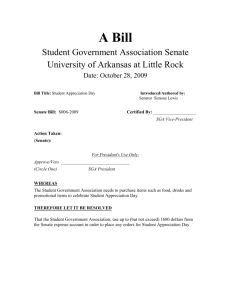

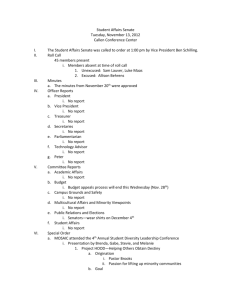

here

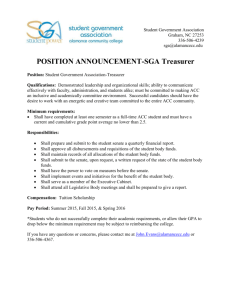

advertisement