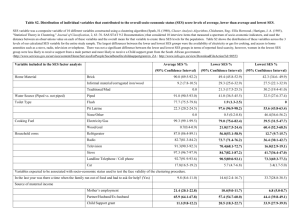

Ten Hypotheses about Socioeconomic Gradients and

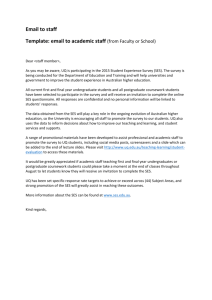

advertisement