summer

2014

Harvesting Mango DNA

The Science Behind the King of Fruit

published by fairchild tropical botanic garden

The

Shop

at Fairchild

Mango salsa, $6.99

Member price, $6.29

home décor accessories | tropical gourmet foods

gardening supplies | unique tropical gifts | apparel

eco-friendly and fair trade products | books and much more

fairchild

Photo by Rey Longchamp/FTBG

tropical

botanic

garden

contents

features

The Call of the Wild:

The rebirth of the mango

plants

31 17 how

package seeds

departments

from the director 4

from the chief operating officer 5

schedule of events 7

get in on the conservation 9

tropical cuisine 11

explaining 12

vis-a-vis volunteers 15

what’s blooming 22

plant collections 29

edible gardening 45

what’s in store 51

gardening in south florida 59

plant societies 61

gifts and donors 62

garden views 65

from the archives 68

connect with fairchild 70

where others dare

38 Living

not: plants of the desert

from the director

A

spectacularly productive mango season has arrived in South Florida. Once again,

we are seeing and tasting the result of more than a century of mango research and

exploration. Our collection at The Fairchild Farm, now totaling more than 600

living accessions, was gathered from all corners of the mango world. During this

year’s International Mango Festival, you can enjoy the flavors, colors and incredible stories

from our collection.

This year, we launched a new program to study the genetics of our mango collection, adding

new dimension to our ongoing tropical fruit research. Visitors to the new Raymond Baddour

DNA Laboratory in the Paul and Swanee DiMare Science Village now have the opportunity

to see mango DNA research in action.

To learn about mango DNA, we gather leaf samples from our living mango accessions at The

Fairchild Farm and flash-freeze them in the lab with liquid nitrogen. In a cloud of steam, we

grind the super-cooled leaf samples into a fine, green powder. We use our lab equipment to

transform that powder into samples of pure DNA. As we stockpile hundreds of test tubes of

mango DNA in our freezer, we are building a tremendous resource for studying the mango’s

origin, diversity and potential breeding opportunities.

Our team of staff, students and volunteers is studying the mango DNA samples in our rapidly

expanding collection. This summer, a group of high school interns will help the project

grow, bringing new samples from The Farm to the laboratory for analysis.

In this issue, Noris Ledesma, Fairchild’s curator of tropical fruit, and Dr. Richard Campbell,

our director of horticulture, explain the incredible value of our collection for genetic

research and the future of mangos (“The Call of the Wild,” p. 31). Emily Warschefsky, a

Ph.D. Student at Florida International University, describes some of our goals in building this

research at Fairchild (“Message in a Bottleneck,” p. 34).

All of the world’s major crop plants, including rice, wheat, tomatoes and many others,

have been studied in detail through decades of DNA research. Results of that research have

helped rescue those crops from pests and diseases, and have brought valuable new varieties

to the market. We are only in the beginning stages of that kind of research on mangos, but

we see a bright future ahead. Any advances we make in mango genetics can positively

impact the livelihood of people throughout the tropics.

Along with the mango, there are hundreds of other kinds of tropical plants waiting to be

studied. Take a close look at our plants the next time you visit Fairchild, and you might catch

a glimpse of the small metal tags we use to identify and keep track of more than 12,000

plants. The majority of those plants have never been the subject of detailed genetic research.

Within our collection stand many new research opportunities just waiting to be tackled.

In the years ahead, you will see increasing numbers of researchers and students clipping leaf

samples from plants throughout the Garden and processing those samples in our labs. You can

look forward to new discoveries as we unlock the secrets held within the genes of tropical plants.

I hope you savor this mango season and dream of an even more flavorful future as science

moves forward at Fairchild.

Best regards,

Carl Lewis, Ph.D.

Director

from the chief operating officer

T

he temperature is warmer, the humidity higher and our umbrellas are in hand,

because, after all, afternoon showers are expected—all clear signs that summer

has arrived.

Fairchild is a tropical garden. Its 83 acres exhibit some of the world’s most exotic tropical

plants. Many of these plants thrive in the tropics, where temperatures average 80 degrees

year-round with consistent high humidity. South Florida is technically in the subtropics,

which means our average summertime temperature is in the upper 80s, but we experience

dry, cooler months in the winter. Summertime in South Florida is as close as we get to true

tropical weather. As a result, the tropical plants in the Garden are at their most spectacular

during these summer months. They respond to the higher temperatures and humid

conditions by seemingly bursting with verdant euphoria.

Summer also means mangos. Hearing “thump” when the first ripe mango of the season hits

the ground is the tropical world’s version of Groundhog Day: an unmistakable indication

that summer is here again. Fairchild celebrates the mango harvest with the annual

International Mango Festival (July 12–13), and this year’s event will once again bring mango

mania to South Florida. No other fruit arouses as much passion as the mango; the variety

of flavors and cultural resonances make it a truly global treasure. Our tropical fruit team

is working diligently to capture this global crop’s cultural, horticultural, agricultural and

scientific information. The Mango Festival is the culmination of the full spectrum of critically

important work related to the king of tropical fruit.

Summer also means family trips, vacations and weekend adventures. Be sure to make time to

visit Fairchild this summer. There are many activities designed to keep you cool during your

visit, like walking tours of the Rainforest and The Edible Garden, delicious smoothies of fresh

fruit from The Fairchild Farm, tram tours and, of course, the Wings of the Tropics exhibit and

adjacent Glasshouse Café, which is a perfect place to cool off and enjoy a great meal while

watching the dance of the butterflies.

I hope you enjoy the wonderful articles in this issue. Our staff spends a great deal of time

carefully crafting stories that illustrate both the botanical world at large and the Garden’s

important work. For instance, we present a great article about the oft-overlooked beauty and

utility of seeds, a fascinating look into consumption and conservation of edible orchids in

China, a beautiful travel and photo log of plants from the Mojave Desert, a delicious recipe

for mango ceviche that is perfect for all of those mangos you’re harvesting from your trees, a

step-by-step guide to growing the sacred lotus and so much more.

So this summer, come on over and enjoy mangos, the beauty of tropical plants in full splendor

and the endless possibilities of fun and learning that are offered only here at Fairchild.

Warmest regards,

Nannette M. Zapata

Chief Operating Officer and Editor in Chief

summer 2014

5

advertisement

contributors

Pond problems?

we are your answer!

Noris Ledesma is

the curator of tropical fruit

for Fairchild. She is a plant

collector and tropical fruit

specialist focused on mangos,

and has spent the last decade in

tropical Asia, Africa and North

and South America searching

for new fruit and lecturing on

their care and production. She is

currently working on her Ph.D.

in Mangifera species and their

contribution to the people

of Borneo.

We do it right

the first time!

305-251-POND(7663)

www.PondDoctors.net

Licensed/Insured

Richard J. Campbell,

Ph.D., is Fairchild’s director

of horticulture and senior

curator of tropical fruit. A South

Florida native, he trained in

the physiology of fruit crops

for his master’s and doctorate

degrees, and has dedicated

over 20 years at Fairchild to the

conservation of tropical fruit

genetic resources and horticultural

outreach. He aspires to train

the next generation of tropical

horticulturists in South Florida.

GEORGIA TASKER

was the garden writer for The

Miami Herald for more than 30

years, and now writes and blogs

for Fairchild. She has received

the Garden’s highest honor, the

Barbour Medal, and a lifetime

achievement award from the

Tropical Audubon Society. She

is also an avid photographer,

gardener and traveler. She

graduated cum laude from

Hanover College in Hanover,

Indiana.

Emily Warschefsky

is a Ph.D. student in the joint

graduate program at Fairchild

and Florida International

University. Under the

supervision of Dr. Eric von

Wettberg, and in collaboration

with Fairchild’s tropical fruit

program, she is researching the

evolution and domestication

of the mango. She received

her B.A. in biology from Reed

College (Portland, Oregon)

in 2009.

Delivery and Installation Available

Richard Lyons’ Nursery inc.

inc.

Rare & Unusual Tropical Trees & Plants

Flowering

Flowering •• Fruit

Fruit •• Native

Native •• Palm

Palm •• Bamboo

Bamboo •• Heliconia

Heliconia

Hummingbird

Hummingbird •• Bonsai

Bonsai &

& Butterfly

Butterfly

PROUD MEMBER OF

www.RichardLyonsNursery.com

www.RichardLyonsNursery.com

richard@RichardLyonsNursery.com

richard@RichardLyonsNursery.com

@lycheeman1

@lycheeman1 on

on Twitter

Twitter

Nursery:

Nursery: 20200

20200 S.W.

S.W. 134

134 Ave.,

Ave., Miami

Miami

Phone:

Phone: 305-251-6293

305-251-6293 •• fax:

fax: 305-324-1054

305-324-1054

Mail:

Mail: 1230

1230 N.W.

N.W. 7th

7th St

St •• Miami,

Miami, FL

FL 33125

33125

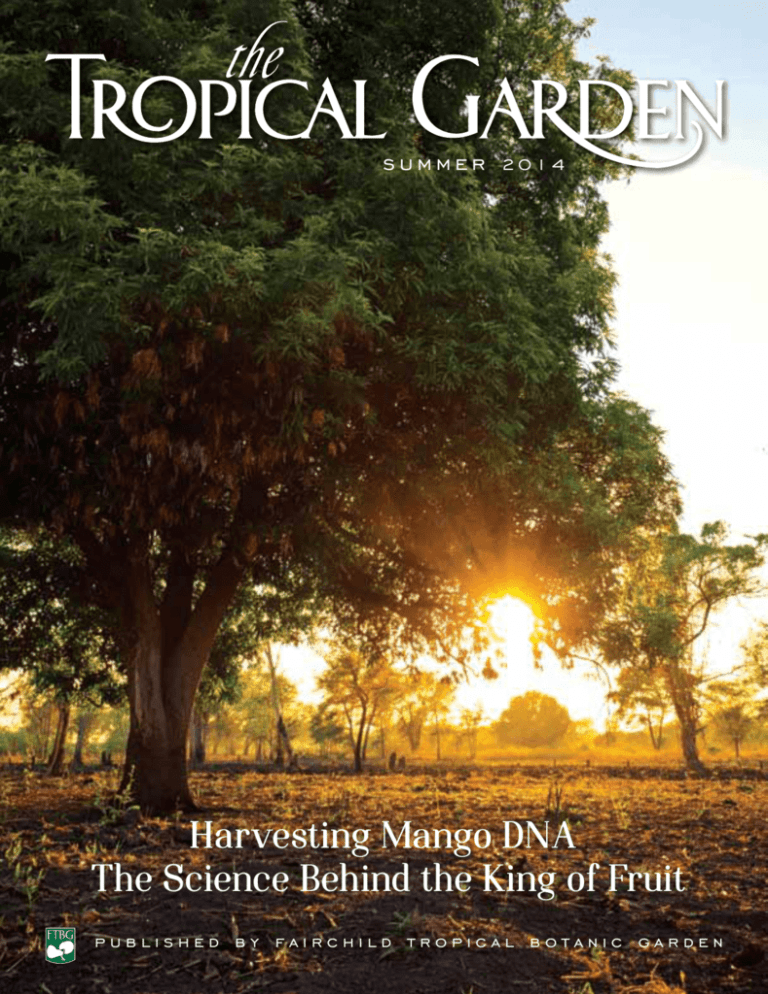

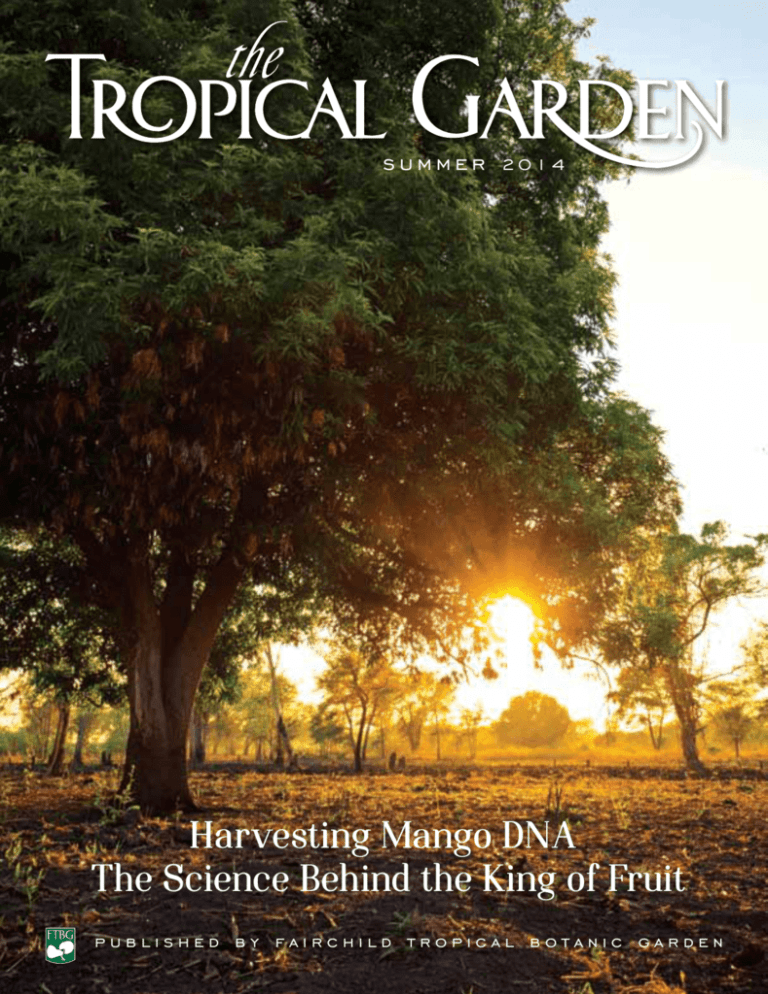

ON THE Cover

The sun sets on a

mango grove.

schedule of events

The official publication of

Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden

editorial staff

editor in chief

chief operating officer

Nannette M. Zapata

design

Lorena Alban

production manager

Gaby Orihuela

features writers

Georgia Tasker

Kenneth Setzer

staff contributors

Richard Campbell, Ph.D.

Mary Collins

Arlene Ferris

Erin Fitts

Mike Freedman

Marilyn Griffiths

Noris Ledesma

Hong Liu, Ph.D.

Brooke LeMaire

Emily Warschefsky

Sara Zajic

copy editors

Mary Collins

Rochelle Broder-Singer

Kenneth Setzer

advertising information

Leslie Bowe

305.667.1651, ext. 3338

previous editors

Marjory Stoneman Douglas 1945-50

Lucita Wait 1950-56

Nixon Smiley 1956-63

Lucita Wait 1963-77

Ann Prospero 1977-86

Karen Nagle 1986-91

Nicholas Cockshutt 1991-95

Susan Knorr 1995-2004

The Tropical Garden Volume 69,

Number 3. Summer 2014.

The Tropical Garden is published quarterly.

Subscription is included in membership dues.

© FTBG 2014, ISSN 2156-0501

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced without permission.

Accredited by the American Association of

Museums, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden

is supported by contributions from members

and friends, and in part by the State of Florida,

Department of State, Division of Cultural Affairs,

the Florida Council on Arts and Culture, the John

D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the

National Endowment for the Arts, the Institute of

Museum and Library Services, the Miami-Dade

County Tourist Development Council, the MiamiDade County Department of Cultural Affairs and the

Cultural Affairs Council, the Miami-Dade County

Mayor and Board of County Commissioners and

with the support of the City of Coral Gables.

July

weekend activities

Go to www.fairchildgarden.

org/weekends for

programming.

Plant ID Workshop

Friday, July 4

1:00 - 3:00 p.m.

Fairchild

International Mango

Festival Growers’

Summit

Friday, July 11

9:00 a.m. - 7:00 p.m.

The 22nd Annual

International Mango

Festival

Saturday and Sunday

July 12 and 13

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

Fairchild’s 15th

Annual Mango

Brunch

Sunday, July 13

11:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m.

August

Volunteer

Information Days

Tuesday, August 19

10:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m.

Saturday, August 23

10:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m.

September

Plant ID Workshop Friday, September 5

1:00 - 3:00 p.m.

Jackfruit Jubilee

Saturday, September 13

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

Volunteer

Information Days

Saturday, September 13

1:00 p.m. - 4:00 p.m.

Plant Show and

Sale Presented by the

International Aroid

Society

Friday, Saturday and Sunday

September 19, 20 and 21

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

Members’ Day

Plant Sale Saturday, October 4

9:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

November

Plant Show and

Sale Presented by the

South Florida Palm

Society

Saturday and Sunday

November 1 and 2

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

74th Annual Ramble,

a fall Garden Festival

Friday, Saturday and

Sunday

November 7, 8 and 9

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

Plant ID Workshop Friday, November 7

1:00 - 3:00 p.m.

October

weekend activities

Go to www.fairchildgarden.

org/weekends for

programming.

Bird Festival

AT Fairchild Thursday through Sunday

October 2, 3, 4 and 5

9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

Plant ID Workshop Friday, August 1

1:00 - 3:00 p.m.

Plant ID Workshop Friday, October 3

1:00 - 3:00 p.m.

This schedule of events is

subject to change. For up-to-theminute information, please call

305.667.1651 or visit

www.fairchildgarden.org/Events

Membership

at fairchiLd

Membership Categories

Your Benefits...

We have expanded and added membership

categories to better fit your needs:

• Free daily admission throughout the year

• Free admission to all daytime events and art exhibitions

• Free admission to the Wings of the Tropics Exhibit

• Free parking

• Free admission to all Members-only events, including

Members’ Lectures, Moonlight Tours, the Members’ Day

Plant Sale and select Members-only evening events

• Quick Admit at all admission points

• Subscription to the award-winning magazine

The Tropical Garden

• Discounts to all ticketed day or evening events

• Discounts at The Shop at Fairchild

• Discounts and priority registrations for

adult education classes and seminars

• Discounts to kids’ summer camps

• Discounts on a wide variety of products and services

from participating Branch Out Partners

• Free or discounted admission** to more than 500 other

gardens, arboreta and museums in the U.S. and abroad

(**certain restrictions may apply)

$90

Individual

Admits one adult

Dual

Admits two adults

$110

Family

$135

Grandparents

Admits two adults and grandchildren

of members (17 and under)

$125

Family and Friends

Admits four adults and children

of members (17 and under)

$170

Sustaining

$250

Signature

$500

Admits two adults and

children of members (17 and under)

Admits four adults and children of members

(17 and under). Receives six gift admission

passes ($150 value)

Admits four adults and children of members

(17 and under). Receives eight gift admission

passes ($200 value)

For more information, please call

the Membership Department at

305.667.1651, ext. 3362 or visit

www.fairchildgarden.org/Membership

fairchild tropical botanic garden

Photo by Gaby Orihuela/FTBG

fairchild

board of trustees

get in on the conservation

Bruce W. Greer

President

Louis J. Risi, Jr.

Senior Vice President

& Treasurer

Charles P. Sacher

Vice President

Suzanne Steinberg

Vice President

Jennifer Stearns Buttrick

Vice President

L. Jeanne Aragon

Vice President

& Assistant Secretary

Joyce J. Burns

Secretary

Leonard L. Abess

Alejandro J. Aguirre

Raymond F. Baddour, Sc.D.

Nancy Batchelor

Norman J. Benford

Faith F. Bishock

Bruce E. Clinton

Martha O. Clinton

Swanee DiMare

José R. Garrigó

Kenneth R. Graves

Willis D. Harding

Patricia M. Herbert

Robert M. Kramer, Esq.

James Kushlan, Ph.D.

R. Kirk Landon

Lin L. Lougheed, Ph.D.

Tania Masi

Bruce C. Matheson

Peter R. McQuillan

David Moore

Stephen D. Pearson, Esq.

Adam R. Rose

John K. Shubin, Esq.

Janá Sigars-Malina, Esq.

James G. Stewart, Jr., M.D.

Vincent A. Tria, Jr.

Angela W. Whitman

Ann Ziff

Clifford W. Mezey

T. Hunter Pryor, M.D.

Trustees Emeriti

Carl E. Lewis, Ph.D.

Director

Nannette M. Zapata, M.S./MBA

Chief Operating Officer

Fairchild Challenge Partners from 10 Institutions

Talk Collaboration

For more than 12 years, The Fairchild Challenge has been a role model for environmental

science education. Its simple structure of a school competition and the celebration of

students, teachers and schools make this program easily adaptable for environments from

the plains and canyons of Utah, to the urban settings of Pittsburgh and Miami, to rural

communities in the Amazon.

Over the years, national and international botanical gardens, arboreta, research institutions

and other community organizations have participated in workshops to learn how The

Fairchild Challenge can be replicated and integrated as an educational tool

at their own organizations.

In March, 10 partner institutions currently running The Fairchild Challenge program

met at Fairchild. They discussed the challenges of connecting students globally by

exchanging their projects and findings and looking for ways to create more opportunities

for collaboration. This summit was largely funded by the Institute of Museum and

Library Services, which recognizes The Fairchild Challenge as a benchmark for informal

education programs in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). The Institute’s

grant also funded program evaluation and the training of three new program partners.

Fairchild Ph.D. Student Earns Two

Prestigious Research Grants

Fairchild Ph.D. student Emily Warschefsky, supervised by Dr. Eric

von Wettberg of Florida International University and Fairchild, was

recently awarded two prestigious research grants. Warschefsky

was one of 20 graduate students from across the country selected

to receive the Botanical Society of America’s Graduate Student

Research Award, and one of 19 chosen to receive the American

Society of Plant Taxonomists Graduate Student Research Grant.

These awards will support Warschefsky’s dissertation research, which

aims to shed light on the genetic impacts of domestication in mangos

(Mangifera indica), investigate possible hybridization between the

mango and its wild relatives and elucidate the mango’s evolutionary

relationship to other wild Mangifera species. This issue of The

Tropical Garden features Warschefsky’s research work (page 34).

Fairchild Graduate Student Recognized

for his Work in Education

Jason Downing, a Fairchild Ph.D. candidate at Florida International

University under Dr. Hong Liu’s supervision and a Fairchild

Education Fellow, earned the UGS Provost Award for Graduate

Student Engagement. The award is given to outstanding FIU graduate

students who have demonstrated significant local, regional or global

engagement through a partnership that has led to demonstrable

community impacts. Downing earned this honor for his significant

work with The Fairchild Challenge.

Photo by Diana Peña/FTBG

Photo by David Hardy/FTBG

During his three-year tenure with The Fairchild Challenge, Downing

has mentored more than 500 public, private and charter school students

and teachers, mentored students through visits to their schools (using his

research on native orchids as a teaching vehicle), created and facilitated

teacher professional development workshops and coordinated events

and workshops for students at Fairchild. Most notably, for the past two

years Downing coordinated the Garden-wide Environmental Immersion

Day. His impact has been tremendous.

The Fairchild Challenge Students Create

Baynanza T-shirt Designs

Fairchild Volunteer Heading to Yale

to Study Science

At this year’s Baynanza Biscayne Bay Cleanup Day VIP Celebration,

the Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners and other

county officials recognized eight student participants in The Fairchild

Challenge (elementary school level) for their t-shirt designs.

Fairchild is fortunate to have many high school students who

take time out of their busy school schedules to volunteer at

the Garden. One such student is Omar Paez, (above) voted

“Most Intelligent” by his peers at Coral Reef Senior High.

Paez won an honorable mention in the Silver Knight Science

Award and was a Finalist for the Bill Gates Millennium

Scholarship. He volunteered in the Wings of the Tropics

butterfly exhibit, Metamorphosis Lab and Micropropagation

Lab, where Fairchild Director Dr. Carl Lewis allotted him

space for independent research.

Submitting a design for the Baynanza t-shirt was part of this year’s

Fairchild Challenge activities. Approximately 7,000 elementary

students from Fairchild Challenge schools participated in this

challenge, with 150 entries submitted for final judging. Eight of those

entries received highest awards, with Sofia Flores from Royal Green

Elementary earning first place. Flores’s design was printed on this

year’s Baynanza t-shirt, which was distributed to thousands of event

participants. Wearing their t-shirts proudly, fellow students, teachers,

family members and Fairchild Challenge staff attended the VIP event

to support the winning students and participate in this wonderful

community project.

10 THE TROPICAL Garden

“Highly motivated, goal oriented and always ready to learn,

Omar has been an invaluable member of the volunteer team

and an inspiration to many,” says Fairchild Horticulturist

David Hardy, who worked with him. Paez will soon begin

his freshman year at Yale University, where he will study

plant biotechnology and economics.

tropical cuisine

Mangos

Crisp and Green or

Ripe and Sweet

By Noris Ledesma

Mangos are intoxicatingly delicious. They should be eaten raw

and ripe on a street corner or over your kitchen sink. You have to

assume the right stance—legs back, chin forward, elbows out—to

avoid juice dripping down your arm. For a cook, they are the best

kind of ingredient because they require little help. Cooking with

mangos demands a simple preparation with only a few ingredients

so their true flavor stands out.

I

n Colombia, mangos are snacks

for any time of the day. They can

be breakfast, dessert or provide

natural juice for lunch or dinner.

Colombia is located in the tropics,

which allows for two seasons during the

year. The main growing season is during

our winter; the second, smaller season

comes during our summer. Mangos

in Colombia are available anywhere:

backyards, farmers markets and even

the corner street vendor’s cart.

Maduro o verde?

Mangos are sold on the streets of most

Colombian towns and cities and range

from sweet to salty, depending on the

preparation and type of mango. It is up

to you: sweet and ripe (maduro) or green

and tart (verde). Sold cubed and packed

in tall plastic bags, then sprinkled with

salt, mangos are the local snack. The

majority of mangos grown in Colombia

are ‘Keitt’ for the green market and

‘Azucar’ for those who love them sugary.

‘Azucar’ is widely considered the

national mango of Colombia, as its

flavor speaks to the tropical lowlands

and sweet cane sugar.

It is a polyembryonic cultivar that has

been savored by many generations of

children and the young at heart. The

average fruit weight is 220 grams, and

the color ranges from barium yellow

to azalea pink when exposed to the

sun. The flesh is saffron yellow with

coarse fiber throughout—but fret

not, for mango flesh is destined to be

softened and sucked out of the fruit.

‘Azucar’ can be found in street markets

throughout the Colombian lowlands

and can fetch high prices.

The tree is easy to grow, with consistent

production and a signature flavor not

to be missed. Trees will be available at

Fairchild’s Annual Mango Festival this

July 12-13, so don’t miss it.

It is always a plus when something

that tastes so good is actually good

for you. Mangos are blood builders

and a digestive aid. They stimulate

metabolism, which is always welcome

in my book. And, their high content

of iron, potassium, magnesium, beta

carotene and vitamins C, B1, B2, B3

and B6 makes them a valuable addition

to the fruit basket.

Mango Ceviche

Sweet mango, salty shrimp and tart lime

balance each other beautifully in this light

dish—great for a quick meal or as an elegant

appetizer!

2 cups fresh, ripe, but firm, mango—

chopped and peeled

1 cup green mango—chopped and peeled

1/2 cup fresh lime juice

2 tablespoons vinegar

1 tablespoon minced red onion

1 tablespoon minced red bell pepper

1 tablespoon chopped fresh cilantro

2 teaspoons minced garlic

1 1/2 teaspoons minced jalapeño

1/8 teaspoon salt

8 ounces raw shrimp, peeled, deveined and

cut into 1/4-inch pieces

Combine all of the ingredients except the shrimp

in a non-reactive bowl and stir well.

Add the shrimp and toss to coat with the

marinade, cover and refrigerate for two hours.

Arrange the ceviche mixture in a decorative

bowl or martini glass and serve chilled.

explaining

family

FUN

with nature

By Sara Zajic

For kids, summer is the perfect

time for relaxing with friends and

enjoying freedom from homework.

But when freedom turns to boredom,

it’s time for some new, creative ways

to inspire your kids. Beyond summer

reading, here are some great ways to

keep eager minds working, all while

having fun exploring and engaging

with nature, either at Fairchild or in

your own backyard.

Leftover Gardens

Food scraps can be used for compost, but there is also a lot

of everyday produce that you can re-grow. “Leftover gardens”

or “zombie gardens” are a hands-on way to introduce

sustainability, reusing materials and gardening. As an added

bonus, you get free produce. Popular and easy starters include

green onions, celery, basil and sweet potato. For more

ambitious gardeners, try re-growing pineapple or ginger. To regrow green onion: After using the greens, submerge the white

end with the roots in a glass of water, with a small portion

above the water. Place the glass in a sunny window and change

the water every few days. Harvest the greens as needed.

Solar Beads

If you need a motivator for your family to leave the couch

and go play outside, invest in solar beads, available online.

When you look at them indoors, the beads are clear, but when

exposed to UV light, they turn a variety of bright colors. Not

only are these stunning for unique, color-changing jewelry,

they are a starting point for important lessons about being

sun smart, especially in South Florida. Smear sunscreen on

some of the beads and leave others exposed. Which change

color faster? What does that tell us about the importance of

sunscreen? Next, compare beads placed in the shade versus

direct sunlight. Solar beads are also a fun way to jump-start

learning about solar energy.

Flower Pounding

For young artists, start a fashion trend using the

pigments of nature. This activity is best done outdoors

and lets your designers express themselves while getting

out a little extra energy. Pick several brightly colored

flowers and leaves from the garden and arrange them

in a pattern on top of a cotton shirt or bandana. Place

a piece of wax paper over the plant materials and

get to pounding! Once you have the desired effect,

move on to another piece until you’ve completed your

artwork. When you have the perfect pigmentation,

allow the piece to dry and heat set with a dry iron on

low temperature. The poundings should not be washed,

but they can be dry-cleaned. Now go and show your

pounded piece with pride!

Play with Your Food

Set up an experiment that gives young scientists an

inside look at what plants need as they grow some

yummy veggies. Using small pots or cups, plant 12

beans (green beans work particularly well). Label three

as the “control,” three as “low light,” three as “singing“

and three as “soda.” Make a hypothesis by guessing

which plants will grow the fastest. Place the three

control pots in a sunny spot and water every other day.

The three labeled “low-light” should receive the same

amount of water as the control plants, but place them in

a shady spot. For the three labeled “singing,” give them

the same light and water as the control plants, but talk

or sing to them every day. The soda group gets the same

sunlight as the control plants, but gets soda instead

of water. Let the race begin! Every few days, measure

the plants and record observations. Which plants are

growing the fastest? At the end of the summer, which

plant is the biggest? Why do you think this is?

Nature Journals

Create a journal to help young explorers look more

carefully at the nature in their own backyard. To make

your own journal, begin with a stack of scrap paper

and punch holes down the side. For a sturdy cover, cut

up a cereal box and turn it so that the plain cardboard

side faces out. Decorate the cover, and then use yarn or

ribbon to bind the journal. Have your young naturalists

sit outside and use their senses to explore and make

observations. Use a magnifying lens to see, up close,

the bugs and plants interacting. Listen to the sound of

the wind. How does it make you feel?

Have your young naturalists take their journals on field

trips, too. There are lots of exciting local nature centers

to visit, and some of them are even free. On August 25,

Everglades National Park will offer free admission for

the National Park Service’s birthday. Bring your journal

on a visit and compare and contrast what you see there

to the nature you see in your neighborhood.

All that, and More!

For amazing exposure to nature and plants from all

over the world, sign up for Fairchild’s Junior Naturalist

Summer Camp. Each weeklong session focuses on different

topics, ranging from Plant Explorers to Outdoor Skills

to Conservation. Campers become scientists, creative

thinkers, artists and conservationists through hands-on

activities, experiments and crafts. All the camps are

held in the one-of-a-kind Garden, and camp runs from

June 16 through July 25. Space is limited, so sign up today.

For fun with the whole family, check out Fairchild’s

new LEAF program. One weekend each month, there

will be free activities in The Learning Garden, perfect

for all ages.

Volunteering

at Fairchild

Become a Fairchild volunteer

and let a few hours of your

time blossom into a world of

new experiences!

Fairchild volunteers serve the Garden,

the community and the world through

their hands-on participation in Fairchild’s

programs and activities, while meeting

others who share their interest in plants and

gardens. Volunteer opportunities range from

gardening to guiding, hosting to helping

with the Wings of the Tropics exhibit.

To learn more about becoming a Fairchild

volunteer and how you can help the

Garden grow, come to one of our Volunteer

Information Days.

Tuesday, August 19

10:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m.

Saturday, August 23

10:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m.

Saturday, September 13

1:00 - 4:00 p.m.

For reservations and additional information

please call 305.667.1651 ext. 3360.

We look forward to seeing you!

fairchild tropical botanic garden

vis-a-vis volunteers

Taking the Time to Celebrate Volunteers

Fairchild’s Annual Volunteer

Appreciation Brunch

By Kenneth Setzer and Arlene Ferris. Photos by Fairchild Staff.

(L-R) Board of Trustees President Bruce Greer, Volunteer of the Year

Juanita Bayard and Garden Director Dr. Carl Lewis.

W

e often mention how

valuable our volunteers

are, and earlier this year,

we were able to show

them just how much we appreciate them.

The Volunteer Appreciation Brunch took

place on March 19 in the newly renovated

Garden House. Fairchild staff once again

turned the tables on our volunteers and

hosted, prepared and served more than 80

different dishes, including Jamaican jerk

chicken, Indian samosas, Vietnamese spring

rolls, mango bread, scones, dozens of salads

and two tables of desserts—there was truly

something to appeal to every appetite.

More than 300 volunteers came and

celebrated. They’re a fun group who

clearly enjoy each other’s friendship and

camaraderie—this was not your typical

reserved work brunch. They were all

eager to hear speeches from Fairchild

Director Dr. Carl Lewis, Board of Trustees

(L-R) Director of Volunteer Services Arlene Ferris

and Volunteer of the Year Kay Chouinard.

President Bruce Greer and Director of

Volunteer Services Arlene Ferris. All three

praised the dedication of our volunteers,

evident in their combined 80,000-plus

hours of service last year. You read that

correctly—that’s 80 thousand hours.

The gathering also celebrated volunteer

anniversaries with pin presentations

commemorating service from five to

40 years, and the Bertram Zuckerman

Volunteer of the Year Awards. This year’s

honorees are quite visible to all Garden

visitors. As two “faces of the Garden,”

Juanita Bayard and Kay Chouinard

can often be found guiding guests and

directing foot traffic at the Garden’s South

Entrance. Both women often summon

their extensive knowledge of Fairchild and

combine it with a smile and diplomacy

to work through any and all situations

they encounter.

Juanita Bayard has been volunteering

at the Garden since 2004, and has

contributed more than 5,000 hours. She

has assisted in various functions, including

admissions, education, membership and

volunteer services. “Volunteering here

has to be treated like a job,” Bayard said.

“Our responsibilities are vital in keeping

our Garden functioning as it needs to, but

at the same time it’s a lot of fun.”

Kay Chouinard has been volunteering

since 2008, contributing more than

3,000 hours to ensure a smooth flow of

operations not only at the busy South

Entrance, but also in admissions and

membership. “I feel it’s a privilege to

volunteer at Fairchild,” Chouinard said.

“I feel I get more out of being a volunteer

here than what Fairchild gets from me.”

summer 2014

15

In his speech, Greer compared Fairchild

to Renaissance-era Florence, Italy—a

place to celebrate nature, science and

art. This is true now more than ever with

the DiMare Science Village and Wings of

the Tropics exhibit in The Clinton Family

Conservatory both in full swing.

This leads us to a Fairchild first: The first

“Volunteer Team of the Year” award,

which was presented to the Wings of the

Tropics day captains. These 14 volunteers

ensure the exhibit’s hundreds of daily

visitors enjoy a fun and interactive

experience, keep the traffic flow

steady and answer questions about the

butterflies—all while ensuring all USDA

regulations are maintained. “This group

not only works extremely well as a team,

but they inaugurated the first year of

Wings of the Tropics,” Ferris said. “They

were there at the start.”

Lewis reminded everyone that, “the

Garden truly could not function without

its volunteers. There’s no way all of what

we do could be accomplished without

your selfless dedication and love

of Fairchild.”

Some of the 2014 Anniversary Pin recipients gathered in front of the Garden House

after the brunch. Volunteers wear their service pins proudly, and the longevity of

their service attests to their dedication to the Garden’s mission.

2014 Anniversary Pin Recipients

35 Years of Service

Barbara Katzen

30 Years of Service

Bruce Greer

Roger Hammer

25 Years of Service

Elizabeth McQuale

Wings of the Tropics Day Captains

(L-R): Ted Adelman, Ann McMullan, Jim Berlin,

Mimi Schwar, Jim Schmucker, Kathy Jones,

Glenn Huberman and Jeff Kaplan. Not shown:

Tom Abell, Frances Aronovitz, Anita Cody, Bill

Quesenberry, Mary Teas, Molly Whitman. At the

brunch Jeff Kaplan was quick to acknowledge

that the captains’ success depends on the great

volunteers who serve on their teams!

16 THE TROPICAL Garden

20 Years of Service

Lavinia Acton

Leonard Abess

Alejandro Aguirre

Elizabeth Beach

Joyce Burns

Phyllis Goldstein

Pat James

Yonna Levine

Jan Luykx

Tom Moore

Lane Park

Josef Pommer

John Soliday

Carmen Woodbury

15 Years of Service

Louise Bennett

Rosie Haning

Pat Herbert

Lynda LaRocca

Adele Mucha

Moyna Prince

Neice Schreiber

10 Years of Service

Maureen Adelman

Josefina Assa

Nancy Baldwin

Juanita Bayard

Tom Brown

Miguel Carson

Joe Cummings

Jim Cunningham

Jane Davidson

Polly Edwards

Ginny Guin

Barbara Lalevee

Lin Lougheed

Margaret Martin

Marigrace McCabe

Betty Oglesby

Paula Permetti

Susan Petersen

Janet Reed

Nancy Roberts

Mary Jo Robertson

Sandi Smith

Barbara Willig

Angela Whitman

Lorna Whyte

5 Years of Service

Julie Petrella Arch

Marlyn Asbel

Josie Batista

Marianne Bienstock

Ann Chitty

Carol Dieringer

Luisa Duran

Teresa Duran

Betts Faust

Mary-Anne Goseco

Magdalena Goudie

Twila Grandchamp

Gulcin Gumus

Susan Hangge

Susan Heckerling

Mary Rankin Jackson

Polly Kinslowe

Joel Kolker

Susan Pettapiece

Lucy Petrey

Wendy Robbins

Louise Ross

Candy Sacher

Sandy Sadlak

Adam Schachner

Jim Schmucker

Lola Schobel

Tighe Shomer

Susan Spatzer

Britt Steinhardt

John Struck

Margie Tabak

Deborah Van Coevering

Ted Weiss

Molly Whitman

How plants package

seeds

Clever, beautiful, ingenious:

plants’ glorious designs for their progeny

Text and photos by Georgia Tasker

Bulnesia arborea, a Caribbean tree

related to lignum vitae and introduced

by Dr. David Fairchild, has a five-sided

wind-dispersed pod called a samara,

each side containing a single seed. Never

have I seen a single pod fly, spin or

land, although they certainly must when

I am not watching because they are all

over the ground in spring. The papery

membrane that forms the pod or wings is

the dried inside of the ovary wall.

W

The Latin American Triplaris cumingiana,

or Long John, produces one-seeded dried

fruits known as achenes. The achenes

have three thin reddish calyces (the

collective term for plant sepals) that serve

as wings. Given the right breeze, they

detach from their twigs and spin to the

ground. The achenes are indehiscent,

which means they don’t open to disperse

their contents. They are the contents.

ind, animal, water or human dispersed, seeds and their packaging—be it fancy

or plain—have become my new obsession. The clever, beautiful, often ingenious and

sometimes practical packaging of seeds does not usually garner the adulation given

flowers. But many plants devise such marvelous ways of releasing their progeny that

they surely deserve World Heritage designation. With camera and macro

lens, I’ve been capturing samples of their glorious designs.

18 THE TROPICAL Garden

Amaryllis, or Hippeastrum cultivars,

produce three-parted capsules that split

back from the top to reveal black seeds

stacked like pancakes. They fall to

the ground.

Frangipani or Plumeria species have

double pods that resemble young horns

of Scottish Highland cattle. They stick

straight out to each side from each

other (as do the pods of the desert rose,

Adenium obesum). As the pods dry, they

split open, or dehisce. Inside are winged

seeds that make languid flight circles until

they softly touch earth. These pods are

called follicles, and they split only down

one side, freeing the seeds for flight.

Ptychosperma palms are fast-growing,

slender, palms that produce enormous

amounts of seeds—most of which will

sprout if given the opportunity. Yet, they

are able to take South Florida’s climate

and soils and are resistant to

lethal yellowing.

Mahogany trees, Swietenia mahogani,

produce large wooden capsules that

split from the base into five sections or

carpels that are reminiscent of the doors

of the old gull wing Mercedes sports cars.

Each compressed section contains tightly

and perfectly arranged winged seeds

(samaras, as Bulnesia arborea produces).

The wings are dry membranes that were

part of the fruit wall. When you find one

with the pedicel or stalk still attached, the

structure looks like a baby’s rattle.

Aristolochia vines form seedpods that

split along six seams. Inside some pods,

winged seeds are held in position by a

system of interlocking tissue that dries

to look like wire dish drainers without

any dishes. Many Aristolochia pods are

beautifully ornamental, and look like

inverted lacy parasols left over from 1930s

Busby Berkeley musical extravaganzas.

Goetzea elegans is a small tree found

only in Puerto Rico. In the tomato family,

its fruit is a strikingly pretty orange berry

containing several small, irregularly

shaped seeds in a juicy flesh. Little is

known about the endangered tree except

that only three populations, with

fewer than 50 trees, remain.

20 THE TROPICAL Garden

Once we knew it as Mimusops caffra,

but today it goes by Mimusops coriacea

(Manilkara bidentata), a cousin to wild

dilly and sapodilla. M. coriacea fruits

are round yellow berries, containing

one or two seeds, which are a beautiful

mahogany brown to black. Agoutis

(rainforest rodents from Central and South

America that resemble large guinea pigs)

or large birds disperse the seeds or they

remain not far from the tree.

Fruit of Clusia rosea is a spherical

capsule that ripens to split along several

seams into seven to nine sections.

Yellow seeds, when fully ripe, are

surrounded by red arils. From the

lower Florida Keys, Central and South

America as well as the West Indies, the

tree is a hemiepiphyte, meaning it starts

in the canopy of another tree, sending

long roots down to the soil.

Areca catechu is the betel nut chewed

by Bloody Mary in the musical “South

Pacific.” For people too young to

remember that wonderful musical, there

are more contemporary references to

chewing betel nuts in Papau New Guinea

and other islands, where the nut meat

combined with lime “makes a fellow

quite mellow,” and gives him red teeth.

A handsome palm, Areca catechu grows

throughout the tropical Pacific and can

be at home in South Florida, provided

the winters are not too harsh.

Ylang ylang, Cananga odorata, holds

axillary clusters of green fruits as well

as greenish yellow to yellow flowers at

the same time. Fruits contain six to 12

seeds. A pioneer species, the ylang ylang

is prized for the aromatic flowers and is

grown commercially for perfume.

Birds, bats and monkeys in

Indo-Malaysia eat the seeds.

What’s

Blooming

this summer

By Marilyn Griffiths

Photos by Susan Ford-Collins and Marilyn Griffiths

It has been eight years since the Lisa D. Anness South Florida Butterfly

Garden was inaugurated at Fairchild. It was a wonder to watch zebra longwings, julias,

hairstreaks and sulphurs flocking to find their favorite nectar and host plants immediately

following the exhibit installation. Over the years, the South Florida Butterfly Garden

has changed as plants have grown or as we have learned of new plants that attract other

butterflies. But the basic nature of this enchanted space has not changed: It is still

a magical haven for our delicate, brightly colored flying gems.

The list below is a small representation of the

plants found in the South Florida Butterfly Garden.

They are but a few of what you’ll find blooming

during the summer.

Callicarpa americana is native

from Florida to Texas and the

West Indies. Its delicate pink

flowers provide nectar for

many species of butterflies.

Birds are attracted to the

brilliant purple fruit, making

this shrub very popular with wildlife.

Lantana involucrata is native

through a wide range, from

peninsular Florida through

Central America, the West

Indies and South America, all

the way to the Galapagos. It’s a

shrub with fragrant, gray-green

leaves and white or pink flowers with a yellow center.

The fragrance of the flowers draws many different

types of butterflies, from tiny skippers to swallowtails.

When crushed, the leaves emit an unusual fragrance.

From my experience, this fragrance varies between

plants—from a soapy smell to the aroma of sage.

A very familiar plant in the

landscape, Pentas lanceolata,

is actually native from

Ethiopia to Mozambique,

the Comoros Islands and the

Arabian Peninsula. It has

been hybridized many times

to produce various shades of red, pink and white

flowers. Our native butterflies love the nectar

despite its foreign origins.

Monarch on Asclepias

curassavica

The red-flowered tropical

sage, Salvia coccinea, not

only draws butterflies to its

nectar—it also has the perfect

shape and color to attract

hummingbirds. This native of

the southeastern United States

and tropical Americas provides a vivid splash of

scarlet amid the foliage.

Senna polyphylla, desert

senna, is native to Puerto

Rico, Hispaniola and the

Virgin Islands. Sulphur

butterflies use the plant as

a host for their larvae. Pale

yellow flowers camouflage

the butterflies and, when disturbed, it appears that

the flowers are lifting off into the air.

Calotropis gigantea (shown)

and Asclepias curassavica are

two plants in our Butterfly

Garden that attract monarchs

to their nectar and provide

the proper diet of leaf material

for their larvae. Don’t be

surprised to see leafless stems—it means the

monarch larvae have had a delicious meal! Neither

plant is native to Florida, but again, this doesn’t

matter to the monarchs.

There is a nationwide effort to provide nectar and

host plants for the monarch butterfly, which is

threatened by disease and habitat disruption.

Visitors to Fairchild can obtain a plot map of

the Garden, which includes a list of currently

flowering plants, at the Shehan Visitor Center, the

South Entrance Gate and the information kiosks

located throughout the Garden. Volunteers at

the Visitor Center information desk also have a

complete list of Fairchild’s plants.

Our website is an invaluable resource for Garden

information, including lists of plants with their

locations—organized by both common and

scientific names—a downloadable map of the

Garden with plot numbers and a resource of

blooming plants for each month.

Visit www.fairchildgarden.org to find all

this, plus information about gardening,

horticulture, conservation and plant

science, as well as information about all

of Fairchild’s exhibits.

summer 2014

23

advertisement

Carrie C. Foote

realtor

“Let a native help

you establish roots”

cfoote@lowellinternationalrealty.com

786.837.3987 | 305.520.5420

www.somirealestate.com

sold

sold

837 OBISPO AVENUE

6 6 4 0 S W 1 2 9 TH T E R R A C E

CORAL GABLES: HISTORIC HOME

PINECREST: LUSH TREE LINED HOME

12900 SW 89 Court, Miami, FL 33176 | 305.233.1322 | originalimpressions.com

Experience a luxurious tropical garden with

a large selection of proven and exotic

plants for South Florida

Orchids, begonias, water lilies, vines,

flowering trees and shrubs. rare plants,

butterfly plants, supplies and more

Landscape design | Waterfalls

Pond installation | Water features

Palm Hammock Orchid Estate, Inc.

Est. 1973

Visit our website, then visit our garden

9995 SW 66 St. Miami, FL 33173 305-274-9813

www.palmhammock.com

AT FAIRCHILD

IS ANYTHING BUT SLOW!

By Kenneth Setzer

There’s lots more to do during the

summer. Here are just a few activities

you can find at Fairchild.

The International Mango Festival is one of our biggest celebrations. On

July 12 and 13, join us for an exploration of the king of tropical fruits. You

can learn how to cook with mangos and how to grow them, plus take part

in mango tasting (did you know there are more than 600 varieties?). Trees

carefully selected by our curators will also be available for purchase.

Most of our events have activities for kids, but if your kids really want

to dig in deep, Fairchild Summer Camp is the way to go! We offer two

options: KoolScience and Junior Naturalist. Both options will introduce

your child to the wonders of nature and the world of science. It’s the

perfect way to make learning fun.

On weekends, stroll through the Garden and discover new spots through

a self-discovery walk, or explore butterflies and their host plants on our

guided South Florida Butterfly Gardening tour, which starts at the Shehan

Visitor Center every Saturday and Sunday.

Volunteers will be waiting for you at the Rainforest, where every Saturday

and Sunday from 11:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. you can hear interesting stories

about the plants and animals that inhabit this diverse ecosystem.

On selected weekends, learn how to create your own edible garden at home

and enjoy interpretative talks on the unique plants housed in the Tropical

Plant Conservatory and Rare Plant House. For walking tour details, please

remember to check the website at www.fairchildgarden.org/walkingtours

and inquire at the Visitor Center’s information desk upon arrival.

Every weekend, fresh smoothies from fruit harvested at The Fairchild Farm

will be available for purchase in The Edible Garden. On select weekends,

expert volunteers will offer tours of The Edible Garden.

Stroll through the Wings of the Tropics exhibit to be amazed and captivated

by its incredible landscape, flowering plants and hummingbirds, plus the

stars of the show: thousands of tropical butterflies.

summer 2014

25

Anolis sagrei

Anolis carolinensis

How You Can

garden

anoles

Encourage and Protect Your

By Mike Freedman

A

s Garden residents, it’s hard to beat our daytime

lizards, the anoles. They eat insects—great for

us—and are highly entertaining to watch, as they

display, chase and gobble unwary cockroaches. In South

Florida, you’re likely to see four species, each with a

particular preferred habitat, special appearance

and behavior:

Anolis carolinensis

Our only native anole. Sometimes called “green anole,”

“Carolina anole” or “chameleon” (it’s definitely not a

true chameleon), its color ranges from various shades of

brown to bright green and it has a pink dewlap (throat

pouch). Look for this anole on something elevated—a

wall, a fence, a tree trunk—and, rarely, on the ground.

26 THE TROPICAL Garden

My favorite anole. This is the “Cuban brown anole” or

“brown anole.” It’s our liveliest and most-often-seen

anole, and as its common name implies, an import

from our island neighbor. Its colors range from tan to

dark brown, usually with a diamond pattern, plus a

dewlap that is red with white or black spots. You will

see this anole scooting across the sidewalk or sitting

on your front steps. Occasionally, they’ll climb onto

something, maybe to see and hear you better.

Anolis equestris

Our largest anole (12 inches or longer, including tail).

Sometimes called “knight anole,” “Cuban knight anole”

or “Cuban anole,” it’s another Cuban import. This one

can range in color from dark brown to bright green,

with a yellow shoulder stripe and a pink dewlap.

Except when falling out of them, they spend all their

time in trees.

Anolis distichus

Our fastest anole. A. distichus has been listed as

emigrating from various nearby islands. The common

name for this anole is “bark anole,” probably because

it blends so well with tree bark. Its range of colors goes

from light gray to almost black, sometimes with darker

chevrons, accented by a yellow-green dewlap. You’ll

almost never find bark anoles on the ground. Look for

them standing out from tree trunks. They move in bursts

of speed; they can run, but they don’t know how to walk.

Help Anoles Help You

I shouldn’t have to do much selling to convince

homeowners that anoles are just about the greatest

things you can have in your garden. Don’t worry about

feeding them—they’ll dine on your unwanted insects,

but when it’s been dry for a long period, you might

consider spraying some water on your bushes. Thirsty

anoles will run over to lick up water drops on leaves.

Try to discourage predators, such as cats and terriers.

Consider establishing a safe area that will be difficult

for pet predators to access. Here are a few more small

things that you can do to protect these helpful creatures:

Mowing

Anoles like to hunt a few feet out from their “safe

zones” of bushes and plant beds. Often, a mower

can cut them off (literally) from that safe zone. If, just

before mowing, you can walk the edges of plant beds,

a couple of feet out, you will scare the anoles back

into their bushy safe zones. In summer, tiny hatchlings

might need a helping hand to reach safety.

Fun with Anoles

Anolis distichus.

Photo by Kenneth Setzer/FTBG

Indoors

Anoles cannot survive in your house. Your dog may

be able to drink from the big porcelain water bowl,

but it is inaccessible to anoles. Be humane and show

them the way out. Should you see lizards on your

wall at night, they are probably geckoes. Geckoes are

generally able to survive fine inside houses; a bonus:

They eat insects!

Walking and cycling

You’ve probably been surprised and irritated by

lizards that dart out in front of your foot or bike tire.

This is the same situation that we saw with mowing.

Anoles go out onto the sidewalks and may even cross

the sidewalk to look for insects and socialize. When

cycling, I try to go slowly in zones with heavy anole

traffic. If you’re walking, try slowing down when

you pass bushes and keep to the side without bushes

when possible. That should give anoles time to get

back to their safe zones.

Eggs

Anoles lay eggs in spring and summer. The eggs are,

well, egg-shaped and generally about a quarter inch

across (A. equestris eggs are about an inch across).

They’re white and rubbery, like small oblong rubber

balls. Eggs are laid in the upper half inch of soil and

leaf matter. You might encounter them in summer,

when weeding or even when working with potted

plants. The best thing to do is to rebury them to

about the same depth as they were buried by the

female anole.

Anoles are about the most entertaining animals you

can have in your garden. They play and catch insects.

They don’t have any of those hairy or pointy parts that

insects have. They have good eyes and seem to hear

well. Just sitting and staying still near bushes can be

fun. If you’re very still, anoles might eventually see

you as some sort of oddly shaped tree and decide to

climb on your shoe. This can be fun for kids with lots

of patience. Less patience is required to view sleeping

anoles. An hour after dark or before dawn, go out with

a flashlight and look at some of the lower horizontal

leaves on shrubs. You’re likely to see anoles stretched

out, immobile, with their eyes closed.

It’s also possible to arrange a nice meal for anoles,

with either of their two favorite foods: cockroaches

or maggots. The procedure is the same for either.

Take a piece of cardboard or a garbage can lid with

roaches or maggots on it and toss it onto an open

space, like a patio. As the insects emerge, watch the

anoles come running over for the banquet.

The last fun activity is to have an anole sit on your

hand. Kids should love this one, but care is needed.

This is best done in summer, when there are lots

of baby anoles in the grass. You can put one hand

on the ground near the anole and encourage it to

go toward that hand by moving your other hand in

the grass. If done right, you’ll guide the lizard right

onto your hand. It’s best not to try to grab lizards, in

general. Their tails come off easily and that can really

traumatize kids, but you could take this opportunity

to explain that it’s normal, the tail grows back and

coming off allows the lizard to escape predators.

Anoles—they’re a bit of wild nature that has taken up

residence in our gardens to engage in insect cleanup

and provide pleasure for us in the process.

Anolis equestris

Anolis sagrei

Photo by Kenneth Setzer/FTBG

NANCYBATCHELOR

305 903 2850

WWW.NANCYBATCHELOR.COM

Fairchild magazine_Feb.14.indd 1

1/15/14 5:26 PM

plant collections

Fairchild’s world-renowned

Cycad Collection

By Marilyn Griffiths

Fairchild’s cycad collection is one of the world’s most

extensive, on par with our palm collection. Palms and

cycads, though sometimes similar in appearance, are very

different and not closely related plants.

M

cycad genera Ceratozamia, Chigua, Dioon,

Microcycas and Zamia. Encephalartos and

Stangeria are found in Africa. One species

of Cycas is found in a small area of Kenya,

but it is believed that it was brought there

sometime in the last 1,000 years. All

other Cycas species are from Australia,

Asia and Malesia. At Fairchild we have

representatives of all genera except Chigua.

any of our cycads were

donated to the Garden in its

early years by our founder,

Col. Robert Montgomery.

Since then, numerous species from

around the world have been added to the

collection, making it an invaluable resource

for scientists studying this fascinating order

of rare plants and for visitors appreciating

their unusual and primitive beauty.

Cycads are gymnosperms, along with

conifers and gingko, meaning they are not

among the flowering plants (angiosperms).

They are dioecious (plants are either male

or female) and reproduce by developing

a cone containing seeds. Some cones

can become very large—a foot or more

in length—and many are bright red,

orange or yellow. Sometimes called “fossil

plants,” cycads were abundant throughout

the world more than 200 million years

ago. Now reduced in range and number,

cycads comprise 250 species, compared

to flowering plants’ 300,000 species.

Used as ornamentals, cycads can be a

beautiful part of the landscape. But taking

plants from the wild for this purpose has

threatened the existence of many species.

For instance, only male plants of the

African species Encephalartos woodii

remain in the wild. The Florida native

cycad, Zamia integrifolia—the coontie—

was almost collected out of existence

when pioneer settlers gathered plants

Dioon edule

from the wild for their starch-producing

businesses. Fortunately, conservation

efforts have prevented the loss of this

incredible plant, the only known host

for our native atala butterfly. Today, all

cycads are covered by the Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species

of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

All cycads have toxins in every part of

the plant. Animals grazing on them suffer

severe symptoms and possible death.

Proper processing of the plant material,

such as boiling the coontie root for starch,

is essential if it’s going to be consumed.

Cycads can be found globally in tropical

and subtropical climates with moderate to

high rainfall. The Americas are home to the

The oldest plant at Fairchild is a cycad:

Dioon edule. One Dioon edule (found in

the Cycad Circle) made a circuitous path

from Edinburgh, Scotland, to Milwaukee,

Wisconsin, to Naples, Florida, and finally

was donated to Fairchild in 1940. One leg

of its journey is unknown: How did it get

from its native Mexico to Scotland in the

first place? When purchased in Scotland

in 1867 it was reputed to be at least 100

years old. It still thrives in Plot 124 of

Cycad Circle.

A few of the more tropical Zamia species

must be protected from South Florida’s

mildly chilly winter temperatures. They can

be found in the Tropical Plant Conservatory,

where they flourish and reproduce.

Look for our other magnificent cycads in

the Montgomery Palmetum, Cycad Circle

(Plot 124) and the Cycad Vista. These

ancient, sturdy plants can remind us of

how recently we humans have occupied

the planet and the need to preserve our

natural history.

advertisement

xotic Orchids in a Lush Tropical Setting

Visit R.F. Orchids,

South Florida’s oldest and

most prestigious orchid

firm, for the finest selection

of quality orchids in town.

Exquisite gifts, stunning

floral arrangements and

more await you in our

tropical paradise.

28100 SW 182 Ave. | Homestead FL 33030

T: 305-245-4570 | F: 305-247-6568

www.rforchids.com

For Sale by owner

20914 Morada Court, Boca Raton

4-2½, 2400 sqft, large pool, gated community (no guard),

end of cul-de-sac, one-half acre.

Fantastic landscaping–mature cypresses, albizia caribe,

strangler figs, oak, elm, gumbo limbo, palms, cycads,

fish ponds, and more.

Tasteful, immaculate interior with built-ins.

$745k

By appointment only (ask for Bill or Sarah)

(561) 483-7788 or whhsmsh@gmail.com

The Call

of the Wild

The rebirth of the mango

By Noris Ledesma and Richard J. Campbell, Ph.D.

PREVIOUS PAGE

Wild mangos are generally restricted

to the wet tropical lowlands below

450 m elevation, frequently in

inundated areas, along riverbanks.

It is common to find it cultivated in

villages in Borneo.

LEFT

Collection and domestication has

been a long and complex process

but has really only just begun. At

the Fairchild Farm, wild mangos are

isolated in a cage to create a new

generation of mangos for the future.

Photo by Noris Ledesma/FTBG

We, as residents of South Florida, lay claim to the

mango. Regardless of its Asian origin and pan—

tropical distribution, the mango belongs to us.

E

ach year, we care for our trees and await the

harvest. Each year we face challenges, with

nature seemingly pitted against the crop, but

summer eventually arrives and so, too, does

the mango. Yes, the mango comes through

for us. We shaped the fruit into our Western

ways, poked and prodded until it was exactly what

we wanted and was something we could exploit for

income. It is ours.

Dr. David Fairchild was the mastermind behind the

transformation of the mango from a traditional Asian

fruit to a marvel of modern fruit growing. More than

a century ago, he had an innovative vision for the

mango that has paved the way for the introduction

of hundreds of cultivated varieties from around the

globe into South Florida. He and a handful of mango

pioneers assured the mango’s propagation and care

and facilitated its cross breeding and the selection of

superior progeny. This long road of vision and science

32 THE TROPICAL Garden

has led us to the point we are at today. All around

us, we have mangos big and small, red and yellow,

sweet and sour and truly amazing. All of this mango

diversity and delicious economic potential came from

a thorough shuffling of the genetic deck, a keen eye

and an undying tenacity.

We are now more than a century removed from the

innovative work of David Fairchild, and the mango

is in need of another makeover. A host of old and

new pests and diseases nip at the mango’s heels. The

climate, ever-changing, challenges the mango each

year. We are nervous, even desperate to intervene,

but surely we should not submit to the chem-agro

mindset of mango growing to be successful. What

of our green future and that of our children? No, we

must be strong in our convictions and in our science.

We must take a step back in the genetic sense to

move forward into the next millennium.

Unlocking the Potential

of the Wild Mango

So onward we go into the forests of Borneo and

Southeast Asia to learn of, and cultivate, the wild

mangos that grow there. These 70 or so edible species

offer adaptability to the most inhospitable of mango

climates. Each is genetically distinct from the cultivated

mango that we all know. Each has its own name

among the tribal people who rely upon them. They

range from huge to tiny in fruit size and burst forth in a

dizzying array of colors, shapes and flavors. They grow

in swamps and at higher altitudes throughout Southeast

Asia and are a staple for man and beast alike. Yet,

these wild relatives of the cultivated mango remain

largely a mystery, with little understanding of their

cultivation, their propagation or even their genetic

identity. Confusion surrounds the wild mangos around

the globe with many more questions than answers,

but the potential is there; it lays dormant within them.

Now is the time to unlock this potential.

At Fairchild, we grow more than 40 accessions of

wild mango in the living collections, constituting 25

species or more. Prior to these introductions, wild

mangos were represented in South Florida by three

or four recognized species. This handful of species

was made up of multiple duplicate trees of a single

introduction made many years ago by Dr. Fairchild.

Other introductions of wild mangos had been

attempted in the past, but they were unsuccessful,

leading mango pundits—including David Fairchild—

to the conclusion that the vast majority of wild

mangos would not adapt to South Florida. We have

spent the last 25 years attempting to disprove this

commonly held belief. We have had some success

and much failure. Forty trees may not seem like much

of a track record for 25 years of collecting, but there

is no script available to go by. Identification, location,

collection, propagation and care in the field have

been done without a template, and yet here these trees

grow, bloom and fruit, swaying in the ocean breezes.

So, how does this winding story relate to our

backyards and commercial orchards in South Florida

and the Americas? As we pen this article, we have

new crossbreeds hanging from our caged trees at

Fairchild. These crosses will be among the first

between wild mangos and some of our high-yielding,

most-modern mango cultivars. The seeds within these

fruit hold the future—a future without concern about

untimely rains, without the application of costly

fungicides and with novel new fruit.

We will plant these seeds and nurture the saplings

until they bear their sweet fruit. We will select new

superior specimens that have disease tolerance,

high production and the ability to adapt to our everchanging climate. The road is a long one, by no

means easy or guaranteed, but each journey begins

with a single step. Our journey started back in 1889

with David Fairchild and there is much road left to

travel. His legacy depends on us, and so, too, the very

future of the mango.

Binjae (Mangifera caesia): The

white flesh mango. In Malaysia,

this is one of the most common

and valuable mango species. It

is used to make the traditional

dishes ‘sambal’ and ‘jeruk’ and

eaten with fish.

Photo by Noris Ledesma/FTBG

summer 2014

33

Message

ck

lene

in a Bo’stt

Journey Revealed

The Mango

through History and Genetics

By Emily Warschefsky

Its introduction into the Americas

and its spread around the world may

have decreased the mango’s genetic

diversity. But now, Fairchild scientists

are helping conserve mangos’ genetic

diversity around the world.

M

angos are grown on every continent

except Antarctica, and everywhere

they are grown, they are wildly

popular—so much so that many

people in the Americas are surprised to learn that

the mango is native to South Asia, and was only

introduced to the New World during the last 300

years. How did the “King of Fruits” spread from its

homeland in South Asia to countries as far away as

Colombia? Historical records can help us trace the

migration of the mango.

The mango is considered native to the foothills of the

Himalayas, in the region of modern-day northeast

India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar. Based on

cultural artifacts, it is estimated that the mango has

been cultivated in that region of the world for more

than 4,000 years. The mango is significant to many

religions of South Asia, particularly Hinduism and

Buddhism, and it is said that Buddha himself was

given a grove of mango trees under which to rest and

meditate. Buddhist monks likely began to introduce

the mango into Southeast Asia during the third

century B.C.

More than a millennium passed before the mango

began its journey westward out of India, making its

way to east Africa through Persian trade routes during

the 10th century. During the 1500s, Portuguese

traders spread the mango to their colonies throughout

Africa. The mango reached the shores of the

Americas only in the early 1700s, brought to Brazil

by the Portuguese. From there, it spread into the

Caribbean during the middle of the century.

The Spanish first introduced the mango to Acapulco,

Mexico during the late 1700s, bringing it across the

Pacific Ocean from Manila, in what was then the

Spanish East Indies (and is now the Philippines).

Shortly thereafter, Caribbean mangos were

Mangos found their way to the sandy beaches

of the Caribbean during the 1700s.

Photo by Emily Warschefsky/FTBG

introduced to eastern Mexico. The first records of

mangos in Florida do not appear until 1833, though

it is likely that the ‘Turpentine’ mango—named

after its characteristic acrid flavor—had already

been introduced by that time. In 1889, Dr. David

Fairchild, working for the U.S. Department of

Agriculture, brought the first grafted Indian varieties

back to South Florida. Although the mango took

its time getting here, it was not long until our local

mango industry began to make its mark, producing

cultivars that, even today, are some of the most

popular in the world.

While historical documents allow us to piece

together a rough timeline of the mango’s migration

around the world, the impact that this series of

introductions had on the mango’s genetic diversity is

a fundamental question that remains unanswered.

The extent to which a crop has lost genetic diversity

over time is of interest to agriculturists and scientists

alike. During the process of domestication, crops

lose genetic diversity, as a few individuals with

summer 2014

35

Crop genetic diversity has been lost

Wild species

High diversity

Traditional crops

Moderate diversity

Domestication

Bottleneck

Modern crops

Low diversity

Migration and

Breeding Bottleneck

Human selection for certain traits

during domestication results in a

loss of genetic diversity, called a

genetic bottleneck. Subsequent

migration and breeding for “elite”

varieties further reduces crop

species’ diversity. Such dramatic