packaging in the cosmetics industry

advertisement

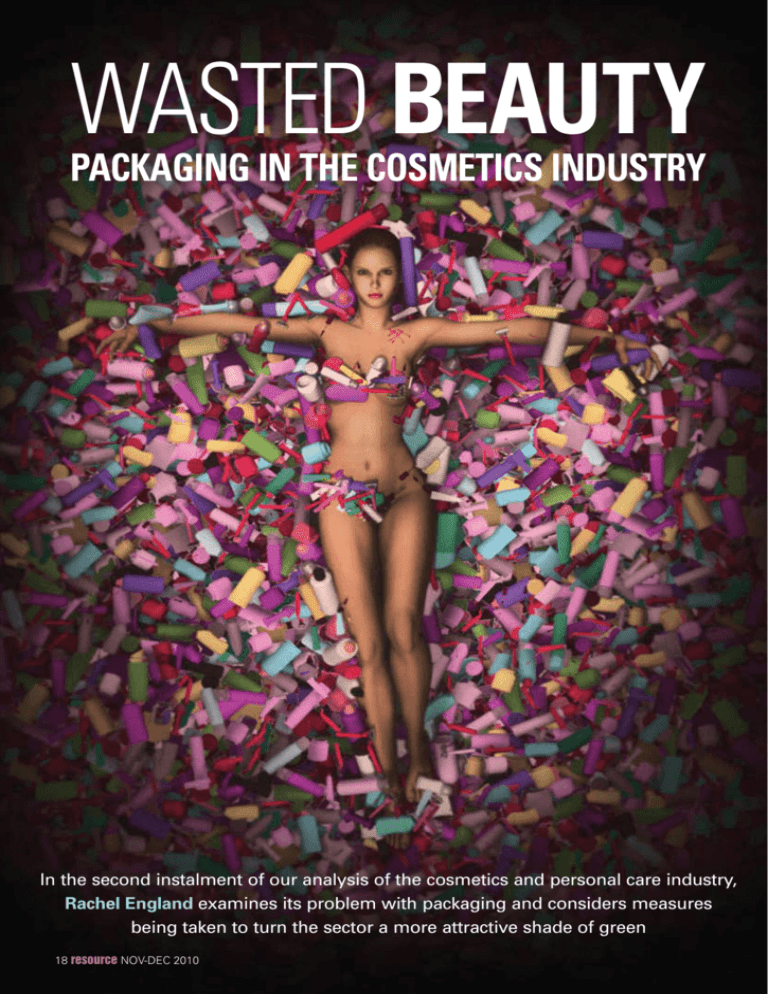

Wasted beauty packaging in the cosmetics industry In the second instalment of our analysis of the cosmetics and personal care industry, Rachel England examines its problem with packaging and considers measures being taken to turn the sector a more attractive shade of green 24 resource NOV-DEC 18 SEP-OCT 2010 2010 T aking care of ourselves is hard work. Diet, exercise, our psychological health... And then, in our appearance-centric world, our looks, too. Not as vital, many would argue, as ensuring good overall wellbeing, but certainly something that plays a role in everyday life. However, our desire to look (and smell) groomed to socially acceptable standards is not without its environmental consequences. The dozens of bottles and tubs adorning our bathroom shelves are made of increasingly scarce resources, and despite our best intentions, many of them are destined for landfills. Even the most basic personal care products, toothbrushes and razors, for example, pose an environmental headache. Around 23,000 tonnes of toothbrushes end up in US landfill every year (a figure that would be higher if more people changed their toothbrushes every three months as recommended), and each year two billion disposable razors are thrown away in the US. Razor company BIC introduced the ‘BIC Ecolutions Shaver’, a supposedly ‘green’ disposable razor that helps to counteract the environmental issues inherent in the product by utilising bioplastics, recycled materials and a commitment to a lower CO2 footprint, but even this cannot be recycled. As the website states, the razor ‘has to be thrown away in the same garbage bin as other shavers. Shavers are very difficult to recycle because they are too small and too light to attract the recycle [sic] industry’s attention.’ Foraying into the world of lotions and potions that make promises to de-wrinkle, soften, illuminate, glossify, plump and so on, it becomes apparent that this market is creating a lot of ugly waste in the name of beauty. Euromonitor reports that in 2008, the cosmetics industry created 120.8 billion units of packaging. Forty per cent of this was, as you might expect, rigid plastic (of varying plastic types, serving only to confuse consumers who would actively seek to recycle it). In the UK, this figure stands at around 55 per cent. There has been some progress with bioplastics in this area, but they’re often confused with regular plastics and can gum up recycling works if put in the plastic stream, and high water sensitivity means they’re not suitable for many products. Furthermore, companies looking for sustainable packaging alternatives are wary of the ethical implications of bioplastics: many reports suggest the crops used can drive up food prices and deplete supplies in developing countries. However, from early 2011 Procter & Gamble plans to package a range of its leading brands in a sugarcane-based plastic ‘sustainably’ grown in Brazil, “in order”, the company says, “to make the most meaningful improvement to our footprint that we can”. Still, while there are a number of drives in ‘greening’ packaging, the majority of companies seem slow to embrace environmental packaging strategies. Organic Monitor recently released a report stating that ‘cosmetic and ingredient firms are focusing on green formulation, resource “ efficiency and life-cycle assessments of their products when developing sustainability plans. Although companies are aware of the environmental impact of packaging, they have been slow to embrace sustainable packaging solutions.’ Indeed, Jane Bickerstaffe, Director of INCPEN, the Industry Council for Packaging and the Environment, illustrates this mentality: “I think to pick on a particular product group like cosmetics is meaningless”, she says. “It’s part of our lifestyle and it’s really for the government to decide these things. If we’re allowed to have [cosmetics], then packaging is the enabler that allows us to have them.” However, some pioneering companies take a more productive approach to the packaging issue. Plant-based toiletries company Aveda is the largest user of post-consumer recyclate plastic in the beauty industry, saving over 450 tonnes of virgin plastic each year. The company has also recycled 37 million polypropylene caps through its ‘Recycle Caps with Aveda’ campaign. Similarly, natural skin care specialist, Origins, runs ‘Return to Origins’, a recycling programme inviting customers to return Origins packaging in exchange for a free product sample. So far, over seven tonnes of cosmetic packaging have been saved in North America alone. Lush is another company striving to eradicate the environmental damage that looking good can do. It’s able to ‘get away’ with minimal packaging, consumer-returns incentives and, crucially, highly recycled/recyclable packaging because, as Ruth Andrade, Lush’s Environmental Officer, says, the company has its own shops. As such it’s able to manage the entire cradle-to-grave (or, in Lush’s case, cradle-to-cradle) process with environmental concerns at the forefront. “Our basic premise is this: We use the cheapest, safest, lightest packaging we can find, or we use no packaging at all”, she says, referring to Lush’s range of ‘naked’ bath bombs, shampoo bars and solid shower gels that come entirely unpackaged. “We use recycled pots and bottles where necessary, and have a returns policy that encourages customers to bring their packaging back.” Any of Lush’s trademark black pots recovered in the north of the country are sent to Remarkable, responsible for the ‘I used to be a...’ range of stationery, while any recovered in the south are simply recycled and reused again as black pots. The company has even set up its own recycling scheme. “Our aim is to collect all our own feedstock”, says Andrade. “So in addition to our own returned material, we’re now looking into partnerships with schools and councils, to use their discarded plastics for our packaging.” However, while Andrade recognises that operating entirely independently is an advantageous position, she’s always surprised by the reception the company receives from others in the industry: “Lots of companies think it’s quaint, almost amusing, that we do these things.” Indeed, Lush is admired for its naked products like bath bombs and shampoo bars and while other companies have taken to Although companies are aware of the environmental impact of packaging, they have been slow to embrace sustainable packaging solutions ” NOV-DEC SEP-OCT 2010 resource 19 emulating the company by stocking these items, they have not yet emulated the admirable packaging stance: Holland & Barrett also sells shampoo bars, which are packaged in cellophane and a cardboard box, and The Body Shop sells bath bombs, wrapped in shrink wrap. Nonetheless, Lush’s success does prove that the consumer is prepared to rethink cosmetics packaging. “Companies need to reassure customers that it’s okay to buy differently-presented products”, says Andrade. “My vision for the future of cosmetics is refill.” But some industry heads remain sceptical about the potential of refillable packaging. Bickerstaffe, for example, believes that the practicalities of it are “just crazy”. She says: “I know The Body Shop used to offer a refilling service some years ago, but it meant five minutes hanging around and a sticky bottle back. Even with a 10 per cent discount, only two per cent of customers took advantage of it, so it wasn’t worth having the clutter in the back of the store. It’s a nice idea, but in today’s lifestyles, people are living fast.” Indeed, Bickerstaffe has highlighted some problems of refillable packaging: time constraints, availability of refills and dexterity required are but some of the concerns of the consumer market, and extra shelf space, additional staffing and increased logistics present problems for companies, too. However, Dr Rhoda Trimingham, Lecturer in Industrial and Product Design at Loughborough Design School, is confident these factors can be overcome, and indeed, refillable packaging is present across virtually all markets in the Asia-Pacific region. “Understanding the relationship between the delivery mechanism, the consumer, the manufacturer and the brand allows the developer to custom build a refill system for the scenario in hand to avoid these potential problems”, she says. Indeed, Trimingham and her colleagues worked closely with the UK’s leading pharmacy, Boots, to develop a refillable packaging concept (in this case a sachet of concentrate mixed in a pump bottle with water, which Boots is currently finalising), which proved successful. “It was a hit with consumers”, she says. “It was perceived as high value and a number of testers said they would give it as a gift as it was packaged so nicely.” This idea of ‘gifting’ is crucial, and underpins the prevailing challenge the cosmetics industry faces in this area: the consumer mindset towards the appearance of a product designed to improve one’s appearance. As Bickerstaffe notes: “ “You could buy a basic-looking pot with a nice moisturiser in it, but it’s going to look fairly foul on your dressing table. I do think that it’s an emotional thing – that if you’re buying something to care for yourself you’re putting yourself down if you buy it in a brown paper bag.” Not everyone will agree with this view, but it does demonstrate the need for both consumers and manufacturers to change their perceptions towards beauty packaging. “It’s important to include designers who understand the personal care market when developing packaging”, says Dr Trimingham. “Value and ‘the gift experience’ can be designed into sustainable packaging just as it can be with any other sort of packaging. But there is always a point at which you have to hand responsibility to the consumer.” Encouragingly, though, some major cosmetics retailers are beginning to pay more attention to the packaging issue. Estée Lauder, for example, which owns Origins and Aveda, has a number of other accomplishments under its belt, including standardising the post-consumer recycled content of its shipping packaging to 90 per cent, reducing the size of Clinique’s promotional cartons by 15 per cent and using 80 per cent recycled content in all of its matte and satin anodised aluminium parts. Chief Environmental Officer at Estée Lauder, John Delfausse, has spoken out about the need for joined-up thinking between manufacturers, retailers, government and consumers, saying: “Manufacturers must adopt a totally different thought process at the design stage. It is the responsibility of industry and government working together to create an infrastructure that ensures that materials can be recaptured.” Let’s hope, then, that the thousands of beauty products that promise to slow down the aging process will eventually be packaged in such a way as to slow down the wasting process, too. Value and ‘the gift experience’ can be designed into sustainable packaging just as it can be with any other sort of packaging 20 resource NOV-DEC 2010 ”