Teaching Introductory Chemistry with a Molecular and Global

Teaching Introductory Chemistry with a

Molecular and Global Perspective:

The Union of Concepts and Context

CSR Workshop on Undergraduate

Chemistry Education

22 May 2013

Jim Anderson

Harvard University

The Question is: How do we develop an innovative university level strategy leading to the proactive engagement of science and technology in the core objectives of the nation’s future? And why?

1

Illiteracy of university graduates in the physical sciences

Physical sciences hold key to solving problems of immense concern

Research has demonstrated how students learn (?) chemistry and physics

Needed:

New Strategic

Approach for

Introduction

Chemistry

Central role and responsibility of physical sciences in societal objectives

Universities have a major responsibility to prepare their graduates

Introductory courses taught without a compelling context exclude rather than include

Large departure of undergraduates from the physical sciences

2

P

HYSICAL

S

CIENCES

11:

Frontiers and Foundations of Modern

Chemistry: A Molecular and

Global Perspective

Revolutionary developments in the union of chemistry and physics hold the key to solving unprecedented problems at the intersection of science, technology, and an array of rapidly emerging global scale challenges. In particular concepts central to energy and its transformations, thermodynamics, energy, entropy and free energy, quantum mechanics, atomic structure, molecular bonding, kinetics, catalysis, equilibria and acid-base reactions, and nuclear chemistry are presented with emphasis on the context of (1) world energy sources, forecasts and constraints, (2) the science and technology linking energy and climate,

(3) modern materials and technology.

Instructors:

James G. Anderson and

Gregory C. Tucci

3

What Drives the Strategy of PS 11?

•

The University Has Specific

Responsibilities to Its Students and to the Nation.

•

Revolutionary developments at the union of chemistry and physics hold the key to solving unprecedented problems at the intersection of science, technology, and an array of rapidly emerging global scale challenges.

4

Reconsideration of the strategy of university science curricula is founded on the premise that it is the responsibility of universities to look forward in time:

2010 2015 2020 2025

1. Decisions on what current university graduates face maps directly back to what they take in their freshman year.

2. If courses taken in the freshman year fail to deliver objectives, it is difficult to recover—particularly in the sciences.

5

All university graduates today, independent of chosen concentration, face coming to terms with a number of questions:

1.

What technical forces are shaping the modern world?

4.

2.

Which public policy strategies are founded on sound scientific and technological understanding and which are not?

Where are the frontiers of innovation and what implications do those advances hold for professional endeavors ...

3.

not just in technology, but also in international economics, government, ethics, public health, law and education.

6

Yet a growing compendium of research has shown that university graduates in the United States are, to a remarkable degree, lacking both fundamental knowledge of the physical sciences and the associated judgment with respect to consequences for society and for the nation’s future.

7

Yet a growing compendium of research has shown that university graduates in the

United States are, to a remarkable degree, lacking both fundamental knowledge of the physical sciences and the associated judgment with respect to consequences for society and for the nation’s future.

Research has shown:

1. Significant contributor to this lack of an effective scientific foundation is that introductory chemistry & physics are taught as isolated subjects.

2. Courses taught as isolated course material, without a larger and compelling context, create an exclusive rather than inclusive message leading to irreversible elimination.

8

P

HYSICAL

S

CIENCES

11:

Frontiers and Foundations of Modern

Chemistry: A Molecular and

Global Perspective

Revolutionary developments in the union of chemistry and physics hold the key to solving unprecedented problems at the intersection of science, technology, and an array of rapidly emerging global scale challenges. In particular concepts central to energy and its transformations, thermodynamics, energy, entropy and free energy, quantum mechanics, atomic structure, molecular bonding, kinetics, catalysis, equilibria and acid-base reactions, and nuclear chemistry are presented with emphasis on the context of (1) world energy sources, forecasts and constraints, (2) the science and technology linking energy and climate,

(3) modern materials and technology.

What are those responsibilities :

• to look forward in time to judge challenges emerging 5 years, a decade, two decades in the future;

• to establish a state-ofthe-art science/ technology curriculum to proactively address those emerging challenges; and

• to link those developments into the structure and function of the global enterprise.

9

“If I learned anything in my forty one years of teaching, it is that the best way to transmit knowledge and stimulate thought is to teach from the top down. Begin by posing large problems, questions and concepts of the highest significance and then peel off layers of causation as currently understood. Do not teach from the bottom up.”

— E.O. Wilson

10

11

•

This increasingly powerful union of science and society places the physical sciences in a position of direct responsibility.

12

•

Why does this come back to roost on the physical sciences?

•

Because (1) technology leadership, (2) advances in human health, (3) national security, (4) international negotiations, (5) world energy sources, forecasts and constraints, (6) the science and technology linking energy and climate, and (7) modern materials....

13

•

....

requires an understanding of energy and its transformations, thermodynamics, entropy and free energy, equlibria, acid-base reactions, electrochemistry, quantum mechanics, atomic structure, molecular bonding, kinetics, catalysis, materials and nuclear chemistry.

14

What is the Dynamic of Higher Education in the US?

15

•

While there are significant differences between universities, there is a general pattern common to all: attrition from the sciences during and following the freshman year.

•

Eyeballed from the perspective of graduate school or medical school entrance, the situation is at least tolerable.

16

•

National security, competitive economic considerations and human health should dominate public policy debates. But instead, public policy debates are dominated in large part by a lack of essential information and perspective that should be an integral part of a modern university education.

17

18

Time to Melt: 1980

→

2012

32 Years

1.1

×

10 15 kWh

=

3.4

×

10 13 kWh/yr

32 years

Solar Forcing of Climate: 1 × 10 18 kWh/yr

Circulating Energy Between Surface

And Clouds, Water Vapor, CO

2

, Etc.:

1.7 × 10 18 kWh/yr

17

×

10 17

3.4

×

10 13

kWh/yr kWh/yr

=

4.3

×

10 4 q = ( ∆ H fusion

)(mass ice)

∆ Volume = 16 × 10 3 km 3 – 3 × 10 3 km

= 13 × 10 3 km 3

= 13 × 10 12 m 3 = 1.3 × 10 13 m 3

∆ H fusion

= 3.3 × 10 2 kJ/kg ice

Ice is 9.2 × 10 2 kg/m 3

∆ mass ice = (1.3 × 10 13 m 3 ) 1 × 10 3 kg/m 3

= 1.2 × 10 16 kg ice q = (3.3 × 10 2 kJ/kg) 1.2 × 10 16 kg

= 4.0 × 10 18 kJ = 4.0 × 10 21 J

= 1.1 × 10 15 kWh

19

How does energy flow within the climate system, and what is the magnitude of that energy flow?

Energy flow per year

Sun

0.5 × 10 18 kWh reflected

1.0 × 10 18 kWh emitted to space

1.5 × 10 18 kWh

Water Vapor

Carbon Dioxide

Clouds

Earth

1.0 × 10 18 kWh into climate system

Ocean

Water Vapor

Carbon Dioxide

Clouds

1.7 × 10 18 kWh cycling within climate system

Ice

20

•

In the US we need

95% of university graduates who are scientifically and technical literate.

Without the basic scientific foundation, it becomes virtually impossible to make the required connections to proactively engage in future decisions.

21

Current Strategy in

Introductory Chemistry:

•

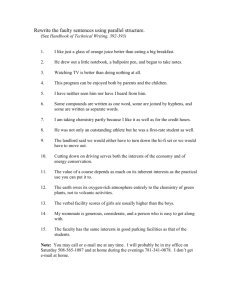

Present lectures and text material that covers the basic formalism and theory

•

Followed by problem sets, exams, etc.

22

•

Solid evidence has shown that there are two basic failures with the “formalism first” approach to teaching. First, it results in

“disembodied knowledge.”

•

Students cannot attach the knowledge to a context or their past experience, and so it is largely meaningless symbols and facts to memorize.

•

Carl has shown that knowledge obtained this way is filed away in the brain in a separate compartment and building links to that compartment after the fact is much harder and less effective than if it had been filed correctly from the start.

23

P

HYSICAL

S

CIENCES

11:

Frontiers and Foundations of Modern

Chemistry: A Molecular and

Global Perspective

Revolutionary developments in the union of chemistry and physics hold the key to solving unprecedented problems at the intersection of science, technology, and an array of rapidly emerging global scale challenges. In particular concepts central to energy and its transformations, thermodynamics, energy, entropy and free energy, quantum mechanics, atomic structure, molecular bonding, kinetics, catalysis, equilibria and acid-base reactions, and nuclear chemistry are presented with emphasis on the context of (1) world energy sources, forecasts and constraints, (2) the science and technology linking energy and climate,

(3) modern materials and technology.

•

The question is, how do we develop a strategy that weaves a modern perspective on the proactive role of science and technology into a university curriculum?

24

Course Objectives

Linking Concepts with Context

CONTEXT

Glogal Energy

Structure

Consequences:

Structure of the Climate

Energy Options

Energy Technology

Carbon Footprints

Climate Engineering

Energy:

Scienti fi c

Foundations

Thermodynamics

Chemical

Equilibria

Electrochemistry

CONCEPTS

Electricity &

Magnetism

Induction

Quantum

Mechanics

Molecular

Bonding

Kinetics

Photochemistry

Nuclear

99 th percentile

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

ism emerges, there is a proactive engagement of the concepts with the larger contextual vision. Th is provides an individual seeking to understand a scienti fi c principle with a much more robust and useful knowledge base.

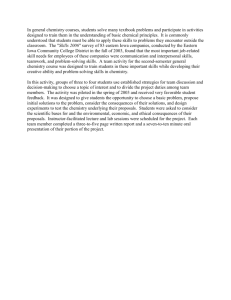

So it is the union of these two perspectives: (1) the critical role played by the physical sciences in the solution of unprecedented societal need and objectives, and (2) compelling evidence for how scienti fi c principles and quantitative reasoning skills are mastered at the university level that establishes the structure of this text. Given that the objective of the text is to (1) establish the imperative de fi ning the central role that the principles of chemistry and physics play in the unfolding global challenges, (2) develop the core concepts of, among others: energy and energy transformations, thermodynamics, chemical equlibria, acid/base and redox reactivity, electrochemistry, quantum mechanics, molecular bonding, kinetics, catalysis, materials, nuclear, and (3) establish the direct link between those core concepts and the larger global context, the structure of the text consists of three primary elements. Each chapter opens with a “Framework” section that establishes the larger context de fi ning why the scienti fi c concepts treated in that chapter are critically important to science and technology’s role in addressing rapidly emerging challenges at the global scale. Th e chapter “Core” that addresses the quantitative concepts central to the modern physical sciences follows that Framework section. Th e third element in the chapter structure are the “Case Studies” that link the concepts in the chapter Core to the larger global context. Th ose Case

Studies fall into three categories: (a) Case Studies designed to build quantitative reasoning skills, (b) Case Studies designed to build a technology backbone, and (3) Case Studies designed to build a global energy backbone to supply the dramatic expansion in the need for primary energy generation

Th us, as the adjoining fi gure illustrates in graphical form, the Case Studies link the central concepts in contemporary physical science and technology into the global concepts of human health, technology leadership, economic choices, national security, energy production and distribution, climate consequences of energy production choices, and international negotiations to pick a few examples .

Th is development of the context and the concepts together in the structure of the text does not imply, however, that these changes are done at the expense of rigor in the development of scienti fi c principles. Th e depth of the development of both the context and the scienti fi c principles are gauged to provide the student with the preparation needed to compete successfully today and in the future in the international scienti fi c and societal arena.

International Negotiations:

Technology Leadership,

Arms Control

BUILDING

A TECHNOLOGY

BACKBONE

CASE

STUDIES

Innovative New Materials:

Nano Structures, Self Assembly,

Solar Cells, Electronics

Energy Production, Storage and

Distribution

– Concepts –

Human Health: Molecular and

Cellular Level Imaging, Low Cost

Disease Detection, Clean Water

Feedbacks in the Climate Structure:

Thermodynamics, the First Law &

Irreversibility

BUILDING A

GLOBAL ENERGY

BACKBONE

– Context –

CA

SE

STUDIES

BUILDING

QUANTITATIVE

REASONING

Technology Leadership: Electronics,

Electric Automobiles, Health Systems and Software

33 v

99 th percentile

Physical Sciences 11

Global Calculations Clinic

3 May 2013

10AM Hall B

34

Some Questions That All University

Graduates Should Know the Answer to:

1.What is the ratio of power received from the Sun to the power consumed by the human endeavor? What is the amount spent on energy extraction and distribution each year world-wide?

2.How do you calculate global energy demand? The increase in global energy demand?

3.To meet that demand do we need to build a 600MW power plant every month for the next 40 years? Every week?

Everyday? Two every day?

4.When we trace the flow of energy from its production to its end use, why is 65% lost to waste? What controls that?

35

36

Some (More) Questions That All

University Graduates Should Know the

Answer to:

5. How much does the nation spend on petroleum imports each year? What fraction is from the Western Hemisphere, what fraction from the Middle East?

6. How do you calculate energy to propel a gasoline automobile 100km? An electric car 100km? How much does the nation spend on gasoline each year? If the fleet was electric how much would the nation spend? By what fraction would that increase electricity demand?

7. Is it more efficient to heat a home by burning natural gas in the home or burn it in a power plant and then employing a heat pump in the house using that electricity?

37

Some (More) Questions That All

University Graduates Should Know the

Answer to:

8. Given that the US uses 3 TW of power, what fraction of the state of Arizona is required to generate 1 TW from concentrated solar thermal? What fraction of the land area of the Middle West is required to generate a second TW from wind power? How much does each cost? How much does it cost to install a national grid?

9. We have lost 50% of the permanent floating ice on the

Arctic Ocean in the past 30 years. What controls the rate of removal of the second half? When was the Arctic last without permanent floating ice? How does the amount of energy required to melt that amount of ice each year compare to the amount of energy circulating between the Earth’s surface and the water vapor, clouds and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere?

38

PUBLIC POLICY

&

GOVERNMENT

ECONOMICS

PHYSICS

CHEMISTRY

39

ECONOMICS

PUBLIC POLICY

&

GOVERNMENT

SCIENCES

40

PS 11 Metrics?

•

Spring 2012: First Lecture - 25 Students;

Second Lecture - 50 Students; Third

Lecture - 100 Students; Fourth Lecture

-125 Students

•

Spring 2013: ~ 300 Students

41

• END

42

42