Research summary: Teachers learning

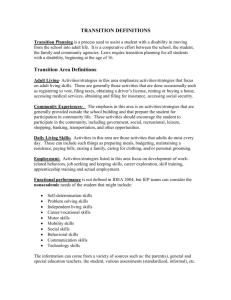

advertisement

Teachers are also not using the opportunities and resources that exist for professional development in the most optimal way. That has to do with control and with a mismatch between supply and demand. The main barriers to professional development are a lack of control over their own time (workload) and managers’ restrictions on teachers choosing their own professionalisation activities. The role of managers is crucial in several respects. Teachers feel that coordination should take place between a teacher and his or her supervisor and that control should be shared. A crucial part of this coordination is the appraisal cycle; our study established that teachers find it important to take advantage of the appraisal cycle to ask for professional development activities. Because teachers often do not consider informal learning as a form of professional development, it would be good to specifically ask about this activity. It is important that managers appreciate informal learning, also as evidence in performance appraisals. At the same time, we must ensure that teachers continue to experience sufficient autonomy. Attempts to enhance their professional development should not lead to external stimuli (such as rewards) taking the place of the control and influence of the teachers themselves. There also needs to be more customisation of professional development activities for teachers, supported by the schools and the government. Effective promotion of teacher competence requires more diverse and flexible forms of professionalisation. This relates to forms that are more in line with the stage of a teacher’s career, but also more practical and less rigidly structured forms. learn together through research. Forms in which joint educational development and learning together go hand in hand, as in design-oriented action research, also appear to be very effective. At least, this type of professional development is characteristic of nations with high-performing educational systems. But it is also the form of professionalisation that teachers have little opportunity to do. Therefore it seems important to structurally anchor this sort of development in the work of a team. Countries where teachers have the time and space for joint preparation, execution, evaluation and adjustment of education are the leaders in student performance. Research summary: Teachers learning An overview of teachers’ professional development Our research also found that teachers appreciate initiatives giving more control to teams, such as described in the legislative proposal to strengthen teachers’ positions. In short, there are still many opportunities waiting to be exploited, particularly in the areas of control of teams, the structural embedding of professional development in daily work and a team’s joint educational development. The professionalisation of teachers is a complex and often ambiguous matter. That is not to say that it is all doom and gloom with the quality of teachers and education in general, as some media would have us believe. It is a joint responsibility of politics, unions, management, boards and teachers themselves to explicitly draw attention to the many positive developments and interesting challenges posed to the teaching profession. This profession, which works intensively with young people, deserves recognition for its long-term, enormous social impact. Isabelle Diepstraten & Arnoud Evers (Eds.) In our international research, we found evidence for these flexible forms. Teachers in OECD countries especially appreciate forms of professional development that allow them to work together (e.g. invite colleagues to attend the lesson) and Wetenschappelijk Centrum Leraren Onderzoek LOOK Scientific Centre for Teacher Wetenschappelijk Centrum Leraren Research Onderzoek Open Universiteit look.ou.nl OpenUniversiteit Universiteit Open look.ou.nl look.ou.nl 5512427 Research questions, approach and study design The quality of education depends on the quality of teachers, so their professional development is crucial. But how do teachers see this development? Do they have time to develop themselves? And what does ‘professional development’ mean to them? The General Union of Education (De Algemene Onderwijsbond, AOb) asked the LOOK Scientific Centre for Teacher Research how primary, secondary and vocational school teachers can work to strengthen their own teaching skills. We examined the following questions: is part of the AOb website. Three themes were focused on during the online discussions and in the focus group: opportunities and resources for professional development, having a say (that is control) and whether the range of professional development activities meets teachers’ demands and needs. The questionnaire was distributed to teachers from primary, secondary and vocational schools and focused on control and on supply and demand. A total of 378 primary school teachers, 585 secondary school teachers and 185 vocational school teachers responded. 1 What opportunities and resources are available for teachers’ professional development and how do schools and teachers make use of them? 2 What opportunities do teachers have for having a say and how do they perceive this? 3 Do the range of opportunities for professional development connect with teachers’ needs? 4 What does teachers’ professional development look like in nations with high-performing educational systems? 5 How do similar professions develop to become more professional, specifically police officers and nurses? Below we describe each question, link them to the most important study conclusions and finish with a final conclusion. We have not only looked at consciously organised learning in which teachers earn a certificate or diploma, but we also looked at the ‘informal learning’ that occurs during daily work, such as a conversation with a colleague. These questions are examined on the basis of: − All the relevant policy documents from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science and social partners since the Action Plan for the Teaching Profession in the Netherlands published in 2008. − Relevant studies evaluating this policy. − Our own additional research from a focus group, online forum discussions and an extensive online questionnaire. Twenty-two teachers (mostly AOb consultants) from primary, secondary and vocational schools participated in the focus group. A wide range of teachers also spoke with one another on the online discussion forum that Opportunities and resources Individual schemes for professional development are clear and teachers like to use them. These schemes are the Teacher Education Subsidy (Tegemoetkoming Lerarenopleiding; TLO), the Teacher Scholarship (Lerarenbeurs) and the Doctoral Grant for Teachers (Promotiebeurs), of which the Teacher Scholarship is the most well known. Teachers are much less enthusiastic about the collective schemes because they are often vague and teachers have little control over them. To begin with, it is unclear precisely how much funding school boards now have for professional development, how it is allocated to the schools and how and whether schools actually use this money for professional development. It is also unclear how teachers themselves use the possibilities created by these collective schemes. This relates to how the right to use these schemes is defined in the collective agreement. The number of opportunities and resources teachers use for professional development is often underestimated because informal learning is often not taken into account. On the other hand, teachers do not optimally use the available options. This has to do with control (over one’s time and authorisation by management) and supply (the mismatch with the demand). Therefore this LOOK study pays extra attention to the issues of control and supply. Having a say Teachers quite often feel that they have a say in their personal development and feel competent to do so. At the same time, we concluded that teachers find it difficult to demand their rights when their managers ignore these rights. It also appears that teachers often do not know their formal rights. Teachers believe that coordination of personal professional development should primarily take place between a teacher and his or her manager, but coordination within the teams is also important. Teachers say as well that it is crucial to ask for professional activities in the appraisal cycle. The appraisal cycle plays an important role in strengthening their sense of control. Teachers will appreciate initiatives giving more control to teams, such as described in the legislative proposal to strengthen teachers’ positions. This proposal allows teams to develop their own teaching practices and to find out what qualities they need or what sort of professional development is needed in order to reach their goals. Supply and demand There is a qualitative mismatch between supply and demand; especially in vocational education, there is an unmet need for professionalisation. There is a need for more diversity and flexibility in the professional range. This requires professional development activities customised for the teachers and supported by the schools and the government. If teachers want to provide good and up-to-date education, it is important that they continue to evolve. Effective promotion of teachers’ competence therefore requires different and more flexible forms of professionalisation. Professional development abroad Teachers in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries greatly appreciate opportunities to work with one another through research and collaborative learning. Forms in which joint educational development and learning together go hand in hand, as in designbased action research (research aimed at approving teachers own educational practices), also appear to be very effective. At least, this type of professional development is characteristic of nations with high-performing educational systems. But it is also the type of professionalisation that teachers have little opportunity to do. Therefore it seems important to structurally anchor this sort of development in the work of a team. Countries where teachers have the time and space for joint preparation, execution, evaluation and adjustment of education are the leaders in student performance. Separate professionalisation hours, money (whether individual budgets or not), type of suppliers: all these things seem much less important. Professionalisation seems to be particularly effective as a natural part of the work or, better said, of teamwork. This also ensures control and autonomy, not in the sense of the individual teacher as a person but as a professional in a professional environment. Professional development in similar occupations An important difference from teachers is that both police officers and nurses have a daily transfer of tasks to colleagues. This ensures that there is automatically time for substantive contact and consultation with colleagues. This is not structurally integrated into teachers’ daily work and in the teaching profession the combination of professional activities and daily work seems to be most problematic. Time plays less of a factor when police officers and nurses schedule professionalisation. We also noticed how well the nursing profession is organised; there is an active professional association which works in conjunction with the union Nu’91. Final conclusions When teachers think about opportunities and resources for professional development, they often think of formal courses and training. The informal learning that teachers rely on in their everyday work is not often recognised as a significant opportunity for the development of their profession, though teachers often praise that informal, everyday learning in the workplace as the most useful. Research questions, approach and study design The quality of education depends on the quality of teachers, so their professional development is crucial. But how do teachers see this development? Do they have time to develop themselves? And what does ‘professional development’ mean to them? The General Union of Education (De Algemene Onderwijsbond, AOb) asked the LOOK Scientific Centre for Teacher Research how primary, secondary and vocational school teachers can work to strengthen their own teaching skills. We examined the following questions: is part of the AOb website. Three themes were focused on during the online discussions and in the focus group: opportunities and resources for professional development, having a say (that is control) and whether the range of professional development activities meets teachers’ demands and needs. The questionnaire was distributed to teachers from primary, secondary and vocational schools and focused on control and on supply and demand. A total of 378 primary school teachers, 585 secondary school teachers and 185 vocational school teachers responded. 1 What opportunities and resources are available for teachers’ professional development and how do schools and teachers make use of them? 2 What opportunities do teachers have for having a say and how do they perceive this? 3 Do the range of opportunities for professional development connect with teachers’ needs? 4 What does teachers’ professional development look like in nations with high-performing educational systems? 5 How do similar professions develop to become more professional, specifically police officers and nurses? Below we describe each question, link them to the most important study conclusions and finish with a final conclusion. We have not only looked at consciously organised learning in which teachers earn a certificate or diploma, but we also looked at the ‘informal learning’ that occurs during daily work, such as a conversation with a colleague. These questions are examined on the basis of: − All the relevant policy documents from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science and social partners since the Action Plan for the Teaching Profession in the Netherlands published in 2008. − Relevant studies evaluating this policy. − Our own additional research from a focus group, online forum discussions and an extensive online questionnaire. Twenty-two teachers (mostly AOb consultants) from primary, secondary and vocational schools participated in the focus group. A wide range of teachers also spoke with one another on the online discussion forum that Opportunities and resources Individual schemes for professional development are clear and teachers like to use them. These schemes are the Teacher Education Subsidy (Tegemoetkoming Lerarenopleiding; TLO), the Teacher Scholarship (Lerarenbeurs) and the Doctoral Grant for Teachers (Promotiebeurs), of which the Teacher Scholarship is the most well known. Teachers are much less enthusiastic about the collective schemes because they are often vague and teachers have little control over them. To begin with, it is unclear precisely how much funding school boards now have for professional development, how it is allocated to the schools and how and whether schools actually use this money for professional development. It is also unclear how teachers themselves use the possibilities created by these collective schemes. This relates to how the right to use these schemes is defined in the collective agreement. The number of opportunities and resources teachers use for professional development is often underestimated because informal learning is often not taken into account. On the other hand, teachers do not optimally use the available options. This has to do with control (over one’s time and authorisation by management) and supply (the mismatch with the demand). Therefore this LOOK study pays extra attention to the issues of control and supply. Having a say Teachers quite often feel that they have a say in their personal development and feel competent to do so. At the same time, we concluded that teachers find it difficult to demand their rights when their managers ignore these rights. It also appears that teachers often do not know their formal rights. Teachers believe that coordination of personal professional development should primarily take place between a teacher and his or her manager, but coordination within the teams is also important. Teachers say as well that it is crucial to ask for professional activities in the appraisal cycle. The appraisal cycle plays an important role in strengthening their sense of control. Teachers will appreciate initiatives giving more control to teams, such as described in the legislative proposal to strengthen teachers’ positions. This proposal allows teams to develop their own teaching practices and to find out what qualities they need or what sort of professional development is needed in order to reach their goals. Supply and demand There is a qualitative mismatch between supply and demand; especially in vocational education, there is an unmet need for professionalisation. There is a need for more diversity and flexibility in the professional range. This requires professional development activities customised for the teachers and supported by the schools and the government. If teachers want to provide good and up-to-date education, it is important that they continue to evolve. Effective promotion of teachers’ competence therefore requires different and more flexible forms of professionalisation. Professional development abroad Teachers in OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries greatly appreciate opportunities to work with one another through research and collaborative learning. Forms in which joint educational development and learning together go hand in hand, as in designbased action research (research aimed at improving teachers own educational practices), also appear to be very effective. At least, this type of professional development is characteristic of nations with high-performing educational systems. But it is also the type of professionalisation that teachers have little opportunity to do. Therefore it seems important to structurally anchor this sort of development in the work of a team. Countries where teachers have the time and space for joint preparation, execution, evaluation and adjustment of education are the leaders in student performance. Separate professionalisation hours, money (whether individual budgets or not), type of suppliers: all these things seem much less important. Professionalisation seems to be particularly effective as a natural part of the work or, better said, of teamwork. This also ensures control and autonomy, not in the sense of the individual teacher as a person but as a professional in a professional environment. Professional development in similar occupations An important difference from teachers is that both police officers and nurses have a daily transfer of tasks to colleagues. This ensures that there is automatically time for substantive contact and consultation with colleagues. This is not structurally integrated into teachers’ daily work and in the teaching profession the combination of professional activities and daily work seems to be most problematic. Time plays less of a factor when police officers and nurses schedule professionalisation. We also noticed how well the nursing profession is organised; there is an active professional association which works in conjunction with the union Nu’91. Final conclusions When teachers think about opportunities and resources for professional development, they often think of formal courses and training. The informal learning that teachers rely on in their everyday work is not often recognised as a significant opportunity for the development of their profession, though teachers often praise that informal, everyday learning in the workplace as the most useful. Teachers are also not using the opportunities and resources that exist for professional development in the most optimal way. That has to do with control and with a mismatch between supply and demand. The main barriers to professional development are a lack of control over their own time (workload) and managers’ restrictions on teachers choosing their own professionalisation activities. The role of managers is crucial in several respects. Teachers feel that coordination should take place between a teacher and his or her supervisor and that control should be shared. A crucial part of this coordination is the appraisal cycle; our study established that teachers find it important to take advantage of the appraisal cycle to ask for professional development activities. Because teachers often do not consider informal learning as a form of professional development, it would be good to specifically ask about this activity. It is important that managers appreciate informal learning, also as evidence in performance appraisals. At the same time, we must ensure that teachers continue to experience sufficient autonomy. Attempts to enhance their professional development should not lead to external stimuli (such as rewards) taking the place of the control and influence of the teachers themselves. There also needs to be more customisation of professional development activities for teachers, supported by the schools and the government. Effective promotion of teacher competence requires more diverse and flexible forms of professionalisation. This relates to forms that are more in line with the stage of a teacher’s career, but also more practical and less rigidly structured forms. learn together through research. Forms in which joint educational development and learning together go hand in hand, as in design-oriented action research, also appear to be very effective. At least, this type of professional development is characteristic of nations with high-performing educational systems. But it is also the form of professionalisation that teachers have little opportunity to do. Therefore it seems important to structurally anchor this sort of development in the work of a team. Countries where teachers have the time and space for joint preparation, execution, evaluation and adjustment of education are the leaders in student performance. Research summary: Teachers learning An overview of teachers’ professional development Our research also found that teachers appreciate initiatives giving more control to teams, such as described in the legislative proposal to strengthen teachers’ positions. In short, there are still many opportunities waiting to be exploited, particularly in the areas of control of teams, the structural embedding of professional development in daily work and a team’s joint educational development. The professionalisation of teachers is a complex and often ambiguous matter. That is not to say that it is all doom and gloom with the quality of teachers and education in general, as some media would have us believe. It is a joint responsibility of politics, unions, management, boards and teachers themselves to explicitly draw attention to the many positive developments and interesting challenges posed to the teaching profession. This profession, which works intensively with young people, deserves recognition for its long-term, enormous social impact. Isabelle Diepstraten en Arnoud Evers (Eds.) In our international research, we found evidence for these flexible forms. Teachers in OECD countries especially appreciate forms of professional development that allow them to work together (e.g. invite colleagues to attend the lesson) and Wetenschappelijk Centrum Leraren Onderzoek LOOK Scientific Centre for Teacher Wetenschappelijk Centrum Leraren Research Onderzoek Open Universiteit look.ou.nl OpenUniversiteit Universiteit Open look.ou.nl look.ou.nl 5512427