Issues and Potential - American Association of Wine Economists

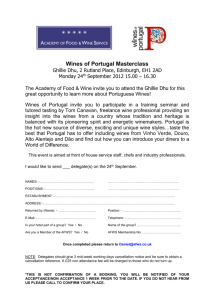

advertisement