Conflict and Cooperation: Divided and Unified Government during

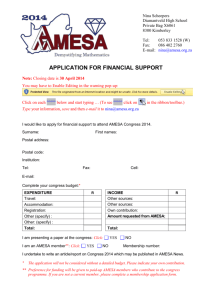

advertisement