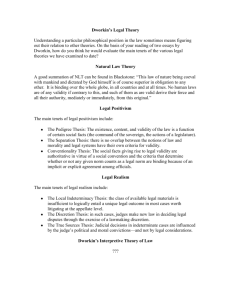

Explaining Theoretical Disagreement

advertisement