MODULE 7 Skills Development

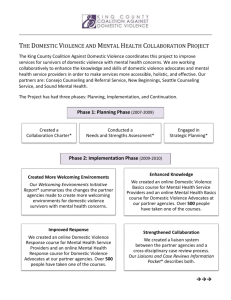

advertisement