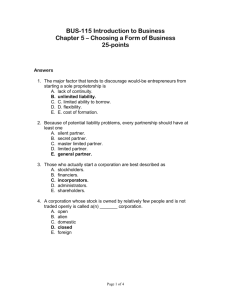

F21-4-96

advertisement