2

Filling a Void

When there’s a hole in our clothing, we either mend or replace the

garment. But what action do we take when we discover a hole in

our lives? The selections in this theme show many different ways

people try to mend the holes, or fill the voids, in their lives. What is

the thing you—or the people you know—yearn for most?

THEME PROJECTS

Performing

Act It Out Have you ever wished you could

meet someone you read about or watched on

screen? Now you can give your characters the

chance to do just that.

1. Make a list of the characters in this theme

who are particularly interesting to you.

Choose no more than one character from

each story.

2. Write a skit in which two of the characters

meet each other. You may base your skit on

what might happen if one of the characters

entered the story of the other, or you may

create a totally new scenario.

3. Perform your skit for the class.

Listening and Speaking

Finding Fulfillment There are many different

ways to find fulfillment in life.

1. Identify the void that each main character in

this theme faces.

2. Interview your friends and family members

to find out how they might fill these voids.

Be sure to take notes. You may want to use

a hand-held tape recorder to collect quotes.

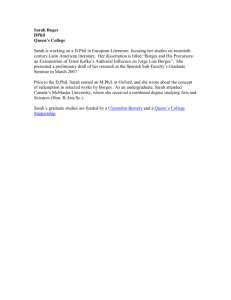

Two Figures (Menhirs), 1964.

Dame Barbara Hepworth. Stone

sculpture, 756 x 635 x 330 mm.

Tate Gallery, London.

3. Which suggested paths to fulfillment were

similar to those actually taken by the

characters in the stories? Compare the

responses you’ve gathered with those of

your classmates. Which suggestions were

recorded most often?

Comic Strip

Do you play an active role in your daydreams, or do you dream about other

people and places? As you can see in

the comic below, Calvin is a space

explorer in his daydreams.

Calvin and Hobbes

CALVIN & HOBBES ©1987 Watterson. Dist. by UNIVERSAL PRESS SYNDICATE.

Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

by Bill Watterson

Analyzing Media

1. What are some possible reasons for Calvin’s vivid daydream? What

might he be trying to avoid? Explain.

2. The teacher’s question becomes a part of Calvin’s daydream. At the

same time, her voice brings him back into reality. How do your surroundings lead you into daydreams? How do they wake you up?

114

UNIT 1

Before You Read

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

Reading Focus

What are some reasons why you daydream?

Connect It! Think about what you are doing when you daydream. For example, you might daydream while watching a boring

movie or while being scolded by an adult. Make a diagram like this one

to help you find relationships between when you daydream and why.

When

Why

When

Why

When

Why

Setting a Purpose Read to learn when and why Walter Mitty

daydreams—and what he daydreams about.

Building Background

The Time and Place

This story takes place in Waterbury, Connecticut, a suburb of New York

City. It is winter, sometime after World War I.

Did You Know?

This story includes a person’s daydreams about heroic real-life situations,

but many of the details of these situations are invented. For example,

one daydream includes an eight-engine Navy hydroplane, but there is no

such thing. Its commander orders full strength from the turrets to get out

of a storm, but turrets are structures on which guns rotate; they have

nothing to do with engine power. Other fractured facts include a medical

diagnosis of obstreosis in the ductal tract—a disease that cannot afflict

humans in a part of the body that doesn’t even exist—and a reference to

a 50.80 caliber pistol, which in reality would be bigger than a cannon!

Vocabulary Preview

distraught (dis trot) adj. very upset; confused; p. 117

haggard (haərd) adj. having a worn and tired look; p. 117

craven (krā vən) adj. extremely cowardly; p. 118

insolent (insə lənt) adj. so rude or proud as to be offensive; p. 118

insinuatingly (in sinū āt´in lē) adv. in an indirect way; p. 118

pandemonium (pan´də mō nē əm) n. wild uproar; p. 119

disdainful (dis dānfəl) adj. showing scorn for something or someone

regarded as unworthy; p. 120

Meet

James Thurber

When he was six years old, James

Thurber stood with an apple on

his head while his older brother

aimed a homemade arrow at the

fruit. The arrow pierced Thurber’s

left eye, blinding him in that eye.

As Thurber grew older, the vision

in his right eye grew increasingly

worse, but this didn’t prevent him

from living a successful life. In

1927 he began writing for The

New Yorker magazine, delighting

readers with his humorous stories,

essays, and cartoons. Although

Thurber was completely blind in

his later years, he continued his

job at The New Yorker until the

end of his life.

James Thurber was born in 1894 in

Columbus, Ohio, and died in New York

City in 1961. This story was published in

My World—and Welcome to It in 1942.

THE SHORT STORY

115

James Thurber

“We’re going through!” The Commander’s voice was like thin ice

breaking. He wore his full-dress uniform, with the heavily braided

white cap pulled down rakishly1 over one cold gray eye. “We can’t

make it, sir. It’s spoiling for a hurricane, if you ask me.”

“I’m not asking you, Lieutenant Berg,”

said the Commander. “Throw on the

power lights! Rev her up to 8,500!

We’re going through!” The pounding

of the cylinders increased: ta-pocketapocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa.

The Commander stared at the ice

forming on the pilot window. He

walked over and twisted a row of complicated dials. “Switch on No. 8 auxiliary!” he shouted. “Switch on No. 8

auxiliary!” repeated Lieutenant Berg.

“Full strength in No. 3 turret!” shouted

the Commander. “Full strength in No.

3 turret!” The crew, bending to their

various tasks in the huge, hurtling

eight-engined Navy hydroplane,2

looked at each other and grinned.

“The Old Man’ll get us through,” they

said to one another. “The Old Man

ain’t afraid of Hell!” . . .

“Not so fast! You’re driving too

fast!” said Mrs. Mitty. “What are you

driving so fast for?”

1. Rakishly means “in a dashing or jaunty manner.”

2. A hydroplane is an airplane equipped with floats

that allow it to take off from and land on water.

116

UNIT 1

Decisive Seconds—Far Over There Above the Enemy on Enemy

Reconnaissance, 1929. A. B. Henninger. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

“Hmm?” said Walter Mitty. He looked at

his wife, in the seat beside him, with shocked

astonishment. She seemed grossly unfamiliar,

like a strange woman who had yelled at him

in a crowd. “You were up to fifty-five,” she

said. “You know I don’t like to go more than

forty. You were up to fifty-five.” Walter Mitty

drove on toward Waterbury in silence, the

roaring of the SN202 through the worst

storm in twenty years of Navy flying fading

in the remote, intimate airways of his mind.

“You’re tensed up again,” said Mrs. Mitty.

“It’s one of your days. I wish you’d let Dr.

Renshaw look you over.”

Walter Mitty stopped the car in front of

the building where his wife went to have her

hair done. “Remember to get those overshoes while I’m having my hair done,” she

said. “I don’t need overshoes,” said Mitty.

She put her mirror back into her bag.

“We’ve been all through that,” she said, getting out of the car. “You’re not a young man

any longer.” He raced the engine a little.

“Why don’t you wear your gloves? Have you

lost your gloves?” Walter Mitty reached in a

pocket and brought out the gloves. He put

them on, but after she had turned and gone

into the building and he had driven on to a

red light, he took them off again. “Pick it

up, brother!” snapped a cop as the light

changed, and Mitty hastily pulled on his

gloves and lurched ahead. He drove around

the streets aimlessly for a time, and then he

drove past the hospital on his way to the

parking lot.

. . . “It’s the millionaire banker, Wellington

McMillan,” said the pretty nurse. “Yes?” said

Walter Mitty, removing his gloves slowly.

“Who has the case?” “Dr. Renshaw and Dr.

Benbow, but there are two specialists here,

Dr. Remington from New York and Mr.

Pritchard-Mitford from London. He flew

over.” A door opened down a long, cool

corridor and Dr. Renshaw came out. He

looked distraught and haggard. “Hello, Mitty,”

he said. “We’re having the devil’s own time

with McMillan, the millionaire banker and

close personal friend of Roosevelt. Obstreosis

of the ductal tract. Tertiary. Wish you’d take

a look at him.” “Glad to,” said Mitty.

In the operating room there were whispered introductions: “Dr. Remington, Dr.

Mitty. Mr. Pritchard-Mitford, Dr. Mitty.”

“I’ve read your book on streptothricosis,”

said Pritchard-Mitford, shaking hands. “A

brilliant performance, sir.” “Thank you,” said

Walter Mitty. “Didn’t know you were in the

States, Mitty,” grumbled Remington. “Coals

to Newcastle,3 bringing Mitford and me up

here for a tertiary.” “You are very kind,” said

Mitty. A huge, complicated machine, connected to the operating table, with many

tubes and wires, began at this moment to

go pocketa-pocketa-pocketa. “The new anesthetizer is giving way!” shouted an intern.

“There is no one in the East who knows how

to fix it!” “Quiet, man!” said Mitty, in a low,

cool voice. He sprang to the machine, which

was now going pocketa-pocketa-queep-pocketaqueep. He began fingering delicately a row

of glistening dials. “Give me a fountain

pen!”4 he snapped. Someone handed him a

fountain pen. He pulled a faulty piston out

of the machine and inserted the pen in its

place. “That will hold for ten minutes,” he

3. Carrying coals to Newcastle would be a waste of time and

energy, since Newcastle, England, is a coal-mining town.

4. A fountain pen has a reservoir or replaceable cartridge that

automatically feeds a steady supply of ink to the writing

point.

Vocabulary

distraught (dis trot) adj. very upset; confused

haggard (haərd) adj. having a worn and tired look

THE SHORT STORY

117

said. “Get on with the operation.” A nurse

hurried over and whispered to Renshaw, and

Mitty saw the man turn pale. “Coreopsis5 has

set in,” said Renshaw nervously. “If you

would take over, Mitty?” Mitty looked at

him and at the craven figure of Benbow,

who drank, and at the grave, uncertain faces

of the two great specialists. “If you wish,” he

said. They slipped a white gown on him; he

adjusted a mask and drew on thin gloves;

nurses handed him shining . . .

“Back it up, Mac! Look out for that Buick!”

Walter Mitty jammed on the brakes. “Wrong

lane, Mac,” said the parking-lot attendant,

looking at Mitty closely. “Gee. Yeh,” muttered

Mitty. He began cautiously to back out of the

lane marked “Exit Only.” “Leave her sit there,”

said the attendant. “I’ll put her away.” Mitty

got out of the car. “Hey, better leave the key.”

“Oh,” said Mitty, handing the man the ignition key. The attendant vaulted into the car,

backed it up with

insolent skill, and put

it where it belonged.

They’re so damn

cocky, thought Walter

Mitty, walking along

Main Street; they think

they know everything.

Did You Know?

Once he had tried to

In some areas, people put

take his chains off, outchains on tires to provide betside New Milford, and

ter traction on ice and snow.

he had got them wound

around the axles. A man had had to come out

in a wrecking car and unwind them, a young,

grinning garageman. Since then Mrs. Mitty

5. If coreopsis really has set in, the patient may need a gardener. This is the name of a daisy-like flowering plant.

always made him drive to a garage to have the

chains taken off. The next time, he thought,

I’ll wear my right arm in a sling; they won’t

grin at me then. I’ll have my right arm in a

sling and they’ll see I couldn’t possibly take

the chains off myself. He kicked at the slush

on the sidewalk. “Overshoes,” he said to himself, and he began looking for a shoe store.

When he came out into the street again,

with the overshoes in a box under his arm,

Walter Mitty began to wonder what the other

thing was his wife had told him to get. She

had told him, twice, before they set out from

their house for Waterbury. In a way he hated

these weekly trips to town—he was always getting something wrong. Kleenex, he thought,

Squibb’s, razor blades? No. Toothpaste, toothbrush, bicarbonate, carborundum, initiative

and referendum? 6 He gave it up. But she would

remember it. “Where’s the what’s-its-name?”

she would ask. “Don’t tell me you forgot the

what’s-its-name.” A newsboy went by shouting

something about the Waterbury trial.

. . . “Perhaps this will refresh your memory.” The District Attorney suddenly thrust

a heavy automatic at the quiet figure on the

witness stand. “Have you ever seen this

before?” Walter Mitty took the gun and

examined it expertly. “This is my WebleyVickers 50.80,” he said calmly. An excited

buzz ran around the courtroom. The Judge

rapped for order. “You are a crack shot

with any sort of firearms, I believe?” said

the District Attorney, insinuatingly.

6. Mitty’s shopping list is partially nonsense: Carborundum is

the brand name of an industrial compound used to grind and

polish, an initiative is a procedure enabling voters to propose

new laws, and a referendum is a direct popular vote on a

public issue.

Vocabulary

118

craven (krā vən) adj. extremely cowardly

insolent (insə lənt) adj. so rude or proud as to be offensive

insinuatingly (in sinū āt´in lē) adv. in an indirect way

UNIT 1

James Thurber

“Objection!” shouted Mitty’s attorney. “We

have shown that the defendant could not

have fired the shot. We have shown that he

wore his right arm in a sling on the night of

the fourteenth of July.” Walter Mitty raised

his hand briefly and the bickering attorneys

were stilled. “With any known make of gun,”

he said evenly, “I could have killed Gregory

Fitzhurst at three hundred feet with my left

hand.” Pandemonium broke loose in the

courtroom. A woman’s scream rose above

the bedlam and suddenly a lovely, darkhaired girl was in Walter Mitty’s arms. The

District Attorney struck at her savagely.

Without rising from his chair, Mitty let the

man have it on the point of the chin. “You

miserable cur!” . . .7

“Puppy biscuit,” said Walter Mitty. He

stopped walking and the buildings of

Waterbury rose up out of the misty courtroom

and surrounded him again. A woman who

was passing laughed. “He said ‘Puppy

biscuit,’ ” she said to her companion. “That

man said ‘Puppy biscuit’ to himself.” Walter

Mitty hurried on. He went into an A. & P.,8

not the first one he came to but a smaller one

farther up the street. “I want some biscuit for

small, young dogs,” he said to the clerk. “Any

special brand, sir?” The greatest pistol shot in

the world thought a moment. “It says ‘Puppies

Bark for It’ on the box,” said Walter Mitty.

His wife would be through at the hairdresser’s

in fifteen minutes, Mitty saw in looking at

his watch, unless they had trouble drying it;

sometimes they had trouble drying it. She

7. A cur can be either a mean, rude person or a mixedbreed dog.

8. A. & P., short for Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, is a chain of

grocery stores.

didn’t like to get to the hotel first; she would

want him to be there waiting for her as usual.

He found a big leather chair in the lobby,

facing a window, and he put the overshoes

and the puppy biscuit on the floor beside it.

He picked up an old copy of Liberty and sank

down into the chair. “Can Germany Conquer

the World Through the Air?” Walter Mitty

looked at the pictures of bombing planes and

of ruined streets.

. . . “The cannonading has got the wind

up in young Raleigh, sir,” said the sergeant.

Captain Mitty looked up at him through

touseled hair. “Get him to bed,” he said wearily.

“With the others. I’ll fly alone.” “But you

can’t, sir,” said the sergeant anxiously. “It

takes two men to handle that bomber and the

Archies are pounding hell out of the air. Von

Richtman’s circus is between here and

Saulier.”9 “Somebody’s got to get that ammunition dump,” said Mitty. “I’m going over. Spot

of brandy?” He poured a drink for the sergeant

and one for himself. War thundered and

whined around the dugout and battered at the

door. There was a rending of wood and splinters flew through the room. “A bit of a near

thing,” said Captain Mitty carelessly. “The box

barrage10 is closing in,” said the sergeant. “We

only live once, Sergeant,” said Mitty, with his

faint, fleeting smile. “Or do we?” He poured

another brandy and tossed it off. “I never see a

man could hold his brandy like you, sir,” said

the sergeant. “Begging your pardon, sir.”

Captain Mitty stood up and strapped on his

9. Mitty blends fantasy with the realities of World War I.

Archies was the British name for anti-aircraft guns and their

shells. Von Richtman suggests Manfred von Richthofen, the

German flying ace known as the Red Baron. Saulier appears

to be a made-up name for a town in France.

10. Box barrage refers to artillery fire used to hold back the

enemy or to protect one’s own soldiers.

Vocabulary

pandemonium (pan´də mō nē əm) n. wild uproar

THE SHORT STORY

119

11. “Auprès de Ma Blonde” (ō prā də ma blōnd) is a

French song (“Near My Blonde”) that was popular during

World War I.

12. Derisive (di r¯ siv) means mocking, jeering, or ridiculing.

© Estate of Grant Wood/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

huge Webley-Vickers automatic. “It’s forty

kilometers through hell, sir,” said the sergeant.

Mitty finished one last brandy. “After all,” he

said softly, “what isn’t?” The pounding of the

cannon increased; there was the rat-tat-tatting

of machine guns, and from somewhere came

the menacing pocketa-pocketa-pocketa of the

new flame-throwers. Walter Mitty walked to

the door of the dugout humming “Auprès de

Ma Blonde.”11 He turned and waved to the

sergeant. “Cheerio!” he said. . . .

Something struck his shoulder. “I’ve been

looking all over this hotel for you,” said Mrs.

Mitty. “Why do you have to hide in this old

chair? How did you expect me to find you?”

“Things close in,” said Walter Mitty vaguely.

“What?” Mrs. Mitty said. “Did you get the

what’s-its-name? The puppy biscuit? What’s

in that box?” “Overshoes,” said Mitty.

“Couldn’t you have put them on in the

store?” “I was thinking,” said Walter Mitty.

“Does it ever occur to you that I am sometimes thinking?” She looked at him. “I’m

going to take your temperature when I get

you home,” she said.

They went out through the revolving

doors that made a faintly derisive12 whistling

sound when you pushed them. It was two

blocks to the parking lot. At the drugstore on

the corner she said, “Wait here for me. I forgot something. I won’t be a minute.” She was

more than a minute. Walter Mitty lighted a

Sentimental Yearner, 1936. Grant Wood. Pencil, black and white

conte crayon, 20¹⁄₂ x 16 in. The Minneapolis Institute of the Arts, MN.

Viewing the art: How would you describe this man to someone else? What might he and Walter Mitty have in common?

cigarette. It began to rain, rain with sleet in

it. He stood up against the wall of the drugstore, smoking. . . . He put his shoulders back

and his heels together. “To hell with the

handkerchief,” said Walter Mitty scornfully.

He took one last drag on his cigarette and

snapped it away. Then, with that faint, fleeting smile playing about his lips, he faced the

firing squad; erect and motionless, proud and

disdainful, Walter Mitty the Undefeated,

inscrutable13 to the last.

13. Inscrutable (in skr¯¯¯

ootə bəl) means “mysterious.”

Vocabulary

disdainful (dis dānfəl) adj. showing scorn for something or someone regarded as

unworthy

120

UNIT 1

Active Reading and Critical Thinking

Responding to Literature

Personal Response

Did you identify with Walter Mitty as you read the story? Explain why

or why not.

Analyzing Literature

Recall

1. What does Mitty’s wife ask him to do while she’s at the hairdresser?

2. Describe two of Mitty’s daydreams.

3. Aside from his wife, which other characters scold Mitty while he’s

behind the wheel of his car? Why do they talk to him this way?

4. How does Mitty’s wife greet him at the hotel?

5. What is Mitty doing at the end of the story?

Interpret

6. How does Walter Mitty feel about the errands his wife asks him to run?

Why does he do what his wife tells him to do?

7. What is ironic about the way Mitty sees himself in his daydreams?

(See Literary Terms Handbook, page R7.)

8. Mitty thinks the parking attendant and other young men are cocky.

What does this tell you about how he thinks of himself?

9. What does Mitty’s conversation with his wife at the hotel tell you about

their relationship? Explain your answer.

10. Reread the last line of the story. How do the adjectives used to describe

Mitty compare or contrast with the way he sees himself in his daydreams? How do they compare or contrast with the way he really is?

Evaluate and Connect

11. Which parts of this story, if any, do you find funny? How does

Thurber’s use of factual distortions, some of which are explained in the

Background section of page 115, contribute to the story’s humor?

12. How would you like being married to someone like Walter Mitty? How

would you like being married to someone like Mrs. Mitty? Explain.

13. Imagine that you are Walter Mitty and complete the diagram shown in

the Reading Focus on page 115. Then compare and contrast your own

reasons for daydreaming with those of Walter Mitty.

14. What is the main conflict in this story? (See page R3.) Is the conflict

resolved in a way that is satisfying to you? Why or why not?

15. Theme Connections What is missing in Walter Mitty’s life? How

does he try to fill this void? Explain what you think of his approach.

Literary

ELEMENTS

Dialogue

Dialogue is the conversation that takes

place between characters in a literary

work. Writers use dialogue to reveal

characters’ personalities and traits. For

example, a parking lot attendant who

shouts, “Back it up, Mac! Look out for

that Buick!” is probably disrespectful

and alert. Dialogue brings characters

to life by showing what they are thinking and feeling as they react to other

characters.

1. How do the characters in Mitty’s

daydreams speak to him? What

does this suggest to you about why

he would prefer daydreams to reality? Give examples from the story to

support your answer.

2. Compare the way Mitty speaks to

other people in his daydreams with

the way he speaks to his wife. What

does this comparison tell you about

Mitty?

3. How does Mrs. Mitty talk to her

husband in this story? How does

her dialogue reveal her character?

• See Literary Terms Handbook,

p. R4.

THE SHORT STORY

121

Responding to Literature

Literature and Writing

Writing About Literature

Creative Writing

Character Sketch Brainstorm a list of character traits

that Walter Mitty exhibits in this story, using a chart like

the one below to help you organize your thoughts. Be

sure to include a sentence or an incident from the story

that illustrates each character trait. Then write a brief character sketch of Mitty, using the information in your chart.

Compare your sketch with those of other students.

Mitty Steps Up to Bat Walter Mitty’s daydreams are

usually triggered by something he sees or by another

character’s words. Use your imagination to write a daydream that Walter Mitty might have as he passes a baseball diamond or a university or visits any other site of

potential drama. As you’re writing your passage, try to

include some of the elements that link the daydreams

with the narration in the story.

Character traits

Examples

Mitty’s public life

Mitty’s private life

Extending Your Response

Literature Groups

Listening and Speaking

Critique the Critic Literary critic Carl M. Linder once

remarked that in this story, Thurber touched upon one of

the major themes in American literature: the conflict

between individual and society. Do you agree that this

story is about a conflict between an individual and society? Debate this question within your group and try to

reach a consensus. Explain your opinions to the rest of the

class, using specific passages or details from the story to

support your opinions.

Dramatic Reading With a small group, organize and

present a dramatic reading of “The Secret Life of Walter

Mitty.” Select a director and a person to create sound

effects and then assign actors to play the different roles.

(In order to perform the daydream sequences, some

actors may need to play the parts of two or more

characters.) Rehearse the story until you can perform it

smoothly and then present it to the class.

Learning for Life

You might enjoy these works by James Thurber:

Collections: The Thurber Carnival includes some of

Thurber’s best stories and drawings.

Fables for Our Times puts a humorous twist on classic

poems and fables such as “Little Red Riding Hood.”

Children’s Story: Many Moons is the story of a young

princess who wanted the moon and her father’s efforts to

get it for her.

Your Dream Job Daydream for a few minutes about a

job that you might like to have some day. Then write a job

description listing the education, experience, and abilities

that you believe one must have for your dream job. Also

describe the opportunities for advancement this job

may offer.

Reading Further

Literary Criticism

“Mitty’s fantasies,” comments critic Anthony Kaufman,

“may reveal a longing for the heroic, but much of the

delight of the story comes from our perception of how

formulaic, superficial, and false to life they really are.” Is

this how you perceive Mitty’s fantasies? Write a short paragraph in which you explain whether you agree with

Kaufman’s assessment.

Save your work for your portfolio.

122

UNIT 1

Skill Minilessons

GRAMMAR AND LANGUAGE

A proper noun is the name of a particular person, place,

thing, or idea. Proper nouns should always be capitalized.

Types of proper nouns include names of people and their

titles (e.g., Queen Elizabeth); names of ethnic groups,

national groups, and languages (e.g., Chinese); historical

events (e.g., Vietnam War); and geographical terms (e.g.,

Midwest). Note the capitalization of names and places in

this sentence from “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”:

“. . . there are two specialists here, Dr. Remington

from New York and Mr. Pritchard-Mitford from

London.”

READING AND THINKING

PRACTICE On your paper, rewrite the following paragraph. Capitalize each proper noun.

In one daydream, walter mitty becomes captain mitty.

The time is world war I, and the place is germany. Mitty

imagines he is flying against von richthofen, whom he

mistakenly calls von richtman, the famous aviator

known as the red baron.

APPLY Review a piece of your writing. List the proper

nouns and tell why each should be capitalized.

For more about capitalization, see Language

Handbook, p. R45.

• Sequence of Events

In stories, events often take place in chronological

sequence, or in the order in which they actually occur.

Sometimes, though, a writer uses flashbacks or other

devices to relate a story’s events out of chronological

sequence. In “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” Mitty’s daydreams transport him to another place and time. Thurber

uses ellipses and obvious clues as to the time and place

to signal changes in the sequence of events. Writers also

use verb tense and transition words or phrases, such as

before, earlier that morning, or once, to indicate shifts in

sequence.

VOCABULARY

• Capitalizing Proper Nouns

PRACTICE Find a passage in the story where Thurber

relates events out of chronological order without using

ellipses to signal the change. What words and phrases

help readers understand the order of events?

APPLY Review another story and analyze the way the

author ordered the events. Is the story told in strict

chronological order? Do characters describe events that

occurred in the past? Note how the author signals

changes in the sequence of events.

For more about reading strategies, see Reading

Handbook, pp. R78–R107.

• Synonyms

Synonyms are words that have the same or nearly the

same meaning. The words cheerful, delighted, glad,

pleased, joyous, and ecstatic are all synonyms for the

word happy. We need different words to describe one

emotion because that one emotion has many nuances, or

shades of meaning.

Paying attention to the differences that exist between

many synonyms will help you communicate more clearly

and better understand what you read. For example, insolent and sassy are synonyms, but they do not mean

exactly the same thing. A sassy remark may not be

respectful, but it is usually light and cheerful. An insolent

remark, on the other hand, is extremely rude and deliberately insulting.

PRACTICE For each word given, choose the synonym

that best matches its precise meaning.

1. craven

a. hesitant

b. spineless

2. pandemonium

a. riot

b. disturbance

3. disdainful

a. haughty

b. proud

4. distraught

a. bewildered

b. distracted

5. haggard

a. tired

b. drained

THE SHORT STORY

123

Avoiding Run-on Sentences

When people “run on” in conversation, they talk too long without pausing or stopping. A

run-on sentence has the same problem; it “runs on” instead of pausing or stopping where it

should. You can spot a run-on sentence by noticing main clauses—groups of words that have

both a subject and a verb and can function as sentences.

Main clauses must always be separated from each other with an end mark of punctuation,

with a semicolon, or with a comma and a coordinating conjunction.

Problem 1 A comma splice, or two main clauses separated only by a comma

Walter Mitty’s daydreams are funny, they are also interesting.

Solution A Replace the comma with an end mark of punctuation, such as a period or

a question mark, and begin the new sentence with a capital letter.

Walter Mitty’s daydreams are funny. They are also interesting.

Solution B Place a semicolon between the two main clauses.

Walter Mitty’s daydreams are funny; they are also interesting.

Solution C Add a coordinating conjunction after the comma.

Walter Mitty’s daydreams are funny, but they are also interesting.

Problem 2 Two main clauses with no punctuation between them

Mitty hated his weekly trips into town he always forgot something.

Solution A Separate the main clauses with an end mark of punctuation, such as a

period or question mark, and begin the second sentence with a capital letter.

Mitty hated his weekly trips into town. He always forgot something.

Solution B Separate the main clauses with a semicolon.

Mitty hated his weekly trips into town; he always forgot something.

Solution C Add a comma and a coordinating conjunction between the main clauses.

Mitty hated his weekly trips into town, and he always forgot something.

For more about run-on sentences, see Language Handbook, p. R15.

EXERCISE

Correct the run-on sentences below as you rewrite them

on your own paper. Apply the strategies shown above.

3. Walter Mitty wakes from his dreams noises from the

street rouse him.

1. Everyone has daydreams, few of us have daydreams

as detailed as Mitty’s.

4. Walter Mitty imagines himself to be a surgeon, he

also dreams he’s a pilot.

2. Reality is too dull for Mitty he escapes into his

imagination.

5. I know how Mitty feels I also daydream when someone is yelling at me.

124

UNIT 1

Web Site

Have you ever seen an unfamiliar

insect and said, “Eeeeew, what’s that?”

If you’re interested in entomology, the

study of insects, you’ll find lots of

information on the World Wide Web.

Mystery Bugs

Address:

www.uky.edu

Can you identify the mystery bugs? We now offer two categories of mystery pictures: Novice

and Expert. Try your hand at guessing the names of these insects!

Novice

Expert

(Text Hint)

(Text Hint)

Mystery Picture Hint: Novice

This arthropod is a pest to domestic

animals and humans. It is an external parasite that feeds on blood. It

has a broadly oval, unsegmented

body and eight short legs. After it

has fed it can balloon up to twelve

times its normal weight. It is the

primary vector of Rocky Mountain

Spotted Fever.

Mystery Picture Hint: Expert

These tiny wingless insects have distinctive heads

and a hump-backed appearance. Their name

comes from a forked structure attached to the

underside of the abdomen which acts as a spring

to flip them into the air. This behavior gives them

the appearance of tiny fleas. They live in rich soil or

leaf litter, under bark or decaying wood, or associated with fungi. Many are scavengers, feeding on

decaying plants, fungi, molds, or algae.

Send a message with your best guess(es) to our mailbox by clicking here.

Past Mysteries

Look here for a list of mystery pictures from the first to the most recent!

University of Kentucky Department of Entomology

Return to UK Department of Entomology Youthfacts

Return to UK Department of Entomology homepage

Analyzing Media

The photographs of these insects

have been enlarged many times.

How does seeing them so large—

and with so much detail—affect

your understanding of them?

Before You Read

Gaston

Reading Focus

How do you feel about insects? Think about cockroaches, ladybugs,

mosquitoes, butterflies, and ants. Do you feel the same way about

all insects?

Sharing Ideas Consider why you feel the way you do about particular insects and share your reasons with your classmates. Which

insects do people have different opinions about? Did your attitude

about a particular insect change after hearing other people’s opinions?

Setting a Purpose Read to learn about a father’s and daughter’s reactions to an insect.

Building Background

The Time and Place

The events in “Gaston” take place in Paris, France, one hot afternoon in

August, sometime in the 1950s or early 1960s.

Did You Know?

Did you ever see a cat investigating a new room and think that it was

curious about its surroundings? Attributing human qualities and characteristics to animals or inanimate objects is called anthropomorphism.

People frequently anthropomorphize animals or things so that they can

better relate to them. You anthropomorphize a lion if you say that it is

brave. You anthropomorphize your computer if you say that it is smart.

Vocabulary Preview

kilo (kē lō) n. short for kilogram, a unit of measure in the metric

system equal to 1,000 grams (about 2.2 pounds); p. 127

flawed (flod) adj. faulty; imperfect;

blemished; p. 127

precisely (pri s¯slē) adv. exactly; p. 128

Meet

William Saroyan

Like the man in this story,

William Saroyan (sə roiən) had

a huge mustache and a vivid

imagination. After his divorce,

he moved to Paris, France, where

his children visited him often.

Saroyan wrote stories, plays, novels, memoirs, and songs. The

dialogue and emotions of his

characters are very realistic, perhaps because much of his work

is based on his own experiences.

His play The Time of Your Life

won two major awards, including

the prestigious Pulitzer Prize.

Saroyan turned the prize down,

though, believing its donors were

not qualified to judge art.

William Saroyan was born in 1908 and

died in 1981. “Gaston” was first

published in the Atlantic Monthly in

February 1962.

Wi l l i a m S a r o y a n

THEY WERE TO EAT PEACHES, as

planned, after her nap, and now she sat across

from the man who would have been a total

stranger except that he was in fact her father.

They had been together again (although she

couldn’t quite remember when they had been

together before) for almost a hundred years

now, or was it only since day before yesterday?

Anyhow, they were together again, and he

was kind of funny. First, he had the biggest

mustache she had ever seen on anybody,

although to her it was not a mustache at all;

it was a lot of red and brown hair under his

nose and around the ends of his mouth.

Second, he wore a blue-and-white striped

jersey1 instead of a shirt and tie, and no coat.

His arms were covered with the same hair,

only it was a little lighter and thinner. He

wore blue slacks, but no shoes and socks.

He was barefoot, and so was she, of course.

He was at home. She was with him in his

home in Paris, if you could call it a home.

1. A jersey is a sweater or shirt, usually a close-fitting pullover,

made of machine-knitted fabric.

He was very old, especially for a young

man—thirty-six, he had told her; and she

was six, just up from sleep on a very hot

afternoon in August.

That morning, on a little walk in the

neighborhood, she had seen peaches in a

box outside a small store and she had

stopped to look at them, so he had bought

a kilo.

Now, the peaches were on a large plate on

the card table at which they sat.

There were seven of them, but one of

them was flawed. It looked as good as the

others, almost the size of a tennis ball, nice

red fading to light green, but where the stem

had been there was now a break that went

straight down into the heart of the seed.

He placed the biggest and best-looking

peach on the small plate in front of the girl,

and then took the flawed peach and began

to remove the skin. When he had half the

skin off the peach he ate that side, neither

of them talking, both of them just being

there, and not being excited or anything—

no plans, that is.

Vocabulary

kilo (kē lō) n. short for kilogram, a unit of measure in the metric system equal to 1,000

grams (about 2.2 pounds)

flawed (flod) adj. faulty; imperfect; blemished

THE SHORT STORY

127

The creature paused only a fraction of a second and then continued

to come out of the seed, to walk

down the eaten side of the peach to

wherever it was going.

The girl had never seen anything like it—a whole big thing

made out of brown color, a knobhead, feelers, and a great many legs.

It was very active, too. Almost businesslike, you might say. The man

placed the peach back on the plate.

The creature moved off the peach

onto the surface of the white plate.

There it came to a thoughtful stop.

“Who is it?” the girl said.

“Gaston.”2

“Where does he live?”

“Well, he used to live in this

peach seed, but now that the peach

has been harvested and sold, and I

have eaten half of it, it looks as if

he’s out of house and home.”

The Pink Bow. Alice Beach Winter (1877–1970). Oil on canvas, 24 x 20 in. Private

“Aren’t you going to squash him?”

collection.

“No, of course not, why should I?”

Viewing the painting: What might this child have in common with the little

“He’s a bug. He’s ugh.”

girl in the story?

“Not at all. He’s Gaston the

grand boulevardier.”3

“Everybody hollers when a bug comes out

The man held the half-eaten peach in his

of an apple, but you don’t holler or anything.”

fingers and looked down into the cavity, into

“Of course not. How would we like it if

the open seed. The girl looked, too.

somebody hollered every time we came out of

While they were looking, two feelers

our house?”

poked out from the cavity. They were

“Why would they?”

attached to a kind of brown knob-head,

“Precisely. So why should we holler at

which followed the feelers, and then two

Gaston?”

large legs took a strong grip on the edge of

“He’s not the same as us.”

the cavity and hoisted some of the rest of

whatever it was out of the seed, and stopped

2. Gaston (as t o n)

there a moment, as if to look around.

3. Here, boulevardier (boo

¯¯¯ l var dyā) is a man about town,

The man studied the seed dweller, and so,

a worldly person who frequently goes to fancy restaurants

of course, did the girl.

and clubs, mainly in an effort to be seen.

Vocabulary

128

precisely (pri s¯slē) adv. exactly

UNIT 1

Wi l l i a m S a r o y a n

“Well, not exactly, but he’s the same as a

lot of other occupants of peach seeds. Now,

the poor fellow hasn’t got a home, and there

he is with all that pure design and handsome

form, and nowhere to go.”

“Handsome?”

“Gaston is just about the handsomest of

his kind I’ve ever seen.”

“What’s he saying?”

“Well, he’s a little confused. Now, inside

that house of his he had everything in order.

Bed here, porch there, and so forth.”

“Show me.”

The man picked up the peach, leaving

Gaston entirely alone on the white plate. He

removed the peeling and ate the rest of the

peach.

“Nobody else I know would do that,” the

girl said. “They’d throw it away.”

“I can’t imagine why. It’s a perfectly good

peach.”

He opened the seed and placed the two

sides not far from Gaston. The girl studied

the open halves.

“Is that where he lives?”

“It’s where he used to live. Gaston is out

in the world and on his own now. You can see

for yourself how comfortable he was in there.

He had everything.”

“Now what has he got?”

“Not very much, I’m afraid.”

“What’s he going to do?”

“What are we going to do?”

“Well, we’re not going to squash him, that’s

one thing we’re not going to do,” the girl said.

“What are we going to do, then?”

“Put him back?”

“Oh, that house is finished.”

“Well, he can’t live in our house, can he?”

“Not happily.”

“Can he live in our house at all?”

“Well, he could try, I suppose. Don’t you

want to eat a peach?”

“Only if it’s a peach with somebody in the

seed.”

“Well, see if you can find a peach that has

an opening at the top, because if you can,

that’ll be a peach in which you’re likeliest to

find somebody.”

The girl examined each of the peaches on

the big plate.

“They’re all shut,” she said.

“Well, eat one, then.”

“No. I want the same kind that you ate,

with somebody in the seed.”

“Well, to tell you the truth, the peach I

ate would be considered a bad peach, so of

course stores don’t like to sell them. I was

sold that one by mistake, most likely. And so

now Gaston is without a home, and we’ve got

six perfect peaches to eat.”

“I don’t want a perfect peach. I want a

peach with people.”

“Well, I’ll go out and see if I can find one.”

“Where will I go?”

“You’ll go with me, unless you’d rather

stay. I’ll only be five minutes.”

“If the phone rings, what shall I say?”

“I don’t think it’ll ring, but if it does, say

hello and see who it is.”

“If it’s my mother, what shall I say?”

“Tell her I’ve gone to get you a bad peach,

and anything else you want to tell her.”

“If she wants me to go back, what shall I

say?”

“Say yes if you want to go back.”

“Do you want me to?”

“Of course not, but the important thing is

what you want, not what I want.”

“Why is that the important thing?”

“Because I want you to be where you want

to be.”

“I want to be here.”

“I’ll be right back.”

He put on socks and shoes, and a jacket,

and went out. She watched Gaston trying to

THE SHORT STORY

129

find out what to do next. Gaston wandered

around the plate, but everything seemed wrong

and he didn’t know what to do or where to go.

The telephone rang and her mother said

she was sending the chauffeur to pick her up

because there was a little party for somebody’s

daughter who was also six, and then tomorrow they would fly back to New York.

“Let me speak to your father,” she said.

“He’s gone to get a peach.”

“One peach?”

“One with people.”

“You haven’t been with your father two

days and already you sound like him.”

“There are peaches with people in them. I

know. I saw one of them come out.”

“A bug?”

“Not a bug. Gaston.”

“Who?”

“Gaston the grand something.”

“Somebody else gets a peach with a bug in

it, and throws it away, but not him. He makes

up a lot of foolishness about it.”

“It’s not foolishness.”

“All right, all right, don’t get angry at me

about a horrible peach bug of some kind.”

“Gaston is right here, just outside his broken house, and I’m not angry at you.”

Peaches and Almonds, 1901. Auguste Renoir. Oil on canvas, 31.1 x 41.3 cm. Tate Gallery, London.

Viewing the painting: In your opinion, would these peaches satisfy the little girl in the story?

Why or why not?

130

UNIT 1

Wi l l i a m S a r o y a n

“You’ll have a lot of fun at the party.”

“OK.”

“We’ll have fun flying back to New York,

too.”

“OK.”

“Are you glad you saw your father?”

“Of course I am.”

“Is he funny?”

“Yes.”

“Is he crazy?”

“Yes. I mean, no. He just doesn’t holler

when he sees a bug crawling out of a peach

seed or anything. He just looks at it carefully.

But it is just a bug, isn’t it, really?”

“That’s all it is.”

“And we’ll have to squash it?”

“That’s right. I can’t wait to see you, darling. These two days have been like two years

to me. Good-bye.”

The girl watched Gaston on the plate, and

she actually didn’t like him. He was all ugh, as

he had been in the first place. He didn’t have

a home anymore and he was wandering around

on the white plate and he was silly and wrong

and ridiculous and useless and all sorts of other

things. She cried a little, but only inside,

because long ago she had decided she didn’t

like crying because if you ever started to cry it

seemed as if there was so much to cry about

you almost couldn’t stop, and she didn’t like

that at all. The open halves of the peach seed

were wrong, too. They were ugly or something.

They weren’t clean.

The man bought a kilo of peaches but

found no flawed peaches among them, so he

bought another kilo at another store, and this

time his luck was better, and there were two

that were flawed. He hurried back to his flat

and let himself in.

His daughter was in her room, in her best

dress.

“My mother phoned,” she said, “and she’s

sending the chauffeur for me because there’s

another birthday party.”

“Another?”

“I mean, there’s always a lot of them in

New York.”

“Will the chauffeur bring you back?”

“No. We’re flying back to New York

tomorrow.”

“Oh.”

“I liked being in your house.”

“I liked having you here.”

“Why do you live here?”

“This is my home.”

“It’s nice, but it’s a lot different from our

home.”

“Yes, I suppose it is.”

“It’s kind of like Gaston’s house.”

“Where is Gaston?”

“I squashed him.”

“Really? Why?”

“Everybody squashes bugs and worms.”

“Oh. Well. I found you a peach.”

“I don’t want a peach anymore.”

“OK.”

He got her dressed, and he was packing

her stuff when the chauffeur arrived. He went

down the three flights of stairs with his

daughter and the chauffeur, and in the street

he was about to hug the girl when he decided

he had better not. They shook hands instead,

as if they were strangers.

He watched the huge car drive off, and

then he went around the corner where

he took his coffee every morning, feeling a

little, he thought, like Gaston on the

white plate.

THE SHORT STORY

131

Active Reading and Critical Thinking

Responding to Literature

Personal Response

Would you have done what the girl did to Gaston at the end of the story?

Explain why or why not.

Literary

ELEMENTS

Analyzing Literature

Exposition

Recall

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Describe the setting of the story.

Who is Gaston? What does he look like?

Why wouldn’t the girl eat any of the peaches?

What did the girl do after she talked to her mother on the phone?

How did the girl and her father say good-bye?

Interpret

6. What are some differences you can infer between the girl’s usual

home and that of her father?

7. In what way was the father’s reaction to Gaston unusual? What does

this suggest about him?

8. Why does the girl’s attitude toward Gaston keep changing?

9. According to the narrator, the little girl no longer cried out loud

because she thought that “if you ever started to cry it seemed as if

there was so much to cry about you almost couldn’t stop.” What does

this statement imply about the little girl’s frame of mind and her feelings about her family life?

10. What do you learn about the father from the way the story ends?

Evaluate and Connect

11. On the phone, the mother tells the girl that her father’s story about

Gaston is foolishness. Do you agree or disagree with the mother’s

assessment? Explain.

12. Do you think both parents are good parents? Support your answer

with evidence from the story.

13. Think about your response to the Reading Focus on page 126. Has this

story’s use of anthropomorphism changed your point of view in any

way? Explain.

14. Evaluate Saroyan’s use of dialogue, or conversation between characters, in this story. How does the dialogue help you get to know the

characters?

15. Theme Connections How would you describe the void that exists in

each of the three characters’ lives?

132

UNIT 1

Exposition is the introduction of the

characters, the setting, or the situation

at the beginning of a story. The details

a writer chooses to include in the first

few paragraphs are important, because

they set the tone for the rest of the

work. For example, in the first paragraph Saroyan describes the father as

a “man who would have been a total

stranger except that he was in fact her

father.” This statement gives readers

an early insight into the relationship

between the man and his daughter.

1. What do you learn about the two

main characters in the first sentence

of the story?

2. What are the first details you know

about the father? What can you

infer about him from these details?

3. What do you learn about the setting

in the second paragraph?

• See Literary Terms Handbook,

p. R5.

Literary Criticism

According to one critic, “Saroyan’s work

conveys a powerful sense of not being at

home in the world.” With a partner, discuss

whether you think this sense is conveyed

in “Gaston.”

Literature and Writing

Writing About Literature

Creative Writing

Making Comparisons The story ends with this sentence

about the father: “He watched the huge car drive off, and

then he went around the corner where he took his coffee

every morning, feeling a little, he thought, like Gaston on

the white plate.” In what ways is the father like Gaston?

Write a comparison using details from the story to support

your ideas.

You’re Invited Compose a note that the father in this

story might write to his daughter, in which he invites her

to Paris for another visit. In order to persuade her to make

the trip, remind her of how fun the last visit was and how

good it felt to get to know her. You may even want to suggest how the next visit might be different. In your writing,

try to mimic the way the man speaks in the story.

Extending Your Response

Literature Groups

Internet Connection

You Be the Judge Imagine that a judge is determining

whether the mother or the father will have full custody of

the little girl or whether they will have joint custody. Using

details from the story to support your opinion, argue for

one of the three options. Try to reach an agreement on

where—and with whom—the girl should live.

The City of Lights Many writers and artists have been

attracted to Paris. Search the Internet for information

about Paris and its art community. First, look at travel

sites for general information. Then, narrow your search

to Web pages of Parisian art museums, cultural centers,

or theaters. Report your findings to the class.

Interdisciplinary Activity

Reading Further

Biology: Going Buggy Choose an insect to research and

prepare a brief report of your findings. In your report,

describe your subject, identify its habitat, and discuss its

impact on humans. Include a sketch or photo as a visual

aid. You may want to begin your research on the Internet,

looking for sites about your particular insect.

You might enjoy these works by William Saroyan:

Novel: The Human Comedy tells about a young boy

determined to become the fastest messenger in the West

during World War II.

Story: “Mystic Games,” from the book Madness in the

Family, tells about a boy who outwits his uncle.

Save your work for your portfolio.

VOCABULARY

SkillMinilesson

• Clipped Words

Many English words are short forms of longer words;

for example, kilo is short for either kilogram or kilometer. (To know which meaning kilo has, you need to

consider the context.) The long form of some clipped

words, such as bike, gas, exam, and lab, may be just

as familiar as the short form. Some long forms are

less familiar; van, for example, was shortened from

caravan. Pants comes from the word pantaloons.

PRACTICE Match each clipped word in the left

column with its original form in the right column.

1. flu

a. curiosity

2. wig

b. gabble

3. curio

c. influenza

4. sport

d. periwig

5. gab

e. disport

THE SHORT STORY

133

Before You Read

And Sarah Laughed

Reading Focus

Which would be more of a challenge, living with someone who was

unable to hear or living with someone who was unwilling to listen?

Quickwrite Spend ten minutes writing an answer to the

question above.

Setting a Purpose Read to learn about how a person who can

hear becomes a person who can listen.

Building Background

The Time and Place

The story is set in a small rural community, possibly in the Midwest, in

the early to mid-1900s.

Did You Know?

Today, American Sign Language, or ASL, is the fourth most-used language in the United States. It consists of hand signs representing words

or phrases and a manual alphabet used to spell out words or names

that have no sign. At the time of this story, few people used sign language. Throughout most of the twentieth century, deaf children were

taught to speak and to read lips. It was mistakenly thought that using

sign language would set the deaf apart from their peers and alienate

children from their hearing parents. As a result, communication

between deaf and hearing people was sometimes very difficult. In the

1960s, however, American Sign Language became more accepted, and

today it is offered as a course of study in some high schools and colleges. Rather than separating deaf people from hearing people, ASL has

improved communication between the two groups.

Vocabulary Preview

reticence (retə səns) n. the tendency to keep one’s thoughts and

feelings to oneself; p. 136

strident (str¯dənt) adj. loud, harsh, and shrill; p. 139

inflection (in flekshən) n. change or variation in the tone or pitch of

the voice; p. 140

anguish (anwish) n. extreme mental or emotional suffering; p. 143

vindictive (vin diktiv) adj. wanting revenge; p. 144

134

UNIT 1

Meet

Joanne Greenberg

ambition in life is to keep

“onMywriting,

getting better all the

time, until I hit eighty-five, and

then coast.

”

Joanne Greenberg grew up in

Brooklyn, New York, and later

moved to Manhattan. In spite of

the city’s dense population and its

cultural diversity, Greenberg felt

isolated. The theme of isolation is

apparent in much of her work,

including the novel I Never

Promised You a Rose Garden, which

she wrote under the pseudonym

Hannah Green. Greenberg—a

wife, mother, and interpreter for

the deaf—is the author of many

acclaimed short stories and novels.

Joanne Greenberg was born in 1932.

“And Sarah Laughed” was published in

Rites of Passage in 1972.

Joanne Greenberg

HE WENT TO THE WINDOW EVERY FIFTEEN MINUTES to see if

they were coming. They would be taking the new highway cutoff; it would

bring them past the south side of the farm; past the unused, dilapidated outbuildings instead of the orchards and fields that were now full and green.

It would look like a poor place to the new

bride. Her first impression of their farm would

be of age and bleached-out, dried-out buildings on which the doors hung open like a row

of gaping mouths that said nothing.

All day, Sarah had gone about her work

clumsy with eagerness and hesitant with dread,

picking up utensils to forget them in holding,

finding them two minutes later a surprise in her

hand. She had been planning and working ever

since Abel wrote to them from Chicago that

he was coming home with a wife. Everything

should have been clean and orderly. She

wanted the bride to know as soon as she

walked inside what kind of woman Abel’s

mother was—to feel, without a word having to

be said, the house’s dignity, honesty, simplicity,

and love. But the spring cleaning had been

late, and Alma Yoder had gotten sick—Sarah

had had to go over to the Yoders and help out.

Now she looked around and saw that it

was no use trying to have everything ready in

time. Abel and his bride would be coming

any minute. If she didn’t want to get caught

shedding tears of frustration, she’d better get

herself under control. She stepped over the

pile of clothes still unsorted for the laundry

and went out on the back porch.

THE SHORT STORY

135

The sky was blue and silent, but as she

watched, a bird passed over the fields crying.

The garden spread

out before her, displaying its varying

greens. Beyond it,

along the creek,

there was a row of

poplars. It always

calmed her to look

at them. She

looked today. She

Did You Know?

and Matthew had

The poplar tree is in the willow

family and has pale, ridged bark

planted those trees.

and broad leaves. Often, rows of

They stood thirty

tall, dignified (stately) poplars are

feet high now,

grown as a windbreak.

stately as figures in

a procession. Once—only once and many

years ago—she had tried to describe in words

the sounds that the wind made as it combed

those trees on its way west. The little boy to

whom she had spoken was a grown man

now, and he was bringing home a wife.

Married. . . .

Ever since he had written to tell them he

was coming with his bride, Sarah had been

going back in her mind to the days when she

and Matthew were bride and groom and then

mother and father. Until now, it hadn’t

seemed so long ago. Her life had flowed on

past her, blurring the early days with Matthew

when this farm was strange and new to her

and when the silence of it was sharp and bitter like pain, not dulled and familiar like an

echo of old age.

Matthew hadn’t changed much. He was a

tall, lean man, but he had had a boy’s spareness then. She remembered how his smile

came, wavered and went uncertainly, but how

his eyes had never left her. He followed

everything with his eyes. Matthew had always

been a silent man; his face was expressionless

and his body stiff with reticence, but his eyes

had sought her out eagerly and held her and

she had been warm in his look.

Sarah and Matthew had always known

each other—their families had been neighbors. Sarah was a plain girl, a serious “decent”

girl. Not many of the young men asked her

out, and when Matthew did and did again,

her parents had been pleased. Her father told

her that Matthew was a good man, as steady

as any woman could want. He came from

honest, hard-working people and he would

prosper any farm he had. Her mother spoke

shyly of how his eyes woke when Sarah came

into the room, and how they followed her. If

she married him, her life would be full of the

things she knew and loved, an easy, familiar

world with her parents’ farm not two miles

down the road. But no one wanted to mention the one thing that worried Sarah: the

fact that Matthew was deaf. It was what

stopped her from saying yes right away; she

loved him, but she was worried about his

deafness. The things she feared about it were

the practical things: a fall or a fire when he

wouldn’t hear her cry for help. Only long

after she had put those fears aside and moved

the scant two miles into his different world,

did she realize that the things she had feared

were the wrong things.

Now they had been married for twentyfive years. It was a good marriage—good

enough. Matthew was generous, strong, and

loving. The farm prospered. His silence made

him seem more patient, and because she

became more silent also, their neighbors saw

in them the dignity and strength of two people who do not rail1 against misfortune, who

1. Rail means “to complain bitterly.”

Vocabulary

136

reticence (retə səns) n. the tendency to keep one’s thoughts and feelings to oneself

UNIT 1

River Fields, 1983. Walter Hatke. Oil on linen, 23¹⁄₂ x 38¹⁄₄ in. Collection of The Chase Manhattan Bank, New York.

Viewing the painting: How would you describe the mood of this painting? How well does the painting reflect

the mood of the story? Explain.

were beyond trivial talk and gossip; whose

lives needed no words. Over the years of help

given and meetings attended, people noticed

how little they needed to say. Only Sarah’s

friend Luita knew that in the beginning, when

they were first married, they had written

yearning notes to each other. But Luita didn’t

know that the notes also were mute. Sarah

had never shown them to anyone, although

she kept them all, and sometimes she would

go up and get the box out of her closet and

read them over. She had saved every scrap,

from questions about the eggs to the tattered

note he had left beside his plate on their first

anniversary. He had written it when she was

busy at the stove and then he’d gone out and

she hadn’t seen it until she cleared the table.

The note said: “I love you derest wife Sarah.

I pray you have happy day all day your life.”

When she wanted to tell him something,

she spoke to him slowly, facing him, and he

took the words as they formed on her lips. His

speaking voice was thick and hard to understand and he perceived that it was unpleasant.

He didn’t like to use it. When he had to say

something, he used his odd, grunting tone, and

she came to understand what he said. If she ever

hungered for laughter from him or the little

meaningless talk that confirms existence and

affection, she told herself angrily that Matthew

talked through his work. Words die in the air;

they can be turned one way or another, but

Matthew’s work prayed and laughed for him.

He took good care of her and the boys, and

they idolized him. Surely that counted more

than all the words—words that meant and

didn’t mean—behind which people could hide.

Over the years she seldom noticed her

own increasing silence, and there were times

when his tenderness, which was always given

without words, seemed to her to make his

silence beautiful.

THE SHORT STORY

137

She thought of the morning she had come

downstairs feeling heavy and off balance with

her first pregnancy—with Abel. She had gone

to the kitchen to begin the day, taking the

coffeepot down and beginning to fill it when

her eye caught something on the kitchen

table. For a minute she looked around in

confusion. They had already laid away what

the baby would need: diapers, little shirts

and bedding, all folded away in the drawer

upstairs, but here on the table was a bounty

of cloth, all planned and scrimped for and

bought from careful, careful study of the catalogue—yards of patterned flannel and plissé,2

coat wool and bright red corduroy. Sixteen

yards of yellow ribbon for bindings. Under the

coat wool was cloth Matthew had chosen for

her; blue with a little gray figure. It was silk,

and there was a card on which was rolled precisely enough lace edging for her collar and

sleeves. All the long studying and careful

planning, all in silence.

She had run upstairs and thanked him

and hugged him, but it was no use showing

delight with words, making plans, matching

cloth and figuring which pieces would be for

the jacket and which for sleepers. Most wives

used such fussing to tell their husbands how

much they thought of their gifts. But

Matthew’s silence was her silence too.

hen he had left to go to the

orchard after breakfast that

morning, she had gone to

their room and stuffed her ears with cotton,

trying to understand the world as it must be

to him, with no sound. The cotton dulled the

outside noises a little, but it only magnified

all the noises in her head. Scratching her

cheek caused a roar like a downpour of rain;

her own voice was like thunder. She knew

Matthew could not hear his own voice in his

2. Plissé (pli sā) is a cotton fabric with a crinkly finish.

138

UNIT 1

head. She could not be deaf as he was deaf.

She could not know such silence ever.

So she found herself talking to the baby

inside her, telling it the things she would

have told Matthew, the idle daily things:

Didn’t Margaret Amson look peaked3 in

town? Wasn’t it a shame the drugstore had

stopped stocking lump alum4—her pickles

wouldn’t be the same.

Abel was a good baby. He had Matthew’s

great eyes and gentle ways. She chattered to

him all day, looking forward to his growing

up, when there would be confidences

between them. She looked to the time when

he would have his own picture of the world,

and with that keen hunger and hope she had

a kind of late blooming into a beauty that

made people in town turn to look at her

when she passed in the street holding the

baby in the fine clothes she had made for

him. She took Abel everywhere, and came

to know a pride that was very new to her,

a plain girl from a modest family who had

married a neighbor boy. When they went

to town, they always stopped over to see

Matthew’s parents and her mother.

Mama had moved to town after Pa died. Of

course they had offered to have Mama come

and live with them, but Sarah was glad she

had gone to a little place in town, living where

there were people she knew and things happening right outside her door. Sarah remembered them visiting on a certain spring day, all

sitting in Mama’s new front room. They sat

uncomfortably in the genteel5 chairs, and Abel

crawled around on the floor as the women

talked, looking up every now and then for his

father’s nod of approval. After a while he went

to catch the sunlight that was glancing off a

3. Margaret Amson looked pale and sickly (peaked).

4. Alum (al əm) is a chemical compound that is used to purify

water and stop bleeding as well as in pickle-making.

5. Here, genteel means “elegant; stylish.”

Joanne Greenberg

crystal nut dish and scattering rainbow bands

on the floor. Sarah smiled down at him. She

too had a radiance, and, for the first time in

her life, she knew it. She was wearing the dress

she had made from Matthew’s cloth—it

became her and she knew that too, so she gave

her joy freely as she traded news with Mama.

Suddenly they heard the fire bell ringing

up on the hill. She caught Matthew’s eye and

mouthed, “Fire engines,” pointing uphill to

the firehouse. He nodded.

In the next minutes there was the strident,

off-key blare as every single one of Arcadia’s

volunteer firemen—his car horn plugged with

a matchstick and his duty before him—drove

hellbent for the firehouse in an ecstasy of bell

and siren. In a minute the ding-ding-ding-ding

careened in deafening, happy privilege

through every red light in town.

“Big bunch of boys!” Mama laughed. “You

can count two Saturdays in good weather

when they don’t have a fire, and that’s during

the hunting season!”

They laughed. Then Sarah looked down

at Abel, who was still trying to catch the

wonderful colors. A madhouse of bells, horns,

screaming sirens

had gone right past

them and he hadn’t

cried, he hadn’t

looked, he hadn’t

turned. Sarah

twisted her head

sharply away and

screamed to the

Did You Know?

china cats on the

A whatnot shelf is an open

whatnot shelf as

shelf for displaying trinkets

and ornaments.

loud as she could,

but Abel’s eyes only

flickered to the movement and then went

back to the sun and its colors.

Mama whispered, “Oh, my dear God!”

Sarah began to cry bitterly, uncontrollably,

while her husband and son looked on, confused, embarrassed, unknowing.

he silence drew itself over the seasons and the seasons layered into

years. Abel was a good boy;

Matthew was a good man.

Later, Rutherford, Lindsay, and Franklin

Delano came. They too were silent. Hereditary nerve deafness was rare, the doctors

all said. The boys might marry and produce

deaf children, but it was not likely. When

they started to school, the administrators

and teachers told her that the boys would be

taught specially to read lips and to speak.

They would not be “abnormal,” she was told.

Nothing would show their handicap, and

with training no one need know that they

were deaf. But the boys seldom used their

lifeless voices to call to their friends; they

seldom joined games unless they were forced

to join. No one but their mother understood

their speech. No teacher could stop all the

jumping, turning, gum-chewing schoolboys,

or remember herself to face front from the

blackboard to the sound-closed boys. The

lip-reading exercises never seemed to make

plain differences—“man,” “pan,” “began.”

But the boys had work and pride in the

farm. The seasons varied their silence with

colors—crows flocked in the snowy fields in

winter, and tones of golden wheat darkened

across acres of summer wind. If the boys

couldn’t hear the bedsheets flapping on the

washline, they could see and feel the autumn

day. There were chores and holidays and the

wheel of birth and planting, hunting, fishing,

and harvest. The boys were familiar in town;

nobody ever laughed at them, and when

Vocabulary

strident (str¯dənt) adj. loud, harsh, and shrill

THE SHORT STORY

139

Sarah wanted to cry to

these kindly women that the

simple orders the boys

obeyed by reading her lips

were not a miracle. If she

could ever hear in their

long-practiced robot voices a

question that had to do with

feelings and not facts, and

answer it in words that rose

beyond the daily, tangible

things done or not done, that

would be a miracle.

Her neighbors didn’t

know that they themselves

confided to one another

from a universe of hopes, a

world they wanted half lost

in the world that was; how

often they spoke pitting

inflection against meaning

to soften it, harden it, make

a joke of it, curse by it, bless

by it. They didn’t realize

how they wrapped the bare

words of love in gentle

humor or wild insults that

the loved ones knew were

ways of keeping the secret of

love between the speaker

and the hearer. Mothers lovEdith Holman Hunt, 1876. William Holman Hunt. Red and black chalk on paper,

ingly called their children

54.3 x 37.4 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

crow-bait, mouse-meat, devViewing the art: What personal qualities or characteristics does this woman seem to

ils. They predicted dark ends

possess? Which of these qualities might Sarah possess?

for them, and the children

heard the secrets beneath

the words, heard them and smiled and knew,

Sarah met neighbors at the store, they praised

and let the love said-unsaid caress their

her sons with exaggerated praise, well meant,

souls. With her own bitter knowledge Sarah

saying that no one could tell, no one could

could only thank them for well-meaning and

really tell unless they knew, about the boys

return to silence.

not hearing.

Vocabulary

140

inflection (in flekshən) n. change or variation in the tone or pitch of the voice

UNIT 1