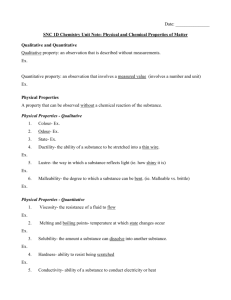

applications of qualitative and quantitative

advertisement