for example, if the negligent driver has his own motor insurance and yet at the same time, is covered under his wife’s motor insurance while driving his wife’s car as the authorised driver. Lastly, both policies must be valid and enforceable. Where all these requirements exist, there is a case of double insurance which calls for contribution among the insurers. 7. DOUBLE INSURANCE IN BAILMENT Since contribution arises when the insured is covered by more than one insurance policy, it would clearly arise when either the bailor or the bailee each has more than one policy covering the same goods. In addition, the bailor and the bailee could each have effected a separate policy covering the same goods against the risk of fire or theft. The question is whether there could be a case of double insurance which would give rise to a contribution claim by either the bailor’s insurer against the bailee’s insurer or vice versa. In the case of a gratuitous delivery or loan of goods, the bailee is unlikely to have effected his own insurance on the goods. In cases of bailment for reward however, the bailee, being in this case a bailee in the course of business, would normally be covered by insurance. As for the bailor, he may or may not be covered by his own insurance, depending on the nature of the bailment. A trader whose goods are commonly carried or warehoused by a bailee for reward would probably have all risks insurance for his goods. On the other hand, a person who has contracted with a mover to have his belongings moved from one house to another may not even have contemplated, much less obtained, insurance coverage for the move. Thus the common instances when both the bailor and the bailee are insured would be where both parties enter into the bailment in the course of business. For contribution to arise, the first requirement is that there has to be two or more policies insuring the same property. In Boag v Economic Insurance Company Ltd20 , the insured, who owned two factories at Luton had insured some cigarettes loaded at one factory under an “all risks” transit policy. The cigarettes were transported to the other factory for one night where they were destroyed by fire. The “all-risks” insurers paid and claimed a 20 [1954] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 581. 7 S.Ac.L.J. Insurance in a Bailment 375 contribution from the insurers who had insured the other factory against fire under a policy which covered stock-in-trade, but not stock present temporarily. It was held that there was no contribution as the cigarettes were not covered by the second policy since they were merely temporarily present at the factory. In the case of a bailment, if the bailor has insured his own goods and if the bailee, as is common, effects insurance on goods held by him “in trust or on commission”, the same goods could easily be insured under two policies. The second requirement that there has to be two or more policies insuring the same risk is also easily satisfied in a bailment. As an example, both the bailor’s and bailee’s policies could insure against loss by theft or fire. The third requirement is that both the bailor’s and bailee’s policies must insure the same insurable interest. Where two persons have different insurable interests in the same property and each insures his own interest on his own behalf, there is no double insurance and therefore no right to contribution. This would happen in a bailment when the bailee has effected liability insurance and the bailor has insured as the owner of the goods. The bailee’s interest would arise when he has incurred liability for negligence in respect of the goods entrusted to him. The bailor’s interest would arise because he would suffer a financial loss in respect of his ownership of the goods. These interests differ and would not result in double insurance. In such situations, if the bailee is liable for the loss, the rights of the insurers inter se, would be more appropriately resolved by a subrogation claim by the bailor’s insurers against the bailee’s insurers (North British & Mercantile Insurance Co v London, Liverpool & Globe Insurance Co21 ) rather than a claim for contribution. However, in other cases, a bailee may insure the owner’s interest on his behalf with or without his consent, thus giving rise to double insurance of the owner’s interest if he has his own insurance at the same time. In Waters v Monarch, it was held that the bailee merchants were entitled to take sufficient cover to protect their own interest in the goods and may be regarded as trustees of the remainder for those parties who have the ulterior interest in the goods (that is, the bailors). This decision was affirmed by the House of Lords in Hepburn v Tomlinson (Hauliers) Ltd. These two cases are significant to the issue of contribution. Where the bailee has effected goods insurance and the bailor also has his own insurance and the loss is caused under circumstances which attribute no liability to the bailee, the two policies would overlap, thus giving rise to double insurance. As such, there would be a right of contribution between the insurers. 21 (1877) 5 Ch D 569. 376 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1995) The fourth requirement for double insurance exists when the same person has become entitled to the benefit of more than one policy, either directly as the insured or indirectly, by being a person who is entitled to the benefit of the insurance moneys22 ; for example, another policy on the same risk may have been entered into on his behalf. The bailor could be insured under the bailee’s policy, and if he also has his own insurance, there would be two policies covering the bailor’s loss: the former policy taken out on his behalf and the latter policy effected by himself. The courts have also expressed the view that the bailor’s knowledge of the terms of the bailee’s policy is not relevant23 . This view is consistent with the objective of contribution in achieving fairness between insurers in a situation where two or more insurers are liable and so it does not matter that both insureds are not aware of the existence of double insurance. Lastly, both the bailor’s and bailee’s policies must be valid and enforceable. In order to constitute double insurance, there has to be two or more valid insurance policies covering the same loss. The policies may be void or voidable under the usual grounds of illegality, fraud, mistake, misrepresentation or non-disclosure. The insurer may also be entitled to avoid liability on the ground of breach of a warranty or condition precedent in the policy. In addition, the validity of the policy can be affected by the existence of a non-contribution clause. The non-contribution clause in a policy provides that the insurer is not liable if the insured has another policy covering the same risk. The effect of such a clause is that in cases of double insurance, the insurer is not liable to pay at all, leaving the other insurer liable for the loss and hence there will be no right of contribution. However, if both the bailor’s and the bailee’s policies contain a noncontribution clause, both insurers remain liable for the loss24. Another question concerning the validity of the policies, is whether both policies must be enforceable at the time of the event giving rise to the loss or whether the policies must remain valid up to the time of the contribution claim. The problem arises in this situation: the policy could have been valid at the time of loss but by the time of the contribution claim, it could have been avoided by a subsequent breach of the policy. In Legal & General Assurance Society Ltd v Drake Insurance Co Ltd25 , the Court of Appeal decided that a contribution claim crystallises at the time of the loss (before 22 Lord Mansfield in Godin v London Assurance Company (1758) 1 Burr 489 at 492. 23 see note 12. 24 In Gale v Motor Union Insurance Co [1928] 1 KB 359, both policies had rateable proportion clauses and non-contribution clauses. Roache J decided that the rateable proportion clauses qualified and explained the non-contribution clauses, so both insurers had to contribute rateably. In Weddell v Road Transport & General Insurance Co Ltd [1932] 2 KB 563, both policies had only non-contribution clauses. According to Rowlatt J the reasonable construction was that both insurers were liable. 25 [1992] 2 WLR 157. 7 S.Ac.L.J. Insurance in a Bailment 377 the contribution claim) and so it was not affected by any breach of condition occurring after that time26 . The Privy Council on appeal from Bahamas in Eagle Star Insurance Co Ltd v Provincial Insurance plc27 however, decided not to follow the Court of Appeal’s decision and decided that the right to contribution is not to be determined at the date of loss because such an artificial cut-off date would not truly reflect the insurer’s true liability to the insured28 . It remains to be seen, when the issue arises in a future case, what the legal position in Singapore will be. 8. CONCLUSION The law clearly allows the bailor and bailee to protect their individual interests: the bailor by insuring the goods against damage or loss and the bailee by insuring against personal liability. In such a case, if the bailee is legally responsible for the loss, his insurers would bear the burden of the entire loss. Even if the bailor’s insurers had paid the loss, they would be entitled to be subrogated to the bailor’s rights against the bailee for negligence and the bailee would ultimately claim against their liability insurance. On the other hand, if the bailee is not liable, the loss will not be recoverable under his policy and only the bailor’s insurers will indemnify the bailor for his loss. Thus in situations where the bailee has taken out liability insurance, the question of contribution does not arise between the two insurers. Aside from insuring against personal liability, the law allows the bailee to insure the goods and recover losses on behalf of the bailor. In such a case, if the bailor is also insured and the bailee is not legally liable for the loss, both insurers will be required to contribute towards the loss. If both the bailee and the bailor have insured the goods but the bailee is liable for the loss, it will give rise to subrogation instead of contribution, leaving the bailee’s insurers to bear the burden of the loss. Thus it can be seen that the question of contribution between the bailor’s and bailee’s insurers arises only in that particular situation where the bailee has taken out goods insurance and bears no liability for the loss. There are actually very few decided cases in Singapore dealing with the issue of contribution between the bailor’s and bailee’s insurers, but that does not mean that double insurance rarely exists in a bailment. Instead, a probable reason for the lack of cases on the point could be due to the 26 approving the decision of Rowlatt J in Weddell v Road Transport & General Insurance Co Ltd [1932] 2 KB 563. 27 [1993] 3 WLR 257. 28 The Privy Council preferred the view of Rogers J in Monksfleld v Vehicle and General Insurance Co Ltd ([1971] Lloyd’s Rep 139) where the validity of the two policies was determined at the time of the contribution claim so that a breach of condition precedent in one of the policies relieved that insurer from their liability to contribute. 378 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1995) fact that the question is commonly resolved through the use of noncontribution and rateable proportion clauses in the policies. In any case, when double insurance exists, it benefits no one but the insurers because the goods could have been adequately covered under one policy instead of two. Hence it has been suggested that in order to avoid duplication, it would be advisable for the bailor and the bailee to decide who should be responsible for insurance coverage right at the start when the bailment is created29 . Bailees often have floating policies covering goods in their possession and the bailment would, invariably, only be created after the bailee’s insurance has been effected. If that is so, perhaps, the bailor would not need to effect his own insurance. The pitfall, however, is that the bailee’s insurance may not adequately cover the bailor’s interests in his goods. Another alternative for avoiding double insurance is for the bailee to take out only liability insurance instead of goods insurance. This however, would be to the detriment of the bailor if the goods are destroyed in circumstances imposing no liability on the bailee and if the bailor happens to be uninsured. To avoid this, the bailee who has only liability insurance, should advise the bailor to obtain his own insurance coverage. ERIN GOH-LOW SOEN YIN* 29 by N.E. Palmer, in “Bailments and the obligation to insure” (1992) 136 SJ 244. * Senior Lecturer, Division of Business Law, Nanyang Business School, Nanyang Technological University.