Business Law II Notes

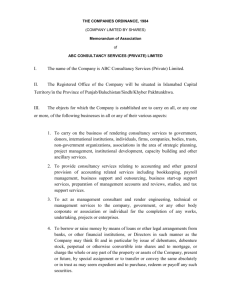

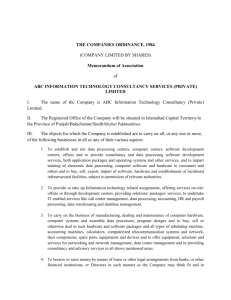

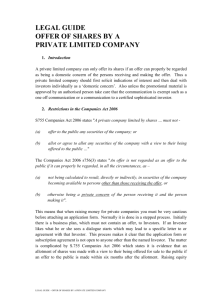

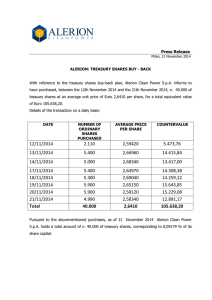

advertisement