Black Laws - Shenandoah County Historical Society

advertisement

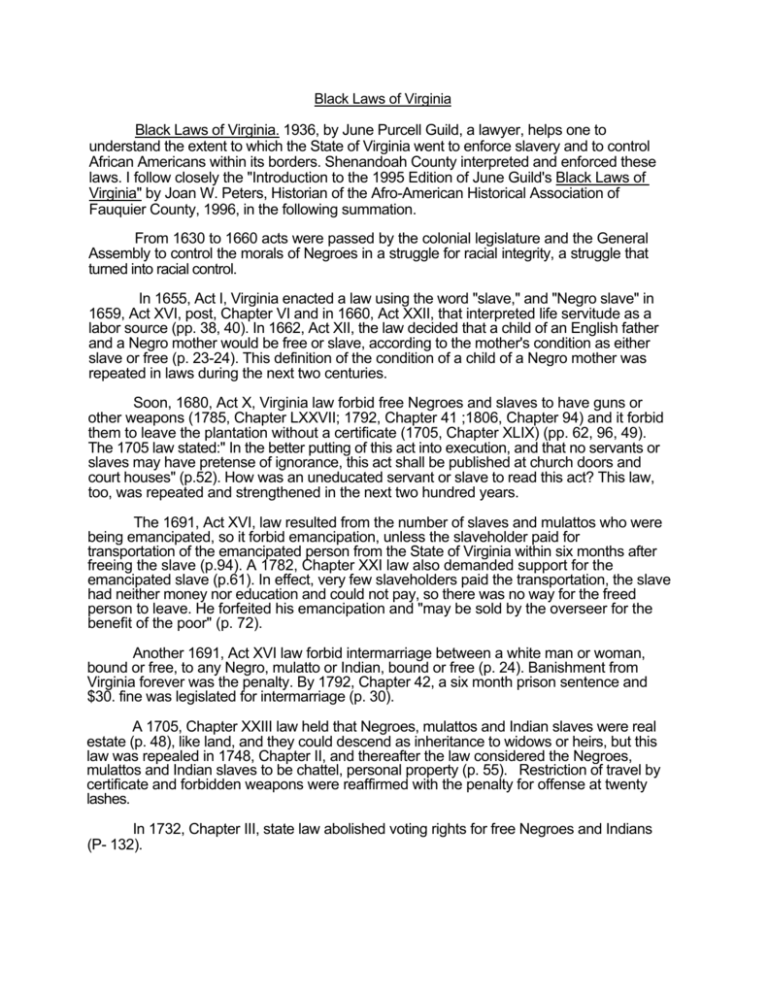

Black Laws of Virginia Black Laws of Virginia. 1936, by June Purcell Guild, a lawyer, helps one to understand the extent to which the State of Virginia went to enforce slavery and to control African Americans within its borders. Shenandoah County interpreted and enforced these laws. I follow closely the "Introduction to the 1995 Edition of June Guild's Black Laws of Virginia" by Joan W. Peters, Historian of the Afro-American Historical Association of Fauquier County, 1996, in the following summation. From 1630 to 1660 acts were passed by the colonial legislature and the General Assembly to control the morals of Negroes in a struggle for racial integrity, a struggle that turned into racial control. In 1655, Act I, Virginia enacted a law using the word "slave," and "Negro slave" in 1659, Act XVI, post, Chapter VI and in 1660, Act XXII, that interpreted life servitude as a labor source (pp. 38, 40). In 1662, Act XII, the law decided that a child of an English father and a Negro mother would be free or slave, according to the mother's condition as either slave or free (p. 23-24). This definition of the condition of a child of a Negro mother was repeated in laws during the next two centuries. Soon, 1680, Act X, Virginia law forbid free Negroes and slaves to have guns or other weapons (1785, Chapter LXXVII; 1792, Chapter 41 ;1806, Chapter 94) and it forbid them to leave the plantation without a certificate (1705, Chapter XLIX) (pp. 62, 96, 49). The 1705 law stated:" In the better putting of this act into execution, and that no servants or slaves may have pretense of ignorance, this act shall be published at church doors and court houses" (p.52). How was an uneducated servant or slave to read this act? This law, too, was repeated and strengthened in the next two hundred years. The 1691, Act XVI, law resulted from the number of slaves and mulattos who were being emancipated, so it forbid emancipation, unless the slaveholder paid for transportation of the emancipated person from the State of Virginia within six months after freeing the slave (p.94). A 1782, Chapter XXI law also demanded support for the emancipated slave (p.61). In effect, very few slaveholders paid the transportation, the slave had neither money nor education and could not pay, so there was no way for the freed person to leave. He forfeited his emancipation and "may be sold by the overseer for the benefit of the poor" (p. 72). Another 1691, Act XVI law forbid intermarriage between a white man or woman, bound or free, to any Negro, mulatto or Indian, bound or free (p. 24). Banishment from Virginia forever was the penalty. By 1792, Chapter 42, a six month prison sentence and $30. fine was legislated for intermarriage (p. 30). A 1705, Chapter XXIII law held that Negroes, mulattos and Indian slaves were real estate (p. 48), like land, and they could descend as inheritance to widows or heirs, but this law was repealed in 1748, Chapter II, and thereafter the law considered the Negroes, mulattos and Indian slaves to be chattel, personal property (p. 55). Restriction of travel by certificate and forbidden weapons were reaffirmed with the penalty for offense at twenty lashes. In 1732, Chapter III, state law abolished voting rights for free Negroes and Indians (P- 132). In 1705,1765 and 1785, penalties increased for women whose illegitimate children were fathered by a Negro or mulatto. At first the parish churchwardens, later the Overseer of the Poor, bound out the illegitimate males until age twenty-one and the females until age eighteen (1765, Chapter XXIV) (p.27). In 1785, Chapter LXXVII legislation again forbid travel without letter or license from the slaveholder, riots, unlawful assembly, or carrying firearms, although Negroes on the frontier could be licensed to carry a gun (pp. 62, 64). In 1878, Chapter 311 penalties for intermarriage between races were increased by jail terms of two to five years in the penitentiary for a white or Negro who intermarried, to replace earlier fines levied upon the parties and the minister (p.34). In 1932, Chapter 78 stated: "if any white person intermarry with a colored person, or any colored person intermarry with a white person, he shall be guilty of a felony and confined in the penitentiary for from one to five years" (p.36). The 1783, Chapter XXXII law attempted to stop Negro slaves from hiring themselves out as free colored, and it held the slave and the owner responsible (p.61). The sheriff may sell and dispose of the slave. Also the 1783, Chapter 22 and 1801, Chapter 70 laws were passed to register all free Negroes and mulattos with the Clerk of the Court in which they lived. The registration, to be kept by the Clerk, included name, age, color, status and details of the emancipation, by whom and where it took place (p.95). Following proof pf emancipation, the county courts were to issue a Certificate of Freedom to the emancipated Negro, the certificate to be kept by the Negro as proof of his or her identity. Re-registration every three years was required of all free Negroes and mulattos. In 1801, Chapter 70 the Commissioner of Revenue was required to submit annually a list of all free Negroes in the County and to post a cppy of the list on the Court House door (p.95). If a free Negro moved to another place without employment, he or she would be jailed as a vagrant. The 1806, Chapter 63 law stated that if a slave, emancipated after May 1, 1806, remained in the Commonwealth for more than a year, his freedom would be forfeited by law and he would be sold by the Overseer of the Poor for the benefit of the parish [Beckford Parish in Shenandoah County] (p. 72). However, by the 1827, Chapter 26 law, the Sheriff, upon authorization by the Circuit Court, became the selling agent for free Negroes who had overstayed the year following their emancipation (p. 103). Then, in 1831, Chapter XXXIX, the Sheriff alone was authorized to sell free Negroes in violation of the one year period, at public auction (p. 106). In 1834, Chapter 68, the Circuit Court only was approved to order the registration of free colored by the Clerk of the Court, and he was to include a description of any scars or marks on the registrant (p.110). Many emancipated Negroes petitioned to remain in Virginia, so the In 1837, Chapter 70, law allowed that they could petition the local Court for permission to remain, and upon proof of good character etc., wjth a two month notice of the petition at the Court House door for the free Negro to remain in Virginia, and agreement of three-fourths of the Justices of the Court, permission could be granted locally for the petitioner to stay in the County (p.111). The General Assembly in 1816, Resolution No.1 requested the Governor to correspond with the President of the United States, to obtain territory upon the coast of Africa or the shore of the North Pacific, to serve as a refuge for free Negroes (p.99). [The American Colonization Society organized in Washington City in 1818.] In 1832, Chapter XXII, the legislature had combined many earlier laws into one that prevented assembling and free speech at religious meetings of free Negroes and slaves, their attendance being upon the approval of the slaveholder (p. 107). An 1832, Chapter XXII law prohibited any free Negro for owning any slave, other than spouse or children, except through inheritance (p. 107), and by 1858, Chapter 47 free Negroes could own slaves only by inheritance (p. 120). After Nat Turner's rebellion had failed, in 1833, Chapter 12, $18,000.00 per year for five years was appropriated by the legislature to encourage the transportation and support of free persons of color who wanted to emigrate to Liberia or the west coast of Africa (p.108). 1850, Chapter 6 apportioned $30,000 for the removal of free persons of color to Africa (p. 139), and 1853, Chapter 55 apportioned $30,000 for five years for the removal of free Negroes from the Commonwealth (p.119). The Virginia law included many entries regarding runaways and a review of them indicates how often and how much the laws changed. 1657. Act CXIII: "Runaways, if found, shall be sent from constable to constable until delivered to their master or mistress" (p. 39). 1658. Act 111: "...the master of every runaway shall cut the hair of ail such runaways close above the ears, whereby they may be with more ease discovered and apprehended" (p. 39). 1663, Act VIII: "Runaway servants are to be pursued at public expense, and letters written to the Dutch (Northern) plantations to make seizure of fugitive servants" (p. 42). 1666. Act IX: "The penalty is increased for harboring runaway servants who serve by their first indenture" (p. 42). 1670. Act I: ",„ the sum of 1,000 pounds of tobacco for a reward for taking up a runaway is reduced to 200 pounds...; and that the servant who has run away twice shall have his hair cut close under a penalty for the master for neglecting this; that every constable into whose hands a fugitive passes, shall whip him severely" (p.44). 1705. Chapter XLIX: "Rewards are to be given for taking up runaway servants or slaves. Such runaways are to be conveyed from constable to constable until carried home and lashed not exceeding thirty-nine times. Damages may be recovered if a constable or sheriff permit a runaway to escape. Runaway servants shall repay all expenses. In case any slave who has run away does not immediately return home after a proclamation at the door of every church in the county, it shall be lawful for any person whatsoever to kill and destroy such slave by any means as may be thought fit without accusation of any crime. If any runaway slave shall be apprehended, it shall be lawful to order such punishment, either by dismembering or any other way not touching his life, as may be thought fit, for reclaiming such incorrigible slave, and terrifying others from like practices" (p. 51). 1726. Chapter IV: "For the encouragement of constables to perform their duty in conducting runaway slaves, they are exempt from the payment of all public, county and parish levies. Runaway slaves, whose masters are not known, may be hired out by the keeper of the public gaol, with a strong iron collar with the letters 'P.G.1 stamped thereupon" (p.53). 1765. Chapter XXV:" ...runaway slaves and servants may be carried by the taker-up to the owner; the taker-up shall be entitled to five shillings for taking up, and four pence for every mile covered" (p.58). 1769. Chapter XIX: "The taker-up of a runaway at his option may convey him to his owner, or if the owner is not in the county, carry him to gaol, and the gaoler shall advertise a description in the Virginia Gazette for three weeks. Whereas many owners of slaves in consideration of wages to be paid by such slaves license them to go at large, to trade as free men, which is a great encouragement to theft and other evil practices by the slaves, in order to enable them to fulfill their agreements with their owners; it is enacted that if any owner license a slave to trade as a free man, he shall forfeit the sum of ten pounds in current money for the use of the poor of the parish, to be recovered by the church wardens" (pp. 58-59). 1785. Chapter LXXXIV: "Runaway servants and slaves may be apprehended by any person, who shall be rewarded by the owner. If the owner is not found, the runaway shall be placed in jail, and may be hired out with an iron collar on his neck. A runaway being a slave, after one year from the last advertisement in the Virginia gazette, shall be sold" (p. 63). 1808. Chapter 15:" Any person who may hereafter apprehend a runaway slave shall be entitled to a reward of $2.00, and milage heretofore. If the owner does not claim a runaway within twelve months, the sheriff shall advertise for one month in any public newspaper the time and place of selling the runaway" (p. 73). 1817. Chapter XXXVI: "...from the frequent elopement of slaves to states north of the Potomac... $20.00 reward, and mileage, be allowed any person who may apprehend any runaway attempting to cross the Potomac if the plantation on which the slave is employed be not less than ten miles from the river. If the slave is apprehended in Maryland or Kentucky, the reward shall be $25.00; in Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, or Ohio, $50.00, plus twenty-five cents a mile. Keepers of bridges and ferries must not permit slaves to cross the river without special permits. Runaway slaves committed to jail shall be advertised in a Richmond newspaper" (pp. 77-78). 1822. Chapter 22: "Runaway slaves confined to jail hereafter are not to be sold by the sheriff, except on court order" (p. 81). 1823. Chapter 30: "Whenever a runaway slave is confined in jail and is not provided with adequate clothing, is shall be the duty of the jailor to furnish him with proper Negro clothing or other necessities" (p.81). 1824. Chapter 36:... jailers are to report to courts confined runaway slaves within two months. ... if the court be of the opinion that the runaway will not sell at auction for sufficient to pay the prison fees after being confined twelve months, they shall fix the time of imprisonment for a shorter period and order the slave sold" (p. 83). 1835. Chapter 62: "If the owner of a runaway slave does not claim him within four months after the keeper of the jail has advertised, the slave shall be sold" (p.84). 1841. Chapter 73: "Any person apprehending a runaway slave above sixteen years of age more than twenty miles from his place of abode and within ten miles of dividing lines between Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Maryland shall be entitled to recover $30.00 and ten cents for every mile he shall necessarily convey the runaway" (p. 86). 1856. Chapter 49: "...increasing the reward for the arrest of runaway slaves...(p.90). 1866. Chapter 17:" This act repeals all acts and parts of acts relating to slaves and slavery"(p. 93). As one reviews these Black Laws, one notices that many were established by 1785 and were repeated and expanded as tougher and tougher violent penalties were established from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. To be sure, many laws were enacted on other subjects regarding Negroes: patrols, taxes, hiring out, unlawful assembly, conspiracy, insurrection, and fugitives. Post Civil War laws established separate but "equal" registration of voters, separate railroad coaches, separate steamboat and bus spaces, separate entertainment seating. 1928 voting registration and payment of $1.50 poll tax per resident became prerequisites for voting. The application to register, quite tricky for one who may have had difficulty reading or writing, had to be in one's own handwriting without aid, stating name, age, occupation "and so on. Also the applicant must answer any other question affecting his qualifications as an elector" (p. 149). Thus, again, were many African American Virginians silenced and prohibited from voting. The Black Laws bring us official facts from the past to indicate what happened to African Americans in Shenandoah County. Finding how these laws were interpreted and enforced in Shenandoah County are part of this quest. Nancy B. Stewart August 6, 2007