Party Polarization and Legislative Gridlock - Baruch College

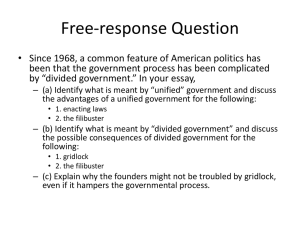

advertisement

_s Party Polarization and Legislative Gridlock DAVID R. JONES, BARUCH CITYUNIVERSITY OFNEWYORK COLLEGE, This articleinvestigates how partiesaffectlegislativegridlock-the inabilityof governmentto enact significantproposalson the policy accountssuggestthatdividedpartycontrolof govagenda.Conventional ernmentcausessuch stalemate.I offeran alternative partisanmodelof gridlockthatincorporates partypolarization, partyseatdivision,andthe interaction betweenthesetwofactors.Usingan originaldataset of major legislativeproposalsconsideredbetween1975 and 1994, I find that and dividedgovernment doesnot affectgridlockoncepartypolarization partyseatdivisionaretakenintoaccount.Instead,I findthathigherparty increasesthelikelihoodof encountering gridlockon a given polarization to theextent but that the of this increase diminishes proposal, magnitude andvetoes. thata partyis closeto havingenoughseatsto thwartfilibusters The persistence of divided party control of the legislative and executive branches of governmentover most of the last three decades has prompted an extensive,and as yet unresolved,debateabout whetheror not this phenomenon leads to the stalematein the lawmakingprocesswhich is often referredto as gridlock. In the meantime,however,anotherphenomenon has been takingplace in Americanpolitics that has receivedscant attentionin studies of legislativegridlock: the policy preferencesof the two partieshave become increasinglypolarized. Since 1990, more than half of all congressionalvotes have featureda majority of one party opposing a majority of the other party. This level of party polarizationrepresentsa steadyincreaseover the 47 percentof such votes in the 1980s and 39 percentin the 1970s. To date, despite the indisputablerise in party polarization,few scholarshave included a thoroughinvestigationof partypolarization in their studies of gridlock. This articleexpands our understandingof legislativegridlockby examining how partypolarization,in conjunctionwith varyingpartisanseat arrangements, NOTE: The authoris gratefulto KathleenBawn,SarahBinder,MonikaMcDermott,BarbaraSinclair, GeorgeTsebelis,anonymousreviewers,and the editorsof PoliticalResearchQuarterlyfortheir commentson earlierversions of this article. Vol. 54, No. 1 (March2001) pp. 125-141 PoliticalResearchQuarterly, 125 PoliticalResearch Quarterly affectsthe relativeinabilityof governmentto enact significantproposalson the policy agenda. First, I briefly review the literatureon the divided government hypothesisand discuss some aspectsof the theory that might explain the mixed empiricalfindings.I then offeran alternativetheoryto explainhow partiesaffect gridlock.This new theory focuses on partypolarization,and its interactionwith partyseatdivision.I test these two hypotheses,using an originaldataset of major legislativeproposalsconsideredbetween 1975 and 1998. The resultssuggestthat partiesdo affectgridlock,but that their impact is more complex than the standarddivided governmentargumentsuggests. GRIDLOCK PARTISANMODELSOF LEGISLATIVE The standardpartisanmodel thathas been offeredas an explanationfor legislative gridlock (or its counterpart,productivity)is the divided government hypothesis (see Sundquist 1988; Cutler 1988; Kelly 1993; Cameron,Howell, Adler,and Riemann1997; Edwards,Barrett,and Peake 1997). The divided governmenthypothesis claims that legislationis less likely to be enacted when the President'spartydoes not hold a majorityof seats in both chambersof Congress. Supportersof this hypothesisexplainthat the constitutionalseparationof powers requirespolicy agreementamong the House, Senate,and Presidentin order for bills to become law.They furtherarguethat agreementamong these threebodies is likely to be thwartedduringdivided government(see also Kernell1991). While the divided governmentargumentis quite intuitive, empiricalsupport has been mixed. For example,while Mayhew's(1991) systematicanalysisof significantlaws passed in the postwar era finds no evidence that divided government is any less productivethan unified government,Kelly (1993) reexamines Mayhew'sdata using differentcriteriafor "significantlaws"and finds that divided governmentdoes reduce enactmentof these laws. Takinginto account the non-stationarynatureof time series data, Cameron,Howell, Adler,and Riemann (1997) find that divided governmentreduces enactment of "landmark" legislation,but increasesenactmentof less significantlegislation.Edwards,Barrett, and Peake (1997) find that divided governmentincreasesfailureof legislation opposed by the President,but does not increasefailureof legislationthat the Presidentsupports. Binder (1999) finds that divided government produces a mild increasethe proportionof salient legislationthat fails, but has an effect no greaterthan severalother causalvariables. It is possible to explain the mixed empiricalevidence regardingthe legislative effect of divided governmentby re-examiningthree implicit assumptions made in the divided governmentargument.First,the divided governmentargument implicitlyassumes that passagein Congressrequiressupport from only a simple majorityin both chambers.Second, the argumentimplicitlyassumesthat Congressand the Presidentmust agree in order to break gridlock. Third, the argumentimplicitlyassumes that the two majorpartieshave distinctlydifferent 126 andLegislative Gridlock PartyPolarization policy preferences.I shall illustratehow violationsof these assumptionscan lead to breakdownsin the divided governmenthypothesis. The argumentthatunifiedgovernmentis not prone to gridlockassumesthat passagein Congressrequiressupportfromonly a simple majorityin both chambers. If this were true, then unified governmentwould guaranteethat the President'sparty had enough seats in Congressto pass its legislativeagenda. In the Senate,however,a minorityof memberscan preventfinal action on a bill by filibustering(or credibly threateningto do so), and thereby prevent enactment. Endinga filibusterrequiresthe supportof three-fifthsof the Senate,or 60 out of 100 votes. Therefore,unifiedgovernmentin which the Presidenthas the support of less than three-fifthsof the Senatecould be just as proneto gridlockas divided government. Furthermore,the prediction that divided government leads to gridlock assumes that Congressand the Presidentmust agreein orderto breakgridlock. If this were true, then presidentialoppositionto legislationpassedby the majority party in Congress would prevent enactment during divided government. However, the presidentialveto power is not absolute. Congress can override presidentialvetoes with a two-thirdsvote in both chambers.Therefore,whenever two-thirdsof the House and Senatesupport a bill, divided governmentwill not necessarilylead to gridlock. The prediction that divided government causes gridlock also implicitly assumesthat the two majorpartieshave distinctlydifferentpolicy preferences.In this article I use the term "partypolarization"to describe the degree to which party preferencesare distinct from each other.1When party preferencesare highly polarized,membersof one partyare more likely to be uniformlyopposed by membersof the otherpartyon the policy matterat hand. Since the President's partylacks a majorityin Congressduringdivided government,highly polarized partieswould mean thatlegislationsupportedby the Presidentwould be unlikely to musterthe majorityneeded to pass in Congress,and legislationthat passed in Congresswould likely be opposed by the President,thus promptinga veto. However,just because governmentis divided it does not necessarilyfollow thatthe respectivepreferencesof the two partiesareclearlydistinct.In the American system of government,party preferencescan be highly polarizedin some cases and have a considerabledegreeof overlapin other cases. When partypreferences are significantlyless polarized, members of one party may be no less likely to vote for a measurethan membersof the other party are. In this case, divided governmentwill not necessarilypreventagreementbetween the legislative and executivebranches. 1 In other words, polarizedpartiesare partieswhose respectivepolicy views would be distantfrom each other if placed on an ideologicalscale. I do not seek to identify the particularsource(s) of partypolarization,I am merelyinterestedin its effectson gridlock. 127 PoliticalResearch Quarterly Overall, the argumentthat divided party control of governmentleads to gridlockis premisedon assumptionsof majorityrule, absoluteveto, and distinct parties.By takinginto accountthe importanceof the filibuster,veto override,and variationin partypolarization,I shall attemptto constructan improvedmodel of how partiesaffectlegislativegridlock. The divided governmentargumentassumesthat supportfromthe President and a simple majorityin the House and Senateare necessaryand sufficientconditions for enactinga law.As a result of the filibuster,however,legislationsupportedby the Presidentneeds not only simple majoritysupportin the House, but also three-fifthssupport in the Senateto overcomegridlock.As a result of veto overrideprovisions,legislationopposed by the Presidentcan, in fact, overcome gridlockif it has two-thirdssupportin the Senateand in the House. Overall,in orderforlegislationto overcomegridlockthe Senatealwaysneeds to have at least three-fifthssupport and sometimes as much as two-thirds, while the House alwaysneeds to have simple majoritysupport, and sometimes as much as twothirds. Recent works by Jones (1995) Krehbiel(1998) and Bradyand Volden models focusing on the (1998) formalizethis argumentthat supermajoritarian Senatefilibusterand the veto are more appropriateto the study of gridlockthan majoritarianmodels (such as the divided government hypothesis). However, institutionsare generally these gridlockmodels that focus on supermajoritarian have to and thus little (or test) models, say regardinghow various nonpartisan more or make less likely (other than of conditions gridlock types partisan might to suggest that divided governmentis irrelevant). Given that not only majoritysupport, but often supermajoritysupport is needed to breakgridlock,what partyvariablesaffectthe likelihoodof achieving largemajoritiesin eachchamber?One factoris the levelof partypolarizationin each chamber.When partypolarizationis low, Democratsarenot uniformlyopposedto Republicanproposals,and Republicansare not uniformlyopposed to Democratic proposals.Withthe possibilityof votes fromboth parties,largermajoritiesaremore likely,and thereforegridlockshouldbe less likely(see also Binder1999). At the same time, however,while low partypolarizationshould reduce the likelihood of gridlock,higher partypolarizationmay not uniformlyincreasethe likelihood of gridlock. Instead, the effect of higher party polarizationmay be dependenton a second partyvariablein each chamber:partyseat division.In the Senate, when neither party is close to having a filibuster-proofor veto-proof majorityhighly polarizedpartiesshould be most likely to cause gridlock.This is because neitherpartyhas enough seats to preventa filibusteror overridea veto if the otherpartysolidly opposes its agenda,and partypolarizationincreasesthe oppositionof one party'smembershipto the otherparty'smembership.2However, 2 Any group of 41 or more like-mindedSenatorscan filibuster.In this sense, low partypolarization is no guaranteeof relief from the threat of filibusters.On the other hand, however, high party 128 andLegislative Gridlock PartyPolarization as a party comes closer and closer to a filibuster-proofand veto-proofmajority (such as a three-fifthsmajorityalongwith controlof the Presidency),partypolarization should become less and less likely to increase gridlock. This happens because as a partygets closer to the supermajorityof seats it needs to enact its agenda,it needs fewervotes frommembersof the other party.Therefore,higher party polarizationis less of an obstacle to the supermajoritysupport that is needed to breakgridlock. In other words, as a partygets closer to a veto-proof and filibuster-proofmajorityin the Senate,partypolarizationprovidesa diminishing marginalboost to legislativeobstruction. Partyseat division should have a similareffectin the House. When the President'spartydoes not have a majorityand the opposition partydoes not have a veto-proofmajority,highly polarizedpartiesshould be most likely to cause gridlock. This is because neitherpartyhas enough seats to enact its agendawithout help from the other party However,as the President'spartyapproachesmajority partystatusin the House (or, less likely,the opposition partyapproachesa vetoproofmajority)partypolarizationshould become less likely to increasegridlock. In these cases, a partyneeds less help fromacrossthe aisle to pass its agenda.In sum, as a partyapproachesthe majorityit needs to pass its agendain the House without fearof a veto, partypolarizationprovidesa diminishingmarginalboost to legislativeobstruction. Overall,reanalyzingthe assumptionsof the divided governmenthypothesis suggestsa new, more nuancedhypothesisregardingthe effect of partieson gridlock. This new hypothesis,which I will referto as the partypolarizationhypothesis, arguesthat unified versus divided governmentper se does not affectgridlock. Instead, gridlock is caused by the interaction between two partisan variables:party polarizationand party seat division. While a few scholarshave looked at one or the other of these variables,none has analyzedthe interaction between them that is central to this hypothesis. Binder (1999) examines the effect of partypolarizationon gridlock,but does not take into accountvariation in party seat division. She thereforedoes not test whether the effect of party polarizationdiminishesunder certainpartisanseat configurations(as the discussion abovewould suggest).In fact, Bindersuggeststhat divided governmentwill still have an effecton gridlockeven when partypolarizationis takeninto account -an assertionthatis contraryto my hypothesis.Coleman(1999) looks at Senate supermajorities,but only as a dichotomousvariable,and without consideringits interactionwith partypolarization.3 polarization-in which membersof one partyuniformlyoppose membersof the other party-will necessarilyincreasethe threatof filibusterswhen neitherpartyhas a filibuster-proofmajority 3 Coleman does consider possible effects of divisions within each congressionalparty,but not directlybetween parties,and not in interactionwith partyseat division. 129 PoliticalResearch Quarterly In contrastto previousworks, this study arguesthat higher partypolarization increasesgridlock,but that the magnitudeof this increasediminishesto the extentthata partyis close to havingenough seats to thwartfilibustersand vetoes. Therefore,unifiedgovernmentis just as proneto gridlockas dividedgovernment when parties are highly polarizedand neither party has a large majority.Conversely,divided governmentis just as productiveas unified governmentwhen party polarizationis low or when one party has a veto-proof, filibuster-proof majority. DATA AND METHOD This articleexamineshow differentpartisanconfigurationsaffectthe relative inability of government to enact significant proposals on the policy agenda ("gridlock").Given this goal, the first step in the analysis is to identify what Mayhew(1991: 35-36) refersto as the "agendaof potential enactments."Once this agendais identified,it is then possible to comparethe conditionsassociated with governmentalfailurerelativeto those associatedwith governmentalsuccess, for each item on the policy agenda. Kingdon(1984: 3) defines the agendaas "thelist of subjectsor problemsto which governmentalofficials,and people outside governmentclosely associated with those officials,are payingsome serious attentionat any given time."I idenQuarterlyWeekly tify such significantpotential enactmentsusing Congressional lists of majorlegislativeproposalsfor every Congressfrom 1975 through Report's 1998 (94th-105th Congress).The startingdate of 1975 is used becausethis is the firstyear that the three-fifthscloturerule for ending filibusterswent into effect.4 For each Congress, I examined every issue of Congressional QuarterlyWeekly Reportthat was published duringits two-yearterm. Using every periodic list of major legislativeproposals contained in these issues, I compiled one comprehensivelist for each Congress.FollowingMayhew(1991: 40), I exclude fromthis data set a small number of proposalsthat would not constitute "law"if passed, includingpresidentialappointmentsand non-bindingcongressionalresolutions. I also exclude treaties,which do not requirepassagein both chambers. The smallest possible unit of analysisfor gridlock is the failureof a single item on the policy agenda.Specifically,gridlockcan be said to occur whenevera 4 From 1917 until 1975 the Senateoperatedunder a two-thirdscloturerule. With a two-thirdscloture rule, the theorywould predicta slightlydifferentrelationshipbetween partypolarization,seat share and gridlock.For example,with the two-thirdscloture rule (priorto 1975) partypolarization in the Senatewould be expectedto producegridlockeven when a partyheld between 60 and 66 percentof Senateseats. With the currentthree-fifthscloturerule, partypolarizationis not necessarilyexpected to increasegridlock in this seat range. For purposes of brevity and clarity,this work does not attemptto elaborateand test the differentimplicationsof the theoryunder different cloturelevels. 130 andLegislative Gridlock PartyPolarization significantproposal on the policy agenda fails to be enacted into law during a two-yearCongress.Using this definition, I create a dichotomous gridlockvariable. Thisvariableis coded 1 for proposalsin the dataset that failedto be enacted into law-regardless of what stage in the legislativeprocess the proposaldiedand 0 for proposalsthatwere enactedinto law-regardless of the particularroute to enactment.5 For each case in the dependent variable,we need a measurementof party polarizationand a measureof partyseat division in each chamber.Partypolarizationvariesnot only acrossCongresses,but also acrossmajorpolicy initiatives within a given Congress.In the 105th Congress,for example, the partiesheld widely divergentviews from each other on the subject of managedhealth care, but held positions that were more difficultto distinguish from one another on the subject of transportationfunds. This study arguesthat even within a Congress, policies on which the partieshave similarpreferencesshould be less likely to become mired in gridlock than policies on which the partiespreferencesare far apart.Therefore,measuresof partypolarizationthat are aggregatedby Congress are inappropriatefor testing the hypothesisat this level (and can even lead to counterfactualinferences;see King 1997). Since only individual-levelanalysis can effectivelybe used to explain variationsin gridlock across policy items as well as acrossCongresses,I measurepartypolarizationon a case-by-casebasis as the absolutedifferencebetween the percentageof Democratsvoting yea and the percentageof Republicansvoting yea on a measure.6 Ideally,the votes used to measurepartypolarizationshould attemptto capture the sincere preferencesof membersratherthan any strategicbehavior.For this reason,I measurepartypolarizationon the finalrecordedvote takenon each measure in each chamber. Though other votes, such as those on particular amendments,may sometimes display higher party polarization,final votes are the most conducive to sincere voting on the issue at hand. As Mayhew(1991: 120) aptly points out, final votes "arethe ones that pose an up-or-downchoice between passing a bill or doing nothing .... Victoriousamendmentsare incorporatedin the final measures;others are left behind."7While measuringparty polarizationon a case-by-casebasis is the best way to establish a direct causal link and avoid inferenceproblemsinherent in aggregateanalyses,it does carry a caveat. Since party polarization is measured using votes on each proposal, 5 The data set contains49 cases of gridlockand 181 enactments. Ideally,the measureof partypolarizationshould capturethe degreeof distancebetweenthe parties. While it is difficultto measurepartydistanceat the individuallevel, the index of partydifference measureprovidesa good approximation.When aggregatedby Congress,the index of partydifference correlateswith the distancein partymedians (based on DW-NOMINATE scores, a common measureof memberideology)at .91 (Senate)and .87 (House) for the periodunder consideration. 7 In the data set, polarizationrangesfrom 0-97 (House) and 0-100 (Senate),with means of 33 (H) and 29 (S), and standarddeviationsof 26 (H) and 28 (S). 6 131 PoliticalResearchQuarterly significantproposalsthat did not receiverecordedvotes arenecessarilyexcluded from the analysis.However,analysisof these excluded cases suggests that their exclusion does not bias the findingsof this study8 For party seat division, I measure the percentageof seats held by voting membersof the President'spartyin a chamberat the time each proposalwas considered.In the Senate,since the President'spartyonly needs a three-fifthsmajority to end a filibusterwhile the non-presidentialpartyneeds a two-thirdsmajority to overridea veto, it is much more likely that largerproportionsof seats held by the President'spartywill help overcomegridlockthan it is that largerproportions of seats held by the non-presidentialparty will help overcome gridlock. This is also the case in the House, where the President'spartyneeds only a simple majorityfor passagewhile the non-presidentialpartyneeds a two-thirdsmajority to overridea veto.9 Finally,to test the divided governmenthypothesis, I code for unified versus dividedgovernment.10 Since the divided governmenthypothesisclaimsthat only unified party control of all three legislative actors-House, Senate, and President-can break gridlock,proposalsthat were consideredwhen the President's partyheld a majorityin both the House and the Senateare coded 0 for unified government(N = 58) and proposalsthat were consideredwhen the President's partydid not hold a majorityof seats in both the House and Senateare coded 1 for divided government(N = 172).11 8 Approximatelytwo-thirds of all proposals listed in CQ received recorded floor votes in both chambers.Using Poole and Rosenthal's(1997) coding scheme of 99 specific issues, I find that all of the issue areascoveredby the excluded cases are also presentamong the included cases. I also develop a rough estimate of party polarizationfor most (86 percent) of the excluded cases. A Chow test suggests if these cases were included they would have no significantimpact on the magnitudeor significanceof any of the key coefficients. 9 Presidentialpartyseat percentagerangesfrom 32-69 (House) and 37-61 (Senate),with means of 47 (H) and 49 (S), and standarddeviationsof 10 (H) and 7 (S). 10 While other variablessuch as leadershipinvolvementand presidentialposition are also relatedto legislativeoutcomes, they are generallymodeled as having an indirectimpact via the preferences of partymembersin Congress-a factorthat is alreadyaccounted for in the analysis.For example, Bondand Fleisher(2000) find thatwhen a Presidenttakesa position on a measurehe is more likely to draw more support from his own partythan from the opposition party,and when congressionalleaderssupport such measures,fellow partisansare more likely to support them and opposing partymembersare more likely to oppose them (thus affectingpartypolarization).I this study,I restrictmy focus to the effectsof polarizationratherthan its potentialcauses. 11 Consistentwith the divided governmenthypothesis, the 97th-99th Congressesin which Republicans held the White House and a majorityin the Senate,but not a majorityin the House, are coded as divided government.There is no significantdifferencein the results if two separate divided governmentdummy variablesare used instead (one for 97th-99th, another for "pure" divided government),indicatingthat the findings are in no way dependent on whether divided governmentis defined broadlyor narrowly(resultsavailablefrom the author). 132 andLegislative Gridlock PartyPolarization Since the dependentvariablein this study is dichotomous(a proposaleither fails or is enacted into law), I employ logistic regressionanalysis.The analysis thereforeevaluatesthe impact of the independentvariableson the likelihoodthat willfail to enacta givensignificantproposal("likelihoodof gridlock"). government FINDINGS Table1 presentsthe resultsof five logistic regressionmodels testingalternative partisanexplanationsfor gridlock.'2The first model estimatesthe effect of divided governmentalone on the likelihood of gridlock. As predicted by the divided governmenthypothesis, the coefficientfor divided governmentis positive and significant.The specific effect of an independentvariablein a logistic regressionmodel can be interpretedby translatingthe resultsinto probabilities. In this case, the results indicate that the presence of divided government increasesthe probabilityof gridlockby 12 percentagepoints-a fairlysubstantial amount.However,the divided governmentvariabledoes not actuallylead to any more cases being correctlypredicted. The next column in Table1 tests the relativestrengthof the partypolarization hypothesis versus the divided governmenthypothesis by adding variables measuringpartypolarizationand the interactionof partypolarizationwith presidentialpartyseat percentagein each chamber.The partypolarizationhypothesis predicts that higher party polarizationin a chamberincreasessystem-wide gridlock,but that the magnitudeof this increasediminishesto the extent that the President'spartyhas a largerpercentageof seats in that chamber.If this hypothesis is correct,the coefficientsfor partypolarizationshould be positive and the coefficientsfor the interactivetermsshould be negative. The results of the estimation of model 2 support the party polarization hypothesis.In both the House and Senate,the coefficientsfor partypolarization and for partypolarization'sinteractionwith presidentialpartyseat percentageare in the expecteddirection,and in the Senateboth variablesare statisticallysignificant. Furthermore,inclusion of the partypolarizationhypothesisvariablesprovides a statisticallysignificantboost in the model chi-squareand improves its predictiveefficiency On the other hand, the resultssuggest that divided government does not have any impact on gridlock over and above the effect of party polarizationand its interactionwith partyseat division. When these other party variablesare included in the estimation,the magnitudeof the divided government coefficientdrops and its significancevanishes. It is worth speculatingwhy,empirically,the partypolarizationand partyseat division in the Senateseem to have a more significantimpact on gridlockthan 12 I also ran the model with dummy variablesfor each Congressto test for any Congress-specific fixed effects.The fixed effectswere neitherjointly nor individuallysignificant,while my key variables remainedjointly significantand their signs and magnitudeswere not affected. 133 PoliticalResearchQuarterly 1 TABLE OFPARTY EFFECT VARIABLES ONGRIDLOCK, 1975-1998 IndependentVariables Model 1 Divided government .8560** (.4404) Model 2 .4347 (1.0402) Model 3 .2390 (.7294) Model 4 Model 5 .4945 (1.0037) Partypolarization (Senate) .1028** (.0584) .1372*** (.0446) .1568** (.0671) .1449*** (.0322) PartypolarizationX seats of President's party(Senate) -.0016* (.0012) -.0018** (.0009) -.0021** (.0012) -.0020*** (.0006) Partypolarization (House) .0453 (.0511) PartypolarizationX seats of President's party(House) PartypolarizationX divided government Constant -.0002 (.0011) Numberof cases Initial-2 log likelihood Model chi-square Reductionin error Aldrich-Nelsona pseudo-R2 -.0087 (.0220) -1.9859*** -4.0828*** -3.2619*** -3.4660*** -3.0646*** (.7175) (.9200) (.3656) (.4031) (.9960) 230 230 230 230 230 238.262 238.262 238.262 238.262 238.262 70.786*** 70.945*** 68.909*** 4.325** 78.443*** 30.63% 32.63% 26.53% 30.63% 0.00% .04 .51 .47 .47 .46 errorsin parentheses). coefficients Note:Entriesareunstandardized (standard *p < .10, **p< .05, ***p< .001 one-tailed. aUses Hagle and Mitchell(1992) correction. similarmeasuresin the House when both are includedin the model. One possibilityis thatwhen partisanconditionsin the Senatearesufficientto overcomethe institutionalobstaclesto enactmentin thatchamber,they are empiricallylikely to be sufficientin the House as well, but the reverseis not necessarilytrue. In this case,variablesmeasuredin the Senatewould be sufficientfor explainingalmostall of the partypolarizationeffectin both chambers.This scenariois consistentwith the empiricalfinding that partyvariablesare highly correlatedacross chambers (polarization.78, seats .87), and the factthatonly the Senateallowsfilibusters.'3 do not mean to suggest that passageof a proposalin the Senateguaranteesenactment.What I do suggest is if partypolarizationin the Senateis low enough to overcomea potential filibuster 13 I 134 Gridlock andLegislative PartyPolarization Since the insignificanceof the divided governmentvariablecould be attributable to mispecificationof the model, I estimate two alternativemodels with divided government.First, model 3 removes the insignificantHouse variables. Nevertheless,dividedgovernmentremainsinsignificant-unlike the partypolarization variablesfrom the Senate. Second, model 4 tests for the possibility that divided governmentis significantonly when partiesare polarizedby adding an interactionbetweenthese two variables(using Senatepolarization).However,the originalpartypolarizationhypothesisoutperformseven this reviseddivided governmenthypothesis. Finally,I estimate a reduced model of policy gridlock that includes only partypolarizationand its interactionwith presidentialpartyseats in the Senate. As in the previous three models, these two variablesare significantand retain their relativemagnitude.Furthermore,removalof the divided governmentvariable does little to diminish the explanatorypower of the model.14 Figure1 translatesthe resultsof this estimationinto probabilisticterms.The figuredisplays three lines, each representingthe effect of party polarizationon gridlockfor a differenthypotheticalpercentageof Senateseats held by the President'sparty:41 percent,51 percent,and 61 percent.When partypolarizationis non-existent (0 percent), the probabilityof gridlock for all three seat levels is equally unlikely-about .04. However,as party polarizationrises, the effect on gridlockis differentfor each of the threeseat levels. For the line labeled41 percent, greaterlevels of partypolarizationdramaticallyincreasethe probabilityof gridlock,as indicatedby the steep, positive slope. Specifically,gridlockbecomes more likely than enactment(probability> .5) for all levels of partypolarization above 48 percent.When the President'spartyhas a largerproportionof Senate seats-the line labeled51 percent,for example-party polarizationstill increases gridlock,but the magnitudeof its effectdiminishessomewhat.In this case, gridlock becomes more likely than enactmentonly for levels of party polarization above 71 percent. Finally,when the President'sparty has 61 percent of Senate seats, gridlock is always less likely than enactment (probabilityalways < .5), regardlessof the level of partypolarization. 14 (in conjunctionwith a particularpartyseat division),a similarlevel of partypolarizationand seat distributionin the House (as expected empirically)should be more than sufficientto achieve the simple majoritysupport that is needed for passagethere. But, if partypolarizationin the House is just barelylow enough to ensuresimple majoritysupportin the lower chamber(in conjunction with a particularpartyseat division), it is quite possible that a similarlevel of partypolarization and seat distributionin the Senatewill not be sufficientto overcomepotential filibustersin the upper chamber. While individualbill-level analysisis the most appropriatemethod for testing the partypolarization model, the results are similarwhen one conducts an aggregateanalysisof the model using Mayhew'sdata on the number of enactmentsper Congressand averagepartypolarizationscores for each Congress(Jones 1998). 135 PoliticalResearchQuarterly 1 FIGURE AND PARTYSEATDIVISION ESTIMATED EFFECTOF PARTYPOLARIZATION ON THEPROBABILITY OF GRIDLOCK (BASEDON TABLE1, EQUATION5) 0.90.8 - 0.7 r I I - 0.6- )) | 0.45 0.4 0.3 0. c .r 0.2 0.1 Le L 0 5 10 c, 15 c c c cc F .C'?-(? 20 '" rrr c ,? - ?' ,, 25 30 _ _ _____ ------ 35 40 45 50 55 60 Polarization Party (%) 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 41% of seats held by President'sparty 51% of seats held by President'sparty 61% of seats held by President'sparty Figure 1 also offersan explanationwhy divided governmentmight appear increase to gridlock when one does not control for party polarizationor party seat division. The regressionline representinga 41 percentminorityof seats for the President'spartyis necessarilyan exampleof divided government,while the line representinga 51 percentmajorityof seats for the President'spartyis more typicalof unified government.5In otherwords, divided governmentmay appear more prone to gridlocksimplybecausepartypolarizationis moreharmfulto legislationwhen the President'spartyhas fewerseats, not becauselegislative-executive agreementis precluded. CONCLUSION Basedon originalindividual-leveldata from 1975 through 1998, this article finds thatdividedgovernmentper se does not causegridlock.Instead,the results 15 Though this could also qualifyas a form of divided governmentif the President'sparty did not have a majorityof House seats. 136 andLegislative Gridlock PartyPolarization show that higherpartypolarizationincreasesgridlock,but that the magnitudeof this increasediminishesto the extent thata partyis closer to havingenough seats to thwartfilibustersand vetoes. Therefore,unified governmentis just as prone to gridlock as divided governmentwhen parties are highly polarized and neither partyhas a largemajority.On the otherhand, divided governmentis just as productive as unifiedgovernmentwhen partypolarizationis low or when one party has a veto-proof,filibuster-proofmajority. Based on the conventionalwisdom of the divided governmentargument, some reformershoping to alleviatelegislativegridlockhave advocatedchangesin the electoral system designed to promote unified government (see Sundquist 1992). Yet the resultsof this study suggest that adoptingsuch changes may not help to reduce gridlock, since unified governmentis not necessarilyany less prone to gridlock than divided government.A more effectivestrategyfor those who desire active governmentmay be to reduce the threatof filibustersby lowering the three-fifthscloture requirement.Ironically,however,lowering the cloture requirementrequiresa vote of two-thirdsof the Senate,a level of agreement that is unlikely to be reachedin the currentera of partypolarization. APPENDIX:MAJORLEGISLATIVE PROPOSALS 105thCongress bankruptcyrevisions managedcare partialbirth abortion supplementalapprop. 1997 budget reconcil.-spend.1998 budget reconcil.-taxes1998 defense authorization1998 supplementalapprop. 1998 defense authorization1999 higher education housing overhaul interet tax IRSrestructuring transportation 1Q4thCongress balancedbudget flag desecration StateDept., for. aid 1996-97 job training budget reconciliation1996 productliability regulatoryoverhaul term limits anti-terrorism/death appeals congressionalcompliance defense authorization1996 defense authorization1997 farmbill recissions 1995 health insurance immigration line item veto lobbying paperworkreduction safe drinkingwater shareholderlawsuits minimumwage hike telecommunications unfunded mandates welfarereform 103rdCongress campaignfinance lobbying 137 PoliticalResearch Quarterly EPAcabinetposition abortionclinic access Bradybill budget reconcil. 1993 defense authorization1994 defense authorization1995 economic stimuluspackage educationreauthorization family& medicalleave GATT Goals 2000 HatchAct independentcounsel motor voter NAFTA nationalservice NIH reauthorization omnibus crime savings& loan bailout unemploymentbenefits 102ndCongress crime bill educationgoals strikerreplacement urbanaid tax bill 1992 campaignfinancereform China-MFN motor voter familyleave gag rule middle class tax cut 1992 NIH reauthorization balancedbudget foreignaid auth. 1992-3 verticalprice fixing bankingoverhaul cable TV regulation civil rights defense authorization1992 DesertStormsupplemental energypolicy federalwaste compliance higher educationreauth. RTCfinancing Russianaid disasterrelief supplementalauth. 1991 surfacetransportation unemploymentbenefits use of force in Gulf 101st Congress civil rights HatchAct revisions textile & appareltrade campaignfinancereform age discrimination clean air contraaid defense authorization1989 defense authorization1990 disabilitiesact farmprograms housing programs legal immigrationrevision minimumwage increase Nicaraguaelection aid oil-spill liability Poland,Hungaryaid budget reconciliation1990 thriftbailout/reform vocationaleducation 100thCongress airportreauthorization catastrophichealth care GroveCity civil rights clean wateract contraaid G-R-Hrevisions defense authorization1989 droughtrelief fairhousing 138 andLegislative Gridlock PartyPolarization farmcredit FSLICrecapitalization defense authorization1988 budget reconciliation1988 highwayreauthorization homeless aid housing authorization omnibus drug omnibus trade plant closings/notice welfarereform foreignaid auth. 1982 highways/masstransit militarypay nuclearwaste omnibus farmbill budget reconciliation1983 budget reconcil.-spend.1982 social security supplementalapprop. 1982 tax cut voting rightsact 99th Congress clean wateract extension emergencyfarmcredit budget reconciliation1986 defense authorization1986 farmbill foreignaid authorization1985 Gramm-Rudman budget act reform immigration MXmissile appropriation MXmissile authorization South Africasanctions contraaid superfundreauthorization tax reform 96th Congress energymobilizationboard Alaskalands banking/NOWaccounts Chrysleraid educationdepartment food stamp spending cap FederalTradeCommission Genevatradeagreements nuclearenergy railroadderegulation syntheticfuels Taiwanrelations truckingderegulation windfallprofits 98th Congress immigration defense authorization deficit reduction housing authorization revenuesharing social security/medicare emergencyjobs program 95th Congress laborlaw revision campaignfinancing aid for education airlinederegulation Arabboycott civil servicereform clean air amendments emergencynaturalgas energydepartment financialdisclosure Humphrey-Hawkins minimumwage nationalenergyact 97th Congress oil allocation balancedbudget amend. defense authorization1983 budget reconcil.-taxes1982 139 PoliticalResearch Ouarterlv New YorkCity aid omnibus farm-foodbill public worksjobs reorganizationauthority social securityfinancing stimulustax cuts 1977 strip mining tax cuts 1978 waterpollution control 94th Congress clean air common-sitepicketing consumeragency farmsupports lobby reform naturalgas strip mining Vietnamcontingencyact arms sales/militaryaid educationaid emergencyhousing energyconservation& oil FECchanges food stamp price freeze northeastrail assistance New YorkCity aid public servicejobs public worksjobs railroadreorganization revenuesharing tax reduction tax revision Vietnamrefugeerelief voting rights REFERENCES Binder,Sarah.1999. "TheDynamicsof LegislativeGridlock,1947-1996."AmericanPoliticalScienceReview93: 519-36. PoliticsandPolicyfrom Brady,David, and CraigVolden. 1998. RevolvingGridlock: Carterto Clinton.Boulder,CO:WestviewPress. Cameron,Charles,William Howell, Scott Adler, and CharlesRiemann. 1997. "DividedGovernmentand the LegislativeProductivityof Congress, 19451994."Paperpresentedat the annualmeeting of the AmericanPoliticalScience Association,Washington,DC. Coleman,John J. 1999. "UnifiedGovernment,Divided Government,and Party AmericanPoliticalScienceReview93: 821-35. Responsiveness." Cutler,LloydN. 1988. "SomeReflectionsAbout DividedGovernment."Presidential StudiesQuarterly17: 485-92. Edwards,GeorgeC. III,AndrewBarrett,and JeffreyPeake. 1997. "TheLegislative Impactof Divided Government."American Journalof PoliticalScience41: 545-63. and the President'sQuest Fleisher,Richard,andJon R. Bond. 2000. "Partisanship for Votes on the Floor of Congress."In Jon R. Bond and RichardFleisher, eds., PolarizedPolitics:Congressand the Presidentin a PartisanEra.Washington, DC: CQ Press Hagle, TimothyM., and Glenn E. MitchellII. 1992. "Goodnessof Fit Measures for Probitand Logit."AmericanJournal of PoliticalScience36: 762-84. 140 andLegislative Gridlock PartyPolarization Jones, David R. 1995. "ExplainingPolicy Stabilityin the United States:Divided Governmentor Partisanshipin the House?"Paperpresentedat the annual meeting of the MidwestPoliticalScienceAssociation,Chicago. . 1998. "Partiesand the Volume of Law Production, 1947-1994." Presented at the annual meeting of the MidwestPoliticalScience Association, Chicago,IL. Kelly,Sean Q. 1993. "DividedWe Govern?A Reassessment."Polity25 :473-84. Kernell,Samuel. 1991. "Facingan OppositionCongress:The President'sStrategic Circumstance."In GaryW Cox and SamuelKerell, eds., ThePoliticsof DividedGovernment, pp. 97-112. San Francisco,CA:WestviewPress. A Indi1997. Solution to theEcological Problem: King,Gary. Inference Reconstructing vidualBehaviorFromAggregateData. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Kingdon,John W 1984. Agendas,Alternatives,and PublicPolicies.Boston:Little Brown. Krehbiel,Keith. 1998. PivotalPolitics.Chicago:Universityof ChicagoPress. Mayhew,David R. 1991. DividedWeGovern.New Haven:YaleUniversityPress. A Political-Economic HisPoole, KeithT. and HowardRosenthal.1997. Congress: toryof RollCallVoting.New York:OxfordUniversityPress. Z4ewLegislativeProcessesin the Sinclair,Barbara.1997. UnorthodoxLawmaking: U.S. Congress.Washington,DC: CQ Press. Sundquist,JamesL. 1988. "Needed:A PoliticalTheoryfor the New Eraof Coalition Governmentin the United States."PoliticalScienceQuarterly103: 61424. rev.ed. Washing_ . 1992. Constitutional Reformand EffectiveGovernment, ton, DC: BrookingsInstitution. AmericanPolitics Taylor,AndrewJ. 1998. "ExplainingGovernmentProductivity." Quarterly26: 439-58. Received:July 19, 1999 Acceptedfor Publication:July 5, 2000 davidjonesl @baruch.cuny.edu 141