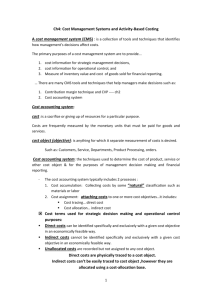

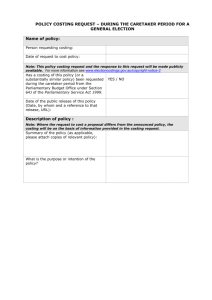

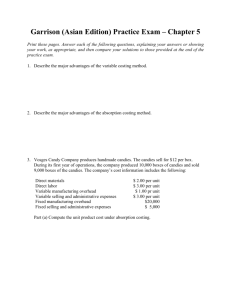

Measuring Cost of Operations

advertisement