第一章 前言 - 高雄海洋科技大學教務處

advertisement

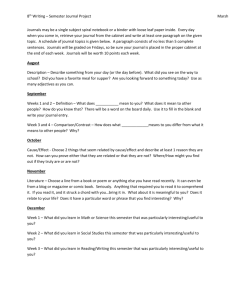

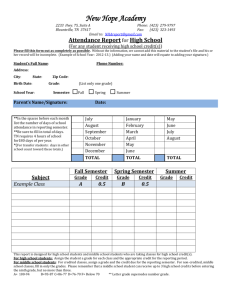

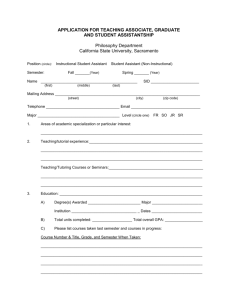

國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 115 Involving Low-Achieving English Learners in Online Reading Journal Writing: Action Research at a Taiwanese Technology University 線上閱讀筆記:科技大學英語低成就學生行動研究 Hsiao-chien Lee 李筱倩 Assistant Professor, Foreign Languages Education Center, National Kaohsiung Marine University 國立高雄海洋科技大學外語教育中心 助理教授 marianlee@webmail.nkmu.edu.tw Abstract This article reports the action research conducted in a freshman English course at a technological university in Taiwan. The aim of the action research is to find an efficient means to motivate my low-achieving English language learning students and to advance their English proficiency. The detail procedures of the action research and the findings obtained from data collection and analysis are presented in the article. Keyword: Internet-based learning, Reading journal, Action research, Low-achieving English learner 摘 要 本研究論文報告了研究者在台灣某科技大學大一英文課程中所做的行動研究,此行 動研究的目的在於找出有效的教學法,以促進修習該課程低成就學生對於學習英文的動 機,並提高他們的英文成就。本文詳盡報告了本行動研究的各項步驟,同時根據數據收 集分析的結果提出成果報告。 關鍵詞:網路輔助學習、閱讀筆記、行動研究、低成就英語學習者 116 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~ INTRODUCTION Technological universities in Taiwan aim to cultivate various industry professionals. The academic projects demonstrate concurrent emphasis on theory and practice. Consequently, in technological universities in Taiwan, it is not uncommon that academic instructions are downgraded to “preparation for job markets” (Zhou, 2007, p.2). Under such circumstances, students’ English proficiency is usually deficient and they are considered low-achievers with English learning difficulties when compared to the students in general universities (Zhou, 2007; Hwang, 2007; Nieh, 2006; Wang 2003). In English class, technological university students in Taiwan may be more likely to experience anxiety (Hsu, 2007), display a lack of motivation (Lee & Su, 2009), and have difficulty when requested to accomplishing a writing task alone (Li, 2004). Teaching at a technology university in Taiwan, I have become aware of the urgent need to find efficient means to approach my students. Action research aims to search for solutions to real problems experienced in schools and look for ways to improve instruction and increase student achievement (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1990; Ferrance, 2000; Hubbard & Power, 1999; Stringer, 2007). I used this approach in my freshman English classroom to find an efficient means to motivate my students in English learning and advance their English proficiency. I followed the suggested phases (see Chart 1, modified from Ferrance, 2000, Rigsby, 2005, and Wadsworth, 1998) and present in this paper the details of my action research cycle and discuss my findings. Chart 1. Cycles of Action Research 國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 117 Reading Response Journals in the English Language Classrooms Reading theorists emphasize the reader’s associations and references in determining meaning (Garber, 1995, p. 7). Rosenblatt (1978/1994) maintains that reading involves a transaction between the reader, the writer, and the text. When readers read, they actively participate by bringing in such resources as their past experience and present personality. Then they form a new order and a new experience (p. 12). Probst (1992a) also states that readers should be encouraged to “attend to their own conceptions, their own experience, bringing the literary work to bear upon their lives and allowing their lives to shed light upon the work” (p. 60). Educators advocating the reader response theory believe that such practices help students assume new perspective about literature, develop students’ ability to respond to readings, create a community of readers that are willing to share interpretations with one another (Serafini, 2002), and give students ownership of their literacy experience (Runkle, 2000). Language educators stress the importance of reading and writing in combination to enhance learning. Reading response journals are considered useful tools to aid students in gaining meaning from text (Au, Mason & Scheu, 1995; Beach, 1998; Calkins, 1986; Hurst, 1999; Langer, 1992; Livdahl, 1993; Reed, 1988; Roessing, 2009). In the English language classrooms, educators advocate the connection of reading and writing (Krashen, 1984; Spack, 1985; Zamel, 1992). They suggest that note taking, working journals, and response statements “can train students to discover and record their own reactions to a text” (Spack, 2001, p. 102). Empirical studies lead teacher-researchers to advocate the implementation of reading response journals in their English language classrooms. Fuhler (1994) promotes informality and spontaneity in response journals, suggesting a form of “first draft chat” (p. 403). Leki (2001) holds that reading journals help students to “negotiate meaning mediated by text” (p. 183), or to “engage intellectually with text” (p. 184). When students write “to the text” in a reading journal, they are not merely led by the text, but rather, make the text their own since they are constructing meaning (p. 185). Students become more active in reading, while the sharing of reading journals in class provides further interaction. Evans (2008) also asserts that the reading reaction journal provides a forum for students when they activate a variety of reading strategies. In addition, it provides a focal point for students as they critically respond to the text (p. 240). Online Reading Journals The statistics show that technological university students in Taiwan spend on average 118 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~ three to five hours daily on the Internet (Wang & Jong, 2007), suggesting that it is promising to incorporate the Internet into school curricula. Accordingly, online reading journal writing should appeal to the students more than pencil and paper journals. The literature also supports online reading journals, revealing that such an approach is beneficial for students in their learning about both the language and the literary works. For example, West (2008) invited her eleventh-grade students to create online reading journals, that is, their own literature-response blogs. The students read, posted, and commented on their own and each other’s blogs while reading literary works. Then West examined students’ blog entries by employing critical discourse analysis method. She identified two major roles students played in this learning experience: “serious literature students” and “Web-literate communicators” (p. 596). The “serious literature students” role helped students stay “normative” as they reflected all English skills in their entries, such as “evaluating characters, defending theories, and describing the process by which they read” (p. 587). On the other hand, students abandoned almost all basic rules of English usage, being “web-literate communicators” (p. 597). The students, as West noticed, based on their knowledge of “the digital nature of current youth culture,” are using “what they know of other discourses to generate new ideas about literature and new ways of communicating their ideas to their peers” (p. 597). Franklin-Matkowski (2007) also employed the blog as the online reading journal in her study. She examined ninth-graders’ blog entries about books, in which students posted their thinking as they read classic thought-provoking novels, such as To Kill a Mockingbird (Lee, 1988). The classroom teacher posted on the blog and explained to the students the focus for each class period (p. 95), while the students read independently and posted on the blogs at their own pace. Then Franklin-Matkowski analyzed students’ blog entries for “writing, specifically fluency and voice, levels of comprehension, and thinking” (p. ix). She particularly explored the correlations between blogging and students’ writing, blogging and literature responses, and blogging and students’ thinking. Franklin-Matkowski’s study confirms the positive influence of this online reading response activity on students’ writing and thinking. PROCESS OF THE ACTION RESEARCH Identification of Problem Area With the support of the above mentioned literature, I resolved to apply an online reading journal project in my freshman English course. The journal, a required course assignment, allowed the students to create response entries after reading individual chapters of a suggested 國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 119 simplified English novel. Forty-four students (three females and forty-one males, majoring in either Shipping Technology or Marine Engineering) were enrolled in the freshman Level B English class, as determined by the school-wide General English Placement Test. Theoretically, the students’ English was at an average level among all the students at the school and had at least six years of English learning experiences prior to university. However, the students’ English proficiency was generally limited, evidenced by the fact that only a few of them had passed the Elementary Level of General English Proficiency Test (GEPT) in Taiwan, a level deemed appropriate for students who have studied English through junior high school. A background information check showed that half of my students believed their English was poor. Only seven students were confident about their English proficiency and12 students thought their English ability was just “all right.” I was encouraged to learn, however, that not all of the students had lost interest in learning English. While 15 students (34%) indicated that they did not like English, nine expressed they did not have specific feeling about English, and16 students (36%) stated that they liked English. Although lacking confidence, the students still expressed enthusiasm, and therefore appropriate instructions should be formulated to approach this group. I chose the online reading journal for this class with the purpose to investigate how the project would motivate my students and consequently lead them to become more confident English learners. I asked the following questions: (1) What are my students’ perceptions of the online reading journal project? (1.1) Do they enjoy participating in the project? (1.2) Do they find the project beneficial to their English learning? (2) How does the project affect my students’ opinions about English reading and writing? (2.1) What are the students’ reading and writing experiences when participating in the project? (2.2) How do the experiences help form their opinions about reading and writing in English? Collection and Organization of Data The school year in Taiwan is divided into two semesters (with 18 weeks in each semester). During the first semester, I asked the students to read outside class and independently the simplified version of an English novel, The Withered Arm (400 Headwords, Oxford Bookworms Library, Oxford University Press). The students had to read an assigned number of pages approximately every other week, and I provided a prompt for the students to respond to. The school’s e-learning Blackboard was used as the medium for the students to post their responses and comment on each other at home. When the students and I met in 120 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~ class (a two-hour session), I shared examples of thoughtful insights displayed in the students’ postings. I collected data from various sources, including the students’ posting entries, an exit-survey conducted at the end of the semester, and observational notes recorded in my teacher’s journal. I also collected students’ pre-project writing samples, planning to use the information at the end of the school year. Altogether the students made 372 reading response postings and 372 comments to one another. I read through all the posting entries and marked noticeable points (i.e. what writing skills were employed and what thought processes students demonstrated in their writing). I examined the students’ answers to the open-ended question asked in the exit survey, “Will you recommend the book to your friends?” for their opinions toward the book and their reading experiences. The exit survey also contained an eight-item five-point Likert Scale questionnaire. Students’ answers in the questionnaire, as well as my observations and informal conversations with the students noted in the teacher’s journal, provided information about their perceptions of the project and their reflections on the learning experiences. I used the constant and comparative method and an inductive research strategy (Merriam, 1998) to code and analyze the data collected qualitatively. Major themes emerged when the analysis was completed. Meanwhile, the answers presented on the Likert Scales were counted and analyzed with Microsoft Excel and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). One student did not complete the Likert Scale exit surveys. Since the missing information was so minimum, the limitation of data collection should not have affected the results of the study. Interpretation of Data Students’ postings Looking through the students’ online journal entries, I saw that my students could usually be categorized into two types. Type one students were opinionated, and their postings were long and thought-out, yet their writings still contained many language errors. The following are two examples. (Excerpts are quoted directly from the online entries with no modifications.) Prompt: What human nature I saw in the story Example One: I saw "jealous" to cause "fear or scare." (Because Rhoda Brook made a picture in her head of the young Mrs. Lodge. When she went to bed that new wife was began slowly appeared in her head) When Rhoda slept, the young wife was still in Rhoda's dreams. Let Rhoda can not 國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 121 have a good night. (That is I saw the human nature in that several-page) So I feel that Rhoda Brook really scared the new wife. In this response, the student used specific details to support his argument, and saw the cause-effect relationship used to justify the character’s motive. Type two students felt uncomfortable about sharing responses in English. Their postings were usually short, not going beyond the minimum requirement. For example, to the same prompt, one student wrote, “I saw in this novel is jealous at old woman and greedy at farmer Lodge. These are bad Human nature. I also see Positive human nature at the kid is pure.” Regardless of which type the students belonged to, their writings often reflected heavy Chinese language influences and direct word-to-word translation from Chinese to English. The exit surveys In the exit survey, I asked one open-ended question, “Will you recommend the book to your friends?” 27 students (61%) marked yes, 12(27%) marked no, and five students (11%) did not give any definite answer. This suggested a generally positive attitude toward the book. However, a closer examination showed that only 20 (45%) of the students were exactly sure why they liked the book. They made statements such as “The plot was interesting” (seven students); or “I learned some lessons from the book” (seven students). Eight students, although indicating that they liked the book, were unable to give any specific reasons. One student wrote: I will recommend the book to my friends. Why? This is a good book. When you read this book, you will know who are Rhoda Brook, Farmer Lodge and Giertrude.” The student went on to summarize the events of the book, and while he might grab the general meaning of the plot, he failed to thoughtfully appreciate the book or make insightful critiques. This might result from a lack of motivation and/or sufficient English skills to read the book carefully enough to make more sophisticated comments. The exit survey also consisted of eight Likert scale items. The following is the summary of the students’ answers. Table 1. Summary of the Likert Scales 1 2 3 Statement I have enjoyed participating in the learning activity. I am satisfied with the teacher’s instructions. My English has improved by participating in the learning activity. Strongly disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (2%) Disagree 2 (5%) 3 (7%) 4 (10%) Un-deci ded 13 (30%) 9 (21%) 21 (50%) Agree 23 (53%) 23 (53%) 15 (36%) Strongly Agree 5 (12%) 8 (19%) 1 (2%) 122 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~ 4 5 6 7 8 Statement I am satisfied with how much I have learned throughout the project. I am satisfied with the effort I have made throughout the project. I am satisfied with my reading performance throughout the project. I am satisfied with my writing performance throughout the project. I am satisfied with my classmates’ engagements in the learning activity. Strongly disagree 0 (0%) 1 (2%) 3 (7%) 2 (5%) 0 (0%) Disagree 2 (5%) 6 (14%) 8 (19%) 17 (40%) 8 (19%) Un-deci ded 24 (56%) 26 (60%) 20 (47%) 17 (40%) 25 (58%) Agree 14 (33%) 9 (21%) 11 (26%) 7 (16%) 9 (21%) Strongly Agree 3 (7%) 1 (2%) 1 (2%) 0 (0%) 1 (2%) The Likert Scales showed that the students were least satisfied with their reading and writing performances throughout the project. Only 12 (28%) students were satisfied with their reading performance, while only seven (16%) with their writing, perhaps suggesting that the students did not gain much confidence in these areas after the first semester. However, it should be noted that these opinions may also be a result of lacking effort, with only ten students (23%) satisfied in this aspect. It is encouraging to note, though, that students enjoyed the project (28 students, 65%) and appreciated the teacher’s instructions (31 students, 72%). After looking at these results, it would be important to find out what hindered the students from learning sufficiently and productively. Notes in the teacher’s journal By recording my observations and informal conversations with the students I was able to gain further understanding about the difficulties my students encountered. I learned that their biggest problem in reading was limited vocabulary. The following examples of the students’ comments (translated from Chinese by me) showed the various types of challenges the students encountered in reading. Table 2. Examples of Students’ Reading Difficulties Difficulties Vocabulary Sentence Structure Comprehension Understanding of Details Quotes from Students ●I had to look up the dictionary all the time, and it was troublesome. ● Some ●I strange sentences were difficult to comprehend. understood the meaning of each sentence; but I didn’t get the meaning of the whole chapter. ● I could understand what the story was generally about, but when it comes to some details, I wasn’t so sure about them. 國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 123 The students’ comments showed that they had difficulties comprehending the texts because of their limited knowledge about English vocabulary and syntax, and I concluded that at their current level asking them to independently read an English novel (although a simplified version) was pushing too hard. The students also met difficulties in writing. Many stated that they did not know what to write about (despite the prompt questions provided), or that they failed to find the right words to express what they had in mind. For example, one student stated, “I was totally at a loss when you asked us to write about the book.” The students were mainly confined by their insufficient English proficiency, and the answer “I don’t know how to express it” was the most common reply they gave when I followed up on their writing. I concluded that requiring the students to accomplish a writing task independently without providing extra assistance could frustrate them. Action Based on Data The students’ perceptions of the online reading journal project and their writing performances reflected an overall enjoyment towards the project. However, instructional strategy refinements were necessary in order to provide more support to the students and accordingly help to remove the hindrances they were encountering as novice English readers and writers. Therefore, while the second semester project requirements remained unchanged, modifications to the approach were made as follows: Selecting a new reading text Krashen’s (1981) input hypothesis proposes that a second language learner must receive a comprehensible input that is at “level i+1,” that is, an input a little beyond where he/she is now. Following Krashen’s suggestion, I chose a book with a higher level (compared to the previous semester), so that my students could be appropriately challenged and also learn something from the reading. A simplified version of Robinson Crusoe (Fast Track Classics, Intermediate level, Evans Publishing Group) was selected. The new text was not only a higher reading level, but also more relevant to the students’ Shipping Technology or Marine Engineering majors, and their life goals to be at sea. Replacing independent reading with teacher-guided reading In order to address the more advanced level of the book, as well as the above mentioned concerns of the students, a major shift from independent reading to teacher-guided reading was made. Every week I devoted half an hour in class to clarify vocabulary and sentences in Chinese, and demonstrated various reading strategies, such as visualizing, making predictions, referring, and making connections to other texts, etc. I also asked questions about the literary elements (such as foreshadowing, similes, metaphors, climax, and conflicts, etc.) to 124 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~ draw students’ attention. Giving students more freedom in writing A list of suggestive topics for discussion gave students more freedom to choose what topics they would like to write about. For example, they could discuss their favorite characters, the plot scenes that surprised them, or the moral lesson they learned from the text. They could also make up a conversation, write a letter to the characters, or create their own story ending. In short, the writing prompts encouraged the students to respond from literature, of literature, and about literature (Probst, 1992b). Providing formal writing instructions on writing techniques In addition to highlighting good writing examples, I also gave mini lessons on grammar to address the difficulties students showed towards expressing their thoughts in English. I discussed subject-verb agreement, uses of tenses, the differences between a sentence and a fragment, and other writing errors that a Chinese-speaking writer tends to make. I even demonstrated how to use the online language tool (such as Google Translate) in a more appropriate way so that the translation from Chinese to English could be more accurate. Assessment I kept recording observations in the journal, collected posting entries, distributed an exit survey at the end of the second semester, and asked the students to compose a pro-project English writing. The goal of the research conducted in the second semester was to find out if the modification of my instructions helped change the students’ perceptions of English reading and writing practices. The data collected and analyzed in the second semester provided the following information: The students held more positive opinions toward the book. 37 out of 44 (84%) indicated that they would recommend the book to their friends, a 23% increase from the previous semester. Students who found the book boring (two students), difficult to read (two students), or that the ending did not answer his questions (one student) did not wish to recommend the book. Two students did not give a definite answer. All of the students (except one) were able to state clearly whether or not they would recommend the book (Table 3): Table 3. Students’ Reasons for Recommending the Book Reason Student Number The story was interesting / exciting. 22 The book taught a lesson (about how to survive in particular). 12 I could learn English words. 6 國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 125 Reason Student Number The book was easy to read. 5 The character(s) were enjoyable. 4 The book fostered thinking. 1 (Unclear) 1 Teacher-guided reading better equipped the students to understand the book and therefore pay attention to the plots, characters, and lessons which they found practical in their future career. The vocabulary that caused them frustration in the previous semester became something they enjoyed learning. The relevance of the book to the students also contributed to the change of opinions. The same student, whose first semester book summary was mentioned earlier, now wrote: “Because this books tell us something things, like to help anybody when they needs to help. And save yourself on the island.” Although the student’s answer to the same question became shorter, it showed a deeper understanding of the text, and instead of just summarizing the plot, he was able to indicate what he liked about the book. Additionally, the students were now all capable of giving opinions about the book in English. The following are two examples: (1) Yes,I do. I think this book is good because these poilt is exciting. Such as Robonsin fight cannibal and cannibak really eat human flesh.They are amazing to me. And this book is not very difficult and I can read easily. It's fit us to read. In sum,it's middle-hard and interesting to fit us to read. Therefore,I will recommend it to my friends. In fact,I already do that. (2) I think I will recommend this book to my friend. because the book likes a turely and simple story.First,in the story,Robinson sometimes funny,but sometimes is serious. His emotion are very different.Second,Friday he is very stupid but cute,too.When I reading this book,I think I was become Robinson,and do everything thing for the story write.This is why I will recommend tihs book to my friends. After one year of practicing writing and responding to literature, the students displayed the ability to evaluate a written text in English. Their answers to the open-ended question, “Will you recommend the book to your friends?” demonstrated that they had become sophisticated readers, and were able to express their thoughts on the book in English. The students felt more confident about their English writing ability. In the second semester, I administrated the same five-point Likert scale questionnaire and adopted a paired samples T-Test to compare the two questionnaires. Two students were 126 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~ absent during the administration of the questionnaire. Since one student was also absent in the first semester, I had 41 rather than 44 as the valid number for the participating students. Table 4. Paired Samples T-Test of the Questionnaire Answers As the statistics show, a significance of difference occurred in Question 7 (M=.500, s=1.534, t(40)=.041), regarding writing performance satisfaction, and in Question 8 (M=.381, s=1.035, t(40)=.022), which gauged students’ satisfaction with their classmates’ engagements in the learning activity. Compared to the first semester, the students felt more satisfied with their writing performances. They also thought that their classmates were more devoted to the learning activity in the second semester. Therefore, after the modification of my instructions and after another semester of practice in English writing, the students became more confident English writers. Although the comparisons between the other pairs of questions did not show any significant changes, a closer look at the mean values could offer more information. Table 5. Comparisons of Means Item (1st Semester) Mean Item (2nd Semester) Mean A1 3.76 B1 3.81 A2 3.86 B2 3.93 A3 3.19 B3 3.24 國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 127 Item (1st Semester) Mean Item (2nd Semester) Mean A4 3.43 B4 3.60 A5 3.07 B5 3.21 A6 3.00 B6 3.21 A7 2.69 B7 3.19 A8 3.07 B8 3.45 Table 5 displays a mean value increase in each Likert scale item during the second semester, indicating that the students became more satisfied with their learning performances, teacher instructions, and overall enjoyment towards participating in the project. The students’ writing scores improved. In order to check if my students held false belief about their English writing performances, I invited two experienced English language teachers to grade the students’ preand post-project writings. I used Pearson Correlations to calculate the inter-rater reliability of the two English teachers and there was a strong, positive correlation between the two teachers’ grading (for pre-project writings: r = 0.858, n = 44, p = .000; for post-project writings: r = 0.680, n = 44, p = .000). Then I used a Paired Samples T-Test to compare the averaged writing scores the students received for their pre-project and post-project writings. The result (Table 6) revealed a statistically reliable difference between the two sets of averaged scores, t(43) = 6.869, p = .000, α = .05., indicating a significant increase in the students’ writing levels. Table 6. Paired Samples T-Test of Students’ Writing Scores Paired Differences Pair 1 average _1st average _2nd Mean Std. Deviation Std. Error Mean -.9205 .8888 .1340 t df Sig. (2-tailed) -6.869 43 .000 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference Lower Upper -1.190 7 -.6502 CONCLUSION Constant and regular writing practices contributed to students’ positive and productive 128 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~ learning experiences, and helped boost students’ confidence in their writing abilities. In this study, students’ writing scores improved after participation in the project. However, while they had insightful thoughts about the books, they were confined and sometimes frustrated by their limited English proficiency. Therefore, formal language instruction needs to be particularly addressed so that students can appropriately and comfortably express themselves in English. Teachers should also provide sufficient scaffolding before requiring students to do independent reading, particularly with low-achieving students who have limited vocabulary knowledge. In the beginning of the study, many students held a negative attitude toward the reading text, but an adaptation to teacher-guided reading allowed the students to become more sophisticated readers, better understanding and enjoying the reading task. Although the students might have encountered difficulties with reading and writing, participating in the online reading journal project was still an exciting experience to them. The students embraced and appreciated the alternative approach to learning English. The online journal provided an outlet to share reading responses within a community, and the flexibility of time, space, and free choice of writing topics enabled them to be engaged in the learning activity. By the end of the school year, when my students requested, “I’d like to do the same activity next year,” I felt that as their instructor, I had found a way to approach and motivate my students. The action research I conducted throughout the year shed a new light on my future pedagogical practices. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article. REFERENCES [1] Au, K. H., Mason, J. M., & Scheu, J. A. (1995). Literacy instruction for today. New York: HarperCollins. [2] Beach, R. (1998). Writing about literature: A dialogic approach. In N. Nelson & R.C.Calfee (Eds.), The reading-writing connection: Ninety-seventh yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, Part II (pp. 229-248). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [3] Calkins, L. M. (1986). The art of teaching writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. 國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 129 [4] Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (1990). Teacher research and research on teaching: The issues that divide. Educational Researcher, 19 (2), 2-11. [5] Ferrance, E. (2000). Themes in education: Action research. Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory At Brown University. Retrieved October 28, 2010 from http://www.alliance.brown.edu/pubs/themes_ed/act_research.pdf [6] Franklin-Matkowski, K. (2007). Blogging about books: Writing, reading, and thinking in a twenty-first century classroom. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri. [7] Fuhler, C.J. (1994, February). Response journals: Just one more time with feeling. Journal of Reading 37, 400-405. [8] Garber, K.S. (1995). The effects of transmissional, transactional, and transformational reader-response strategies on middle school students’ thinking complexity and social development. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Missouri-Kansas City. [9] Hsu, S.-c. (2007, March). Foreign language anxiety among technical college students in English class. Journal of National Huwei University of Science & Technology 28(1), 113-126. [10] Hubbard, R.S. & Power, B.M. (1999). Living the questions: A guide for teacher-researchers. Portland, Maine: Stenhouse Publishers. [11] Hurst, B. (1999). Living learning logs. Journal of Reading Education, 24(3), 34-35. [12] Hwang, S.-m. (2007). Learning strategy use and persuasive writing performance: A study on commercial college students. Unpublished Master Thesis, National Pingtung Institute of Commerce. [13] Krashen, S.D. (1981). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. London: Prentice-Hall International (UK) Ltd. [14] Krashen, S.D. (1984). Writing: Research, theory, and applications. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [15] Langer, J.A. (1992). Rethinking literature instruction. In J.A. Langer (Ed.), Literature instruction: A focus on student response (pp. 35-53). Urbana, IL National Council of Teachers of English. [16] Lee, C.-l. & Su, H.-h. (2009). The effectiveness of English ability-grouping teaching—A case study of a university of technology in central Taiwan, Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(1), 233-251. [17] Lee, H (1988). To kill a mockingbird. New York: Grand Central Publishing. [18] Leki, I. (2001). Reciprocal themes in ESL reading and writing. In Silva, T. & Matsuda, 130 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~ P.K. (Eds.), Landmark essays on ESL writing (pp. 173-190). Mahwah, NJ: Hermagoras Press. [19] Li, C.-l. (2004). An analytical study of errors in college students’ English writing: A case study at Mei-Ho Institute of Technology. Journal of Da-Yeh University, 13(2), 19-37. [20] Livdahl, B.S. (1993). To read it is to live it, different from just knowing it. Journal of Literacy Research, 37(3), 192-200. [21] Merriam, S.B. (Ed.) (2002). Qualitative research in practice: Examples for discussion and analysis. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [22] Nieh, P.-l. (2006). Developing a virtual EFL center at STUT for remedial instruction. Journal of Southern Taiwan University, 31, 221-231. [23] Probst, R.E. (1992a). Five kinds of literary knowing. In J.A. Langer (Ed.), Literature instruction: A focus on student response (pp. 54-77). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. [24] Probst, R.E. (1992b). Writing from, of, and about literature. In N.J. Karolides. (Ed.), reader response in the classroom: Evoking and interpreting meaning in literature (pp. 117-127). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [25] Reed, S. D. (1988). Logs: Keeping an open mind. English Journal, 77, 52-56. [26] Rigsby, L.C. (2005). Action research: How is it defined? Power-point presented at George Mason University. Retrieved December 12, 2010 from http://gse.gmu.edu/assets/media/tr/ARRigsbyppt.htm [27] Roessing, L.J. (Ed.), (2009). The write to read: Response journals that increase comprehension. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. [28] Rosenblatt, L.M. (1978/1994). The reader, the text, the poem. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. [29] Runkle, D.R. (2000, April). Effectively using journals to respond to literature. Schools in the Middle, 9(8), 35-36. [30] Serafini, F. (2002). A journey with the Wild Things: A reader response perspective in practice. Journal of Children’s Literature, 28(1), 73-78. [31] Spack, R. (1985). Literature, reading, writing, and ESL: Bridging the gaps. TESOL Quarterly, 19, 703-725. [32] Spack, R. (2001). Initiating ESL students into the academic discourse community: How far should we go? In T. Silva & P.K. Matsuda (Eds.), Landmark essays on ESL writing (pp. 91-108). Mahwah, NJ: Hermagoras Press. [33] Stringer, E. (2007). Action research (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 國立高雄海洋科技大學學報 第二十六期 131 Inc. [34] Wadsworth, Y. (1998). What is participatory action research? Action Research International. Retrieved December 12, 2010 from http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ ar/ari/ p-ywadsworth98.html [35] Wang, T.-s. & Jong, D. (2007). The analysis of technical university students' Internet usage. Tajen Journal, 35, 53-66. [36] Wang, Y.-h. (2003). An exploration into current teaching innovation and strategy in commercial colleges. Technological and Vocational Education Journal Bimonthly, 75. [37] West, K.C. (2008). Weblogs and literary response: Socially situated identities and hybrid social languages in English. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 51(7), 588-598. [38] Zamel, V. (1992). Writing one’s way into reading. TESOL Quarterly, 26, 463-485. [39] Zhou, S.-g. (2007).我國英語教育政策對各級英語教學之影響-英語教育政策對技職 體系高等教育英語教學影響之調查研究(Ⅱ)。Unpublished National Science Council Project Report (No: NSC962411H218009). 132 台灣東部新協發與佳豐定置漁場漁況變動比較分析(II)~季節別漁獲組成與產量分析~