Oedipus Rex Packet Baker

advertisement

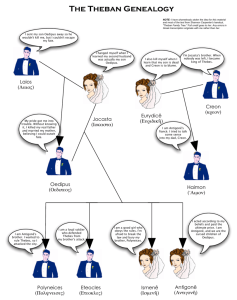

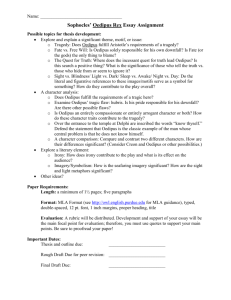

Oedipus Rex By Sophocles Literature & Composition Mr. Baker 2014 – 2015 Table of contents Setting/Background……………………………………………… 3 Reading sign ups……………………………………………………. 4 Vocabulary………………………………………………………….5 4 Corners……………………………………………………………. 6 Motif Tracking…………………….……………………………….7 Reading comprehension ?’s/Focused Annotation….…..… 8 Critical Readings……………………………………………….….17 Motif Essay assignment & Materials…………...………….. 23 Essential Questions: 1) How does art reflect and impact a culture’s values? 2) What are An individual's responsibilities to his/her society? 3) How does an author use motif to develop theme? Unit Objectives • • • • • • • Compare the role of fiction in ancient Greece and today. Describe the effect of authors’ word choices on meaning and mood. Identify how patterns of word choices and literary devices create a motif. Make claims about how motif contributes to theme development. Select appropriate evidence of motifs to support claims about theme. Analyze motif to show how it supports claims. Organize evidence and analysis to logically build support of claim. 2 Historical Setting for Oedipus Rex Title: Oedipus Rex (or Oedipus the King) Author: Sophocles, a Greek dramatist, 496-406 BCE Background of the Story of Oedipus Place: Thebes, a city in ancient Greece Events prior to the beginning of the play: Oedipus is a wanderer who leaves his home in his youth because he hears that the city of Thebes is under siege by the Sphinx. The Sphinx is a monster shaped like a winged lion with the breasts and head of a woman. The Sphinx waits on the roads to the city of Thebes, stops any traveler, offers a riddle, and if they fail to answer her riddle, she eats them. (According to legend, she kills by _______________________ her victim, thus giving us the modern word _______________________.) Her riddle is, “What creature walks on all four in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three in the evening?” Meanwhile, the king of Thebes, Laios, is murdered, but the city is too busy with the Sphinx to find revenge. Oedipus, courageous and intelligent, has nothing to lose, so he seeks out the Sphinx’s challenge. He answers the riddle (_________), and the Sphinx kills herself. To show their gratitude, the people of Thebes make Oedipus their king and Iocaste (pronounced with a “J”), the widowed queen, marries Oedipus. Four children later, Oedipus’ good times seem to have come to an end. A plague strikes the city of Thebes and the citizens and herds alike are dying from disease. Those alive are suffering from starvation and crowd the steps of the palace of King Oedipus, suppliants begging their king to help them out of their troubles once again. Players: Oedipus: King of Thebes Iocaste (pronounced with a “J”): Oedipus’ wife, was Laios’ wife Creon: Iocaste’s brother, counselor to Oedipus Teiresias: blind prophet of Thebes, counselor to Oedipus and Creon Choragos: leader of the Chorus; comes forward and interacts with other characters Chorus: Theban elders, a company of performers whose singing, dancing, and narration provide explanation and elaboration of the main actions; do not interact with other characters Priest: Theban elder with religious duties Messenger Shepherd of Laios: shepherd of former king Laios Second Messenger Important people or gods who are referenced: Kadmos: Legendary founder of Thebes Kadmos, Polydoros, and Labdakos: Laios’ paternal ancestors Menoikeus: Father of Iocaste and Creon Polybos and Merope of Corinth: Father and mother of Oedipus Athena (Pallas): goddess of wisdom and warfare; daughter of Zeus Apollo: god of the sun, god of music, poetry, prophecy, and medicine, represented as exemplifying manly youth and beauty; son of Zeus. Delphi, the location of the Delphic oracle and Pythian priestess, is dedicated to Apollo. Artemis: Apollo’s twin; goddess of the moon, the hunt, forests, and childbirth; daughter of Zeus 3 Reading Sign-ups Chorus Strophe 1: a-strophe 1: strophe 2: a-strophe 2: Strophe 3: a-strophe 3: _______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ Prologue Oedipus: Priest: Creon: _______________ _______________ _______________ scene 1 Oedipus: Choragos: Teiresias: _______________ _______________ _______________ scene 2 creon: choragus: Oedipus: Jocaste _______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ Scene 3 Choragos: Oedipus: Jocaste: Messenger: _______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ scene 4 Oedipus: Choragos: Messenger: Shepherd: _______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ êxodos 2nd mess: Oedipus: Choragos: Creon: _______________ _______________ _______________ _______________ 4 Vocabulary -Oedipus Rex-Fitzgerald Translation Study online at quizlet.com/_12kl3d 1. augury (noun) 2. 6. bane (noun) clairvoyant (adjective or noun) comely (adjective) courser (noun) defile (verb) 7. divination (noun) 8. duplicity (noun) 9. 12. execrable (adjective) expedient (adjective) flinty (adjective) haughty (adjective) 13. hearsay (noun) 14. impious (adjective) 15. 16. incarnate (adjective) infamy (noun) 17. insolence (noun) 18. lustration (noun) malediction (noun) overwrought (adjective) 3. 4. 5. 10. 11. 19. 20. 22. pallid (adjective) parricide (noun) 23. rankle (verb) 24. riven (adjective) 25. to maunder(verb) 21. prophecy; prediction of events [also: augur (noun)- one who makes predictions] a cause of harm, ruin, or death (adj.) supernaturally perceptive-seeing into the future ; (n.) one who possesses extrasensory powers, see having a pleasing appearance a swift-running horse To make unclean, impure; to pollute [Defilement=noun; defiled= adjective] (n.) the art or act of predicting the future or discovering hidden knowledge treachery, deceitfulness [Duplicitous= adjective] utterly detestable; abominable; abhorrent convenient; speedy extremely hard and firm; unyielding in character Arrogant, excessively proud and vain [Haughtiness= noun] A statement by a witness who did not actually see or hear an event, but who heard about it from someone else Disrespectful toward God [pious= very devout & religious] Embodied in human form. Disgrace, dishonor, bad reputation [infamous=adjective] (n) rude or impertinent behavior or speech [insolent= adjective] purification ; has a religious/ceremonial connotation A curse Excessively nervous or excited; agitated [wrought means "to work/worked" so the word translates to "too worked up" Lacking color; dull Killing one's father [you should be able to predict what many of these words mean based on prefix and suffix: regicide=killing of a king; suicide= killing of one's self; fratricide= killing one's brother] To cause anger, irritation, or bitterness [Adjective=rankled] torn apart; split [to rive= verb] to talk in a rambling, foolish or meaningless way [adjective= maundering] 5 “4 Corners”/Spectrum of Belief: You may choose to Agree, Strongly Agree, disagree or Strongly Disagree with the following statements. Then you must Explain WHY you feel the way you do. During the activity you will be asked to defend your claims. 1) “the greatest illusion we have is that denial protects us.”~Eve Ensler 2) IT is important to always strive for the truth. 3) Good leaders should follow the advice of those who they trust. 4) Other people know me better than I know myself. 5) “Denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial.” ~Elisabeth Kubler Ross 6) Self-Confidence is a positive character trait. 6 Motif Tracking While We Read Directions: Instead of annotating as you read, you will flag instances of various motifs throughout the text. Using post-­its, you need to assign each of the motifs a color and then mark them in your book every time they appear. You should use a post-­it to create a key in the front of your book. It should look like this: Motifs Related Terms Sight Assigned Color Light Family Justice 7 Reading Comprehension/Annotation Exercises Directions: Answer all questions in full and complete sentences. You need to include a direct quotation in at least TWO of your responses per section. Prologue: 1. How does Oedipus view himself? What type of leader does he say he is? 2. What is Oedipus’ attitude toward the suppliants (citizens begging for help)? 3. What are the conditions like in Thebes at the beginning of the play? What’s the “ethos” of the play? Look to the Priest description for help. 4. According to Creon, what does the Oracle say must be done in order to cure Thebes of the plague? 5. What prevented the citizens of Thebes from investigating Laios’ death? 8 Directions: Answer all questions in full and complete sentences. You need to include a direct quotation in at least TWO of your responses per section. Scene i: 1. Find an example of dramatic irony in Oedipus’ speech that begins scene 1. Explain how the example fits the definition. 2. What does Oedipus propose as a punishment for the murder? 3. Who is Teiresias? What is his reaction to Oedipus’ request for help? 4. Of what does Oedipus accuse Teiresias? 5. What does Teiresias reveal to Oedipus? Does Oedipus believe him? 6. What does Teiresias predict will happen to Oedipus? 9 Directions: Answer all questions in full and complete sentences. You need to include a direct quotation in at least TWO of your responses per section. Scene 2: 1. How does Choragos explain Oedipus’ behavior and accusations? 2. Does Creon regret calling for Teiresias? How do you know? 3. Why doesn’t Creon want to be king? Do you think his arguments are justified? 4. What does Iocaste think about soothsayers and predictions? 5. What is Oedipus’ story about Corinth? What happened there? 6. Why are Oedipus and Iocaste upset at the end of Scene II? 10 Directions: You may work with a group of 4 people to complete this assignment. Please annotate the ode and then summarize each stanza. Ode 2: Let me be reverent in the ways of right, Lowly the paths I journey on; Let all my words and actions keep The laws of the pure universe From highest Heaven handed down. For Heaven is their bright nurse, Those generations of the realms of light; Ah, never of mortal kind were they begot, Nor are they slaves of memory, lost in sleep: Their Father is greater than Time, and ages not. Summarize this stanza. How would you describe the tone? The tyrant is a child of Pride Who drinks from his great sickening cup Recklessness and vanity, Until from his high crest headlong He plummets to the dust of hope. That strong man is not strong. But let no fair ambition be denied; May God protect the wrestler for the State In government, in comely policy, Who will fear God, and on His ordinance wait. Summarize this stanza. How would you describe the tone? 11 Haughtiness and the high hand of disdain Tempt and outrage God’s holy law; And any mortal who dares hold No immortal Power in awe Will be caught up in a net of pain: The price for which his levity is sold. Let each man take due earnings, then, And keep his hands from holy things, And from blasphemy stand apart— Else the crackling blast of heaven Blows on his head, and on his desperate heart; Through fools will honor impious men, In their cities no tragic poet sings. Summarize this stanza. How would you describe the tone? Shall we lose faith in Delphi’s obscurities, We who have heard the world’s core Discredited, and the sacred wood Of Zeus at Elis praised no more? The deeds and the strange prophecies Must make a pattern yet to be understood. Zeus, if indeed you are lord of all, Throned in light over night and day, Mirror this in your endless mind: Our masters call the oracle Words on the wind, and the Delphic vision blind! Their hearts no longer know Apollo, And reverence for the gods has died away. Summarize this stanza. How would you describe the tone? 12 Directions: Answer all questions in full and complete sentences. You need to include a direct quotation in at least TWO of your responses per section. Scene 3: 1. What news brings the messenger to Thebes? 2. Why are the Thebans so happy about the news? 3. Why doesn’t Oedipus feel relieved? 4. Why does Iocaste start to hesitate about the investigation? What does she say to try and stop it? 5. Why does Oedipus think she is hesitating? 6. Cite an example of dramatic irony from Oedipus’ last speech and explain it. 13 Directions: Answer all questions in full and complete sentences. You need to include a direct quotation in at least TWO of your responses per section. Scene 4: 1. How does Oedipus know that he can trust the shepherd? 2. Why does the shepherd tell the messenger to stop talking? What does the shepherd know that the messenger does not? 3. Why did the shepherd give the baby away? 4. What is Oedipus’ reaction to the news? 14 Directions: Answer all questions in full and complete sentences. You need to include a direct quotation in at least TWO of your responses per section. Ode IV 1. What has Oedipus just found out about in Scene IV? 2. How does the chorus feel about this discovery? Quote from the text to support your opinion. 3. How does the chorus feel about Oedipus? Quote from the text to support your opinion. 4. How has the opinion of the chorus about Oedipus changed over the course of the play? Quote from the text to support your observations. 15 Directions: Answer all questions in full and complete sentences. You need to include a direct quotation in at least TWO of your responses per section. Exodos: 1. How does Iocaste die? 2. What did Oedipus do following Iocaste’s death? What figurative language is used to describe his actions? 3. How does Oedipus explain his decision to harm himself? 4. What is ironic about Creon’s rise to the throne? 5. What does Oedipus think will happen to his daughters? 6. What is Choragos’ final advice? What does it mean? 16 Elements of Literature: Tragedy and the Tragic Hero from World Literature: Revised Edition: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-­‐322 B.C.) pays special attention to tragedy in his treatise The Poetics. He explains that tragic dramas should be tightly unified constructions based on a single action and featuring a single protagonist, or hero. Tragedies generally deal with characters who are neither exceptionally virtuous nor exceptionally evil. According to Aristotle, the hero should have “a character between these two extremes—that of a man [or a woman] who is not preeminently good or just, yet whose misfortune is brought about not by vice or depravity, but by some error in judgment or frailty.” This weakness is known as hamartia, which is often translated as “tragic flaw.” Typically, this flaw often takes the form of excessive pride or arrogance, called hubris. As a tragedy unfolds, according to Aristotle, the tragic hero goes through one or more reversals of fortune leading up to a final recognition of a truth that has remained hidden from him. In the process he experiences a profound suffering. Aristotle supplements his theory by observing that, as the members of an audience witness this deep suffering, their emotions of pity and fear lead them to experience a feeling of catharsis, or purgation, that leaves them with a new sense of self-­‐awareness and renewal. Paradoxically, then, the experience of watching a tragedy and being purged of upsetting emotions brings a kind of pleasure to the spectator. In his analysis of tragedy in The Poetics, Aristotle cites Sophocles’ play Oedipus Rex several times as a supreme example of tragic drama. Were you moved to pity and fear by this tale of Oedipus’s suffering? Did you also feel a sense of renewal through the experience? 1. Did “the experience of watching a tragedy and being purged of upsetting emotions [bring] a kind of pleasure to the spectator”—you? Explain why or why not. 2. Think about some of the “modern tragic heroes” we have discussed. How did you feel when you hear news of their downfalls? Give specific examples in your answer. 17 A Critical Comment: Themes in Oedipus Rex from World Literature: Revised Edition: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston Many readers have wondered about the theme or message that Oedipus intended to convey in Oedipus Rex. Some critics say that the play is nothing more than an ingenious detective story, in which the detective himself turns out to be the hated culprit. Others assume that the play must mask hidden references to Sophocles’ own time, so that Oedipus’s pride and downfall mirror the figure of the proud statesman Pericles, or perhaps the fortunes of Athens itself. While each of these theories may represent part of the truth, many readers have recognized that the implications of the tragedy go far beyond its structure as a detective story or its relevance to real life in the playwright’s own time. One of the main questions of the drama has to do with the degree of guilt to be assigned to the fallen king. In one view, Oedipus must be held fully responsible for his actions. Even if his monumental crimes were committed unintentionally, critics say, Oedipus might have avoided them through greater vigilance. Others insist that the very process of discovery shows the great kings tragic flaw: his own self-­‐confidence and pride as revealed in his arrogant treatment of Teiresias and Creon. The actual Greek title of the play is, in fact, Oedipus Tyrannos (the title Oedipus Rex is Latin for “Oedipus the King”). The term tyrant in ancient Greek refers more to a powerful, self-­‐made ruler than to an evil despot, and Oedipus, as portrayed by Sophocles, does not seem particularly tyrannical. Still, the flaw of pride in Oedipus cannot be lightly dismissed. One the other hand, we also see from numerous touches of characterization in the play that Oedipus is basically a sincere ruler, a good man, and a loving father. We are therefore forced to consider even larger questions of divine justice and the individual’s place in the world. Are human beings creatures of free will, or are their actions, for good or ill, determined by forces beyond their control? In interpreting this play, it is difficult to say exactly where Sophocles stands on this issue. Certainly we can hear the faith and reverence for the gods reflected in most of the choral odes. On the other hand, Sophocles also carefully removes any direct divine intervention from the action of the play itself. Moreover, he allows Oedipus and Iocaste to serve occasionally as spokespersons for the religious skepticism that was in the air in Athens during the later fifth century B.C. At several points in the play, Oedipus defines himself as a “child of luck,” also suggesting a denial of the power of the gods. In the final moments of the drama, this issue emerges in a new light. Throughout the play, the idea that the individual is a completely self-­‐sufficient character is undermined by irony and doubt. But in the end, it is Oedipus’s self-­‐knowledge, in fulfillment of the injunction to “know thyself,” that gives him the strength to face the truth and go out and meet his fate. 18 The New York Times, November 20, 2007 Denial Makes the World Go Round By BENEDICT CAREY For years she hid the credit card bills from her husband: The $2,500 embroidered coat from Neiman Marcus. The $900 beaded scarf from Blake in Chicago. A $600 pair of Dries van Noten boots. All beautiful items, and all perfectly affordable if she had been a hedge fund manager or a Google executive. Friends at first dropped hints to go easy or rechannel her creative instincts. Her mother grew concerned enough to ask pointed questions. But sales clerks kept calling with early tips on the coming season’s fashions, and the seasons kept changing. “It got so bad I would sit up suddenly at night and wonder if I was going to slip up and this whole thing would explode,” said the secretive shopper, Katharine Farrington, 46, a freelance film writer living in Washington, who is now free of debt. “I don’t know how I could have been in denial about it for so long. I guess I was optimistic I could pay, and that I wasn’t hurting anyone. “Well, of course that wasn’t true.” Everyone is in denial about something; just try denying it and watch friends make a list. For Freud, denial was a defense against external realities that threaten the ego, and many psychologists today would argue that it can be a protective defense in the face of unbearable news, like a cancer diagnosis. In the modern vernacular, to say someone is “in denial” is to deliver a savage combination punch: one shot to the belly for the cheating or drinking or bad behavior, and another slap to the head for the cowardly self-deception of pretending it’s not a problem. Yet recent studies from fields as diverse as psychology and anthropology suggest that the ability to look the other way, while potentially destructive, is also critically important to forming and nourishing close relationships. The psychological tricks that people use to ignore a festering problem in their own households are the same ones that they need to live with everyday human dishonesty and betrayal, their own and others’. And it is these highly evolved abilities, research suggests, that provide the foundation for that most disarming of all human invitations, forgiveness. In this emerging view, social scientists see denial on a broader spectrum — from benign inattention to passive acknowledgment to full-blown, willful blindness — on the part of couples, social groups and organizations, as well as individuals. Seeing denial in this way, some scientists argue, helps clarify when it is wise to manage a difficult person or personal situation, and when it threatens to become a kind of infectious silent trance that can make hypocrites of otherwise forthright people. “The closer you look, the more clearly you see that denial is part of the uneasy bargain we strike to be social creatures,” said Michael McCullough, a psychologist at the University of Miami and the author of the coming book “Beyond Revenge: The Evolution of the Forgiveness Instinct.” “We really do want to be moral people, but the fact is that we cut corners to get individual 19 advantage, and we rely on the room that denial gives us to get by, to wiggle out of speeding tickets, and to forgive others for doing the same.” The capacity for denial appears to have evolved in part to offset early humans’ hypersensitivity to violations of trust. In small kin groups, identifying liars and two-faced cheats was a matter of survival. A few bad rumors could mean a loss of status or even expulsion from the group, a death sentence. In a series of recent studies, a team of researchers led by Peter H. Kim of the University of Southern California and Donald L. Ferrin of the University of Buffalo, now at Singapore Management University, had groups of business students rate the trustworthiness of a job applicant after learning that the person had committed an infraction at a previous job. Participants watched a film of a job interview in which the applicant was confronted with the problem and either denied or apologized for it. If the infraction was described as a mistake and the applicant apologized, viewers gave him the benefit of the doubt and said they would trust him with job responsibilities. But if the infraction was described as fraud and the person apologized, viewers’ trust evaporated — and even having evidence that he had been cleared of misconduct did not entirely restore that trust. “We concluded there is this skewed incentive system,” Dr. Kim said. “If you are guilty of an integrity-based violation and you apologize, that hurts you more than if you are dishonest and deny it.” The system is skewed precisely because the people we rely on and value are imperfect, like everyone else, and not nearly as moral or trustworthy as they expect others to be. If evidence of this weren’t abundant enough in everyday life, it came through sharply in a recent study led by Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dr. Ariely and two colleagues, Nina Mazar and On Amir, had 326 students take a multiplechoice general knowledge test, promising them payment for every correct answer. The students were instructed to transfer their answers, for the official tally, onto a form with color-in bubbles for each numbered question. But some of the students had the opportunity to cheat: they received bubble sheets with the correct answers seemingly inadvertently shaded in gray. Compared with the others, they changed about 20 percent of their answers, and a follow-up study demonstrated that they were unaware of the magnitude of their dishonesty. “What we concluded is that good people can be dishonest up to the level where conscience kicks in,” said Dr. Ariely, author of the book “Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions,” due out next year. “That essentially you can fool the conscience a little bit and make small transgressions without waking it up. It all goes under the radar because you are not paying that much attention.” It is a mistake to underestimate the power of simple attention. People can be acutely aware of what they pay attention to and remarkably blind to what they do not, psychologists have found. In real life, to be sure, casual denials of bad behavior require more than simple mental gymnastics, but inattention is a basic first ingredient. 20 The second ingredient, or second level, is passive acknowledgment, when infractions are too persistent to go unnoticed. People have adapted a multitude of ways to handle such problems indirectly. A raised eyebrow, a half smile or a nod can signal both “I saw that” and “I’ll let this one pass.” The acknowledgment is passive for good reasons: an open confrontation, with a loved one or oneself, risks a major rupture or life change that could be more dire than the offense. And more often than is assumed, a subtle gesture can be enough of a warning to trigger a change in behavior, even one’s own. In an effort to calculate exactly how often people overlook or punish infractions within their peer groups, a team of anthropologists from New Mexico and Vancouver ran a simulation of a game to measure levels of cooperation. In this one-on-one game, players decide whether to contribute to a shared investment pool, and they can cut off their partner if they believe that player’s contributions are too meager. The researchers found that once players had an established relationship of trust based on many interactions — once, in effect, the two joined the same clique — they were willing to overlook four or five selfish violations in a row without cutting a friend off. They cut strangers off after a single violation. Using a computer program, the anthropologists ran out the simulation over many generations, in effect speeding up the tape of evolution for this society of players. And the rate of overlooking trust violations held up; that is, this pattern of forgiving behavior defined stable groups that maximized the survival and evolutionary fitness of the individuals. “There are lots of way to think about this,” said the lead author, Daniel J. Hruschka of the Santa Fe Institute, a research group that focuses on complex systems. “One is that you’re moving and you really need help, but your friend doesn’t return your call. Well, maybe he’s out of town, and it’s not a defection at all. The ability to overlook or forgive is a way to overcome these vicissitudes of everyday life.” Nowhere do people use denial skills to greater effect than with a spouse or partner. In a series of studies, Sandra Murray of the University of Buffalo and John Holmes of the University of Waterloo in Ontario have shown that people often idealize their partners, overestimating their strengths and playing down their flaws. This typically involves a blend of denial and touch-up work — seeing jealousy as passion, for instance, or stubbornness as a strong sense of right and wrong. But the studies have found that partners who idealize each other in this way are more likely to stay together and to report being satisfied in the relationship than those who do not. “The evidence suggests that if you see the other person in this idealized way, and treat them accordingly, they begin to see themselves that way, too,” Dr. Murray said. “It draws out these more positive behaviors.” Faced with the high odor of real perfidy, people unwilling to risk a break skew their perception of reality much more purposefully. One common way to do this is to recast clear moral breaches as foul-ups, stumbles or lapses in competence — because those are more tolerable, said Dr. Kim, of U.S.C. In effect, Dr. Kim said, people “reframe the ethical violation as a competence violation.” 21 She wasn’t cheating on him — she strayed. He didn’t hide the losses in the subprime mortgage unit for years — he miscalculated. This active recasting of events, built on the same smaller-bore psychological tools of inattention and passive acknowledgment, is the point at which relationship repair can begin to shade into willful self-deception of the kind that takes on a life of its own. Everyone knows what this looks like: You can’t talk about the affair, and you can’t talk about not talking about it. Soon, you can’t talk about any subject that’s remotely related to it. And the unstated social expectations out in the world often reinforce the conspiracy, no matter its source, said Eviatar Zerubavel, a sociologist at Rutgers and the author of “The Elephant in the Room: Silence and Denial in Everyday Life.” “Tact, decorum, politeness, taboo — they all limit what can be said in social domains,” he said. “I have never seen tact and taboo discussed in the same context, but one is just a hard version of the other, and it’s not clear where people draw the line between their private concerns and these social limits.” In short, social mores often work to shrink the space in which a conspiracy of silence can be broken: not at work, not out here in public, not around the dinner table, not here. It takes an outside crisis to break the denial, and no one needs a psychological study to know how that ends. In Ms. Farrington’s case, the event was a move out of the country for her husband’s job. Unable to earn much money from her own work, she kept buying but had no way to cover the credit card payments. “Basically,” she said, “I had to fess up. It was terrible, but I fessed up to my husband, I fessed up to my mother and to another friend who was getting the bills while I was away. This whole web of intrigue, and in the end it just had to crash.” She now hunts for better bargains on eBay. 22 Motif Essay It’s time to synthesize your ideas about a motif of your choosing. The steps (separate deadlines & graphic organizer) below are designed to help you create a successful and argumentative 3-­‐4-­‐paragraph essay. The Questions/Question: How does the development of a motif contribute to meaning in a text? How does an author show human nature through this development? To complete our unit on Oedipus Rex and motifs, you will complete an essay that answers the question: How does the development of a motif contribute to a theme in Oedipus Rex? Requirements: Your paper should: • be typed in Times New Roman or a like font • be double spaced • be three or 4 paragraphs in length • have standard 1-­‐1.25” margins • have an original title • Include four quotations, all on one motif. • Properly embed quotations in your original writing • Write in the present tense (all literature happens as we read it) • Write in the third person (no I, we, or you) Due Dates 6-8 quotations on sticky notes: ____________________ Timeline graphic organizer: ______________________ Rough draft (for peer review): ____________________ Final draft (submitted on Turnitin): _______________ 23