exercise design 101 - Alberta Public Safety Training

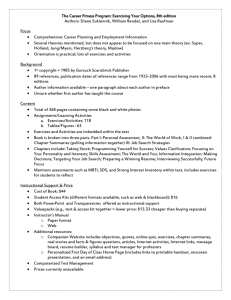

advertisement