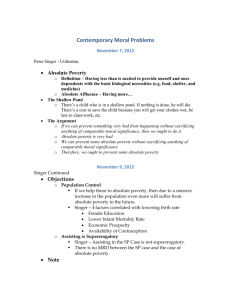

Singer and Unger on the Obligations of the Affluent

advertisement