EIN NLINE

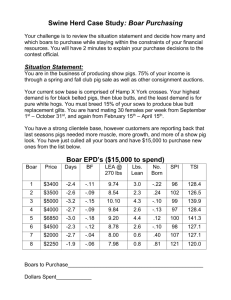

advertisement