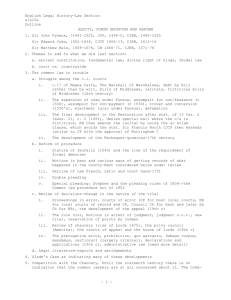

orientation materials - Gonzaga University School of Law

advertisement