Ratification and Undisclosed Principals

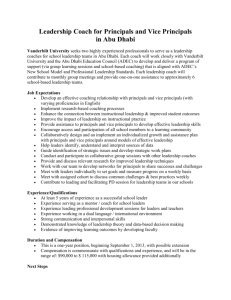

advertisement