Research Paper The Minerva Christ – A nude Christ or a nude

advertisement

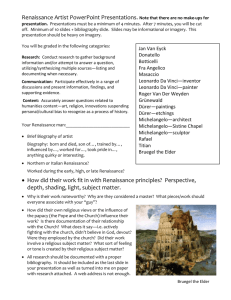

Research Paper The Minerva Christ – A nude Christ or a nude Michelangelo? Harvard University Extension School 11 January 1999 Carlos Rafael L. Souza 4 Davis Ave #2C Brookline, MA 02445 (617) 734-4419 I. Introduction The male nude is a constant in Michelangelo’s work. From his Cupid, in the beginning of his sculptor’s career to the painting of the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, it appears in profusion in almost all of his works. This paper is about one of his pieces: the Minerva Christ made to be put in the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, in Rome. My topic is the Christ’s nudity in this work. Why did he have to be nude? An answer to this question may add some new insights into the complex personality of Michelangelo, and this is why it is worth studying. My thesis is that Michelangelo depicted a nude Christ because of both conscious influences and unconscious motivations. Most of the works hitherto focus on the conscious aspects, external to the artist. My work will be original because I will use the psychoanalytical tool to identify some unconscious elements in the Minerva Christ. These elements will, then, be added to what I consider the critical external influences in Michelangelo: the religious preaching of friar Girolamo Savonarola in Florence and the impact on Michelangelo of the neo-platonic philosophy. If I successfully prove my thesis, it may be applied, in other studies, to a comprehensive understanding of the nude in Michelangelo’s work. II. The Work On June 14, 1514, Michelangelo signed a contract with the patrons of one of his most controversial works: a full size Christ to be put in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. This work became known as the Minerva Christ (Figure 1 – Souza - 1 Annex I). The patrons were a group lead by the Porcari family, from Rome, and their influence on the work can be inferred to be restricted to the terms of the contract. They were in Rome while Michelangelo was in Florence during the manufacturing of the sculpture, and there is no evidence of exchange of letters among them during the five-year period the artist took to finish it. The terms of the contract 1 can be summarized in the following five elements: it was supposed to be a marble sculpture of Christ, life-size, nude, holding a cross in his arms and in a position that would please Michelangelo. For the purpose of this paper, the aspect of being a nude Christ is most relevant. In the original Italian text the word used for nude was “ignudo,” which may not have the connotation it has nowadays. According to Steinberg, men without their shirts could be considered “ignudi.”2 However, it is difficult to believe that the patrons expected to have a full nude Christ. I would rather agree with Agoston3 that this was probably something requested by Michelangelo, who already had a model in his mind and who may not have wanted any litigation because of its nature. The work was finished in 1520 and sent to Rome. Michelangelo did not participate in its installation, which was left to his assistants. In the correspondence they exchanged it is clear that Michelangelo concentrated his efforts in the abdominal part of the statue, leaving the rest to his assistants. It is clear that it was the artist’s original intent to have the figure of Christ completely naked. Some years after its installation, however, still during the sixteenth 1 Laura Agoston. Michelangelo's Christ : the Dialectics of Sculpture. (Harvard PhD Dissertation, 1993.), p. 5, based on Le Lettere di Michelangelo Buonarroti coi Ricordi ed I Contrati Artistici (Florence, 1875), pp. 641-642. Souza - 2 century, the work suffered a radical mutilation. Christ’s originally visible genitalia were covered by a gross brass drapery (Figure 2 – Annex I). This may have been due to the moralizing movement started at the Council of Trent in which all lasciviousness had to be removed from religious places.4 A careful look at the work reveals some details that will be very important for my interpretation. Strangely enough for a work of Michelangelo, this sculpture does not give an impression of movement, but shows a static Christ. It seems that Michelangelo did not want to point to any action Christ was doing at that moment, but to the state in which he was. The piece is very simple in its elements: besides the Christ and the cross there are also a reed, a sponge and a rope. They are all items related to his Passion, but their presence in his hands motivated a debate on the religious meaning of the sculpture. There are at least four different iconographic interpretations of the Minerva Christ.5 Firstly, Wolfgang Lotz considers it the resurrected Christ. Secondly, Henry Thode and Erwin Panofsky see it as a representation of the man of sorrows (thus before his death). Charles de Tolnay and Colin Eisler combined the two interpretations above. Finally, Gerda Panofsky proposed a new approach, considering it the new Adam. I lean toward Lotz’s interpretation because the statue did not originally have marks on the back of Christ, denoting he was beaten, or any appearance of suffering in his face. Also, by analyzing 2 3 4 5 Leo Steinberg. The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion. (2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), p. 146. Agoston, op. cit., p. 6. Anthony Blunt. Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1600. (London; New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), p. 118. Agoston, op. cit., is the one who originally compiled all four approaches in her dissertation. Souza - 3 other works of art of that period,6 there are at least two instances where the figure of Christ is similar to the one Michelangelo used, holding a cross in his arms, clearly denoting a risen Christ. Yet the fact that the Minerva Christ is fully nude makes it very unusual. It is fairly common to find in Renaissance Italy nude figures of Christ during his crucifixion. A living nude Christ, not in a context of suffering, was very rare, if not unique. I have already mentioned above that the sculpture is in a static position denoting a state of being. The following is a singular explanation for it, originally presented in the Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography 7, with which I strongly agree: for Michelangelo, Christ was the incarnation of God. His death on the cross was the moment in which he called to himself the sins of all humankind. In his resurrection, his body was transformed and all sins were redeemed. The risen Christ had purified human nature, which was once corrupted by the original sin in the lapse of men. Therefore, the fallen shame related to human nudity was not in him anymore. He would not have to hide any part of his body as indecorous or impure. He was freed from the burden of his clothes as the means to deprive others from seeing his shameful nature. Michelangelo would not, and did not, show in any of his works a dead, or dying, Christ nude. This seems to be possible only for a risen Christ. If we put the Minerva Christ in perspective within Michelangelo’s total work, the importance of his nudity becomes clearer. I consider the Minerva Christ 6 James Clifton. The Body of Christ in the Art of Europe and New Spain, 1150-1800. (Munich; New York: Prestel, 1997). In this work there are reproductions of the paintings of Lambert Lombard: Scenes of Passion and Resurrection of Christ (1541), p. 90, and Girolamo da Santacroce: The Resurrection (1525), p.93. Both Christs are in the same position as Michelangelo’s Minerva Christ. Souza - 4 to be the apex of the humanistic experience of Michelangelo. Before it, he was free to depict male nudity in many of his pieces. Both mythological and religious subjects allowed it. Even in the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling he seemed to be completely at ease with the nude. Four of his sculptures from this period also clearly depicted the sexual organs of male figures: Cupid, Bacchus, David, and The Sleeping Captive. However, when he was portraying Christ, he seemed to be more careful. His first Pietà, from the beginning of the sixteenth century, shows a dead Christ covered in his indecorous parts. In the period after the Minerva Christ, Michelangelo’s work became much more religious than it once was, especially with the drawings for Vittoria Colonna and the late Pietàs. What happened during the decade of 1520 that marked the artist so deeply? Two important events took place during this decade: the beginning of the Protestant Reformation (1521) and the subsequent Sack of Rome (1527). Michelangelo was a very religious man, as we will see later on. Also, as a famous artist he had free access to the pope, whoever he would be. In other words, he lived in the heart of the Catholic Church and was deeply influenced by it. He may have been moved by the excommunication of Martin Luther in 1521, and the way it quickly undermined the power of the Church in Europe. The Sack of Rome was surely a consequence of the weakness of the papacy, and Michelangelo attached himself to more solid religious grounds by joining, together with his newly met spiritual mentor Vittoria Colonna, a group in Rome headed by a cardinal – the “spirituali.” His humanistic/neo-platonic background 7 Helene Roberts (ed.). Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography : Themes Depicted in Works of Art. (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1998.), p. 643. Souza - 5 seemed not to be his support anymore. Michelangelo’s work became much more focused on religious symbols. Most of Michelangelo’s subsequent works, at least the public ones, are much more careful in dealing with nudity. The Conversion of Paul and the Crucifixion of Peter show no nudes at all. None of the late Pietàs show a nude Christ. The Rondanini Pietà may leave this impression, but it was not finished, so it is hard to interpret it. The only place where the nude is still present, and in profusion, is in the Last Judgment. However, I am inclined to agree with Blunt that “they are heavy and lumpish, with thick limbs, lacking in grace,”8 very different from the grace of, for example, Adam in the Creation of Man. In addition, Michelangelo showed a consistent concern for the representation of the figure of Christ during his work. The only occurrences of Christ’s genitalia in his work are in four Madonna sculptures and in the Minerva Christ. In the Madonnas, the baby Jesus is without clothes, a very common and innocent motif. However, the only full-grown Christ’s penis is in the Minerva Christ. In summary, the Minerva Christ represents a unique piece in Michelangelo’s work as well as in Renaissance Italy. Its nudity epitomizes a strong theological position assumed by Michelangelo: the risen Christ has freed us from the shame of our indecorous parts. Therefore, he may be portrayed with no clothes at all. However, I believe that it embodies not only this theological premise, but also all the conscious influences and unconscious motivations that will be further developed in the following two sections. Souza - 6 III. The Conscious Influences In this section of the paper, I will analyze what I consider the two most important influences over Michelangelo: Savonarola and Ficino. I also want to relate their impact on him with the Minerva Christ and with the nudity of Christ. I am calling them conscious, external influences in contrast to the unconscious, hidden stimuli from within the artist, which will be fully covered in Section IV. Before he celebrated his twentieth birthday, Michelangelo had already experienced a deep immersion into the humanist tradition through his mentor Marsilio Ficino, as both lived in the court of Lorenzo de Medici. On the other hand, Condivi, one of his most important biographers, recorded the following statement by Michelangelo just before his death: “More than fifty years later… he could still remember the friar’s voice.”9 This is a clear reference to the friar of the Cathedral of Florence at the end of the century, Girolamo Savonarola, who was a prominent figure in the Florentine life. It is, as well, strong evidence of his influence in the formation of Michelangelo’s personality. What did that “voice” say? Savonarola was a very controversial spiritual leader. He started his preaching with an apocalyptic discourse: the Catholic Church had to be renewed, Italy had to be punished for its moral shortage, and the world would then come to 8 9 Blunt, op. cit., p. 65. Ascanio Condivi. The Life of Michelangnolo Buonarroti. (Trans. by Charles Holroyd. London: Duckworth, 1904), p. 105 (quoted by James Saslow in The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation by James M. Saslow, p. 10). Souza - 7 its end.10 He believed he was chosen by God to prepare the people of Florence for such calamity. He preached a very strict moral code, exposing the Florentines’ sins, out of which sodomy (meaning male homosexuality) was the worst. At that time sodomy was, besides a sin, a criminal offense and had to be prosecuted by the local authorities. As I will further develop later on, Michelangelo had a strong homosexual orientation, and hearing such discourse from the Church officials must not have been easy for him. Such restriction, however, never prevented him from using the male nude in his works from the beginning as a sculptor. Yet, deep inside, the idea of sin was, little by little, building a sense of inadequacy and nonconformity with the accepted moral standards. This would become very clear in his later poems, which although explicitly representing love toward other men, always carried the conscience of an eminent punishment by God.11 Savonarola, closer to the end of his life, changed the tone of his discourse from the end of the world to its transformation through politics. He became very famous by performing the role of a Florentine ambassador towards the invading emperor Charles V, from France. His republican ideas, however, did not please the local ruling power, and he was, because of them, eventually excommunicated from the Catholic Church and burnt at the stake. He also bothered the local artists and intellectuals with his moral attacks on their behavior. In at least two instances, he supported public bonfires known as Bruciamenti delle Vanita (bonfire of vanities) in which books considered profane, as well as some 10 Donald Weinstein. Savonarola and Florence; Prophecy and Patriotism in the Renaissance. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1970), pp. 61, 65, 144-145. Souza - 8 indecorous paintings, were destroyed. Even daily things like cosmetics, mirrors, false hair, playing cards and dice were burnt, causing a profound dissatisfaction in some educated people.12 There is no evidence of the impact such bonfires had on Michelangelo, but he surely saw them and they must have caused some reactions in him. Finally, Savonarola definitely influenced Michelangelo with his opinion about the proper art, the one that he would not burn as indecorous: he believed religious paintings could work as books for women, children and men who could not read. In a passage from Francisco de Hollanda’s Roman Dialogues, Michelangelo shows his opinion about the proper role of an artist. It seems he assimilated the spirit of Savonarola’s preaching. He was considering himself as someone chosen by God to perform his artistic work: … in order to imitate to some extent the venerable image of our Lord it is not sufficient merely to be a great master in painting and very wise, but I think that it is necessary for the painter to be very good in his mode of life, or even, if such were possible, a saint, so that the Holy Spirit may inspire his intellect.13 And in another part: And therefore if God the Father willed that the ark of His Covenant should be well ornamented and painted, how much more study and consideration must He wish applied to the imitation of His Serene Face and that of His Son and Lord… Frequently the images badly painted distract and cause devotion to be lost, at least in those who possess little; and, on the contrary, those that are divinely painted provoke and lead even those who are little devout and but little inclined to worship to contemplation and tears…14 11 12 13 14 See p. 14. Jane Turner (ed.). The Dictionary of Art. (New York: Grove's Dictionaries, 1996), p. 894. Condivi, op. cit, p. 319. Ibid., p. 320. Souza - 9 Michelangelo was assuming his artistic duty almost as a prophetic one, appointed directly by God in order to instigate the devout worship. I do believe this is the same spirit that led him in the sculpting of the Minerva Christ. Otherwise, the words above can only be interpreted in a very cynical connotation. Yet, despite their godly appearance, they hide another religion, different from Christianity, moving inside Michelangelo: neo-platonism. His mentor in this field was Marsilio Ficino. Humanism, the restoration of the classical values as proposed in the previous century by Petrarch and Boccaccio, found faithful followers in Florence one hundred years before Michelangelo. Some chancellors of the Republic of that time, such as Salutati, Bruni and Bracciolini, planted the seed that flourished all over Europe. However, Michelangelo was deeply influenced by a branch of humanism, neo-platonism, which may be regarded as humanist, though it kept the metaphysics introduced by Plotinus in Greece before the Common Era. As both Michelangelo and Marsilio Ficino lived in the court of Lorenzo de Medici during the same period at the end of the fifteenth century, the former may have participated in the informal Platonic Academy in Florence, led by Ficino, who proposed a synthesis of philosophy and theology. Based on Plotinus, he built a new paradigm for philosophy, art and mysticism. For the former, “art could not reveal the highest reality, but must be superseded by philosophical understanding and mystical experience.”15 Ficino also recovered some concepts in Plotinus’ metaphysics, which gave neo-platonism its aura of a semi-religion. 15 Turner, op. cit., p.750, summarizing Plotinus’ ideas present in the Ennead (V.viii.1). Souza - 10 God was regarded as the One, and humans should surpass material reality to find him. However, it was the concept of beauty, as developed by Ficino, that was probably the strongest attracting factor for Michelangelo. God, for the neoplatonists, in his glory, decided to be made known to men through beauty. Any form of beauty, then, may be a gate to the divine sphere. Once in such a realm, the soul could be in contact with God himself, and through this apparition love would be produced and would work as the linkage between humanity and divinity. Michelangelo’s work may be regarded as the attempt to embody such beauty, especially the one of human bodies. Blunt attributed to Michelangelo the realization that beauty would be a reflection of God in the material world, and that the human figure is God’s most clear manifestation.16 For me, based on this statement and that God was incarnated in Christ, the Minerva Christ turned out to be a unique chance for Michelangelo to make the following point: a beautiful Christ unites the marvel of men and God in one entity. I think this is what he had in mind during the sculpting of the Minerva Christ. Yet, it had to be a risen Christ to portray such beauty. A dead or suffering Christ would mix the supernatural attraction for him with the repulsion caused by the sin put on him during the redeeming achievement. Therefore, the Minerva Christ was a unique chance for Michelangelo to depict a glorious Christ, fully human, yet risen and closer to God. 16 Blunt, op. cit., p. 62. Souza - 11 Together with these above-mentioned two influences of Savonarola and Ficino, I believe Michelangelo was also influenced by hidden stimuli unconsciously produced. IV. The Unconscious Motivations Michelangelo’s personality is very complex. Therefore, the analysis of its conscious influences may not uncover all of its riches. This section of the paper will take a psychoanalytical approach to his personality in order to bring more light to the interpretation of the Minerva Christ. Sigmund Freud proposed a division of human personality into three main parts: the id, the ego and the super-ego. The id is our part related to the instinctual forces from our animal legacy. It embodies all the drives moving in us, out of which the libido, or sexual energy, is the strongest. The super-ego is the part of us that reproduces the social limitations to our conduct. It is our internal repository of the moral code of the society we live in. It is a built-in judge telling men what they should or should not do. The ego is the resulting interaction of the id and the super-ego. The ego is our selves.17 Michelangelo’s super-ego was carefully molded in him by the combined influence of Savonarola and the neo-platonic legacy. Inside him there was condemnation and repression of his innermost feelings. Saslow states that he was always concerned about his public image and never wanted to see it related 17 Sigmund Freud. The Ego and the Id. (London: Hogarth Press, 1950), pp. 19-53. Souza - 12 to morally reprehensible acts like sodomy, for example.18 This may also be inferred from poem No. 56. According to Gilbert, in it “Michelangelo’s fears that people would apply their own standards to him were all too justified.”19 Michelangelo’s id may also be inferred from his work and biography. Many scholars consider him a homosexual, although all agree that there is no evidence of any genital relationships with other men. He was not like Leonardo da Vinci, who carefully hid his emotional life from the public. On the contrary, he made it very open, especially through his poetry. However, some scholars surmise that he had a more intimate relationship with at least two men: Gherardo Perini and Tommaso Cavalieri.20 In the many dozens of poems written by Michelangelo, clearly autobiographical, some deserve our attention in order to confirm his relationship with Perini. No. 36 is the first of them to clearly relate his love to another man, though there is no mention of Perini. Saslow suggests, based on Charles de Tolnay, that it was he, and that the former poems directed to an unnamed figure were written for him. At the same time, within these first poems, Michelangelo’s super-ego is already present: sin and vengeance, according to Saslow, may be found at least twice21, in poem 22: Earth has claws out for every creature born, and mortal beauty must dwindle day by day. The lover knows; he struggles - just the same fails. 18 19 20 21 James Saslow. Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in Art and Society. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), p.48-49. Michelangelo Buonarroti. Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo. (translated, with foreword and notes, by Creighton Gilbert; edited, with biographical introduction, by Robert N. Linscott. 3rd ed. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980), p. xvi (Translator’s Foreword). Saslow, The Poetry of Michelangelo, op. cit., p.13. Ibid., p. 13. Souza - 13 Sin and vengeance are blood-brothers sworn.22 and in No. 32: I live for sinning, for the self that dies, My life being mine no more, this life in sin. Heaven made me good; I dug the pit I'm in.23 Another clear object of Michelangelo’s homosexual attraction was Tommaso Cavalieri, and this can be easily proven by many of his poems, mainly No. 98: If capture and defeat must be my joy, It is no longer that, alone and naked, I remain prisoner of a knight-at-arms.24 However, Michelangelo decided to demonstrate his affection through some drawings. In one of them, Michelangelo recovered an old Greek myth – Ganymede – as a metaphor for his love towards Cavalieri. In it, Zeus is represented as an eagle responsible for the rape of the young Ganymede, a shepherd, who was then taken to Olympus because of his outstanding beauty and kept there as Zeus’ lover. It is noteworthy that when Michelangelo met Cavalieri he was already fifty-seven years old, while the latter was only twentythree.25 The reference is clear: Michelangelo felt like Zeus captivated by Cavalieri’s beauty. Assuming Michelangelo’s homosexuality, how can it be related to the Minerva Christ? Throughout his work, he clearly preferred to portray males nude. In the Sistine ceiling, the “ignudi” are everywhere. The most prominent and 22 23 24 Michelangelo Buonarroti. The Complete Poems of Michelangelo. (Trans. By John F. Nims. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1998), p. 18. Ibid., p. 22 Gilbert, op. cit., p. 96. Souza - 14 famous figure is Adam in the Creation of Man, fully nude. I believe Michelangelo wanted to show that male nudity is beautiful, and if Adam was already beautiful in the beginning of mankind, how much more attractive the New Adam, Christ, would have to be after the redemption from the Adamic sin. Again, the risen Savior can be depicted fully naked because in him there was no more sin. Therefore, the Minerva Christ is how Michelangelo wanted to see his Savior: a nude male in which there is no sin or punishment. The Minerva Christ was probably an attempt of the artist to identify some logic in the contradictory world he lived in: his sinful homosexual flesh fighting with the supreme purity in God. The Minerva Christ may have been his way of saying that there could be peace in his ego. Michelangelo’s homosexuality is also related to another aspect of his life that affected his work, a process that Freud called sublimation.26 Michelangelo worked so much that he considered his work as his wife in one of his writings.27 The above-mentioned latent homosexuality may have forced him to sublimate his libido, that is to transfer the power of his sexuality to other non-sexual activities such as his work, for example. The process of sublimation may be satisfactorily successful in other occupations: for example, celibate Catholic priests try to sublimate through prayers and other disciplinary exercises. An artist, however, ends up manifesting all his inner conflicts in his work, whether in paintings, sculptures or poems. That is intrinsic to the artistic process. Michelangelo may 25 26 Saslow. Ganymede in the Renaissance, op.cit., p.17. Sigmund Freud. Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. (Trans. and edited by James Strachey. New York: Norton, 1966), pp. 428-429. Souza - 15 have sublimated in his work, and the Minerva Christ could be seen as an icon of this process. In it, the artist showed his appreciation for the nude male form, unconsciously hiding behind the iconographical reference to the risen Savior. Other psychoanalytical aspects of Michelangelo’s personality are well described in some scholars’ work: the fact that his mother died when he was still very young,28 and the lack of a strong father figure.29 They all contribute to the explanation of a very disturbed ego. Nevertheless, I think that one of the most relevant psychoanalytical aspects of Michelangelo’s personality has yet to be further analyzed: why does he use nude male forms so many times in his work? Using the Minerva Christ example, I want to contribute to this subject. In one of his most celebrated books, The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud mentions some unusual dreams, among them the one in which one is naked in public. He pays attention only to the cases that cause discomfort to the dreamer. In other cases, dreaming of being naked in public may not be that problematic: This age of childhood, in which the sense of shame is unknown, seems a paradise when we look back upon it later, and paradise itself is nothing but the mass-phantasy of the childhood of the individual. This is why in paradise men are naked and unashamed, until the moment arrives when shame and fear awaken; expulsion follows, and sexual life and cultural development begin. Into this paradise dreams can take us back every night; we have already ventured the conjecture that the impressions of our earliest childhood (from the prehistoric period until about the end of the third year) crave reproduction for their own sake, perhaps without 27 28 29 Robert Linscott, as the Biographical Introduction to the translation of Creighton Gilbert, op. cit., p. xxxv: “I already have a wife who is too much for me; one who keeps me unceasingly struggling on. It is my art, and my works are my children.” Nathan Leites. Art and Life: Aspects of Michelangelo. (New York and London: New York University Press, 1986), pp. 1-7. Saslow. The Poetry of Michelangelo, p. 9. Souza - 16 further reference to their content, so that their repetition is a wishfulfilment. Dreams of nakedness, then, are exhibition-dreams.30 How does this explanation relate to Michelangelo and the Minerva Christ? I believe that the artist was willing to take us, through the nude in the course of his work, back to what Freud called “the paradise.” There is no evidence that Michelangelo had such dreams, but Freud himself pointed out that the artistic process is very similar to the dream process. Therefore, the Minerva Christ may be regarded as the unconscious manifestation of Michelangelo’s childish desire for a Christ free of shame. Perhaps this is true for all of the male nudes in his work. In this sense, the Minerva Christ may be regarded as an exhibition-dream. Freud also relates repression with the exhibition-dreams, and Michelangelo’s life is one full of repression, as already mentioned above, pertaining to his homosexuality: Furthermore, repression finds a place in the exhibition-dream. For the disagreeable sensation of the dream is, of course, the reaction on the part of the second psychic instance to the fact that the exhibitionistic scene which has been condemned by the censorship has nevertheless succeeded in presenting itself. The only way to avoid this sensation would be to refrain from reviving the scene.31 As in an exhibition-dream, the condemned scene of a beautiful nude adult male – Christ – has succeeded in presenting itself. Michelangelo was at ease, at least with this work, with the fact that he felt attraction for other men and that he could portray his Savior nude without moral restrictions. In summary, the three inner stimuli in Michelangelo, his homosexual drive, his sublimation and the artistic nude as exhibition-dreams contribute to the 30 Sigmund Freud. The Interpretation of Dreams. (4th ed. London: G. Allen & Unwin ; New York: Macmillan, 1915), chapter V. Souza - 17 consolidation of a complex personality. The Minerva Christ was a reification of such personal contradictions. Christ had to be nude in this work in order to be a symbolic representation, even unconscious in some of its elements, of the conflicting elements in permanent altercation in the genius life of Michelangelo. V. Conclusion Not long after its first public appearance, the Minerva Christ was mutilated. Christ’s genitalia were never again seen as originally planned by Michelangelo. Reproductions of the “covered” Christ were distributed throughout Europe. However, that nude Christ could have been an alternate reference to the troubled Catholic Church, which overreacted to the Protestant Reformation by abandoning its past history of tolerance in religious art manifestations. The Jesuits took over the orthodoxy of the church in the counter-reformation movement, and with them sexual repression became the norm. On the other side of the religious spectrum, the Protestants abandoned almost completely any form of religious art. In the middle of these two extremes was a nude Christ pointing to the release of sin and shame, to a higher degree of love, to a new possibility of union with God. Michelangelo’s psyche was the battlefield of all these conflicts. He suffered both conscious and unconscious influences, and they are all present in his work. I do not believe either in the Catholic Christ, or in the Protestant’s. However, I would like to have had the chance to worship the Minerva Christ together with Michelangelo in his inner “paradise.” 31 Ibid., chapter V. Souza - 18 Bibliography Agoston, Laura Camille. Michelangelo's Christ : the Dialectics of Sculpture. Harvard PhD Dissertation, 1993. Ames-Lewis, Frances and Bednarek, Anka (eds.). Decorum in Renaissance Narrative Art: Papers Delivered at the Annual Conference of the Association of Art Historians, London, April 1991. London: Department of History of Art, Birkbeck College, University of London, 1992. Blunt, Anthony. Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1600. London; New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. Clifton, James. The Body of Christ in the Art of Europe and New Spain, 11501800. Munich; New York: Prestel, 1997 Condivi, Ascanio. The Life of Michelangnolo Buonarroti. Trans. by Charles Holroyd. London: Duckworth, 1904 Freud, Sigmund. On Dreams. Trans. James Strachey. New York: Norton, 1963. _________. Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. Trans. and edited by James Strachey. New York: Norton, 1966. _________. Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood. Trans. by Alan Tyson. 1st American ed. New York : Norton, 1964 _________. The Interpretation of Dreams. 4th ed. London: G. Allen & Unwin ; New York: Macmillan, 1915. _________. The Ego and the Id. London: Hogarth Press, 1950. Hofstadter, Albert and Richard Kuhns (eds.). Philosophies of Art and Beauty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964. Leites, Nathan. Art and Life: Aspects of Michelangelo. New York and London: New York University Press, 1986. Liebert, Robert. “Michelangelo’s Mutilation of the Florence Pieta: a Psychoanalytical Inquiry”. The Art Bulletin 59 (1977). Reprinted in William Wallace, ed. Michelangelo: Selected Scholarship in English. 5 Vols. New York: Garland, 1995. Souza - 19 Michelangelo Buonarroti. The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation by James M. Saslow. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991. Michelangelo Buonarroti. Complete Poems and Selected Letters of Michelangelo; translated, with foreword and notes, by Creighton Gilbert ; edited, with biographical introduction, by Robert N. Linscott. 3rd ed. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1980. Michelangelo Buonarroti. The Complete Poems of Michelangelo. Trans. By John F. Nims. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1998. Panofsky-Soergel, Gerda. Michelangelos "Christus" und sein romischer Auftraggeber. Worms: Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1991. Roberts, Helene (ed.). Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography : Themes Depicted in Works of Art. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1998. Saslow, James M. Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in Art and Society. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986. Steinberg, Leo. The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. Turner, Jane (ed.). The Dictionary of Art. New York: Grove's Dictionaries, 1996. Vasari, Giorgio. Vasari's Lives of the Artists: the Classic Biographical Work on the Greatest Architects, Sculptors and Painters of the Italian Renaissance, abridged and edited with commentary by Betty Burroughs. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1946. Wallace, William E. Michelangelo and his Drawings. By Michael Hirst. New Haven, London, 1988. Weinstein, Donald. Savonarola and Florence; Prophecy and Patriotism in the Renaissance. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1970. Souza - 20 Annex I Figure 1 Figure 2 Souza - 21