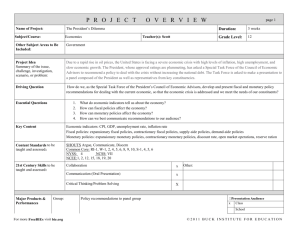

182 CHAPTER 12 INTERNATIONAL LINKAGES Chapter Outline

advertisement

CHAPTER 12

INTERNATIONAL LINKAGES

Chapter Outline:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

The balance of payments

Fixed exchange rates

Flexible exchange rates

Intervention

The Euro

Purchasing power parity

Repercussion effects

The IS-LM model and foreign trade

Capital mobility

External and internal balance

The Mundell-Fleming model

The effects of fiscal and monetary policy

The re-unification of Germany

Beggar-thy-neighbor policies

Changes from the Previous Edition:

The chapter has been updated but otherwise mostly left intact. More emphasis is given to the

dollar-yen rather than the dollar-DM exchange rate, because of the introduction of a common currency

(the Euro) in the European Union. Box 12-1 previously dealt with the criteria of the 1991 Maastricht

Treaty but now deals with issues surrounding the Euro.

Introduction to the Material:

Chapter 12 serves to introduce the key linkages between open economies, that is, countries that

trade with others. The closed economy presented thus far is obviously not a very good representation of

the U.S. economy as an integral part of the global economic environment. Therefore the IS-LM model of

income determination derived in Chapters 10 and 11 is expanded here to include international aspects. It

considers fixed and flexible exchange rates, but continues to assume that the domestic price level is fixed

and that whatever level of output is demanded will always be supplied.

The increased globalization of economic activity makes it mandatory that students understand the

important aspects of international trade and finance and the ways economic influences from abroad can

affect the U.S. economy and vice versa. International trade deals with issues related to the export of

domestically produced goods and the import of goods produced abroad. International finance deals with

the capital flows that occur as portfolio managers around the world shift their holdings of domestic and

foreign assets (bonds issued by domestic and foreign governments or corporations). The actions of

international investors (who seek the highest yield on their assets) and foreign governments (who respond

182

to domestic policy actions) affect exchange rates, domestic income, and the ability of governments to

conduct independent domestic stabilization policies.

The balance of payments as the record of transactions between one country and the rest of the

world is introduced first. The two main accounts in the balance of payments are the current account

(which records trade in goods, services, and transfer payments) and the capital account (which records the

trade in assets). The overall balance of payments surplus or deficit is the sum of the current and capital

account surpluses or deficits.

The different ways in which central banks provide the means to finance balance of payment

surpluses or deficits are examined under a fixed and a floating exchange rate system. A fixed exchange

rate system works very much like an agricultural price support system, as central banks stand ready to buy

or sell currencies at a fixed price. Under such a system, the central bank of a country that runs persistent

balance of payment deficits has to buy its own currency; however, it cannot do so continuously, since it

will eventually run out of foreign currency reserves. Therefore it may be forced to devalue its currency.

Under a flexible exchange rate system, central banks generally allow exchange rates to be determined

solely by the supply and demand for foreign currency. However, we seldom observe such clean floating

and instead central banks often practice managed (or dirty) floating, that is, they intervene to influence

exchange rates by buying or selling foreign currencies. Reasons for such actions are discussed in Chapter

21, which covers international aspects in more detail.

Box 12-1 looks at issues surrounding the introduction of a common currency, the Euro, in the

countries of the European Union. This new currency was introduced in 1999, and by the year 2002, the

new notes and coins will have replaced the different national currencies such as the franc, lira, or mark. A

key issue in this monetary conversion was the criteria that each member country had to fulfill, as specified

in the 1991 Maastricht Treaty. Even now, however, questions remain about the benefits of giving up

national currencies and the exchange rate as a policy tool in exchange for increased political integration.

The problems that arose after the re-unification of Germany are discussed in Box 12-2. The high

interest rates in Germany, caused by the fiscal expansion needed to improve the infrastructure in the new

eastern states, presented other European countries with the unpleasant choice of either allowing their

interest rates to also increase or devaluating their currencies within the European monetary system. Both

of these boxes deserve attention since they discuss important events of the last decade.

A country's competitiveness in foreign trade is measured by the real exchange rate, that is, the

ratio of foreign to domestic prices measured in the same currency. Two currencies are at purchasing

power parity (PPP) when one unit of the domestic currency can buy the same basket of goods in the home

country and in a foreign country. While the movement towards purchasing power parity tends to be very

slow, market forces generally prevent the exchange rate from moving too far or remaining indefinitely

away from this purchasing power parity.

In an open economy, part of domestic income will be spent on imports rather than

domestic products. To incorporate foreign trade into the IS-LM framework derived in Chapter 10, net

exports (NX) as the difference between exports (X) and imports (Q) is re-defined as

NX = X(Yf,R) - Q(Y,R).

This implies that the open economy IS-curve now is of the form:

Y = A(Y,i) + NX(Y,Yf,R)

In other words, domestic spending (A) depends on domestic income (Y) and the interest rate (i), while net

exports (NX) depend on domestic income (Y), foreign income (Yf) and the real exchange rate (R). Since a

fraction of each additional dollar of domestic income (the marginal propensity to import) is spent on

183

foreign goods, the expenditure multiplier is smaller in an open economy model, implying that the open

economy IS-curve is steeper than the closed economy IS-curve.

We can see that an increase in foreign income will raise the demand for domestic products and

this will raise domestic income and interest rates. In a global economy, if our government implements

expansionary fiscal policy, the effect will not only stimulate the domestic economy but also lead to an

increase in foreign income. In turn, the increase in economic activity in other countries may add to our

domestic income expansion. Such repercussion effects may also arise in response to changes in exchange

rates. A depreciation in our exchange rate, for example, increases our competitiveness in world markets.

Therefore domestic income is increased while foreign income is reduced.

The high degree of integration among world capital markets implies that interest rates in one

country cannot get too far out of line with the interest rates in other countries without substantial capital

flows taking place. Such capital mobility has important implications for the effectiveness of monetary and

fiscal stabilization policy. If capital is assumed to be perfectly mobile, then investors in one country can

trade assets with investors in any other country without restrictions, that is, at low transaction costs and in

unlimited amounts in search of the highest yield or the lowest borrowing costs. The balance of payments

surplus (BP) is equal to the trade surplus (NX), which depends on domestic income (Y), foreign income

(Yf), and the exchange rate (R), plus the capital account surplus (CF), which depends on the differential

between the domestic interest rate (i) and the foreign interest rate (if). This is shown in Equation (8):

BP = NX(Y, Yf ,R) + CF(i - if)

The implications of perfect capital mobility are examined under fixed and flexible exchange rate

systems. Under a system of fixed exchange rates, expansionary fiscal policy is automatically reinforced

by monetary policy, since higher domestic interest rates and the resulting capital inflow force the central

bank to increase the money stock to maintain the fixed exchange rate. Monetary policy, on the other hand,

is powerless in such a situation. The inflow of capital simply forces the central bank to reverse its initial

policy action. By contrast, under a flexible exchange rate system fiscal policy is ineffective while

monetary policy is highly effective. Expansionary fiscal policy results in higher domestic interest rates, a

capital inflow, and an appreciation of the domestic currency. This results in the crowding out of net

exports. Expansionary monetary policy, on the other hand, leads to a depreciation of the domestic

currency, increased exports and therefore a higher level of domestic output. Such a policy is known as a

beggar-thy-neighbor policy, since an increase in domestic employment has been created at the expense of

foreign countries that might experience higher levels of unemployment.

Expansionary monetary policy can serve to improve the domestic unemployment problem but it

will worsen the balance of payments. This can present a policy dilemma between the goals of internal and

external balance. Internal balance exists when the economy is at the full-employment level of output and

external balance exists when there is a balance of payments equilibrium. Since capital flows tend to be

interest sensitive, a country can finance a trade deficit by raising interest rates. This means that an

appropriate fiscal/monetary policy mix might be found that would establish internal and external balance

simultaneously.

The graphical analysis that extends the IS-LM model to the open economy under the assumption

of perfect capital mobility is called the Mundell-Fleming model. This model is used to explore the effects

of fiscal and monetary policies under both fixed and flexible exchange rate systems, and Robert Mundell

was rewarded with the Nobel price in economics for his important work on this subject. While the model

was developed well before flexible exchange rates came into operation, it still provides good insights into

the way policies work in a world of high capital mobility.

184

Suggestions for Lecturing:

Students tend to be most interested in the discussion of current international problems, such as the

creation of a new European currency, factors that can affect the value of the U.S. dollar, or the potential

for an international debt crisis. To capture students' interest, instructors should relate the theoretical

framework discussed in this chapter to real world issues as often as possible.

To introduce the difference between the current account and the capital account and to stimulate

discussion among students, instructors can pose the following two questions:

•

•

If a country runs a large trade deficit, what is likely to happen to the value of the country's

currency? The obvious answer is that, all else being equal, the value of the domestic currency

should decrease.

U.S. trade deficits increased rapidly in the early to mid 1980s, so what should have happened to

the U.S. dollar in that time period? Students most likely will answer that the value of the U.S.

dollar should have decreased. They may be astonished to learn that in the first half of the 1980s

the value of the U.S. dollar actually increased substantially.

How can we understand this seemingly illogical occurrence? The explanation lies in the large

inflow of foreign funds, attracted by high U.S. interest rates. These high interest rates were the result of

the expansionary fiscal/restrictive monetary policy mix of the early Reagan years, which led to an

increase in the demand for U.S. dollars and a sharp increase in the value of the dollar. This currency

appreciation made domestic products less competitive on world markets, causing an increase in the U.S.

trade deficit. This situation provides another good example of how difficult it is to distinguish between

cause and effect in macroeconomics.

Instructors may have already at least briefly discussed the relationship between budget deficits

(BD) and trade deficits (TD) when they discussed the national income accounting identities in Chapter 2

along with the equation

S - I = (G + TR - TA) + NX.

By changing this equation slightly we can derive

S - I = - (TA - G - TR) - (-NX) ==> S - I = BD - TD,

that is, the difference between private domestic saving and private domestic investment is equal to the

difference between the budget deficit and the trade deficit. In other words, if domestic saving is not

sufficient to finance domestic investment and the budget deficit, then funds have to be borrowed from

abroad. But the resulting inflow of capital will lead to an appreciation of the currency that will, in turn,

result in a trade imbalance. If this has already been done, then instructors can build on students'

knowledge by discussing capital flows as a result of interest rate differentials and their impact on the

effectiveness of fiscal and monetary stabilization policies under a system of flexible exchange rates.

Instructors may also want to point out that, even though the large U.S. federal budget deficits of the 1980s

have turned into budget surpluses by the late 1990s, the U.S. trade imbalance has by no means improved.

While some instructors may want to spend some time on the complex issues surrounding the trade

imbalance at this point, others may want to wait until a more detailed discussion is possible in Chapter 21.

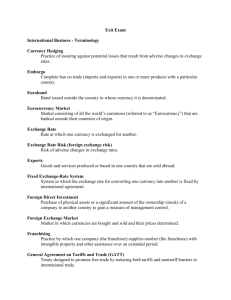

Since the terminology in this chapter can be somewhat confusing, it is important to note the

difference between currency depreciation (appreciation) and currency devaluation (revaluation). Under a

system of floating exchange rates a currency depreciates (appreciates) when it becomes less (more)

185

expensive in relation to foreign currencies. Under a system of fixed exchange rates currency devaluation

(revaluation) takes place when the price at which foreign currencies can be bought is increased (decreased)

by official government action.

Since most students are at least somewhat familiar with the events in Europe in the 1990s, the

material in Boxes 12-1 and 12-2 also provides a good basis for a lively classroom discussion. The

material relating to the German re-unification can be used to show parallels with the policy mix employed

in the U.S. in the early 1980s and to demonstrate why it is hard to maintain fixed exchange rates when the

countries involved choose to pursue different policy objectives. Some instructors may have already

mentioned these parallels in Chapter 11, as they make a good connection between the two chapters.

The discussion of the issues surrounding the introduction of the Euro as the common currency for

the countries of the European Union will definitely spark students' interest. Many may have traveled in

Europe already and are therefore familiar with the different national currencies. They may have realized

that, starting in the late 1990s, menu prices in some restaurants were already listed in Euros, even though

the meal still had to be paid in the national currency, since the Euro was not yet officially available for

purchasing items. Special attention should be given to the benefits and drawbacks for a country that gives

up its national currency (and the exchange rate as a policy tool) in exchange for increased political and

economic integration.

Since the material in this chapter is a very logical extension of the IS-LM framework from the

two previous chapters, students with good graphical skills should be able to handle it without much

trouble. But other students will undoubtedly have some difficulty with the material in this chapter,

especially with the formal analysis required by the extension of the IS-LM framework to the open

economy (the so-called Mundell-Fleming model). As understanding of the material in subsequent

chapters will not suffer greatly as a result, instructors may choose to discuss exchange rate determination

and the effects of international capital flows on the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy without the

formal treatment in an IS-LM framework. Time constraints and the preference of individual instructors

should determine how much material in this chapter is covered. Whatever approach instructors choose to

take, it is very important that students get a sense of the impact that the increased internationalization of

the world economy has had on domestic economic stabilization policy. This implies a familiarity with

exchange rate determination in a freely floating exchange rate system and with the implications of capital

mobility for fiscal and monetary policy.

Instructors should make sure to point out that the purchasing power parity relationship suggests

that, in the long run, exchange rate movements in a freely floating exchange rate system mainly reflect

differentials in the inflation rate between countries. In the short run, however, real disturbances can affect

the terms of trade and therefore the exchange rate. Exchange rate movements in the short run often are

explained by interest rate differentials between countries.

The policy dilemma between the goals of external and internal balance also deserves some

attention. External balance exists when the balance of payments is in equilibrium and internal balance

exists when output is at the full-employment level. Expansionary monetary policy, for example, leads to a

depreciation of the domestic currency, increased exports, and therefore a higher level of domestic output,

that is, a reduction in unemployment. Such a beggar-thy-neighbor policy increases domestic employment

at the expense of foreign countries. It also results in a balance of payments deficit. Since capital flows

tend to be interest sensitive, a country has to correct the imbalance by raising domestic interest rates. With

an appropriate fiscal/monetary policy mix a government may be able to establish internal and external

balance simultaneously.

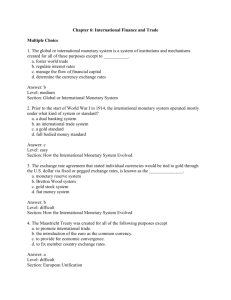

The effects of fiscal and monetary policy under perfect capital mobility for both a fixed and a

flexible exchange rate system are summarized in Table 12-6. This table is probably most useful to those

instructors who choose to deal with the graphical analysis presented in this chapter.

186

Additional Readings:

Batten, D. and Ott, M., "Five Common Myths About Floating Exchange Rates," Review, FRB of St. Louis,

November, 1983.

Chrystal, Alec K., "A Guide to Foreign Exchange Markets," Review, FRB of St. Louis, March, 1984.

Duisenberg, Willem, “Economic and Monetary Union in Europe—the Challenges Ahead,” in New

Challenges for Monetary Policy, FRB of Kansas City, 1999.

The Economist, “The Debate That Will Not Die,” June 17, 2000.

The Economist, “The Euro’s Agony, Europe’s Opportunity,” April 29, 2000.

The Economist, “Figures to Fret About,” July 11, 1998.

The Economist, "School Brief--Why Currencies Overshoot," December 1, 1990.

Engel, C. and Rogers, J., "How Wide is the Border?" American Economic Review, December, 1996.

Frankel, J. and Rose, A., "A Panel Project on Purchasing Power Parity," Journal of International

Economics, February, 1996.

Frankel, J. and Mussa, M., "Asset Markets, Exchange Rates and the Balance of Payments," in Jones, R.

and Kenen, P. (eds.), Handbook of International Economics, NorthHolland, Amsterdam, 1985.

Frieden, Jeffry, “The Euro: Who Wins? Who Loses?” Foreign Policy, Fall, 1998.

Friedman, Milton, "The Case for Flexible Exchange Rates," in Essays in Positive Economics, University

of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1953.

Gros, D. and Thygesen, N. European Monetary Integration: From the European Monetary System to

Economic and Monetary Union, Addison-Wesley-Longman, New York, 1998.

Higgins, Bryon, "Was the ERM Crisis Inevitable?" Economic Review, FRB of Kansas City, Fourth

Quarter, 1993.

IMF Survey, "German Unification Requires Rapid Adjustment in the East," January 21, 1991.

Rogoff, Kenneth, "The Purchasing Power Parity Puzzle," Journal of Economic Literature, June, 1996.

Schmitt, J. and Mishel, L., “The United States Is Not Ahead in Everything That Matters,” Challenge,

November/December, 1998.

Sheridan, Jerome, “The Consequences of the Euro,” Challenge, January/February, 1999.

Solomon, Robert, “The Birth of the Euro,” The Brookings Review, Summer, 1999.

Throop, Adrian, "Fiscal Policy and Exchange Rates," Weekly Letter, FRB of San Francisco,

September 15, 1989.

Throop, Adrian, "Monetary Policy and Exchange Rates," Weekly Letter, FRB of San Francisco,

September 22, 1989.

Learning Objectives:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Students should be able to distinguish between the capital account and the current account.

Students should be able to distinguish between fixed, freely floating and managed (or dirty) floating

exchange rate systems.

Students should be familiar with the issues related to the Euro.

Students should know the factors that may lead to a change in the value of a country's currency.

Students should know the difference between a currency appreciation (depreciation) and a currency

revaluation (devaluation).

Students should be familiar with the concept of purchasing power parity.

Students should be aware of the importance of repercussion effects.

187

•

•

•

•

Students should be able to use the IS-LM model to show the effects of fiscal and monetary policy in

an open economy.

Students should be able to distinguish between an external balance and an internal balance.

Students should be familiar with the Mundell-Fleming model.

Students should be familiar with the issues related to the German re-unification.

Solutions to the Problems in the Textbook:

Conceptual Problems:

1.

A country with a balance-of-payments deficit has made more payments of currency to foreigners than

it receives and the country’s central bank generally provides the needed funds. If the central bank

refuses to do so, the country will experience a decrease in money supply, which will eventually lead

to a recession. As domestic income goes down, less will be spent on imports. Since the domestic price

level is likely to decrease in a recession, people from abroad will begin to demand more of the

country’s goods and exports will increase, ultimately leading to a new equilibrium in the external

balance.

2.a. A decrease in exports leads to a decrease in income and to a trade deficit. This situation cannot be

remedied with standard demand-side stabilization policy. The most appropriate policy response

would be protectionist measures (tariffs) or export subsidies combined with expansionary fiscal

policy.

2.b. A decrease in private domestic saving and a corresponding increase in the level of domestic

consumption will lead to an increase in national income. If only more domestic goods are demanded,

then no trade deficit will occur. But if consumers also demand more foreign goods, then a trade

deficit will occur. In either case, a cut in government spending is the most appropriate policy response.

2.c. An increase in government spending will increase national income and lead to a trade deficit. A

subsequent cut in spending is the most appropriate policy response.

2.d. A shift from imports to domestic goods will increase national income and lead to a trade surplus. This

situation cannot be remedied with standard demand-side stabilization policy. A cut in government

spending combined with lower tariffs is the most appropriate policy response.

2.e. A reduction in imports combined with a corresponding increase in saving will lead to a trade surplus

but no change in national income. A cut in income taxes combined with lower tariffs is the most

appropriate policy response.

3. Expansionary monetary policy lowers the interest rate, which stimulates the level of investment

spending and therefore aggregate demand. If there is perfect capital mobility, lower interest rates will

also lead to a capital outflow, which will result in a depreciation of the currency. Export goods will be

cheaper for foreigners, so more of them will be demanded. The increase in net exports will lead to an

even higher level of aggregate demand and therefore national income.

188

4.a. An increase in the dollar/pound exchange rate means that now more U.S. dollars are required to buy

one British pound. Therefore the U.S. dollar has depreciated in value.

4.b. A depreciation in the value of the U.S. dollar is equivalent to an appreciation of the British pound.

5. Under a system of fixed exchange rates, a devaluation of the currency takes place when the price at

which foreign currencies can be bought is increased by official government action. Under a system of

floating exchange rates, currency depreciation takes place when there is an excess supply of the

domestic currency on foreign exchange markets, therefore making it less expensive to buy domestic

currency in terms of foreign currencies.

6. The purchasing power parity theory suggests that exchange rate movements mainly reflect the

differentials in national inflation rates. This theory holds up reasonably well in the long run,

especially when inflation rates are high and caused by changes in monetary growth. However, in the

short run, even a monetary disturbance will affect foreign competitiveness, since exchange rates move

faster than the price level. Similarly, when a real disturbance occurs, the purchasing power parity

relationship will no longer hold, since the adjustment will affect the terms of trade. Examples of such

real disturbances are changes in technology, shifts in export demand, or shifts in potential output in

different countries.

7. Economists work with simplified models that are designed to represent the real world as much as

possible. Any assumptions made should approximate reality. Economists do care whether the

purchasing power parity relationship holds, since many models in international economics assume

that it does, and it seems intuitively correct.

8.

A country is in external balance when the balance of payments is neither in surplus nor in deficit.

Under these circumstances, central bank reserves remain stable. A country is in internal balance when

output is at the full-employment level. Optimally, a country wants to be in external and internal

balance simultaneously, but often there is a conflict between these two policy goals. In such a case,

policy makers have to decide which goal has priority at the time.

9.

In the Mundell-Fleming model with fixed exchange rates and perfect capital mobility, fiscal policy is

more effective than monetary policy. As a matter of fact, monetary policy is totally ineffective in this

case. Monetary policy affects interest rates, which causes a flow of capital that affects exchange rates.

In order to keep exchange rates fixed, the monetary policy has to be reversed immediately.

10.a. Expansionary monetary policy lowers domestic interest rates. This not only stimulates the level of

domestic investment spending but also results in an outflow of funds that will result in a depreciation

of the currency. This makes domestic goods more competitive on world markets and therefore

stimulates aggregate demand even more by increasing net exports.

189

10.b. The reaction of other countries depends very much on the performance of their economies (their

position in the business cycle) at the time. Policy makers in a country that is in a recession will be

unhappy since the beggar-thy-neighbor policy will lead to more unemployment. Policy makers in a

country that is in a boom may actually welcome a appreciation of their currency. The reason is that

the increase in their public’s demand for imported goods may reduce some of the inflationary

pressure that they may experience in a boom.

10.c. The policy described in this problem is always a beggar-thy-neighbor policy. However, as the answer

to 10.b. points out, depending on their situations, other countries may not mind if they experience

inflationary pressure.

Technical Problems:

1. An increase in government purchases (G) will increase the level of output (Y) and interest rates (i).

This will cause an inflow of capital resulting in a higher value of the country's currency. The currency

appreciation will lead to a loss in competitiveness, and net exports (NX) will be crowded out to the

point where the demand for domestic goods is reduced to the original level. In the end, the level of

output and the interest rate will remain unchanged. In an IS-LM model, an increase in G will shift the

IS-curve to the right, increasing both the levels of output (Y) and the interest rate (i). But the decrease

in NX will shift the IS-curve back to the left, until interest rates are back to the world level.

2. A country that is faced with both a recession and a current account deficit should employ

expansionary monetary policy. Expansion in money supply will lower domestic interest rates. This

will not only stimulate domestic investment and output, but also result in a depreciation of the

currency. A lower currency value will increase competitiveness and lead to an increase in the demand

for the country's exports, further stimulating output. In other words, under perfect capital mobility and

flexible exchange rates, monetary expansion will lead to output expansion, currency depreciation, and

a trade balance improvement.

At the root of Finland's problem was the collapse of the Soviet Union (an important trade partner)

and the fall in prices of pulp and paper (important export items). Therefore, expansionary monetary

policy probably would not have been sufficient to remedy the situation. Expansionary fiscal policy

(preferably investment subsidies that are designed to help exporting firms develop new markets) in

combination with some protectionist measures would have been a better policy option.

3.

If the U.S. interest rate is i = 4% and you expect the British pound to depreciate by 6%, then the yield

on British government securities would have to be if =10% or more to make the purchase of British

government securities with U.S. dollars profitable. When capital is perfectly mobile, the domestic

interest rate (i) is equal to the foreign interest rate (if) adjusted for the expected percentage change in

the exchange rate (e), that is,

i = if + (%∆e) ==> if = i - (%∆e) = 4% - (-6%) = 10%.

4. Expansionary fiscal policy (assume an increase in government purchases) will shift the IS-curve to

the right, leading to an increase in the level of output and the interest rate. With perfect capital

190

mobility there will be an inflow of capital that will result in a currency appreciation. Under a fixed

exchange rate system, the central bank will have to respond by increasing the domestic money supply

to avoid currency appreciation. This will shift the LM-curve to the right until the domestic interest

rate is again in line with world interest rates. In this case there is no crowding out and the fiscal policy

will have the full multiplier effect. (Note: The IS-LM framework is a short-run model in which the

prices are assumed to be fixed. But in the longer run, prices can change and then the analysis is

somewhat more complicated.)

i

IS1

IS2

LM1

LM2

i2

if

0

Y1 Y2

Y3

Y

5. Expansionary fiscal policy will have its maximum effect under a fixed exchange rate system with

perfect capital mobility. This is because fiscal expansion must always be combined with monetary

expansion to bring domestic interest rates back in line with foreign interest rates. Expansionary fiscal

policy will increase the level of output demanded and the interest rate. But with perfect capital

mobility, the higher domestic interest rates will attract funds from abroad, which will put upward

pressure on the value of the domestic currency. To avoid currency appreciation, the central bank will

have to increase money supply to bring interest rates back in line with world levels. Therefore, no

crowding out will take place and the level of output will increase by the full multiplier effect.

6.a. In a simple model of the expenditure sector that includes international trade, any change in

autonomous domestic spending by ∆Ao will have the following effect on national income and imports

(disregarding any repercussion effects):

∆Y = [1/(1 - c + m)](∆Ao) and ∆Q = [m/(1 - c + m)](∆Ao).

This can be derived as follows:

Assume that the balance of trade is defined as: NX = X - Q = Xo - Qo - mY.

From Sp = C + I + G + NX ==> Sp = Co + cY + Io - bio + Go + Xo - Qo - mY = Ao - bio + (c - m)Y

with Ao = Co + Io + Go + Xo - Qo, (and assuming that TA = TR = 0, for simplicity)

From Y = Sp ==> Y = Ao - bio + (c - m)Y ==>

191

(1 - c + m)Y = Ao - bio ==> Y = [1/(1 - c + m)](Ao - bio)

Therefore ∆Y = [1/(1 - c + m)](∆Ao)

Since Q = Qo - mY ==> ∆Q = m(∆Y) = [m/(1 - c + m)](∆Ao)

6.b. The increase in the level of output (Y*) in foreign countries due to an increase in their exports (X*)

(our imports) is

∆Q = ∆Xo* = m*(∆Y) and therefore

∆Y* = [1/(s* + m*)](∆Xo*) = [m*/(s* + m*)](∆Y) with s* = 1 - c*.

6.c. From Y = Sp ==> Y = Ao + Xo + (c - m)Y ==> Y = [1/(s + m)](Ao + Xo)

with s = 1 - c ==>

∆Y = [1/(s + m)][(∆Ao) + (∆Xo)] ==> ∆Y* = [m/(s* + m*)][1/(s + m)](∆Ao)

since ∆Xo = (m*)(∆Y*) and ∆Y* = [m*/(s* + m*](∆Y)

6.d. ∆Xo = (m*)(∆Y*) = [m*/(s* + m*)][m/(s + m)](∆Ao)

6.e. Since ∆Y = [1/1 - c + m)][(∆Ao) + (∆Xo)] and 1 - c = s ==>

∆Y = [1/(s + m)]{(∆Ao) + [m*/(s* + m*)][m/(s + m)(∆Ao)]} ==>

∆Y = [1/(s + m)]{1 + [(m*)/(s* + m*)][m/(s + m)]}(∆Ao).

The multiplier with repercussion is larger than the multiplier without repercussion since part of the

import leakage is recovered through increased exports as a consequence of foreign expansion.

6.f. The change in the trade balance without the repercussion effect is

∆NX = - m(∆Y) = [(- m)/(s + m)](∆Ao).

With the repercussion effect, however, the change in the trade balance is

∆NX = ∆Xo - m(∆Y).

But ∆Xo = m*(∆Y*) = [m*/s* + m*)][m/(s + m)](∆Ao) (as derived in 6.d.), and

∆Y = [1/(s + m)]{1 + [m*/(s* + m*)][m/(s + m)]}(∆Ao) (as derived in 6.e.). Hence

∆NX = (sβ - m)/(s + m)(∆Ao) with β = [m*/(s* + m*)][m/(s + m)]

which is clearly less negative than [(- m)/(s + m)](∆Ao).

Because of the induced increase in foreign income, our exports increase, offsetting our increase in

imports. Therefore the adverse effect on the trade balance is dampened by the repercussion effect.

192

Additional Problems:

1. "Fiscal policy cannot change real output under fixed exchange rates and perfect capital

mobility." Comment on this statement.

Expansionary fiscal policy will shift the IS-curve to the right, leading to an increase in the level of output

demanded and a higher interest rate. This will cause an inflow of funds that will result in a currency

appreciation. To maintain a fixed exchange rate, the central bank will have to respond by increasing the

money supply, shifting the LM-curve to the right. Therefore, the level of output demanded will increase

even further. The central bank will continue to increase money supply until the domestic interest rate is

again in line with world interest rates. Thus there will be no crowding out and the level of output will

increase by the full multiplier effect. Therefore the statement is false.

2. "Under a fixed exchange rate system and perfect capital mobility an increase in foreign interest

rates will cause the level of domestic output to rise." Comment on this statement.

If foreign interest rates rise, a capital outflow will occur, leading to a depreciation of the currency. To

maintain a fixed exchange rate, the central bank will be forced to buy domestic currency by selling its

holdings of foreign currency. This reduction in money supply will lead to higher domestic interest rates

and thus less output demanded. This will cause a recession and the level of domestic output will fall, not

rise.

3. True or false? Why?

“If the U.S. dollar price of a Canadian dollar is 0.80, then the Canadian dollar price of a U.S.

dollar is 1.20?

False. The exchange rate e = 0.80 is defined as the domestic currency price of a unit of foreign currency.

Thus the foreign price of a domestic currency unit is 1/e = 1/0.8 = 1.25.

4. "In the early 1980s, U.S. fiscal policy was very expansionary; this helped to foster economic

growth in the rest of the world." Comment on this statement.

The expansionary fiscal policy of the U.S. government, financed by increased borrowing, led to high U.S.

interest rates, which attracted a capital inflow from abroad. The increased demand for the U.S. dollar

caused the dollar to appreciate and U.S. goods became relatively more expensive, leading to a

deterioration in the U.S. trade balance. As U.S. citizens bought more import goods, foreign economic

growth was stimulated. The increase in the national income of foreign countries eventually caused an

increase in the foreign demand for U.S. goods, a good example of the repercussion effect.

5. "A decrease in foreign interest rates will cause domestic output to fall under perfect capital

mobility and flexible exchange rates." Comment on this statement.

If interest rates fall abroad, there will be an inflow of capital here. This will cause an appreciation of the

domestic currency. The price of domestic goods will become relatively more expensive on world markets,

193

resulting in a decrease in net exports. But a decrease in net exports implies a decrease in aggregate

demand for domestic goods, and domestic income and interest rates will go down. (The IS-curve will shift

to the left until a new equilibrium at the new and lower world interest rate is reached.)

6. "The U.S. experience of the early 1980s clearly demonstrated that huge budget deficits do not

necessarily crowd out investment." Comment on this statement.

The huge U.S. budget deficits were financed to a large extent by borrowing from abroad, that is, high U.S.

interest rates attracted foreign funds. This led to an appreciation of the U.S. dollar and U.S. goods became

relatively more expensive on world markets. Large U.S. trade deficits developed as exports declined and

imports increased. Therefore, the increase in the budget deficit did not crowd out investment but instead

crowded out net exports.

7. The re-unification of Germany required a large increase in the German budget deficit since it

became necessary to restructure businesses, provide income support for the unemployed, and

invest in the infrastructure in the new Eastern states. Explain the effects of such massive fiscal

expansion for Germany and its trade partners in the European Union.

The large increase in government spending (which was not financed by an equivalent tax increase or

accommodated by sufficient monetary expansion) resulted in a substantial increase in the German budget

deficit. Since the increase in demand from eastern Germany fell mostly on western German goods, the

Western economy overheated. Interest rates rose sharply, since the Bundesbank did not accommodate the

expansionary fiscal policy. This caused a capital inflow that put upward pressure on the value of the Dmark versus the currencies of non-European trade partners, and a current account deficit resulted.

Initially Germany's European trade partners opted to essentially maintain the exchange rate of their

currencies versus the D-mark. Hence they had to allow the interest rates in their countries to increase to

match those in Germany to avoid a massive outflow of funds. However, since they did not experience the

same fiscal expansion as Germany, these economies' growth rates slowed sharply. Eventually, some

countries had to allow their currencies to depreciate.

8. "By running large budget deficits, the government will attract funds from abroad, which can

then be used to stimulate private investment. This action would be unwise, however, since

foreign countries respond unkindly to such a beggar-thy-neighbor policy." Comment on this

statement.

Expansionary fiscal policy will increase income and interest rates. Higher domestic interest rates will

crowd out investment but will also cause an inflow of funds, resulting in a higher value of the domestic

currency. This will lead to a loss in competitiveness and the crowding out of net exports, while less

investment is crowded out. Other countries are likely to have a mixed reaction to this policy since, on the

one hand, they will experience an outflow of funds, but, on the other hand, their economies will be

stimulated by the increased demand for their goods. This is definitely not a beggar-thy-neighbor policy. A

beggar-thy-neighbor policy is when a country tries to reduce domestic unemployment by depreciating its

currency. This can be achieved by using expansionary monetary policy, which will lower interest rates,

resulting in a capital outflow, lowering the value of the domestic currency. This will increase the demand

194

for domestic goods and lower the demand for foreign goods. As a result, domestic unemployment will

decrease while foreign unemployment will increase

9. "A depreciation-induced change in the trade balance does not work well when different

countries' economic cycles are highly synchronized." Comment on this statement.

Exchange depreciation creates domestic employment at the expense of other countries (this is why it is

called a beggar-thy-neighbor policy). It shifts demand from one country to another but does not change

the level of world demand. When many countries experience a simultaneous economic downturn,

exchange rate movements do not significantly increase world demand, even though they may affect the

allocation of demand among countries. While an individual country may feel compelled to raise domestic

output by attracting demand from other countries, a better way to increase demand in each country would

be to coordinate fiscal and monetary policy.

10. "Under a fixed exchange rate system, expansionary monetary policy depletes foreign reserves at

the central bank." Comment on this statement.

Expansionary monetary policy shifts the LM-curve to the right. The domestic currency will begin to

depreciate. Under a fixed exchange rate system, however, the central bank cannot allow that to happen

and will have to trade foreign currencies for domestic currency, thereby reducing the supply of money.

This will shift the LM-curve back to the left, and the foreign reserve holdings of the central bank will fall.

i

LM1

IS

LM2

i1

i2

0

Y1

Y2

Y

11. Explain how a recession in the United States can affect the economies of other industrial nations.

If the U.S. economy enters a recession, private spending in the U.S. will decline, lowering the demand for

imports. U.S. prices are likely to rise less than those of other countries, which will stimulate U.S. exports,

while discouraging imports. As a result, a recession in the U.S. may contribute to a downturn in other

economies around the world.

12. Explain why a cut in government spending has a larger effect under a fixed exchange rate

system and perfect capital mobility than in a closed economy model.

195

In a closed economy model, restrictive fiscal policy shifts the IS-curve to the left, causing a decrease in

the level of output demanded and the interest rate. The decrease in the interest rate will increase the level

of investment spending. Therefore the level of output demanded will go down by less than the full

amount of the shift in the IS-curve. In the graph below, we move from 1 to 2.

i

IS2

IS1

LM2

LM1

3

i2

i2

1

2

0

Y3 Y2

Y1

Y

In an open economy it gets more complicated, since the lower interest rate will cause an outflow of funds.

This will lead to downward pressure on the value of the domestic currency. If the central bank wants to

maintain the exchange rate, it has to decrease money supply. This will shift the LM-curve to the left and

the level of output demanded will decrease even further. With perfect capital mobility, the central bank

will have to decrease money supply until the domestic interest rate is again at the level of the world

interest rate. Therefore, in the end, the level of investment spending will not be affected and we will have

the full multiplier effect. In the graph above, we will move from 1 to 3.

13. How does a protectionist measure, such as the levying of tariffs on foreign goods, affect the

trade balance, the exchange rate, and the level of domestic output if there is perfect capital

mobility?

If a tariff is imposed, the relative price of imported goods will increase and, as a consequence, the demand

for domestic goods will increase. Domestic income and interest rates will increase, leading to capital

inflows and an appreciation of the currency. This will, in turn, lower the relative price of imported goods

again. With perfect capital mobility the currency appreciation will eventually progress to the point where

the overall change in net exports will be zero. Therefore the level of domestic output and the interest rate

will also be unaffected.

14. Explain how restrictive fiscal policy affects the level and composition of output under flexible

exchange rates and perfect capital mobility.

Restrictive fiscal policy under perfect capital mobility and flexible exchange rates will cause a

depreciation of the domestic currency that will induce a dollar for dollar increase in net exports such that

the level of output demanded will remain unchanged. When government spending is reduced, the IScurve will shift to the left and the domestic interest rate will decline below the level of the world interest

rate. A capital outflow will occur, leading to a depreciation of the domestic currency. Therefore, net

196

exports will increase since the relative price of domestic goods will now be lower. The decrease in net

exports will shift the IS-curve back to its original location. Therefore, the level of output will not change,

although its composition will.

i

IS1

LM

IS2

i1

i2

0

Y2

Y1

Y

15. With the help of an IS-LM diagram show the effect of restrictive monetary policy on output

under flexible exchange rates and with perfect capital mobility.

A decrease in money supply shifts the LM-curve to the left, so interest rates rise while the level of output

demanded decreases. The higher interest rates cause an inflow of capital, which causes the currency to

appreciate. This leads to a decline in exports and an increase in imports, since the relative price of

domestic goods on world markets has increased. The decline in net exports causes the IS-curve to shift to

the left. A new equilibrium will be established at the original interest rate (the world interest rate) but at a

lower level of domestic output.

i

IS2

IS1

LM2

2

LM1

i2

3

i1

1

0

Y3 Y2

Y1

Y

16. "In a flexible exchange rate system with perfect capital mobility, expansionary fiscal policy will

always crowd out net exports." Comment on this statement.

Under perfect capital mobility, the BP-curve is horizontal and domestic interest rates are equal to those in

the rest of the world. Expansionary fiscal policy will shift the IS-curve to the right, increasing the level of

197

output and interest rates. When domestic interest rates are above those in the rest of the world, there will

be a capital inflow that will cause the currency to appreciate. This will lead to a fall in exports and an

increase in imports, since the relative price of domestic goods will increase. This reduction in net exports

will shift the IS-curve back to its original position. In the end, the expansionary fiscal policy will be fully

crowded out by a decrease in net exports.

i

IS1

IS2

LM

i2

BP

i1

0

Y1

Y2

Y

198