NGO™s in the Biological Weapons Convention: Agents of

advertisement

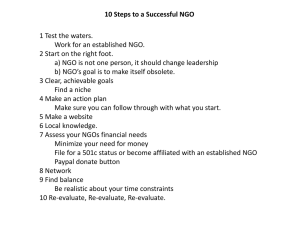

NGO’s in the Biological Weapons Convention Agents of contestation? Niels van Willigen Institute of Political Science, Leiden University (willigen@fsw.leidenuniv.nl) Koos van der Bruggen Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (koos.van.der.bruggen@knaw.nl) Paper presented at the: 7th ECPR General Conference Bordeaux 4-7 September 2013 EARLY DRAFT: PLEASE DO NOT QUOTE Introduction Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO’s) are strongly involved in global governance. In the academic literature NGO’s are depicted as agents with an increasing influence on world politics. In some cases of multilateral cooperation, for example the Anti-Personnel Landmine Convention, the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM), NGO’s significantly influenced the outcomes of the negotiations (Short 1999; Williams, Goose & Wareham 2008; Doherty 2009). In these particular two cases NGO’s formed an important part of a larger transnational advocacy network (Keck and Sikkink 1998) which successfully fought for the abolishment of two entire categories of weapons. At other occasions, NGO’s made their voices heard against the downsides of globalization and protested at meetings of the WTO and the G8. Hence, NGO’s are often seen as agents which resist, contest, and/or transform the status quo in world politics (Steffek 2013: 8). There is however another, and arguably more realistic, qualification of the role of NGO’s in world politics. NGO’s are more often partners of international organizations and states than agents of contestation. A case in point is the way NGO’s function in the United Nations (UN) where they cooperate with the member states and other international organizations to such an extent that they have become ‘integrated and institutionalized’ within the UN system (Dany 2013: 4). Partnership also occurs in the above mentioned transnational advocacy networks which are coalitions of amongst others NGO’s, (parts of) International Governmental Organizations (IGO’s) and (parts of) the executive and legislative branches of governments (Keck and 1 Sikkink 1999). As institutionalized actors, NGO’s may still change and transform global governance, but not necessarily as an agent of contestation. Instead of challengers to the state, they can be considered as partners which enhance the abilities of the state in global governance (Raustiala 1997: 720). In this paper we analyze the role of NGO’s as partners of the States Parties of the Biological and Toxins Weapons Convention (BTWC). The BTWC - officially the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction - was signed in 1972. Since then, the treaty has evolved into the most important multilateral institution addressing the problem of biological weapons. In many ways the BTWC is a classic treaty in which the States Parties are the most important actors. Although the growing role of NGO’s in world politics is generally acknowledged, reservations are often made with respect to the role of NGO’s in international security (Knopf 2012: 169). The aim of this paper is to understand the role of NGO’s in the BTWC. Based on resource exchange theory, we offer an analysis of the role of NGO’s in this multilateral treaty regime. Resource exchange theory holds that NGO’s gain access to IGO’s in return for their expertise. Steffek (2013) recently presented a theoretical framework which, based on resource exchange theory, aims to offer ‘a more systemic approach to the analysis of IGO-NGO relations’. We argue that his framework can also be applied to analyse state-NGO relations within a treaty regime which lacks a treaty organization as is the case in the BTWC. 2 We start the paper with an elaboration on resource exchange theory. Special focus is given to Steffek’s framework. Secondly, we analyse the role of NGO’s in the BTWC. What kind of NGO’s are involved in the treaty regime? To what extent are they allowed to participate in the Meetings of States Parties and the Review Conferences? We show that the role of NGO’s has increased over time and we analyze their role in the policy making process. Third, based on resource exchange theory we explain why the role of the NGO’s within the BTWC increased. We put forward the argument that the absence of a treaty organization in combination with the rapid developments in the life sciences makes cooperation between NGO’s and Participating States in the BTWC vital for accomplishing the goals of the treaty. Resource exchange theory Resource exchange theory explains why (in general) in the last few decades IGO’s became increasingly open to NGO’s. Resource exchange theory was developed in organization sociology in order to explain why organizations voluntarily exchange material and/or immaterial resources (Kruck 2011: 13; Bouwen 2002: 368; Steffek 2013: 9). The theory is firmly grounded in a rational actor approach in which cooperation takes place because actors expect to mutually benefit from their interactions. When applied to the IGO-NGO relationship the basic argument of the theory is that NGO’s exchange their material and immaterial resources (such as expertise or legitimacy), for participation in the IGO (Raustiala 1997; Nölke 2000; Brühl 2003; Pfeffer & Salancik 2003; Mayer 2008; Kruck and Rittberger 2010; Kruck 2011; Rittberger, Zangl and Kruck 2012: 25). 3 Participation is often conceptualized as access to decision-making processes in order to influence policy outcome. Rittberger, Zangl and Kruck (2012: 25) mention two drivers for this exchange. First, the compatibility of the NGO’s’ goals with those of the IGO and, second, the extent to which the IGO is dependent on the resources these non-state actors have to offer. The more essential and the less replaceable these resources are, the more willing the IGO is to grant access to the NGO. A more elaborate model of resource exchange between IGO’s and NGO’s is offered by Steffek (2013). He distinguishes between pull factors and push factors causing cooperation and connects these factors to the different phases of the policy process. Drawing on public policy literature, Steffek identifies an international policy-cycle consisting of six phases: agenda-setting, research and analysis, policy formulation, policy decision, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. The push and pull factors are connected to these six phases. The pull factors are IGO-centered and explain why an IGO would cooperate with a NGO. Steffek mentions four concrete reasons why an IGO would pull a NGO in: to identify emerging issues; to acquire additional expertise, to help with implementation and to help monitoring compliance. These reasons align with four concrete phases from the policy cycle (i.e. agenda-setting, research and analysis, implementation and evaluation). The model thus stipulates that IGO’s are not interested to pull NGO’s in in the policy formulation or policy decision phase. NGO’s, however, push for cooperation in all six phases. Six reasons are identified by Steffek why NGO’s seek collaboration: to influence the agenda, to inform the research process and/or seek financing for the provision of expertise, to influence the policy formulation, to 4 influence the policy decisions, to seek financing for the implementation of projects and to assure compliance. As noted above, important element of the Steffek’s framework is that whereas NGO’s seek to influence the policy formulation and policy decisions of IGO’s, IGO’s try to avoid this. Steffek identifies an intergovernmental core of decision making which is protected against NGO influence. Two qualifications are necessary. First, whereas the policy phase model suggests that decisions are taken in the decision making phase, in reality decisions are often shaped in the phases preceding it. Although it is plausible that IGO’s keep NGO’s far from the formal decision making phase, the question is how important this is in terms of NGO influence. Second, and more importantly, for the policy formulation phase the intergovernmental core might exist in many IGO’s, but might also be absent in other forms of multilateral cooperation. In less formal international settings the intergovernmental core might be less strong. Evidence from the antipersonnel landmines and cluster munitions negotiations suggest that NGO’s have been pulled in by states during the policy formulation and policy decision phase. Even though NGO’s did not have a formal vote in Ottawa or Oslo, it would be unthinkable that States Parties would have ignored the preferences of NGOs. In these specific cases one could even argue that through their alliance with middle powers which were sympathetic to a ban of these weapons, such as Norway, Canada and Belgium, they indirectly had a strong vote in the policy formulation and decision making phase. In our paper we adopt the Steffek’s framework for investigating whether and how resource exchange took place between States Parties and NGO’s. Based on resource 5 exchange theory, we expect that NGO’s have gained more access to the BTWC in recent years. Especially with the recent advancements made in life sciences (such as biology, bio-nanotechnology, and genetics). Because of these developments there is a growing concern about the ability of the BTWC to deal with new proliferation challenges. Therefore, we expect that with the advancements made in life sciences the BTWC has become increasingly dependent on non-governmental organizations (NGO) such as scientific organizations and industry to remain effective as a multilateral institution. Resource exchange theory suggests that this would have resulted in increased access of NGO’s to the BWC in the form of substantial participation in the Meetings of States Parties and the Review Conferences. We specifically look at the extent to which NGO’s within the BTWC are pulled in during the policy formulation phase. Departing from the notion that the more dependent an IGO is, the more it pulls NGO’s in, we hypothesize that due to the absence of a treaty organization and the complex technical nature of biosecurity, NGO’s are pulled in during the policy formulation phase. NGO’s in the BWC The BWC focuses on preventing states from developing biological weapons. Negotiations on the BTWC started in 1969 because of a renewed interest in controlling chemical and biological weapons. It helped that biological weapons were considered to be abhorrent, but increasingly also of limited military relevance (Van der Bruggen and Ter Haar, 2011: 22). The treaty entered into force in 1975 without a verification system or implementation agency. An attempt was made to set up an Organization on the Prohibition of Biological weapons (OPBW) at the beginning of the 21st century, but it failed. As a result it is difficult to enforce compliance and 6 therefore the success of the BTWC mainly depends on cooperation, transparency, and confidence building measures among the States Parties in cooperation with other international institutions (such as the World Health Organization), and NGO’s. In this paper we consider NGO’s to be ‘private voluntary organizations whose members are individuals or associations that come together to achieve a common purpose’ (Karns and Mingst 2010: 8). The definition includes both non-profit and profit oriented organizations (such as representatives from industry). Within the BTWC no distinction is made between different kinds of NGO’s in the lists of participants of meetings. For analytical reasons we distinguish between science NGO’s (universities and research institutes), advocacy NGO’s, and business and industry NGO’s. Examples from the first category are Harvard, Sussex and Bradford University. In the 1990s they launched the Harvard Sussex Program (HSP, an inter-university collaboration for research, communication and training in support of informed public policy towards chemical and biological weapons) and the Bradford Project on Strengthening the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention. Both programs are characterized by long and thorough research conducted by a staff of experienced researchers, always together with a generation of young scientists. Another example in this category is the Inter Academy Panel on International Affairs (IAP). The IAP was launched in 1993 as a global network of science academies. Its primary goal is to help member academies work together ‘to advise citizens and public officials on the scientific aspects of critical global issues’ (Inter Academy Panel 2013). Since 2004, the IAP has been actively involved in the issue of the relationship between security 7 and life science research. In that year a Biosecurity Working Group (BWG) was established with the Academies of China, Cuba, Nigeria, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States. The BWG has developed a series of activities to stimulate discussion on biosecurity. The second category are non-profit advocacy organizations. These organizations participate in the treaty regime in order to support the norm against the possession and use of biological weapons. Examples are the Bio Weapons Prevention Project (BWPP) and the Verification Research, Training and Information Centre (VERTIC). The BWPP “was launched in 2003 by a group of non-governmental organizations concerned at the failure of governments to fortify the norm against the weaponization of disease. [The] BWPP monitors governmental and other activities relevant to the treaties that codify that norm.” (Bio Weapons Prevention Project 2013). The BWPP’s website (www.bwpp.org) publishes reports, background information on technical and political issues and other relevant documents that are of interest to all politicians, diplomats, scientists and concerned citizens. VERTIC is an independent, non-profit making charitable organization. Established in 1986, VERTIC supports ‘the development, implementation and verification of international agreements’ (VERTIC 2013). VERTIC is financially supported by some Western governments and has a working area that is broader than that of Biological Weapons. Finally, an example from the category of business and industry NGO’s is Pharmaceutical and Research and Manufactures of America (PhRMA). Strikingly, business and industry NGO are largely absent in the BTWC meetings. They are occasionally present, like when negotiations were held about a verification protocol, 8 but even then they took little effective action to influence the States Parties (Littlewood 2005: 208). Also, an industry panel was organized during the Seventh Review Conference in 2011 (BWPP 2011c). But in general business and industry NGO’s play a small role in the treaty regime, which stands in large contrast with the substantial role of business and industry in the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. NGO’s participate in all formal meetings of the convention. Hence NGO’s participate formally as observers in the quinquennial Review Conferences and in the annual Meeting of States Parties. Second, NGO’s participate as ‘Guests of the Meeting’ in the annual Meetings of Experts. The Meeting of Experts consists of representatives from States Parties, representatives of IGO’s (such as the World Health Organization, WHO, the UN and the Organization on the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, OPCW), and NGO’s. The topics to be discussed by the experts are determined by the preceding Review Conference. At the Seventh Review Conference in December 2011, for example, the States Parties decided that developments in the field of science and technology related to the BTWC should be one of the three topics to be discussed in the intersessional meetings. Although NGO’s are allowed to participate, it is important to note the difference between the status of IGO’s and NGO’s within the rules of procedure of the Meetings of Experts. Whereas IGO’s are automatically entitled to participate as observers, NGO’s can only formally participate upon invitation of the Chair of the Meeting of States Parties. They are invited as ‘Guests of the Meeting’ to speak in a particular part of the programme. NGO’s which are not invited are able to participate in the informal sessions only (BWC Implementation Support Unit 2012). 9 In general, NGO’s are only allowed to attend informal, public meetings within the BTWC. In practice however, the BTWC meetings have become more open to NGO’s in recent years. In the intersessional process (the Meetings of States Parties and the Meeting of Experts), NGO’s are increasingly allowed to participate in meetings which were previously off limits. During the Prepatory Committee (PrepCom) of the 2011 Review Conference a (for NGO’s closed!) debate took place in which the role of civil society was discussed. This discussion was organized in reaction to a proposal from the Chair, the Dutch ambassador Paul van den Ijssel, to allow NGO’s to participate in the upcoming Seventh Review Conference unless States Parties would explicitly object. According to the Chairman this would confirm the practice which had evolved from 2008 onwards to allow NGO’s to attend all meetings in the intersessional process. The final outcome was very different: NGO’s would not be allowed to attend the Review Conference meetings unless the States Parties would explicitly agree to grant access (BWPP 2011a; BWPP 2011b). Actual participation during the Review Conference in December 2011 was limited to public sessions, because no decision was taken to allow NGO’s in. The PrepCom debate about the role of NGO’s and the increased openness during the intersessionals are evidence of a process of resource exchange in which NGO’s may participate in an international treaty regime in exchange for their expertise. In the next section we analyze the push and pull factors which motivate States Parties and NGO’s within the BTWC to increasingly cooperate. 10 Push and pull factors within the BWC Having described the role of NGO’s in the BTWC in general we proceed to a more specific analysis of the push and pull factors explaining cooperation between the States Parties and NGO’s. To what extent do we observe resource exchange in the different phases of the policy cycle? Let us start with some general remarks. At first sight it seems that the intersessional process as it started in 2002, is an almost perfect example of the push and pull model as described by Steffek. Even more, the intersessionals can be seen as a structure through which NGOs become institutionalized within the BTWC regime. However, some disclaimers should be made about the relevance of the interessesional process and hence the influence of the NGO’s within the regime. First, this new intersessional structure was set up as a means to ‘save’ the BTWC. The treaty regime got in an existential crisis after the failure to reach agreement on a verification regime in 2002. After this failure, the incumbent chair of the BTWC, the Hungarian ambassador Toth, explored the options for an alternative to the verification protocol. The lowest common denominator among the States Parties proved to be the intersessional process. The annually recurring Meetings of States Parties and Meetings of Experts were accepted by all members of the BTWC, but only in combination with the provision that no decisions could be taken during the intersessionals. Second, certainly in the first few years of the intersessional process the role of NGO’s was very limited. Even the Meeting of Experts was more a meeting of diplomats than a true meeting for experts and NGO’s. Many experts were in one way or another 11 linked to the delegations of States Parties and thus their independence can be questioned. After some years, however, the possibilities for independent NGO’s to fully participate in the Meetings of Experts increased. Third, the States Parties of the BTWC are still organized according to the divisions dating back from the time of the Cold War. There are three groups of states: the Western group (including Japan, Australia, New Zealand), the Eastern group (the former communist Eastern Europe) and the Non Aligned Movement group (consisting of most Asian, African and Latin American states). Not surprisingly, the Western group is most interested in the input of NGO’s. Many states of both other groups look with less enthusiasm to the increasing role of NGO’s in the BTWC. This attitude is reflected in the participation of NGO’s from these States Parties: there are almost none. Almost all NGO’s come from states from the Western Group. In spite of these qualifications, it is clear that the role of NGOs has increased. How does the relation between NGO’s and the BTWC fit the model of Steffek? As said before, he mentions four concrete reasons why an IGO would pull a NGO in: to identify emerging issues; to acquire additional expertise, to help with implementation and to help monitoring compliance. Furthermore he argues that IGO’s are not interested to pull NGO’s in in the policy formulation or policy decision phase. Below we apply this model to the BTWC. Agenda setting In the agenda setting phase, States Parties use NGO’s to identify new issues and NGO’s try to influence the agenda. Both push and pull factors can be observed within 12 the BTWC. The meetings of experts have developed to a forum where debate can take place on important new issues. Via the Meetings of states parties these issues can be elaborated to agenda items for the next Review Conference. Maybe even more important are the side events that take place during all BWC meetings and conferences. Most of these side events are organized by NGO’s, universities or other non-state actors. These side events have evolved to the most interesting meetings during a BTWC gathering. This because in these events issues can be scheduled for the agenda that are not debated during the official meetings, because it is too premature or too much sensitive. Diplomats and representatives of the official delegations are frequenting these meetings. Research and analysis Pull and push factors are also present in the research and development phase. Within the BTWC, the Implementation Support Unit (ISU) follows developments in science and technology. The ISU is a small three-member secretariat tasked with assisting the States Parties in implementing the decisions taken during the Review Conferences. One of the concrete tasks is to follow developments in science and technology. In preparation of the BTWC meetings, the ISU publishes reports on relevant developments. There is a growing involvement of scientific experts that are asked to analyse e.g. scientific and technological developments in the life sciences and its (possible) effect on the implementation of the BTWC. Some universities (such as Bradford and Exeter in the UK) have specialized departments for research on the field of biological weapons. They provide solicited and unsolicited advice to the BTWC and its States Parties. In preparation of the last Seventh Review Conference the ISU developed a so called ‘think zone’ on the BTWC website, where scientists and other 13 experts could place articles and opinions. Another interesting example is the installation of a Sounding Board (consisting of governmental and non-governmental participants) by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign affairs during the preparation of the Serventh review conference (that was presided by the Dutch ambassador). Last but not least it should be mentioned that the Harvard Sussex program and CBW Events (related to BWPP) published a very elaborate and complete Briefing Book for the Seventh Review Conference. This Book of more than 600 pages encompasses the text of all relevant treaties, BTWC documents, UN documents and documents of other organisations (Harvard Sussex Programm and CBW Events 2011). The UK government paid for it, but there was cooperation of other states, including nonWestern states such as Russia. Policy formulation In contrast to what Steffek’s model suggests, there are both push and pull factors in this policy making phase. As explained above, the intersessional meetings are a combination of Meetings of States Parties and Meetings of Experts. During these meetings NGOs and States Parties jointly identify new issues and present possible courses of action. Since 2008 NGOs have continuously participated in all intersessional meetings. Since its inception in 2002, the intersessional process has had a large influence on the discussions during the Review Conference. It often produced concrete proposals. Both States Parties and NGO’s benefit from this and as a result both push and pull factors are present. Although on average it is mainly states from the Western Group which are in favour of NGO participation, even States Parties from the Eastern Group 14 and from the NAM, which are generally critical of involving NGOs during the Review Conferences, accept the NGO role during the interesessionals. During the above mentioned discussion about the role of civil society in the Seventh Review Conference, some countries were against NGO involvement, but at the same time made positive remarks about NGO participation in the interesessional process (BWPP). Further, during the Review Conferences, most delegates are willing to share information about closed sessions with the NGO community. Since 2006 the BWPP BWPP publishes daily reports during BWC meetings with information on the most important debates and developments. The way in which these reports are prepared and spread shows that there is a close and harmonious relationship between the BWPP and many official delegates and representatives of the BTWC. The states parties involved share a common interest in making the BTWC process as transparent as possible. As the formal diplomatic procedures and rules do not allow for the daily publication of frank reports, all the parties involved agree to this information being spread in the daily reports of the BWPP, which does not have any formal status. Policy decision In this phase of the policy process we do not observe any pull factors. The 2011 PrepCom discussion about allowing civil society into formal meetings was not tailored towards allowing them to have a vote. Thus, within the BWC there is an intergovernmental core which is indeed protected against NGO influence. An example of this core is the Committee of the Whole during Review Conferences. This committee has indeed as its task bringing all interventions and discussions together in preparing a final declaration of the review Conference. This final declaration is the guideline for the BTWC policy in the next period of 5 years and that is considered to 15 be too important and sensitive to involve NGO’s in the decisions. Looking at the recent history of the BTWC it can be understood that States Parties are a bit reticent in involving non state parties. The equilibrium in the new structure is the result of a compromise between states with sometimes very different views and opinions. Diplomats are too careful people to take the risk of destroying this equilibrium. Moreover, what they can win by inviting NGO’s is already paid out in the other phases. NGO’s with the BTWC seem to acknowledge and accept this, because there are no significant attempts to get access to the decision-making phase. Policy implementation It is important to determine that we hardly can speak of a BTWC policy. The most important policy decision has never been taken: installing a verification regime. As a result the BTWC has no institutional backing to execute its policy. There is only the (very competent but very small) ISU of three (sic) persons. As far as can be spoken of policy it regards voluntary measures such as filling in forms on confidence building measures. But these are activities that are undertaken by individual States Parties and not by the BTWC as such. States Parties are therefore the most important policy implementers. Nonetheless, the mandate of the ISU allows for cooperation with NGOs. In addition, VERTIC plays an important role in implementation. It runs a National Implementation Measures (NIM) Programme, which includes assistance with legislation. Article IV of the BTWC obliges each States Party to ‘take any necessary measures to prohibit and prevent the development, production, stockpiling, acquisition or retention of biological weapons in its territory and anywhere under its 16 jurisdiction or control’. This implies for example national legislation criminalizing the activities mentioned in Article IV. Quite a few States Parties lack the necessary knowledge and/or financial resources to implement this commitment. VERTIC than ‘(..) offers assistance with legislative drafting for BWC obligations, remotely or in capitals, at no cost. VERTIC assesses the comprehensiveness of existing national measures, identifies gaps, and proposes approaches to fully implement the BWC, including amendments to existing legislation, a single issue law or omnibus legislation to cover several CBRN treaties and related legal instrument’ (VERTIC 2013). Policy evaluation As there is no much policy on the BTWC level, evaluation is not the most important element in BTWC meetings. Of course some States Parties stress the importance of carrying out the Confidence Building Measures (CBM’s), and they keep pressing states that are not filling in these CBM-forms. However, one of the reasons that the enthusiasm for participating in the process is so limited, is that there is no follow-up to the CBM’s at all. The forms are to be uploaded to the confidential space of the BTWC-website, and that is it. Attempts - as during the most recent Meeting of Experts (August 2013) - to relocate the forms to the public space (which would increase transparency) and to organize sessions for debating the CBM’s were blocked. Most of the opposing states belonged to the group of non-respondents. In the field of policy evaluation some NGO’s are trying to influence the debate. During the last Meeting of Experts King’s College (London) presented a policy brief on how to deal better with CBM’s (Lentzos 2013). Moreover, BWPP presents a Bio 17 Monitoring Report which, modelled after the Landmine Monitor and Cluster Munitions Monitor Reports, aims at assessing treaty compliance (Bio Weapons Prevention Project 2011d). Why did the role of NGO’s increase? Above we argued that the role of NGO’s has increased and that resource exchange takes place in almost all phases of the policy cycle. Was this due to an increased dependence of the BWC on NGO-expertise? In other words, to what extent do we observe resource exchange? Four key developments explain the increased role of NGO’s from a resource exchange perspective. The first development is a general trend of growing NGO participation in global governance. The BTWC is far from immune for this trend and NGO participation may be partly explained by this. Secondly, the failure in the Summer of 2001 to establish the OPBW meant that States Parties started to look for alternative ways to strengthen compliance with the treaty (McLeish and Trapp 2011: 538) and they needed the expertise of NGO’s to do this. Thirdly, as we already referred to above, the developments in the life sciences make involvement of NGO’s more important. It is hard for States Parties to keep on track with the advancements. A final and fourth explanation is that compared biological non-proliferation regime is not – as e.g. nuclear proliferation regime – in the hard core of international security policy. It is a relatively less political salient issue, which makes NGO involvement probably also less problematic. Having said this, we emphasize that the increased NGO involvement is not unchecked and in many ways limited. It surely is better than in some other arms control regimes, but also much less than it could be – and in the eyes of many involved NGO’s – 18 should be. Furthermore, it could be argue that the role of NGO’s becomes even less important if ‘real’ issues are at stake. This was shown by the recent case of scientific development regarding the H5N1 (birdflew) virus. This case study falls beyond the scope of our paper, so we limit us to the observation that States Parties took decisions without consulting, and even by excluding, NGO’s. Also interesting is that this debate also took place outside the BTWC circuit. Conclusion In this paper we analyzed the role of NGO’s within the BTWC. They are hardly agents of contestation. Instead, where they can they collaborate closely with the States Parties of the BTWC. There is substantial cooperation which can explained by resource exchange theory. The NGO’s provide expertise and in return they have access to the treaty regime. The general trend of increased NGO participation, the absence of a treaty organization, the advances in the life sciences and the relative low importance which is given to biological weapons explain this. Most push and pull factors identified by Steffek have been observed. However, we found that, contrary to the expectations of Steffek’s, NGO’s are also pulled in during the policy formulation phase. This first provisional analysis seems to show that the intergovernmental core only exists within the policy decision phase. References Bio Weapons Prevention Project (2011a), PrepCom report #2: The BWC Preparatory Committee: the opening day, 14 April. Available at: http://www.bwpp.org/documents/PC11-02.pdf (visited 28 August 2013). Bio Weapons Prevention Project (2011b), PrepCom report #3: The BWC Preparatory Committee: the second and final day, 15 April. Available at: http://www.bwpp.org/documents/PC11-03.pdf (visited 28 August 2013). 19 Bio Weapons Prevention Project (2011c), RevCon report #5: Industry and Posters: the 4th day of the Review Conference, 9 December. Available at: http://www.bwpp.org/documents/RC11-05.pdf (visited 28 August 2013). Bio Weapons Prevention Project (2011d), Bioweapons Monitor 2011. Available at: http://www.bwpp.org/documents/BWM%202011%20WEB.pdf (visited 28 August 2013). Bio Weapons Prevention Project (2013), www.bwpp.org (visited 28 August 2013). BWC Implementation Support Unit (2012) Communication from the Chairman of the BWC. Available at: http://www.unog.ch/80256EDD006B8954/(httpAssets)/FA64FCEB2F58B968 C1257A24003D4F7C/$file/Chairman+letter+to+SPs+21+June+2012+(with+a ttachments)-+as+sent.pdf Bouwen P. (2002) Corporate lobbying in the European Union: the logic of access. Journal of European Public Policy 9: 365-390. Brühl T. (2003) Nichtregierungsorganisationen als Akteure internationaler Umweltverhandlungen. Ein Erklärungsmodell auf der Basis der situationsspezifischen Ressourcennachfrage, Frankfurt/M.: Campus. Dany C. Global Governance and NGO Participation. Shaping the information society in the United Nations, London and New York: Routledge. Docherty B. (2009) Breaking New Ground: The Convention on Cluster Munitions and the Evolution of International Humanitarian Law. Human Rights Quarterly 31: 934-963. Harvard Sussex Programma and CBW Events (2011), Briefing Book. Seventh BWC Review Conference. Available at: http://www.cbw-events.org.uk (visited 28 August 2013). Inter Academy Panel 2013, http://www.interacademies.net/CMS/About.aspx (visited 28 August 2013). Karns MP and Mingst KA. (2010) International Organizations. The Politics and Processes of Global Governance, Lynne Riener: Boulder. Keck ME and Sikkink K. (1998) Activists beyond borders: Advocacy networks in international politics, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. Keck ME and Sikkink K. (1999) Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics. International Social Science Journal 51: 89-101. Knopf JW. (2012) NGOs, Social Movements, and Arms Control. In: Williams REJ and Viotti PR (eds) Arms Control. Volume I. History, Theory and Policy. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 169-194. Kruck A and Rittberger V. (2010) Multilateralism Today and its Contribution to Global Governance. In: Muldoon JPJ, Aviel JF, Reitano R, et al. (eds) The New Dynamics of Multilaterlism. Diplomacy, International Organizations, and Global Goverance. Boulder: Westview Press, 43-65. Kruck A. (2011) Private Ratings, Public Regulations Credit Rating Agencies and Global Financial Governance Basingstoke: Palgrave. Lentzos, F. (2013) Policy Brief. Hard to Prove. Compliance with the Biological Weapons Convention. London: King’s College Littlewood J. (2005) The Biological Weapons Convention. A Failed Revolution, Aldershot: Ashgate. Mayer P. (2008) Civil Society Participation in International Security Organizations: The Cases of NATO and the OSCE. In: Steffek J, Kissling C and Nanz P (eds) Civil Society Participation in European and Global Governance. A Cure for the Democratic Deficit. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 116-139. 20 Mcleish, C. and Trapp, R. (2011) The Life Sciences Revolution and the BWC. Reconsidering the Science and Technology Review Process in a PostProliferation World. The Non-Proliferation Review 18: 527-543. Nölke A. (2000) Regieren in transnationalen Politiknetzwerken? Kritik postnationaler Governance-Konzepte aus der Perspective einer transnationalen (Inter)Organisationssoziologie. Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen 7: 331358. O'Brien R, Goetz AM, Scholte JA, et al. (2000) Contesting Global Governance : Multilateral Economic Institutions & Global Social Movements. Pfeffer J and Salancik GR. (2003 [1978]) The External Control of Organizations. A Resource Dependence Perspective, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Raustiala K. (1997) States, NGOs, and International Environmental Institutions. International Studies Quarterly 41: 719-740. Rittberger V, Zangl B. and Kruck A. (2012) International Organization, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Short N. (1999) The Role of NGOs in the Ottawa Process to Ban Landmines. International Negotiation 4: 481-500. Steffel J. (2012) Explaining cooperation between IGO’s and NGO’s – push factors, pull factors, and the policy cycle. Review of International Studies FirstView: 1-21. Van der Bruggen K. and Ter Haar B. (2011) The Future of Biological Weapons Revisited. A Concise History of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention, The Hague: Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. VERTIC (2013), http://www.vertic.org (visited 28 August 2013). Williams J, Goose SD and Wareham M. (2008) Banning Landmines. Disarmament, Citizen Diplomacy, and Human Security. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 21