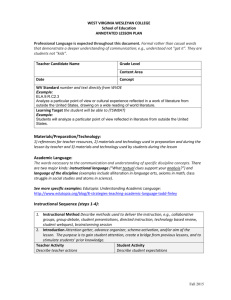

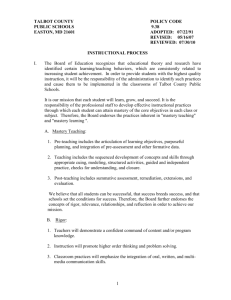

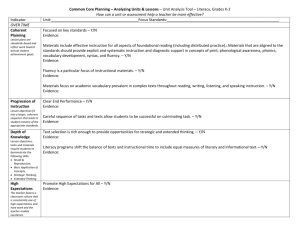

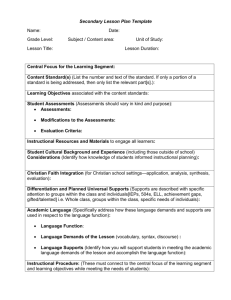

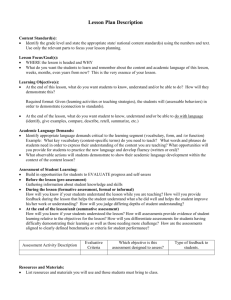

Instructional Planning & Delivery

advertisement