Raising Cane: Cuban Sugarcane Ethanol's Economic

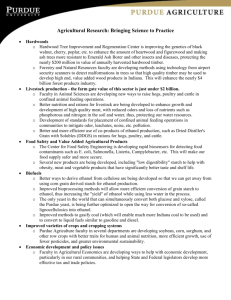

advertisement