Plantation Slavery and Economic Development in the

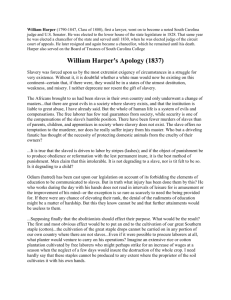

advertisement