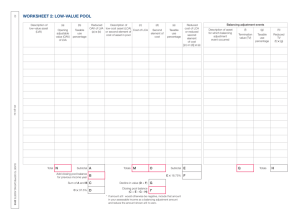

Guide to depreciating assets 2013

advertisement