Magazines in a Supermarket Economy

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

Magazines in a Supermarket Economy

The Opportunities & Challenges Facing Publishers

Wessenden Marketing

WESSENDEN MARKETING

Littleworth House, Tuesley Lane, Godalming, Surrey GU7 1SJ

Tel. 01483 421690 Fax. 01483 427089

Email. info@wessenden.com

Website. www.wessenden.com

Page 1

Magazines in a

Supermarket Economy

The Opportunities & Challenges Facing Publishers

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

REPORT CONTENTS

Page

Background and Brief

Preface: The Tesco £2bn Profit

Management Summary

2. BEYOND THE SHELF

Supermarkets blurring the boundaries

3. ON THE SHELF

Supermarkets selling magazines

4. BEHIND THE SHELF

Supermarkets in context

3

13

23

57

5. THE PUBLISHER RESPONSE 85

Wessenden Marketing

Page 2

Section 1

INTRODUCTION

Wessenden Marketing

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

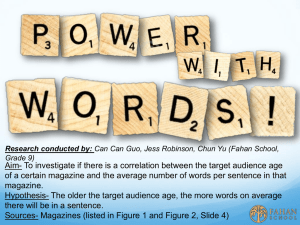

1.1 Background

1.2 Brief

1.3 Preface: The £2bn Tesco Profit

Page 3

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

1.1 Background

The major supermarket groups are coming to be regarded as one of the biggest threats to the future of UK consumer magazine publishing.

Much of the current supermarket debate has focused on supply chain issues and the erosion of publisher margin as a result of growing grocery power.

Yet while the grocers can use their power ruthlessly, this power springs from and is devoted to the ceaseless pursuit of customer satisfaction, rather than simply to destroying the competition or squeezing suppliers.

To understand the supermarkets’ agenda and their future direction is to understand (1) the business priorities of a key partner, but also (2) what the consumer actually wants. In a world where consumer shopping patterns are being shaped by and reflected in the supermarket offer, a deeper understanding of the supermarket sector should highlight where the whole consumer market is heading.

The “supermarket economy” is the true context for magazine publishers’ activity in the future and it touches the whole publishing model, not just circulation strategy. It also affects all magazines, not just those actually stocked by the major supermarket groups, as the general consumer environment is being shaped by these trends.

1.2 Brief

The brief is to map the environment for consumer magazine publishing with reference to the supermarkets’ agenda, through a consolidation, review and analysis of currently available research and trends.

What are the options and the challenges facing publishers as a result? Can publishers work with the supermarkets rather than be crushed by them? How will all this impact on the publishing model of the future?

While supply chain issues are to be referenced, they do not form the central focus of this particular report.

The aim of this project is to provide an overview of the issues which supermarkets present: an outline agenda for more detailed work and research in the future and the context for ongoing industry projects.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 4

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

1.3 Preface: The Tesco £2bn Profit

Although it was well-trailed and well-prepared in advance, the announcement of Tesco’s full year trading profit (52 weeks to Feb

2005) still caused a public stir and represents a major milestone in

UK retailing: Tesco has become the first UK retailer to post profits of more than £2bn.

The results came two weeks after TNS data showed that the retailer’s share of the grocery market had broken through 30% for the first time.

Apart from the sheer scale of the profit, Tesco’s announcement underlines a number of key trends detailed in this report.

Perhaps most significant is the growing importance of what Tesco calls the three “growth businesses”:

1. Non-food (20% of total UK sales) with overall sales growth of

17%. The fastest growing categories were:

•

Clothing (+27%)

•

Seasonal products (+27%)

•

Stationery, news & magazines (+26%)

•

Home entertainment (+20%)

•

Health & beauty (+13%).

Consumer selling prices in non-food have been reduced by 1% year on year. This has been funded by “our growing scale and supply chain efficiency, including an increasing level of direct sourcing.” Tesco is rolling out its supply chain disciplines and practices to non-food categories generally.

Tesco, like Asda, is currently involved in testing a store format which sells no food at all in it.

Wessenden Marketing

2. International (21% of total Tesco sales). Overseas sales rose by 18.3% (on constant exchange rates) outstripping the 11.9% rise in the UK.

3. Retailing services

•

After only 12 months of operation, Tesco Telecoms

(mobiles, land lines & internet access) has 1m customers.

It is losing £4m per year, but has made an immediate market impact.

•

Tesco.com accounts for 2.4% of all Tesco’s UK sales and makes a healthy 5.0% profit margin.

•

Tesco

(700,000 up on last year) of which 1.7m are credit cards and 1.4m motor insurance policies

Together, these three areas make as much profit for Tesco as the entire business made in 1997.

Other key trends are:

Increasing profitability . Operating margins edged up slightly to

6.2% of sales. This has come from constant pressure on supply chain and operational savings.

Growth in sales space . New store openings are still a major driver of Tesco’s growth, though the underlying like-for-like sales are still very impressive. Yet growth in sales space is putting massive pressure on all its retail competitors, both multiple and independent. It also puts pressure on its own internal operations to convert that space growth into profitable sales.

UK Sales Growth

Like for Like

New Stores

TOTAL

9.0%

2.9%

11.9%

Page 5

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

Price deflation . The sales growth was volume driven.

UK Like for Like

Sales Growth

Volume

Price

Value

8.9%

0.1%

9.0%

Strip petrol sales out of the figures and the +0.1% price rise turns negative and the +9.0% value rise slows to +7.5%.

Tesco invested £230m over the year in price cuts. It has just announced a further £67m for its latest campaign, sparking an immediate response from Asda.

The ongoing mission remains entirely consumer-focused based on four key priorities for shoppers:

•

Making shopping trip as easy as possible.

•

Constantly to to help them spend

• less.

Offering of either large or small stores.

•

Bringing to complicated markets.

Tesco’s core Mission Statement remains: “Our core purpose is to create value for customers to earn their lifetime loyalty. We deliver this through our values: (1) non one tries harder for our customers and (2) we treat other people how we like to be treated.”

Owning more consumers . Analysts estimate that Tesco has picked up 1m new customers from its competitors over the last year, taking its UK shopper numbers to 13m. Customers are also spending more : average spend per visit is up by over 2% year in year.

Wessenden Marketing

All this underlines Tesco’s specific success as an operator, but also points to more general trends in the grocery market:

•

The growth of non-food.

•

The roll-out of supermarket supply chain disciplines and practices to non-food categories.

•

The importance of building share through an aggressive policy of store openings and price competition.

•

The general consumer context of price deflation.

•

The focused pursuit of the consumer.

Tesco sets the context and the benchmarks for the rest of the grocery sector.

Page 6

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

1.4 Management Summary

The major supermarket groups dominate the current consumer marketing scene. Their buying power, supply chain mastery and obsessive pursuit of the consumer make them both fascinating to observe and frightening to do business with. As a result, people have strong opinions about them:

•

The media dislike them for “homogenising” the country and for duping consumers with selective price cuts.

•

Their retail competitors criticise them for destroying all opposition and, therefore, for undermining the traditional retailing fabric.

•

Their suppliers, including magazine publishers, fear them as in their drive for margin, consistency and efficiency, they can squeeze supplier margins, strangle innovative new product development and reduce product diversity.

•

The consumer remains ambivalent, wistfully lamenting the loss of the independent retail sector while continuing to buy a wide range of goods from their convenient, wellpresented and well-stocked supermarkets.

Whether the supermarkets are responsible for shaping the modern consumer marketing climate or whether (as they would argue) they are merely responding to bigger social trends and consumer demands is a complex question. The real answer lies somewhere between the two.

In a commercial sense, the question is also probably irrelevant.

Whatever their role in where consumer marketing is now, they are at the cutting edge of that consumer marketing. Observing them has a great deal to teach any FMCG supplier, including magazine publishers.

BEYOND THE SHELF: Supermarkets Blurring the Boundaries

A clean retailer-manufacturer interface is being complicated by the increasing number of roles that the supermarkets are assuming, such as:

•

Magazine advertisers with the commercial leverage which that implies.

•

Media owners, selling “consumer contacts” via such media as in-store TV, trolley ads, direct mail etc.

•

Magazine publishers in their own right.

•

Magazine subscription agents competing with publishers’ own subscription activity.

•

Non-retail operators, competing in online activity.

•

Magazine censors, making stocking and delisting decisions on the basis of editorial issues and “taste & decency”.

•

Magazine product influencers with increasingly detailed views on such issues as on-sale dates, cover pricing, editorial positioning, etc.

While the publishing industry may be over-sensitive to some of these issues, probably the most profound and worrying is the emerging role of the supermarkets as media owners in their own right, not so much for the fact that they will be competing with publishers for advertiser budgets, but because the numerous

“customer contacts” that the supermarket media operations can offer are all part of the grocers’ relentless drive to “own” the consumer. However, rather than seeing the supermarkets purely as competitors, there may be creative opportunities for publishers and retailers to work together in partnership.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 7

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

ON THE SHELF: Magazines in Supermarkets

The supermarket operators have grown close to a 30% share of consumer magazine retail sales value, with predictions that they could in time reach 40%. This growth is based on their taking a very definite profile of magazine sectors, as detailed in the report.

It is also being accelerated by the current buoyancy in the weekly magazine market, which is driving share, with publishers’ knowledge and support, ever more quickly into the hands of the supermarkets.

It is also based on a magazine range that is wider than many actually realise and which, over the long term, has been growing.

Far from ignoring specialist magazines, the supermarkets have provided many new sales opportunities for a wide range of magazine product. Yet the supermarkets’ surprisingly deep commitment to range is also a danger in two respects:

•

Should commercial pressures force a reduction in supermarket space for magazines in the future that would have a major negative effect on the publishing industry.

•

The supermarket commitment to magazines has had a major impact on WHSmith High Street. Perhaps of even more significance than what the supermarkets choose to do themselves with their magazine offer is the ongoing stability and direction of WHSmith.

The industry needs to be clear why supermarkets want magazines . Magazines do not build consumer traffic in supermarkets. They do not offer supermarkets attractive profit margins. What they do provide is a major enhancement to the supermarket shopping experience and there appears to be a clear link between magazine purchasing and basket size. Probing more deeply into this whole area is an urgent requirement.

In perspective, the supermarkets have brought many benefits to the magazine business, which include increased sales opportunities, better standards of magazine retailing & wholesaling and more efficient supply chain processes. Yet they have undermined the positioning of WHSmith Retail in particular and they threaten to destabilise a supply chain, which for all its complexities, offers relatively open access for publishers of all sizes to an unusually large and diverse retail network .

This whole process is managed through four, interlocking interfaces.

RETAILER

Shopper

Interface

Consumer

Interface

Point of

Purchase

Business

Interface

The consumer interface bonding with the reader.

CONSUMER

PUBLISHER

. Magazine publishers are the masters of

•

Understanding and defining that bond more clearly and selling that to retailers are urgent and essential requirements.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 8

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

•

Finding more direct routes to the consumer, principally through postal subscriptions, but increasingly through on-line applications, is a priority.

The shopper interface . What matters to retailers is how and why their shoppers relate in-store to magazines as a category. Again, a more detailed understanding of this is essential.

The point of purchase . This is the real “hot spot” where all three players meet, where the sale takes place and about which the industry understands least. It is also clear that there must be more potential to develop the in-store theatre of magazines in more creative and promotional ways than is the case at the moment.

Focusing more on the consumer “front end” and on growing sales in a positive way must be the industry’s key priority.

The business interface . The supply chain “back end” has been the focus of so much of the industry’s time over the last few years.

Yet the supermarkets feel that progress on some very basic operational issues has been far too slow. The publishing industry must accelerate developments in standardising and simplifying supply chain processes if it is head off another supermarket revolt as was seen in National Distribution in 2000. Central to all this is:

•

Defining the role of the wholesaler more clearly.

•

Implementing standard key performance indicators right through the supply chain.

•

Simplifying the processes that bring the product to market without compromising control over the product itself.

•

Extending the Supermarket Code to include newspapers and magazines. This would provide an ongoing monitoring of supermarket business practices by the regulatory authorities.

Wessenden Marketing

BEHIND THE SHELF: Supermarkets in context

Supermarkets are under immense pressure . Minimal volume growth and low price inflation in their core food product categories have resulted in massive competition between the major players and in business operations which are focused on:

•

Squeezing every economy and efficiency from their supply chains.

•

Driving volume through price-driven consumer offers.

•

Building market share through acquisition.

•

Diversifying into

(1) non-food products and services

(2) more varied retail format & locations (e.g. convenience)

(3) non-retail channels (e.g. online)

(4) overseas expansion.

This makes the “supermarket sector” an increasingly complex and volatile marketplace. Behind a handful of impressive grocery retailing operations, there is a whole host of very mediocre ones, who have not got their consumer offer right, whose price positioning simply does not add up or whose supply chains are creaking badly.

This has a number of implications:

•

Publishers’ channel strategies must take account of retail multiple shares which will shift more quickly than ever before with complete retail groups potentially disappearing through acquisition or collapse.

•

Publishers cannot not treat all supermarkets in the same way.

They can differ widely in terms of their consumer offer, shopper behaviour, business processes and overall proficiency.

Page 9

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

•

Price has emerged as a key lever in the grocers’ marketing toolkit and will become increasingly important as market competition intensifies.

The importance of price raises some fundamental issues:

•

The grocers are setting general consumer expectations for the price of many consumer goods, many of which are actually seeing price deflation. In that context, there must be a limit as to how high and how rapidly magazine cover prices can rise.

•

Setting their own consumer prices on branded goods is a fundamental way in which the supermarkets manage their business. Holding on to control of the cover price is a key aspect of publishers’ continued control of the brand.

•

The various supermarket positions on price show real strategic thinking about the role that price plays in their branding. Publishers must show the same level of strategic thinking not just in setting retail cover prices, but in balancing subscription prices versus retail prices.

Linked to price is the pivotal role of own-label products in the supermarket process of weakening the position of the manufacturer.

The fact that magazines are so difficult for retailers to “own-label” is probably the single most important asset that publishers have in their negotiations with supermarkets. It is a strength which should never be underestimated.

Magazines are an important part of the supermarket diversification into non-food . Yet this also means that magazines are fighting to hold their current space allocations in-store against an everexpanding array of non-food products. The publishing business must become much smarter in the arguments it puts forward to hold its current position within the supermarkets.

The trend towards supermarket diversification has two other implications:

•

The supermarkets’ own knowledge about an ever-widening product range must be stretched. This opens up an opportunity for proactive suppliers to have more input into the retailers’ management of the category, especially a category as complex and fragmented as magazines.

•

Consumer research shows that the supermarkets have a difficult balancing act to set their drive for a wider product range against shopper concerns that they might lose their food focus. Blurring the core offer has been the undoing of some major retailers in the past and could be the undoing of some major grocers in the future.

Central to the way in which the supermarkets operate is a constant streamlining of supply chain processes and costs:

•

Publishers must attempt to simplify and open up the magazine supply chain without conceding too much control.

•

Publishers must show the same focus on supply chain processes that the supermarkets have.

•

Publishers must try to understand and improve the in-store processes that the supermarkets are seeking to manage.

Consumer shopping patterns are becoming more complex and fragmented. Understanding much more clearly where magazines fit into these trends is central to defending and growing sales in supermarkets.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 10

THE PUBLISHER RESPONSE

The obvious response to growing supermarket power is for publishers to develop non-supermarkets sales, but the industry has not yet devoted enough resource to doing so.

These non-supermarket channels include:

•

Other existing magazine retailers.

•

New, non-traditional magazine retailers.

•

Postal subscriptions

•

Electronic delivery of editorial.

The report also suggests a range of more detailed action points, ranging from increased investment in consumer research through to developing a more defined strategy for the wholesale sector.

Wessenden Marketing

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

CONCLUSIONS

Standing back from the detail, the report suggests some key conclusions.

Publishers have good reason to be confident.

The power of the magazine brand with the consumer lies at the core of magazines’ negotiating position with supermarkets which is actually stronger than many publishers fear it is.

Supermarket power in such a fast-moving and pressured environment is much more volatile and fragile than it first appears.

Retail brands which are based so heavily on price are actually very vulnerable. This can make them more dangerous and erratic to deal with as the recent past of Safeway and Sainsbury demonstrates.

Publishers have no reason to be complacent and there needs to be real action in a number of areas:

•

The “Magazine Message” needs to be sold to retailers. This message needs to be supported by detailed consumer research insights and by a consistent approach at an industry level.

•

Although improvements have been made, senior publishing management need to demonstrate as sharp a focus on circulation issues as they have shown on advertising issues.

•

Publishers have abdicated responsibility for too many important decisions about the future of the supply chain to links lower in the chain, particularly to wholesalers, who have their own priority list which can be subtly different to those of publishers.

Page 11

•

The supermarkets have a great deal to teach the publishing industry about:

(1) taking apart and then reassembling their own business models and those of the partners they work with.

(2) building and actioning a long-term strategy beyond the six month ABC horizon.

(3) the relentless pursuit of the consumer in order (to use

Tesco’s phrase) “to earn their lifetime loyalty.” Continuous learning and continuous improvement lie at the core.

•

Publishers need to spend real resource in developing nonsupermarket sales channels.

•

As consolidation takes place in every link in the supply chain, how much scope is there for further consolidation in publishing and would that stifle the industry’s essential creativity?

It is imperative for publishers to engage with the supermarkets .

To refuse to engage; to avoid transparency in the supply chain; to slow down changes to supply chain processes; to side-step contentious issues or confrontation: all these things will do will be to build up the supermarkets’ already significant frustration with a

Wessenden Marketing

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY complicated product category and to force radical change, which is what almost happened with National Distribution in 2000. To engage with the supermarkets has its dangers; but to refuse to engage has many more.

Yet perhaps the biggest threat to the newstrade structure is the uncertain future direction of WHSmith Retail . The current situation is the direct result of the growing share of the grocers in the magazine business. The full consequences of that may still have to be played out.

Page 12

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

Section 2

BEYOND THE SHELF

Supermarkets blurring the boundaries

2.1 Supermarkets as media owners

2.2 Supermarkets as publishers

2.3 Supermarkets as advertisers

2.4 Supermarkets influencing advertisers

2.5 Supermarkets as subscription agents

2.6 Supermarkets as censors

2.7 Supermarkets as product influencers

2.8 How supermarket power grows

2.9 Managing supermarket power

2.10 The Bain study of Wal-Mart

2.11 Conclusions

Wessenden Marketing

Page 13

Much of the current supermarket debate within the magazine industry has focused on “on-the-shelf” issues: in other words, how to deal through the supply chain with a retail channel which is growing its market share very rapidly.

Yet some of the more worrying and far-reaching trends are taking place “beyond the shelf”, as the major grocers develop roles and take initiatives beyond their traditional retailing operations.

There are growing concerns among publishers that the commercial interface between supplier and retailer is becoming confused and blurred due to a number of factors.

While some of these concerns may be alarmist, they are undoubtedly adding to the tensions in the supply chain.

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

2.1 Supermarkets as media owners

In 1977, 3 spots on TV could achieve an 80% coverage of UK adults and the top three supermarkets had a 25% market share. In

2005, 65 spots on TV are required to achieve the same coverage and the top four retailers have more than 75% market share. As media has fragmented, retail has consolidated. Now 95% of UK consumers visit a supermarket on average 1.7 times a week.

In April 2005, Walmart USA announced that the reach of its in-store

TV screens made it the fifth largest TV network in the USA after

NBC, CBS, ABC and Fox. With a monthly reach of 130m consumers shopping its aisles, it has become a powerful media owner in its own right. The retailer is currently upgrading the system which broadcast movie previews, clips of sports events & concerts and advertisements for consumer products on sale instore. The upgrade involves installing 600 42-inch high-definition screens by December 2005 with the system being rolled out to all

2,600 Wal-Mart stores in the USA.

“Supermarket media” is not a new phenomenon. In-store promotions have always been a staple of grocery marketing activity, trying to influence the consumer at the point of purchase. They have also been a very useful revenue stream, which is estimated currently to be worth in the region of £50m per year (in-store media only).

In-Store Retail

Media Spend

Year

2001

2002

2003

2004

Source: Concord

Spend

(£m)

26.8

34.4

42.0

50.0

Wessenden Marketing

Page 14

Yet several factors have more recently come into play:

•

In response to customer feedback, the major retailers recognise that they need to “declutter” their stores to make the shopping trip more streamlined and less confusing. This has resulted in the amount of point-of-purchase signage being cut back by up to 50% with a concentration on fewer, bigger promotions.

•

Store compliance with in-store promotions has become a major issue with recent POPAI research suggesting that only

53% of the point-of-purpose material delivered to supermarkets actually makes it to the shop sales area.

•

With massive consumer traffic, the major retailers have recognised the media opportunities that their stores themselves can offer.

•

Meanwhile, traditional media are fragmenting in their reach and there is a growing consumer apathy to traditional sales messages.

•

Add in the accountability and measurability of in-store media, particularly when it is linked to loyalty card data, and the supermarkets are developing a convincing media case.

The major grocers have set up their own media departments to sell their “media opportunities” to external clients. These opportunities are distinct from normal in-store trade marketing activity and represent a real push to get access to suppliers’ mainstream advertising budgets in addition to their trade marketing budgets.

The real coup for the supermarkets in being taken seriously as a media outlet is when they begin to pick up ads for products which are not sold in-store (e.g. car advertising).

Wessenden Marketing

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

The media options fall into three basic areas, each with their own ratecard:

1. AT HOME

•

Inserts in loyalty card statements

•

Direct mailshots to loyalty card members

•

Customer magazines (see “Supermarkets as Publishers” on the next page)

•

Specific user groups and clubs (e.g. Tesco Wine Club, Tesco

Baby & Toddler Club)

•

Websites

2. OUT OF STORE

•

Posters on the sides of delivery vans and lorries

•

Poster sites around the outside of stores

•

Sampling stands in car parks

•

Ads on petrol pump nozzles

3. IN STORE

•

In-store plasma TV screens

•

Trolley and basket ads

•

Floor posters

These new media options are much more than a cynical means of developing more retailer revenue, although they do serve that purpose. They are also part of the supermarkets’ relentless pursuit of the consumer’s lifetime loyalty, trying to influence their buying decisions at every step along the shopping process from the home right through into the store. Tesco refers to their media options as

“consumer touchpoints”: places and times in the consumer’s life when the retailer can make contact and have an impact.

Page 15

2.2 Supermarkets as publishers

As a very specific extension of “supermarkets as media owners”, there has been a growing interest among retailers in developing their own print products, though they have had much more success in book publishing or in magazine one-shots.

Some of these projects are customer magazines rather than openmarket, paid-for publications. Here, the retailer is using the proven customer-bonding power of the magazine format to serve their own shoppers.

Title

Asda Magazine

Tesco Magazine

The Somerfield Magazine

Simply Co-op

Dec 2004

ABC (000)

2,585

2,000

1,116

1,000

% Actively

Purchased

0

0

0

0

Sainsbury's The Magazine

Waitrose Food Illustrated

340

300

97

2

Source: Supermarkets & ABC

A distinct sector is “retailer exclusives” where established magazine publishers produce titles for exclusive distribution through a particular retail chain.

True own-label publishing is actually very difficult to achieve successfully, though WHSmith Retail have done most in this area.

This underlines the importance and strength of brands in the magazine sector.

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

2.3 Supermarkets as advertisers

In 2004, the top ten supermarket chains spent a total of £224.2m in advertising, up by 15% year on year. Consumer magazines took a

6.7% share of that spend: £15.4m (Source: Nielsen Media

Research).

The table below shows how the grocers’ ad spend broke down by medium. Magazines increased their share year on year, but still remained in fifth position with TV and national and regional newspapers all increasing their shares too. Waitrose devoted more of its budget to magazines (13%) than any other grocer, followed by

Tesco (10%). The supermarkets are significant buyers of magazine ad space. Tesco is the tenth largest single advertiser in consumer magazines.

Top Ten Supermarkets Ad Spend Profile

Medium

TV

National Newspapers

Regional Newspapers

Direct Mail

Magazines

Radio

Outdoor

Internet

Cinema

TOTAL

2003

46.0%

16.3%

7.5%

9.7%

5.4%

8.7%

2004

46.7%

20.3%

7.8%

7.6%

6.7%

6.5%

5.5%

0.9%

3.8%

0.5%

0.0% 0.1%

100.0% 100.0%

Source: Nielsen Media Research

In the Spring of 2005, Marks & Spencers (M&S) and Associated

Newspapers fell out over the editorial coverage being given to the retailer in the business sections of the newspapers. M&S

(temporarily as it happened) withdrew its advertising worth in the region of £3m per year from three of Associated’s newspapers.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 16

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

While pacifiying disgruntled advertisers who have been upset by the editorial coverage given to their company is the regular task of most publishers, where that advertiser is also a retailer which sells the publications concerned, the potential for unfair “leverage” becomes a real possibility.

Having said this, it was the ruthless use of newspaper editorial coverage which was a major factor in derailing the National

Distribution plans of Tesco and WHSmith in 2001. Here editorial was used to influence a commercial retail decision. So there clearly is a willingness on both sides to blur “commercial” and “editorial” factors, which could have dangerous implications.

2.4 Supermarkets influencing advertisers

Some years ago, US magazine distributors reported a suggestion made by a major supermarket chain to lean on some of its FMCG suppliers to advertise in a specific consumer magazine in return for that magazine sharing some of the resultant advertising revenue with the retailer.

The suggestion was immediately rejected, but it highlighted the supermarkets’ growing knowledge of and interest in the publishing business model with its dual revenue streams of circulation and advertising.

2.5 Supermarkets as subscription agents

High Street retailer WHSmith has made a major impact in the postal subscription arena by selling gift subscriptions to magazines from special displays in-store. Tesco trialled a similar scheme in 2004, though with much less success than WHSmith.

Tesco has since run a much stronger promotion across 23 magazines where Tesco Clubcard vouchers can be exchanged for cut-price (75% below retail cover price) postal subscriptions. The reported subscriptions volumes exceed those of the WHSmith gift subscription operation.

Other major retailers are using their loyalty card and customer data not just to target in-store magazine promotions, but also to sell postal subscriptions to their shoppers.

While publishers are rightly pursuing these types of promotions, they are all examples of retailers beginning to take a material share of non-retail routes to market.

Postal subscriptions, one of the possible “escape routes” from retail multiple power, are actually being taken over by the retailers themselves.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 17

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

2.6 Supermarkets as censors

The range management disciplines of the major retailers are normally based on pure commercial criteria centred on the financial return on investment of their shelfspace. Yet there have recently been more instances of “taste and decency” decisions where retailers have delisted titles due to provocative covers and editorial content, mainly in the men’s lifestyle area.

The retailers claim that they are merely responding to complaints from their own shoppers and that to ignore that feedback would be both irresponsible and commercially inept: it is the shopper who is setting the decency agenda, not the supermarkets themselves, is the claim.

Tesco has issued decency guidelines which have divided opinion within the publishing community, with many seeing them as being utterly reasonable while others fear that this is the “thin end of the wedge”.

The Tesco policy statement runs: “We do not aim to be the moral guardians or censors of content, provided it remains within the law, but we do aim to deliver choice as demanded by our customers.

There is no consumer demand for “censorship” registered with our

Customer Service department.”

Tesco categorises “at risk” newspapers and magazines as those whose covers depict exposed genitalia or female nipples, the association of violence with sexual activity, the “C or F words” and male or female derogatory words. These titles will only be accepted for display if they are securely bagged in such a way as to obscure all the indecent material on the cover and to prevent access to the publication except by opening or damaging the bag.

Yet the whole issue of range editing for non-commercial reasons makes the publishing industry feel uncomfortable, especially when significant market share can be at risk dependent on subjective, and sometimes personal, opinions.

Recent examples are Sainsburys banning Front in the Spring of

2004 and Marks & Spencer deslisting Zoo and Nuts in 2005. In the

USA, Wal-Mart has lead the way by deslisting Maxim, Stuff and

FHM and by obscuring the covers of titles such as Cosmopolitan,

Marie Claire and Redbook with special screens.

2.7 Supermarkets as product influencers

The role of the retailer has changed very significantly. Big Retail is no longer the neutral purveyor of a defined range of branded goods to a defined and localised geographical community. The modern multiple retailer now specifies products for the audiences that it has consciously decided to serve.

Apart from commissioning their own-label product lines (see Section

4.11), supermarkets also have a material influence over branded consumer products too, principally in terms of consumer pricing, pack size and packaging.

The major retailers have made no secret of their desire to control magazine cover prices (usually by price-cutting) in order to manipulate sales volumes. Yet there have been reports of retailers also making suggestions about on-sale dates and editorial positioning in order to maximise sales on the shelf.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 18

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

2.8 How supermarket power grows

In other FMCG categories, retailers have exerted their power in a number of ways which were outlined to PPA members in recent presentations made by consultants Deloitte & Touche:

•

Using increasing market share to renegotiate retail margins .

•

Controlling retail selling price , which usually means cutting it. This normally involves some funding for the price cut from the manufacturer.

•

Influencing of the product.

• product range more tightly through head office

“hard ranging”.

•

Controlling through EPoS driven systems.

• frequency of deliveries to feed sales based replenishment.

•

Forcing manufacturer investment into in-store promotional activity.

•

Forcing investment as Radio Frequency Identification (RFID).

such

• supply chain savings upstream and then taking a

“share” of the savings having learned about the suppliers’ economics along the way (e.g. Factory Gate Pricing)

Some of these trends are simply unlikely ever to apply to press products, but many do. It is also impossible simply to ignore the general forces at work in the retail market.

Wessenden Marketing

2.9 Managing supermarket power

Responding to the growing influence that the supermarkets have in so many different aspects of the modern commercial world may seem a daunting, even hopeless, prospect.

Can the growth of retail multiple share be stopped? No. All the trend data and research evidence shows the growth of the supermarkets is due to all kinds of social and commercial factors which are outside the control of any single part of the supply chain to influence. Only massive and decisive government intervention can have a material effect.

Can retail multiple power be managed? Yes. There is more and more anecdotal evidence that smart suppliers are able to manage the supermarket relationship much more effectively and proactively than had been feared in the past. The Bain study of WalMart, summarised on the next page, provides some useful pointers.

Page 19

2.10 The Bain study of Wal-Mart

A study of 38 US companies was recently made by management consultancy, Bain & Co. All 38 companies are suppliers of the Wal-

Mart retail group in the USA and have a high exposure to the retailer. The general trend is that as a supplier’s exposure to

WalMart grows, its profit margins decline. Where Walmart’s share of a supplier’s business is under 10%, profit margins average

12.7%. At the other extreme, when Walmart’s share grows beyond

25%, profit margins average only 7.3%.

Yet 9 companies out of the 38 reviewed have managed to maintain their profit levels as the Wal-Mart share has grown. They have done this via three routes which Bain identified as key issues:

•

They made an above-industry-average investment in research to understand the value of their products to the consumer. How does packaging, product quality and image translate into brand values? What is the consumer prepared to pay for that brand? It was only with a detailed understanding of the consumer that they were able to have a more balanced and logical debate with Wal-Mart about consumer pricing and to maintain premium prices on premium brands. They were also able to repackage some products more cheaply where low prices were clearly a bigger issue for the shopper.

•

They invested in understanding the value of their brand to

Wal-Mart. This included analysing the retailer’s own costs in order to assess Wal-Mart’s own return on investment. Yet it also extended to researching how their products built consumer traffic and encouraged additional purchases instore. This data gathering went beyond their own brands to the role of their whole category in the shopper’s “WalMart experience”.

Wessenden Marketing

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

•

They copied Wal-Mart in relentlessly and aggressively pushing down their own costs and in improving supply chain performance, trying to keep business processes as simple and streamlined as possible.

None of this is a revelation, but it does prove that suppliers can partner the major retailers on a more even footing if they are smart and focused. They have done so by taking apart their own businesses with the same rigour as WalMart has done. They have also done all this by engaging fully with Wal-Mart and giving the retailer much more transparency to their own costs and processes.

What other studies of WalMart have shown (e.g Michael Bergdahl:

“What I leaned from Sam Walton: How to compete and Thrive in a

WalMart World”) is that the retailer has succeeded not through radical or innovative strategy, but from a relentless emphasis on cost-control and execution, based on an obsession with continuous learning and continuous improvement. The WalMart mantra is:

•

“Take care of your people….” Managers are required to respond to any staff requests for help, even if it means delaying their own work. When looking to fill staff vacancies, managers two levels above the open position are required to approve all new hirings to ensure that executives do not shy away from hiring subordinates who might outshine them.

•

“Your people will take care of the customer….” The WalMart

Cheer starts every day and ends with the question “Who is number one?” The staff response is “The customer…ALWAYS!” Shop staff, or “associates” in

WalMartspeak, are empowered to make significant refunds on the spot to resolve customer complaints. Managers spend more time in the field than at head office, communicating the message down to the branches, but also obtaining firsthand market intelligence. Under the Ten Foot Rule, associates are required to help, or at least to smile at, customers if they come within a ten foot radius.

Page 20

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

•

“….and the business will take care of itself.” Yet this conceals the obsession with detail and control, not only over WalMart’s own processes, but over those of its suppliers and partners.

As an illustration of both this attention to detail and of its ruthlessness, WalMart USA’s pay week runs from Thursday to

Wednesday, so that any necessary staff cuts are made on the slowest sales days.

To ignore or resist the supermarkets are simply not long-term options. Yet engaging with them should only be undertaken after a realistic assessment of each party’s strengths in the whole supply process.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 21

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

2.11 Conclusions

All this demonstrates a number of issues.

Firstly , the relationship between the publisher and the supermarket is becoming an increasingly complex one. Not only is the retailer’s buying decision as to which magazines to handle complicated by issues of taste and decency, but the magazine publisher is increasingly competing with the supermarket for the consumer’s time & money and for advertisers’ marketing budgets.

Secondly , this role complexity is being driven by the supermarkets’ obsessive and relentless pursuit of the consumer: to understand them; to influence them: to own them. In Tesco’s phrase “to earn their lifetime loyalty.” For products which truly are brands when they understand their consumers intimately and emotionally, magazines have to keep one step ahead of the supermarkets in their consumer insight and in the range of their “consumer touchpoints”.

This is reflected in Tesco’s Mission Statement: “Our core purpose is to create value for customers to earn their lifetime loyalty. We deliver this through our values: (1) non one tries harder for our customers and (2) we treat other people how we like to be treated.”

Thirdly , their attention to detail and processes means that the supermarkets inevitably set the commercial agenda of all the supply chains they deal with, taking apart other people’s business models and reassembling them in more efficient ways. Magazine publishers must understand and streamline their own businesses with the same rigour and also understand the retail model and concerns.

Fourthly , the supermarkets’ influence with the shopper is allowing them to set the consumer agenda, and much of that centres on price. Magazine publishers must have a clear and long-term pricing strategy for all their routes to market: retail, subscription and online.

Fifthly, there is a real conflict of cultures between retailers and publishers. This can be the source of a great deal of misunderstanding and irritation on both sides. It can also be the basis of creative co-working.

All this can result in both exciting new partnerships between publishers and retailers and also in simple competition and role confusion. Yet publishers need to be working closely with supermarkets and understanding their thinking in order to stand a chance of getting a positive result.

All of these issues are explored in more detail in the rest of this report.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 22

Section 3

ON THE SHELF

Supermarkets selling magazines

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

3.1 Supermarket magazine trends

3.2 Supermarket magazine range

3.3 Supermarket magazine profiles

3.4 Why supermarkets handle magazines

3.5 Overview of the interfaces

3.6 The Consumer Interface

3.7 The Shopper Interface

3.8 The Point of Purchase Interface

3.9 The Business Interface

3.10 Assessing supply chain assets

3.11 The MPA Retailing Growth Initiative

Wessenden Marketing

Page 23

Magazines being sold in supermarkets (the “on-shelf” area covered by this report) remains at the core of whole supermarket debate.

The supermarkets are often characterised as very restricted range retailers, creaming off only the very largest titles, constantly reducing range and, therefore, restricting and, indeed, threatening magazine diversity.

They are also seen to be putting retail competitors out of business, wanting to throw the supply chain into chaos to meet their own ends and threatening to rip margin out of its suppliers.

As always, the truth is a little more complex than that, as this section attempts to demonstrate.

Wessenden Marketing

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

3.1 Supermarket Trends

The early tests

The early 1980s saw the first tests of selling magazines in supermarkets, amid much opposition from both wholesalers and traditional retailers.

The initial trials involved less than 10 titles, all of them women’s magazines, which were sold exclusively at the checkouts. It was assumed that UK supermarkets would follow the US model where the checkouts currently account for 56% of total supermarket magazine sales as opposed to 44% for the “mainline” magazine racking in-store. It was also assumed that it would only be women’s magazines which could ever be sold in supermarkets in any volume.

However, events quickly moved on in the UK through the 1980s:

•

Supermarkets developed in-store browser areas and have blown hot and cold over till displays of magazines since then.

•

Supermarkets began to handle a much wider range of magazine titles than had originally been anticipated. This was due in part to the relative importance of the “mainline” display, but also because many supermarkets underestimated what the entry-level point was in offering a range which was big enough to be taken seriously by the consumer. The entrylevel at the very smallest supermarket outlets is currently 40-

50 magazines.

•

Male interest titles have also become significant supermarket sellers.

•

Changes in the magazine market itself with a proliferation of new titles and the renaissance of the weekly magazine have changed some of the supply-side drivers.

Page 24

Growth trends

By 1990, the major supermarkets held a 5% share of consumer magazine industry RSV. Since then, the major supermarkets groups have quickly established a massive presence in the magazine supply chain.

•

The supermarket format currently accounts for 27% of the retail sales value (RSV) of all consumer magazines.

•

The supermarket operators currently account for approximately 30% of the RSV of all consumer magazines

(the “operators” figure is higher as it includes smaller convenience stores run by the major supermarket chains).

In terms of the number of outlets, the supermarket sector still continues to grow.

Number of Outlets Handling News & Magazines

Year

1992

2000

2004

Supermarkets

1,334

3,751

4,407

%

Change

181%

17%

Total

Press

Outlets

44,474

54,621

53,807

%

Change

23%

-1%

Source: ANMW

Between 1992 and 2000, the period when the press retailing universe grew strongly after deregulation, supermarkets were the fastest growing retail sector. Since then, the press retailing universe has leveled out and shown slight contraction, while the supermarket sector has continued to grow.

Wessenden Marketing

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

So, how far will supermarket share go? The chart below shows the current share of category sold through the grocery multiples.

Product

Detergents

Meats

Bread

Milk

Chocolate

Tobacco

Magazines

Chewing gum

Newspapers

Grocers'

Share

90%

80%

70%

65%

40%

35%

30%

30%

10%

Source: AC Nielsen & Wessenden

There are some major differences between press products and other FMCG categories which will restrict the growth of the grocers’ share of the magazine business. The first is that much of the grocers’ growth has been driven by own-label products, which are limited in the press market. The second is that magazines remain an impulse, add-on purchase in supermarkets: continued availability in other outlets will ensure a relatively broad retail spread.

Wessenden’s own estimates for the ceiling of grocery share are:

Product

Magazines

National Papers

Regional Papers

Source: Wessenden

Grocers'

Share

Current

30%

10%

9%

Grocers'

Share

Ceiling

40%

20%

18%

Page 25

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

Magazine Shares by Named Multiple

Retail shares are extremely volatile, but the table below provides a picture of the relative positions of the major players, showing those retailers with a share of over 1%, rounding to the nearest 0.5%.

The supermarket chains (shaded) account for six of the top nine magazine accounts: with Morrisons acquiring Safeways, this in now reduced to five.

Retailer % Share of Total Mag Market

RSV 2004

Retailer

Tesco

WHS High St

WHS Travel

Sainsbury

2004

13

11

7

5.5

Asda

TM

Safeway

Morrisons

4.5

3.5

3

2

Waitrose

Other Multiples

Independents

TOTAL

(Source: Newstrade data)

1

16.5

33

100

Trend

Up

Down

Up

Steady

Up

Steady

Down

Up

Up

Up

Down

Supermarkets have made their biggest impact in the high volume, high frequency sectors of magazine publishing which fit in with the regular pulse of food shopping. Most mainstream weeklies are now heavily dependent on the grocery channel. Weeklies are also easier to handle from a supermarket’s point of view with shelf replenishment being much more straightforward.

The current buoyancy in the weekly magazine market is helping to accelerate the grocers’ share growth .

Wessenden Marketing

Page 26

3.2 Supermarket Magazine Range

The issue of magazine range is highly emotive. There is a common view that supermarkets operate very restricted magazine ranges which are being reduced and are being managed much more rigidly with hard ranging and a strict one-in-one-out policy on new launches. All this is felt to be strangling magazine sales opportunities, especially for specialist consumer and business titles.

Yet magazine range is highly complex and surprisingly difficult to pin down definitively. This is for a number of reasons:

•

Historically, retail head offices have allowed local shop management considerable freedom to make their own local buying decisions. This is changing with the move to hard ranging which has been driven by the supermarkets, but which is being widely adopted by other retail groups. Yet the balance between “mandatory” and “optional” titles varies widely from retailer to retailer, as do the systems to police range effectively.

•

In practice, whatever the retail head offices decided on range was not always implemented locally. With wholesale systems, in the past, unable to lock ranges definitively, the number of titles always grew, driven by the pressure of new launches and constant promotions, which meant that unauthorised titles would creep on to the shelf. Many retailer range reviews are simply about pruning back this “range creep”, rather than a fundamental range reduction.

•

The constantly changing shop portfolios of the major retailers always causes definition problems.

•

Many major retailers are currently going through major regrading programmes of their shop estates.

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

•

From time to time, retailers can shift their strategy for magazines, depending sometimes on the individual supermarket buyer and the importance given to the category in the overall plans of the retailer.

The chart below takes the current high and low points of range for the major supermarkets, showing the average number of titles handled by the smallest outlet up to the every largest (excluding the convenience stores and petrol forecourts in the estate).

Magazine Range Spectrum for the Major Supermarkets (excl. convenience stores)

120 560 Tesco

Morrisons

Sainsbury

Asda

Waitrose

40

45

45

90

250

345

365

440

Limited Range

Under 200 titles

Mid Range

200-400 titles

Extended Range

400+ titles

Source: Wholesaler & distributor targeting systems

To place this in context, WHSmith High Street’s spectrum spreads from 300 up to 1,300 mandatory titles with a list of optional titles to be chosen at the local shop’s discretion in addition. Few outlets come close to WHSmith’s range, but TM Retail has just reranged its

“variety” outlets so that the very largest shops can take almost

1,000 mandatory titles.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 27

The independent retail sector

No. of Titles

Less than 100

100-250

251-400

401-550

551-700

701-1000

More than 1000

TOTAL

% of

Shops

21%

42%

16%

8%

5%

4%

3%

100%

Source: Brandlab

The proportion of independent retailers which can actually be counted as true “range retailers” for magazines is in the minority.

The oft-quoted past when a healthy independent retail sector supported a thriving specialist magazine market is simply not a fact.

Piecing everything together would suggest the following conclusions :

•

The current picture of the supermarkets is that many of their outlets offer significant magazine ranges. They occupy the middle ground between WHSmith and the convenience stores.

Wessenden Marketing

Number of Mags Stocked by Independent Retailers

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

offers a massive spread of magazine range as PPA/Brandlab’s “Magazine & the Independent

Retailer” research project shows. Yet the core of the independent sector is in the limited range 100-250 title band. The weighted average across the whole sample is 283 titles per outlet.

•

Despite periodic pruning back and occasional shifts in strategy, the long-term trend in supermarket ranges has generally been up.

•

However, there is broad tendency to “declutter” the smaller stores and to let only the larger ones offer a real range.

•

Conversion from a CTN to a convenience store or from a broad-based c-store to a grocery-owned one will usually mean a range reduction.

•

The supermarkets have developed their own distinct profile of magazines which is shown in more detail on the next page

(Section 3.3: Supermarket Magazine Profiles”).

The major supermarkets have actually become more committed range retailers of magazines than many “traditional” magazine sellers. This, of course, has its own dangers should the grocers decide to cut back on their magazine space and range in the future.

The most profound impact that the supermarkets have had has been on WHSmith High Street as the grocers have progressively ripped share out of WHSmith in some of its core, high volume magazine sectors, as the chart on the next page demonstrates.

The retail future of specialist and business magazines is much more dependent on the direction and stability of WHSmith than on the supermarkets’ own range policies.

As a footnote on range, as later sections demonstrate, the consumer has a very pragmatic view of the supermarkets’ magazine offer. They know that the grocers’ magazine range is not as wide as that of WHSmith, but they do not expect it to be (in fact, consumers tend to underestimate the size of the magazine range in supermarkets). That is one of the reasons why they have a repertoire of shops to satisfy their total magazine purchasing needs.

The supermarket is just one option, but a very important one, in the consumer’s range of magazine shopping locations.

Page 28

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

3.3 Supermarket Magazine Profiles

45%

40%

35%

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

0%

Grocers vs WHS High St Relative Shares by Mag Sector

TV Listings

Children's

Comics

Women's Interests

Adult

Teenage

5%

WHS Average = 11%

Puzzles

Men's Lifestyle

Motoring

Buying & Selling

10%

Country

Current Affairs

15%

Home Interest Computing

B2B

Sport

Foreign

20%

WHSmith High St

Music

General Interest

25% 30%

Grocer Average = 27%

Leisure

35% 40%

The chart highlights which magazine sectors the supermarkets have made their own, led by

TV Listings titles where over 40% of sales go through the grocery channel. Women’s and

Children’s titles are obvious supermarket sectors; as are weeklies in general, due to the regular pulse of food shopping. While many supermarket magazine sales are impulse buys, there is also a surprisingly large core very committed and regular purchasing. WHSmith

Retail has had to respond to the supermarket incursion into these areas with an increased commitment to range and to lower volume and more specialist sectors.

The chart graphs the percentage of Retail Sales

Value (RSV) which is accounted for by the major grocers (vertical axis) as opposed to WHSmith High

Street (horizontal axis).

The top left area shows those magazine sectors where WHSmith is weak and the supermarkets strong, with TV Listings and

Women’s Interest being the two largest segments.

The bottom right area is made up of WHS strong / grocers weak sectors, which tend to be more specialist magazines.

The bottom left area is made up of magazine sectors which have a more even and traditional balance with independent retailers accounting for a much higher share of the magazine sectors which fall in this quadrant.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 29

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

3.4 Why Supermarkets Handle Magazines

What supermarkets like about magazines

As has been already noted, news and magazines have become an important element in the supermarkets’ non-food offer for the following reasons:

Magazines have provided good growth in retail sales value (RSV).

Magazines, and particularly weekly magazines, provide high levels of repeat buying which helps to build frequency of purchase in the supermarket.

Yet there is also a significant element of impulse buying which helps to build basket size.

Topical editorial and the strong emotional link between reader and magazine mean that the product has a strong image in the consumer’s mind, yet is relatively low priced, resulting in a good perception of value-for-money which is very much part of the supermarket consumer offer.

The ability to create tailored promotions can further build consumer loyalty to a particular retailer.

The synergy with other home entertainment products creates a larger leisure-orientated category which is central to the non-food offer.

Magazines are attractive products in their own right which create a pleasing display at the front of the store and which can extend the length of the shopping trip through browsing, through creating a more relaxed atmosphere for the whole shopping trip, sometimes by linking into the coffee shop area.

Wessenden Marketing

Magazine ranges can be flexed in a very versatile way to suit the space and layout of individual stores.

It is sometimes claimed that magazines are a useful builder of consumer traffic in-store. Yet all the research evidence points to this NOT being the case in the sense that magazines are not the prime motivation for making a shopping trip to a particular supermarket. This is the opposite for outlets such as WHSmith which is a real destination shop for magazines.

What supermarkets dislike about magazines

Lack of control over buying margin. Due to the complexities of the magazine supply chain, and in particular the existence of a strong wholesale sector which provides a frustrating buffer between retailer and manufacturer, retail margins are not a straightforward publisherretailer negotiation (yet).

Lack of control over price. Price is the supermarkets’ most commonly used and most effective promotional lever. With publishers still effectively setting the retail selling price, this tool is not available to the supermarkets.

Complex ranging. One of the leading supermarket groups recently complained that for a category which accounts for only 1% of total store turnover, magazines had the longest and most complicated range review process of any product group. The magazine market is fragmented, complex and very fast-moving which makes it both attractive to the consumer, but very frustrating to edit from a retailer’s display perspective. Increasingly, retailers have moved from simply looking at having a balanced range of sectors and titles to looking more at the financial return of that range. Often, when it comes to the number of titles, “more is less”, and more money can be made be displaying fewer titles better. The level of launch activity in magazines is another complicating factor.

Page 30

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

Poor supplier compliance. The magazine supply chain is actually very bad (sometimes retailers suspect deliberately) at sticking to range guidelines which have been agreed at head office.

Product complexity. A specialist and perishable product which is not delivered ready for the shelf, whose sales vary from issue to issue, which needs constant shelf-tidying and replenishment and which is fully returnable, but within rigid parameters set by the supplier and which has high levels of waste (and shrink): all these factors add up to a resource-hungry category in terms of shop staff time. Yet as future sections of this report will discuss, there is a real distinction between the complexity of the product itself and the complexity of the processes involved in managing the product.

What supermarkets want from magazines

The supermarkets will continue to grow their share of magazines, stealing sales from across all outlet types, by devoting more space to the category, but only if :

•

There is more targeted and flexible ranging to drive better return on investment.

•

There is more promotional activity in-store with a real focus on driving volume. This means more creative and eyecatching displays, but also more “value” promotions (e.g. 2 for 1s, blanket price cuts, cross-merchandising, etc.)

•

The links in the supply chain work together to drive more operational cost savings. These focus on shrink & waste, instore simplification, sales based replenishment and maintaining agreed availability targets.

In short, the supermarkets need to increase their return on investment from magazine display space in order to justify their

Wessenden Marketing commitment to the category. Their preferred route is to cut costs. If this fails, their fallback is simply to grab a bigger share of cover price via one means or another.

Yet the fact is that supermarkets are wedded to magazines, because their customers want them there.

Page 31

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

3.5 Overview of the Interfaces

In the complex relationship between Publisher, Retailer and

Consumer, there are four key interfaces which need to be managed quite distinctly from each other.

CONSUMER

Shopper

Interface

Consumer

Interface

Point of

Purchase

3. The Point of Purchase

The real “hot-spot” where all three participants in the magazine sale come together. What is the process of how and why consumers buy magazines?

4. The Business Interface

The processes that bring the magazine product to market. Are these different for magazines than they are for other FMCG goods?

Can the magazine processes be improved?

The following pages look at each of these areas in turn……

Business

Interface

RETAILER PUBLISHER

1. The Consumer Interface

The direct, one-to-one relationship that the publisher has with the consumer. How does the consumer behave as a magazine reader?

2. The Shopper Interface

The direct one-to-one relationship that the retailer has with the consumer. Where do magazines fit into the shopper’s thinking and purchasing patterns? By extension, where do magazines fit into the retailer’s consumer offer?

Wessenden Marketing

Page 32

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

3.6 The Consumer Interface

Sections 4.5 to 4.8 outline a number of the trends which are characterising the modern consumer.

Recent projects undertaken by the Henley Centre on behalf of the

PPA underline just how complex the modern consumer actually is and how magazines cut through that complexity with the strong emotional links that they engender with their readers.

How Consumers have Changed

In one of its recent reviews of national consumer trends, the Henley

Centre made the following observations about how UK consumers have changed.

•

Consumers are ambivalent about what they want or need.

The majority feel that they have all the material things that they need, but they are not sure what else they want in addition to make them happy.

•

Consumers’ desires are often intangible and unrealistic.

Hence the “cult of celebrity”, of wanting to live someone else’s life. “Quality”, however that is defined, has become more important. Success is measured by how satisfied and in control of life they are rather than by material possessions.

•

Consumers do not just spend money. They are constantly trading off time against money and time has a monetary value. Information overload, especially from the proliferation of media is a key issue. Cutting clutter is a key aim.

•

Consumer spending is under pressure , partly from a slowing economy, partly because of a growing conflict between “living for today” (high spending and high debt) and

“preparing for the future” (lower spending and more saving).

•

Consumers are harder to categorise as lifestyles and established community & family patterns fragment. Everyone likes to think of themselves as an individual.

•

Consumers are increasingly cynical & distrustful , where UK consumer trust levels for their supermarket are almost twice that of those for the current government. In this environment, traditional advertising messages have much less impact where the “referral economy” and “viral marketing” are taking over.

Consumers are increasingly active, involved, demanding, less forgiving and less trusting.

The Bond between Magazine & Consumer

The Henley Centre “Delivering Engagement” project details how magazines can cut through this confusing consumer marketplace to create a real and intimate bond with the reader. Magazines:

•

Deliver trust , acting both as a friend and advocate. Portable and intimate, they find their way into every part of the home and shape themselves around the personal time of the reader.

Authoritative and reliable, they filter information and provide views and insights.

•

Enable participation and provide a bridge to interaction. By providing guidance on a range of subjects, magazines can prompt activity in a number of areas, including increased use of the internet which appears to be a very complementary medium to the print magazine.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 33

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

•

Offer readers help and support in managing their lives. If consumers are preoccupied with self-improvement then magazines are their natural guides and mentors both at home and at work, providing a mix of inspiration and practical advice.

•

Confer and boost readers’ personal status . The choice of magazine is very personal and is often seen as a statement of the kind of person someone is or wants to be seen to be. It makes them feel special and unique.

•

Provide fun, relaxation and escape in a pressured world.

Leveraging the bond with the consumer

There are four practical outputs from the Henley Centre work.

The first is that the magazine medium has a natural affinity with the internet.

Online can enhance the magazine experience, offer new ways to deliver the editorial to the consumer and already is a proven mechanism for selling subscriptions to the consumer. It could offer more protection from the vagaries of the retail route to market.

The second is that magazines can benefit other companies who are associated with them.

The “halo effect” of trust extends most obviously to companies who advertise in the magazines themselves, but could also be leveraged more with retailers: to enhance the shopping experience, to be used in a more direct way to reward the consumer for shopping at that retailer or to develop more in-store activity through linked cross-category promotions and cross-merchandising.

The third is that magazine purchasing is a very powerful and sensitive way to classify consumers , rather than by broad and standard socio demographic, lifestyle or housing classifications.

Publishers could work more closely with the grocers to profile their shopper base.

Yet the most important fact is that magazines are the ultimate in brands . Inspiring fierce loyalty and an intimate bond while being very volatile and difficult to replicate, they are much more resistant to the supermarket debranding and standardisation process than other consumer goods. They are also a “fun” category to deal with, but only as long as the supply chain processes do not create too much irritation and frustration.

Wessenden Marketing

Page 34

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY

3.7 The Shopper Interface

Where do magazines fit into the shopper’s thinking and purchasing patterns? By extension, where do magazines fit into the retailer’s consumer offer?

The general magazine purchasing context

The general magazine shopping patterns across all magazine outlets are shown in the diagram below.

Magazine Repertoire

Average no. of titles in repertoire

Average no. of issues bought per month

10.7 titles

4.0 issues per month

Channel

Repertoire

I buy mags mainly from retail

I buy mags mainly via subscription

I buy mags via both retail & subs

Total regular magazine buyers

63%

16%

21%

100%

Magazine Shop

Repertoire

Average no. of shops from which magazines are bought on a regular basis

2.9

Magazine Shop

Visits

Average times that a shop selling magazines is visited

Average times that a magazine purchase is made

Average no. of mags bought per purchase occasion

15.2 visits per mth

2.9 purchases per mth

1.3 mags per purchase

Magazine

Shop Visits by Mode

BUYING MODE: I wanted a mag & bought one

BUYING MODE: I wanted a mag & couldn't find it

BROWSING MODE: Just browsing & didn't want to buy

NON-BUYING MODE: I didn't want to buy a magazine this time & just walked past the mag display

Total mag shop visits per month

3 visits per mth

3 visits per mth

4 visits per mth

5 visits per mth

15 visits per mth

MAGAZINE REPERTOIRE: Magazine buyers are selecting their purchases each month from quite an extensive repertoire of titles.

CHANNEL REPERTOIRE: A significant (21% of regular magazine buyers) and increasing proportion is buying regularly via both retail and subscriptions.

MAGAZINE SHOP REPERTOIRE

•

No single shop satisfies the consumer’s demand for magazines.

•

Supermarkets have become the most popular location for buying magazines as the table below demonstrates

Where do you purchase the majority of your magazines from?

Supermarket

High St newsagent

Local independent retailer

Petrol station

Transit point

All magazine buyers

36%

34%

28%

1%

1%

100%

MAGAZINE SHOP VISITS & BUYING MODES: Magazines are very widely available and the consumer passes magazine racks

15 times per month, but only buys on 3 occasions.

•

As magazines are usually bought for immediate consumption, what triggers the purchase is often some available “treat” or leisure time.

•

On 6 of the shop visits, the consumer is in “buying mode”, actively looking to buy. Yet actual magazine purchases are only made on half of those occasions, the main reason being that the desired title is not on-shelf. Magazine purchasing is polarised between (1) very purposeful, title-specific searching when the consumer will visit other outlets in order to obtain the magazine they want and (2) very impulsive buying “on spec”.

•

Browsing is involved on many purchasing occasions as the consumer often checks the repertoire before making a final

Wessenden Marketing

Page 35

MAGAZINES IN A SUPERMARKET ECONOMY buying decision. It is also a pleasurable leisure activity in its own right, particularly among men, and is often undertaken when there is no intention of buying.

Supermarket magazine shopping

Magazine buyers interviewed immediately after a visit to a supermarket (PPA / Brandlab: “Magazines & the Multiple Retailer) showed the following characteristics:

1. Supermarket visits are very frequent

Shoppers visited that particular supermarket 8.7 times per month on average. This regular shopping pulse is commented on in focus group work by both Brandlab and the Magazine Publishers of

America in the USA: it makes the purchase of the core, regular magazines in the consumer’s repertoire very easy and convenient when on the grocery shopping trip and explains why weekly magazines fit so neatly into the supermarket offer.

2. Magazines do not drive the supermarket shopping trip

Supermarkets