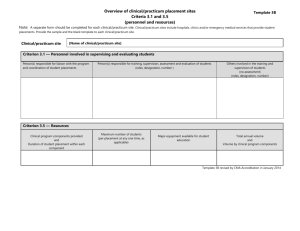

Last Revised December 2010 - School of Social Work

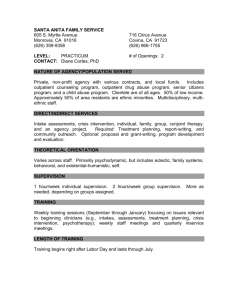

advertisement