39_47 prospectus liability for PDF.qxd

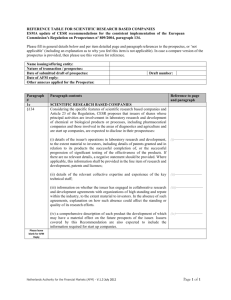

advertisement

FEATURE PLC PRACTICAL LAW COMPANY Global Counsel PLC Prospectus liability in Europe and the US Understanding the issues Illustration: Getty Images www.practicallaw.com/A32108 Depending on the jurisdiction, liability for misstatements in offering documents and other financial statements can fall on any number of entities, including the issuing company and its directors and officers. Julian COPEMAN, Alex BAFI, Denis CHEMLA and Bettina FRIEDRICH examine when such liability arises in Europe and the US, and outline the remedies available for breach. Shareholder activism is on the rise. Particularly in the US, shareholders are becoming increasingly aware of their rights as investors, and are acting to protect those rights. For instance, securities class actions are on the increase in the US, with 224 suits filed in 2002, a rise of 31% over the previous year (research conducted by Stanford Law School, see http://securities.stanford.edu/litigation_activity.html). While litigation on this scale is not yet taking place in Europe, it is nev- THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. 39 CORPORATE: PROSPECTUS LIABILITY ertheless essential that companies be aware of the ways in which they and their directors and officers can be held liable for misstatements in offering documents and other financial statements. This article addresses the following issues to be considered regarding such liability in relation to France, Germany, the UK (England and Wales) and the US: • Who may be liable for misstatements. • The types of statements that may give rise to liability. • How a plaintiff can establish liability and the remedies that are available for breach. • Any other issues regarding liability that may arise. France In France, it is a criminal offence to make misrepresentations in offering documents. The criminal courts have jurisdiction to deal with the civil consequences of such misrepresentations. In order to obtain damages, victims usually participate in criminal proceedings brought by the Public Prosecutor, or commence criminal proceedings in their own right, although civil damages claims are also possible. Who may be liable Any person is prohibited from spreading, by any means, false or misleading information related to the future prospects or actual state of a company listed on a regulated market, or to the future prospects of a security listed on a regulated market, if this information is likely to have an influence on its price (article L.465-1 S4, Financial and Monetary Code (FMC)). “Any person” is extremely wide and includes: • Issuers. Where officers act on behalf of their company, the company itself is liable, but this does not exclude the liability of its officers, and both may be prosecuted. Thus directors and officers of the issuer are included. Statutory auditors and shareholders may also be included. 40 • Persons with no direct link to the issuer, such as journalists, financial analysts, advisers, financial intermediaries, banks or competitor companies. In fact there is no limit to who can be prosecuted as the author of false or misleading information so long as it is shown that he was aware of the fact that the information disclosed to the public was false or misleading. Types of statements There is no limit to the type of document in which false or misleading information may be communicated to the public. Case law gives examples of prospectuses, commercial advertisements, and communications to the general assembly of shareholders, as well as publication of balance sheets, press articles, press releases and statements at press conferences. Establishing liability and remedies It is becoming increasingly common for investors to bring both civil and criminal proceedings, as recent case law has improved victims’ ability to recover damages by way of civil actions. Administrative authorities also have specific powers to punish offenders. Criminal liability. Criminal liability arises where the false or misleading information given concerns the future prospects or the actual financial situation of the issuer, and must be sufficiently specific. Mere rumours do not trigger criminal liability, but incomplete information may be treated as false information. Examples of what has been held to be “false or misleading information” include: a press release stating that the issuer was about to improve its financial situation; and false indications in a prospectus relating to a capital increase. the information in fact caused any damage. However, a civil victim claiming in a criminal proceeding (constitution de partie civil) must show a causal link between the false information and his losses in order to obtain damages. Criminal penalties can be high, and include up to two years’ imprisonment as well as fines of up to EUR1.5 million (about US$1.72 million). Where a profit was made as a result of the misleading information, the fine cannot be less than EUR1.5 million, and may be up to ten times this amount. A convicted company can be fined five times more than an individual. An action is time-barred three years from the date on which the information became public knowledge. Civil liability. An investor can take civil action to: • Have a sale of securities declared null, if he can show that the issuer itself wilfully misled investors in order to encourage them to acquire securities. To succeed, the investor must show that: - in the absence of the misrepresentation, he would not have bought the securities; and - that the officers of the issuer acted on behalf of the issuer, which benefited from their misbehaviour. This type of action is subject to a time bar of five years from the date the misrepresentation was discovered. • Claim damages from any person who published misleading information. The investor must show: One important limit to the scope of criminal liability is that a failure to correct another’s false information is not an offence (article L. 465-1, FMC). - wrongful conduct of the same kind as in a criminal proceeding; and For a successful prosecution, the false or misleading information must have been capable of influencing prices, but the actual consequences of the false information are not relevant, and it is not necessary to show that A claim of this type is time-barred ten years from the date the damage occurred. - that the false or misleading statement caused the damages claimed. Administrative liability. A regulation issued by the administrative author- THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. CORPORATE: PROSPECTUS LIABILITY ity in charge of regulating and supervising the markets, the Commission des Operations de Bourse (COB), contains provisions similar to article L. 465-1 of the FMC (Regulation n° 98-07). However, the scope of the regulation is even wider as issuers are under a permanent obligation to disclose any information likely to affect prices. As a result, remaining silent or not correcting false or outdated information amounts to a breach of the regulation. The COB can effectively suspend a listing where it considers that the market has not been correctly informed. It must call the state public attorney’s attention to any fact likely to give rise to criminal liability. Administrative authorities (including the COB) can impose sanctions of an amount equal to the fine set by article L.465-1 (see Criminal liability above). Indeed, the same breach can give rise to both administrative and criminal sanctions (that is, fines under administrative and criminal law). Disciplinary measures are also available, ranging from a mere warning to the withdrawal of a licence. Other issues The calculation of damages by way of compensation is currently uncertain. In 1993, the French Supreme Court decided that investors could recover damages corresponding to the difference between the price paid to acquire shares in reliance on false information and the real value of those shares at the time of purchase (Cass. Crim. 15 March 1993, Bull. Crim. no. 113, p280). Subsequent decisions of lower courts have, however, been more favourable to investors, allowing the total amount actually paid for the shares, and case law is therefore not settled. Germany Since the 1980s, the civil courts have dealt with a number of spectacular cases regarding offering documents, such as Beton & Monierbau (BGH vom 26.3.1984 – II ZR 171/83 – BGHZ 90, 381), Sachsenmilch (BGH vom 9.2.1998 – II ZR 278/96 – NJW 1998, 2054) and Elsflether Werft (BGH vom 14.7.1998 – XI ZR 173/97 – BGHZ 139, 2) and have developed general civil law principles for prospectus liability. There is also statutory liability for prospectuses of marketable securities that are incomplete or incorrect (sections 44 to 49, Stock Exchange Act (Börsengesetz) (BörsG)). Civil case law actions differ from statutory prospectus liability actions. Who may be liable Liability for statements in a published prospectus attaches differently depending on the purpose for which the prospectus was published: • Liability is imposed on those who assumed responsibility for the prospectus and on persons who initiated the issuance of the prospectus (section 44, BörsG). The issuer and the financial institution applying for the listing of the issuer and participating in the distribution of the shares must sign the listing prospectus and are liable for materially misleading facts in, and omissions from, prospectuses and other public statements. • The issuer’s directors and officers, auditors and lawyers generally do not assume responsibility for the prospectus and are not deemed to initiate the issuance of a prospectus (sections 44 and 45, BörsG). They may, however, be liable under general principles of civil law for knowingly suppressing or recklessly disregarding material omissions or misstatements. • Control persons. The legislation is intended in particular to cover parties who have an economic interest in the listing and, as a result, in the issuance of the prospectus. • Any person who appeared “in charge of the investment” (founders, managers, those who exercised directly or indirectly a significant influence during the preparation of the prospectus, auditing firms and lawyers) may be liable under general principles of civil tort. A person who causes damages to another person by committing offences such as fraud or investment fraud can be held generally liable (section 823(2), Civil Code (BGB)). A person who wilfully and intentionally causes damage to another in violation of public policy can also be liable (section 826, BGB). Types of statements The following types of statements can give rise to liability: • Prospectuses. BörsG regulations apply to listing prospectuses for trading on the official market and other written statements that are not prospectuses (section 44), business reports for listing on the regulated market (section 77) and sales prospectuses prepared for public offerings (section 13, Sales Prospectus Act (Verkaufsprospektgesetz) (VerkProspG)). For the purposes of the BörsG, the term “prospectus” relates to written material, prepared for the relevant purpose. Statutory liability does not apply to any other public ad hoc statements, announcements or publications. • Other public statements. The term “prospectus” has a broader meaning under case law, including any written material that is related to the marketing of the investment opportunity at issue (for example, letters or advertisements). Establishing liability and remedies The elements of a civil law action for damages due to incomplete or incorrect offering material differ from statutory prospectus liability claims. Statutory liability. To prove statutory liability the investor must establish: • That the prospectus was incorrect or incomplete in a material aspect; and • That he acquired the respective securities after the publication of the prospectus. No showing of scienter (some intent to defraud or manipulate) or causation is required. Whether a fact is considered material depends on the circumstances of the specific case and must be judged from the view of “an average person who is able to comprehend the information contained in a prospectus if he reads it THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. 41 CORPORATE: PROSPECTUS LIABILITY Prospectus liability: who can be liable for what France To whom may liability attach? Anyone spreading false or misleading information that may influence the price of a listed security, which may include: • Issuers, their directors and officers and in some cases statutory auditors and shareholders. • Those with no direct link to the issuer, such as, for example, advisers, financial intermediaries, banks or competitor companies. • The issuer and the financial institution applying for the listing. • The issuer's directors and officers, auditors and lawyers. • "Control persons" with an economic interest in the listing. • Any person who appeared "in charge of the investment". What types of statements may give rise to liability? There is no limit to the type of document that may give rise to liability. For example, liability may arise from statements made in prospectuses, commercial advertisements and communications to the general assembly of shareholders. • Listing prospectuses for trading on the official market, written statements that are not prospectuses, business reports for listing on the regulated market and sales prospectuses prepared for public offerings (statutory liability). • Other public statements such as letters or advertisements (case law claims). Does the investor have to show causation/reliance? Must show a causal link between the false information and the loss. • No, in a statutory claim. • Yes, in a case law claim. Can a purchaser in the after market claim on the basis of a prospectus? Yes, subject to the causal link. For 12 months, statute assumes that the purchase was made on the basis of the "investment atmosphere" created by the prospectus. thoroughly, is able to understand the information contained in a balance sheet but not having further knowledge or education” (BGH vom 12.7.1982 – II ZR 175/81 – NJW 1982, 2823 (2824)). The German Supreme Court (BGH) has held that prospectus liability can also be based on opinions and projections unless reasonably made and based on sufficiently hard information (BGH vom 12.7.1982 – II ZR 175/81 NJW 1982, 2823 (2824); vgl. Auch Assmann/Lenz/Ritz, Verkaufsprospektgesetz S 13 Rd. 31 f). Even if the details are correct, a 42 Germany prospectus may be considered incorrect if the overall picture of a company appears in a more favourable light than in reality, the standard being the “true overall picture test”. ciples and/or tort. A plaintiff bringing a claim under principles of general case law bears a heavier burden. He must demonstrate each of the following elements: The investor does not need to establish that he relied on the offering document to invest. He must establish that he suffered losses, without further establishing that the losses were caused by the omitted information. • The defendant knew or should have known that the prospectus contained inaccurate or incomplete information, or, alternatively, that the defendant acted with intent to cause damage to the investor. Liability under general civil law prin- • The investor relied on the information. THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. CORPORATE: PROSPECTUS LIABILITY Other issues The following issues regarding liability may arise: UK US • Issuers. • Directors. • Those who accept and are stated in the particulars as accepting responsibility for, or who authorised the contents of, the particulars. For example, sponsors, experts, underwriters and professional advisers. • Issuers. • Underwriters, other professional advisers and experts. • Directors, officers and principal shareholders. • "Control persons" with power to direct the management or policies of others directly liable for the disclosure. • Listing particulars and prospectuses (statutory claim). • Documents on the basis of which investment decisions will be made, or where the maker owes a duty of care to the recipient, for example, listing particulars, prospectuses, general corporate announcements and accounts. • Registration statements (section 11, Securities Act). • Prospectuses (section 12(a)(2), Securities Act). • Other public statements, such as press releases and financial reports (Rule 10b-5, Exchange Act). • Yes, in a common law claim. • An FSMA claim requires loss to be suffered as a result of the misleading statement or omission, but query how this must be proved in practice? • No, in a claim under section 11 or section 12 (a)(2) (but defendant may show absence of causation). • Yes, in a 10b-5 claim, although courts will presume reliance if the misstatement is material and the securities are traded on an established market. • Yes, in an FSMA claim, but query for how long? • No, in a misrepresentation claim. • Arguable in a negligent misstatement claim. Yes. • The reliance on the misstatement or omission caused the investor’s loss. Investor claims based on general principles of civil law are comparatively rare and only under very specific circumstances based on these sources of liability. In addition, class actions cannot be brought. Criminal offences. Any person (issuer’s directors, officers or accountants auditing the issuer’s financial statements) who wilfully makes in- correct favourable statements or conceals unfavourable information in a prospectus which is relevant to an investment decision will be punished by fines or imprisonment (section 264a, Criminal Code (StGB)). If someone is convicted for violating his professional duties, the court can prohibit him temporarily or permanently from engaging in his profession or trade (section 70a, StGB). Investors cannot attempt to obtain restitution for losses in a criminal trial or via an administrative procedure. • Negligence and standard of care. In statutory liability claims for an incorrect or incomplete prospectus, only gross negligence triggers liability. This entails showing that the defendant knew of the problem and failed to rectify it. The burden is on the defendant to prove that he was not grossly negligent. In a civil case law claim, the normal standard of negligence applies. The investor need only show that the issuer knew or should have known that the prospectus was incorrect or incomplete or that the information he provided was incorrect. • Causation. Causation is not problematic in statutory liability claims. For a 12-month period after the initial issue of the securities it is assumed by statute that any purchase of the securities is on the basis of the prospectus (or the “investment atmosphere” created by the prospectus). It is for the defendant to prove that the prospectus was in fact irrelevant to the investment decision. This is difficult, but may be possible if the defendant can demonstrate that the “investment atmosphere” ended before the investment with the publication of information updating the information contained in the prospectus (such as annual or quarterly reports, ad hoc reports, massive stock loss or insolvency). By contrast, in a civil law claim the investor must prove that he reviewed the offering document and that the investment decision was based on that document. Both statutory and civil case law claims will fail if the defendant can show that the investor knew the prospectus was wrong or misleading, but still purchased the securities. • Calculation of damages. In statutory liability claims, the investor is entitled to reimbursement of the purchase price to the extent that this does not exceed the initial issue price, as well as the “usual costs” related to such an acquisition. The investor must return the shares. In civil law claims, the investor is entitled to full damages, including interest and dividend payments that he would have received. THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. 43 CORPORATE: PROSPECTUS LIABILITY • Time limits. Statutory claims are time-barred 12 months from the date that the purchaser was made aware of the incorrect or incomplete particulars, and in any event three years after the prospectus was published. UK The publication in the UK (England and Wales) of offering documents exposes those responsible for their preparation and publication to potential liability for misrepresentation or negligent misstatement. Potentially simpler statutory liabilities arise under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), previously contained in the Financial Services Act 1986. Criminal liability may also arise, as well as liabilities under the Listing Rules or other selfregulatory schemes. In practice, without clear evidence of fraud, such claims are not clear cut, and may face complex issues, particularly in relation to causation and reliance, in showing that the misleading information in fact caused the damage, or that the investor in fact relied on the misleading information in entering into the investment. This is presumably why few cases have reached trial in recent years. Faced with technical difficulties on one side, and publicity issues on the other, claims usually settle long before trial. Who may be liable Liability may attach as follows: • Issuers are always subject to liability for misleading or false statements in offering documents. • Directors must sign a confirmation letter in relation to prospectuses that all information required by the FSMA is included. They may therefore be liable. • Those who accept and are stated in the particulars as accepting responsibility for, or who authorised the contents of, the particulars are subject to statutory liability. This may include sponsors, experts, underwriters and professional advisers. 44 • Documents on the basis of which investment decisions will be made, such as listing particulars, prospectuses, pathfinders, offering memoranda and circulars. their professional advisers would reasonably require or expect to find in listing particulars for the purpose of making an informed assessment of the company and of the rights attaching to the securities to be listed. This is an ongoing duty, which may require submission of supplementary listing particulars. • General corporate announcements, accounts and other financial statements. The investor has a right to seek compensation from the responsible person where he has (section 90, FSMA): Establishing liability and remedies Liability of the following types may arise: • Acquired the securities which are the subject of the particulars; and Types of statements Liability can arise in relation to the following types of statements: • Statutory liability claims can be brought in relation to listing particulars and prospectuses. • Liability in misrepresentation or misstatement for incorrect information may arise in relation to the publication of documents detailing a company’s performance, changes in the structure of a company, or fund raising, either where the document is intended to induce an investor to purchase securities or where the maker owes a duty of care to the recipient. In addition, criminal liability may arise under the FSMA or the Theft Act 1968 for behaviour such as: • Knowingly or recklessly making a misleading or false statement or forecast in a listing particular. • Dishonestly concealing any material facts. • Creating a false or misleading impression as to the market in or value of an investment intending to induce, and inducing, someone to subscribe for or underwrite that investment. Statutory liability. The FSMA, backed up by the Listing Rules, imposes disclosure duties on those responsible for listing particulars. This includes all information within the knowledge of responsible persons, or which it would be reasonable for them to obtain, which investors and • Suffered loss in respect of those securities as a result of any untrue or misleading statement, or as a result of the omission of any matter required by the FSMA to be included in the statement. An investor can also claim compensation where he acquired relevant securities and suffered loss as a result of a failure by the issuer to submit supplementary listing particulars when required. A claimant must have acquired the relevant securities. This includes a person who has contracted to acquire the securities or an interest in them (section 90(7), FSMA). This covers owners of shares held through a nominee, but leaves open note holders. In the case of notes, the registered holders will be settlement systems such as Euroclear and Cedel with individual investors holding securities via account holders there. The investor does not hold specific notes, but has an interest in the relevant part of a whole issue. It is unclear whether a noteholder would, therefore, have title to sue for compensation under the FSMA. The FSMA compensation claim is available to purchasers in the after market (Lightman J, obiter, in Possfund Custodian Trustee Limited v. Diamond [1996] 2 All ER 774). Misrepresentation. Where there is a material misrepresentation of fact in an offering document on which a purchaser relied, which was inaccurate, and which caused the purchaser loss, THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. CORPORATE: PROSPECTUS LIABILITY the purchaser can seek rescission or damages. A statement of opinion is not actionable unless it can be said to be a statement of fact. Since FSMA duties of disclosure do not apply to such a claim, a claim for omission is only possible if the omission can be shown to make the remaining text inaccurate and misleading. Related information This PLCGlobal Counsel article can be found on PLCGlobal Counsel Web at www.practicallaw.com/A32108. The following information can also be found on www.practicallaw.com: Know-how topics Securities markets and regulation www.practicallaw.com/T889 A claim in misrepresentation is limited to the initial purchaser because a prospectus, issued with a view to inducing people to purchase the securities, is actionable only by those who were so induced at the time of the issue. Dispute resolution and litigation www.practicallaw.com/T69 Rescission of the contract may be possible, leading to the return of the purchaser’s original investment, but not where there is any delay or where circumstances change, such as a sale of the shares. Otherwise damages are available, being the difference between the price of the securities and their “true” value at the time of the purchase if the misrepresentation had not been made (not if the misrepresentation had been true). Negligent misstatement. If the investor can show that there was a misstatement by the maker of a statement in the offering document who owed him a duty of care, the investor can claim in negligence (Hedley Byrne v. Heller [1964] AC 465). This point has not been tested in relation to public issues. Given that the FSMA remedies do not require proof of negligence, investors will, where possible, sue under the FSMA rather than in negligence. However, a negligence claim might be available against a wider group than those treated as being responsible for the particulars under the FSMA. In order to establish the duty of care, a claimant must show foreseeability of damage, and proximity of relationship between the claimant and defendant. This means considering: • The purpose for which the statement was made. • The defendant’s knowledge. • The reasonableness claimant’s reliance. of the Handbooks Dispute resolution www.practicallaw.com/disputehandbook Articles Responding to shareholder activism www.practicallaw.com/A24160 Certification of financial reports: applying the new requirements www.practicallaw.com/A26882 Class actions www.practicallaw.com/A21592 His master’s voice: shareholder activism set to increase www.practicallaw.com/A26750 Practice notes Verification: rights issues Misleading statements and market manipulation The claimant must also show that it is reasonable to impose a duty of care. Given the difficulty in establishing a duty of care in relation to an unascertained class of people, it is thought that no duty of care is owed to after market purchasers (Al Nakib v. Longcroft [1990] 3 All ER 321), although it has since been held to be arguable in a case where a purchaser showed that the prospectus had also been intended informally to encourage after market investors (Possfund, supra). Other issues In all claims, the claimant must prove causation, that is, that the loss was caused by the breach. In the case of a claim under the FSMA, the loss must be suffered “as a result of” the untrue or misleading statement or omission (section 90). The precise test of causation is unclear. Loss is not suffered directly as a result of a misleading statement or omission, but the misstatement or omission may influence the decision to purchase or the price. If, as with a misrepresentation claim, causation were based on the state- www.practicallaw.com/A2922 www.practicallaw.com/A20710 ment influencing the decision to purchase, then it would seem that the investor would need to show that he read and relied on the particulars. This would not reflect the way in which the market operates, and would reduce the availability of a statutory compensation claim. This point has not been tested in the courts, but under the old section 67 of the Companies Act 1985, a claimant had to show that he had bought securities on the face of the prospectus and had suffered loss by reason of an untrue statement included in it. In the FSMA the wording appears to be deliberately wider. It may, therefore, be that the claimant must simply show that the market and the price of securities were affected by the misleading statement, and that his reliance on that caused his loss. Causation becomes more problematic for purchasers in the after market (who can claim under the FSMA, and possibly in negligence, but not in misrepresentation). An after market purchaser needs to show that the misleading statement in the particulars still influenced the market when he bought. Clearly the particulars cannot have an indefinite effect. There is THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. 45 CORPORATE: PROSPECTUS LIABILITY no statutory presumption that a prospectus is effective for a particular period of time after publication, but presumably the court would seek to answer the factual question of when the listing particulars can be said to have been superseded. Subsequent publication of annual or interim accounts would make it difficult for a claimant to assert that he had relied on earlier listing particulars, since the market’s perception of the value of the securities would have been influenced by publication of more up-todate financial information. US Many on Wall Street believe the growth in securities claims in the US is driven by plaintiffs’ law firms, which depend on the substantial fees reaped from these claims. Investors’ lawyers take most of these class action cases on a contingency fee basis, and generally receive up to 33% of any recovery. Although a 1995 law made it more difficult for plaintiffs to initiate spurious suits at the first sign of a drop in stock prices, declining markets have proven a boon to securities class action lawsuits. In addition to the economic climate, several other factors make litigation generally far more attractive in the US than in Europe: • Mass litigation class actions are a practical means of representing investor interests under federal law. • US courts refrain from punishing defeated plaintiffs with defendants’ legal fees. • The role of US juries in determining materiality often pushes deeppocket corporate defendants into settlement negotiations. Settlement amounts may also be on the rise. The gamble of a jury trial and the expense of discovery have long made pre-trial settlement an attractive option for companies under fire. In class action lawsuits, settlement amounts are generally higher when the suits are accompanied by SEC investigations, an increasingly common phenomenon post-Enron. 46 This glut of litigation is not a mere fluke, nor solely the result of a powerful trial lawyers’ lobby in Congress. The federal securities laws are intended to guarantee the flow of accurate information to investors, and therefore provide ample opportunities for private claimants to seek remedies through the US courts in civil actions. Allowing investors to sue under federal law lessens the regulatory burden on government agencies, as it allows private parties to seek recourse through the courts. Although remedies may also be available to investors under state securities laws or common law principles of fraud or negligence, private litigants are likely to be prohibited from asserting state law claims in large securities class action suits. Who may be liable Liability under the federal securities laws is far-reaching and broad and potentially affects the following: • Issuers in public offerings are generally subject to liability for materially misleading disclosure and omissions from registration statements, prospectuses, or other public statements. Under the broad anti-fraud provisions of Rule 10b-5 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the Exchange Act), issuers may also be liable to those who purchase or sell in the secondary market. • Underwriters and other professional advisers may be liable for materially misleading statements or omissions made in a registration statement or prospectus if they are viewed as the direct seller (such as in a firm commitment underwriting). Named experts (including accountants, engineers and appraisers) who prepare or certify a portion of the registration statement, or any report supporting the registration statement, are likewise subject to liability for the portions they prepare. Unlike issuers, underwriters and experts have a “due diligence” defence (see Establishing liabilities and remedies below). Finally, underwriters and other professional advisers (including lawyers and accountants) may be subject to liability under Rule 10b-5 for knowingly or recklessly making material omissions or misstatements. • Directors, officers (those required to sign the registration statement) and selling shareholders of the issuer may be liable for misleading disclosure. • “Control persons” are those who have the power, directly or indirectly, to direct the management or policies of others directly liable for the disclosure violation. Any control persons, including directors, officers and principal shareholders, may be directly liable for disclosure violations committed by an entity under their control. Types of statements Federal securities laws provide remedies for misleading disclosure for a broad range of misleading public statements, both written and oral: • Registration statements. Registration statements filed with the SEC (including the prospectus contained in the registration statement) can be a source of liability for untrue statements of material fact and materially misleading omissions (section 11, Securities Act of 1933 (the Securities Act)). • Prospectus liability. A seller may be liable for a prospectus (or oral communication) containing untrue statements of material fact or materially misleading omissions made in connection with a public offering, whether or not the offering is made pursuant to a registration statement filed with the SEC (section 12(a)(2), Securities Act). • Other public statements. Rule 10b5 provides one of the most significant remedies for disclosure violations, even extending to secondary market trading. Rule 10b-5 lawsuits may spring from material misstatements or omissions relied upon by investors, including press releases, financial reports and even analyst reports posted on an issuer’s website. Investors may also sue sellers under section 12(a)(1) of the Securities Act if securities were offered in violation of the registration requirements of that Act. A successful suit under section 12(a)(1) gives the investor a “put right” which refunds the purchase price of the securities. THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. CORPORATE: PROSPECTUS LIABILITY Sections 11 and 12(a)(2) and Rule 10b5 do not provide the only statutory remedies for improper disclosure in connection with securities offerings. For instance, section 17(a) of the Securities Act contains a broad anti-fraud provision similar to Rule 10b-5, which would apply to both public and private offerings as well as secondary trading. Section 17(a) does not, however, provide a private right of action, and suits can only be initiated by the SEC. This article therefore focuses only on those remedies provided by sections 11 and 12(a)(2) and Rule 10b-5. Establishing liability and remedies The causes of action provided to private litigants described above are not mutually exclusive. Rule 10b-5, which addresses cases where there have been misstatements or omissions in the sale of any security, public or otherwise, generally provides the broadest and most significant remedy for private litigants. 10b-5 claims are more difficult to establish than liability under section 11 and section 12(a)(2), which address misleading disclosure in registration statements and prospectuses in public offerings. In each case, a plaintiff bringing a claim must prove that the defendant made a “material” misstatement or omission, meaning that there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important in making an investment decision. The main differences between these causes of action are as follows: Actions under section 11. A plaintiff bringing a claim under section 11 is not required to show scienter (intent to defraud or manipulate) by the defendant, and defendants have the burden of proving an absence of causation. Defendants who are not issuers may escape liability by showing that they exercised “due diligence” in determining that the registration statement contained no material misstatements or omissions. If successful, plaintiffs are generally entitled to damages, although defendants may seek to reduce damages by showing that losses were attributable to factors other than the disclosure violations. A plaintiff bringing a section 11 claim will have to prove reliance on the misstatement or omission if the purchase was more than one year after the effective date of the registration statement and the issuer has made available to its security holders an earnings statement covering at least 12 months after the effective date of the registration statement. Actions under section 12(a)(2). As in section 11 claims, a plaintiff bringing a claim under section 12(a)(2) is not required to show scienter. Defendants have the burden of proving an absence of causation. Defendants, including issuer defendants, may escape liability by showing they exercised “reasonable care” in determining that the information released to the public contained no misleading material misstatements or omissions. If successful, plaintiffs are generally entitled to rescission, if the plaintiff still owns the securities, or damages if the plaintiff no longer holds them. Damages may be reduced if the defendant shows the losses were attributable to factors other than the disclosure violation. Rule 10b-5 claims. Plaintiffs bringing a claim under Rule 10b-5 generally bear a heavier burden and, in addition to establishing materiality, must demonstrate each of the following elements: • Reliance. The plaintiff must prove that it relied on the misstatement or omission. However, under the “fraud on the market theory”, US courts will presume reliance on a material misstatement or omission if the securities are traded on an established trading market. Under this theory, a material misstatement or omission will be deemed to have affected the market price of the stock, and courts will presume that the plaintiff traded in reliance on the integrity of the price set by the market (Basic v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988)). • Causation. A plaintiff must prove that reliance on the misstatement or omission caused the plaintiff’s loss. • Scienter. The plaintiff must prove that the defendant made the material misstatement or omission with some intent to defraud or manipulate. US courts have held that recklessness may constitute scienter (Citibank, N.A. v. K-H Corp., 968 F.2d 1489 (2d Cir. 1992)), but mere negligence will not (Aaron v. SEC, 446 U.S. 680, 690, 695 (1980)). If successful, private litigants in Rule 10b-5 claims may be awarded damages, or may seek to rescind the transaction and obtain a refund of the original purchase price. Other issues Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, claims alleging fraud, deceit, manipulation, or contrivance must be brought within two years after the discovery of the facts constituting the violation, and not more than five years after the date of the alleged violation. Wilful violation of the securities laws can lead to criminal penalties, including imprisonment of up to 20 years. Julian Copeman and Alex Bafi are partners in Herbert Smith’s London office, working in the UK and US practices respectively. Denis Chemla is a partner with Herbert Smith, Paris and Bettina Friedrich is a partner in the Frankfurt office of Herbert Smith’s alliance firm, Gleiss Lutz. THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 2003 ISSUE OF PLCGLOBAL COUNSEL MAGAZINE AND IS REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE PUBLISHER. PLEASE SEE WWW.PRACTICALLAW.COM/GLOBAL FOR MORE DETAILS. 47