The

BIG

Question

Randy Faris/CORBIS

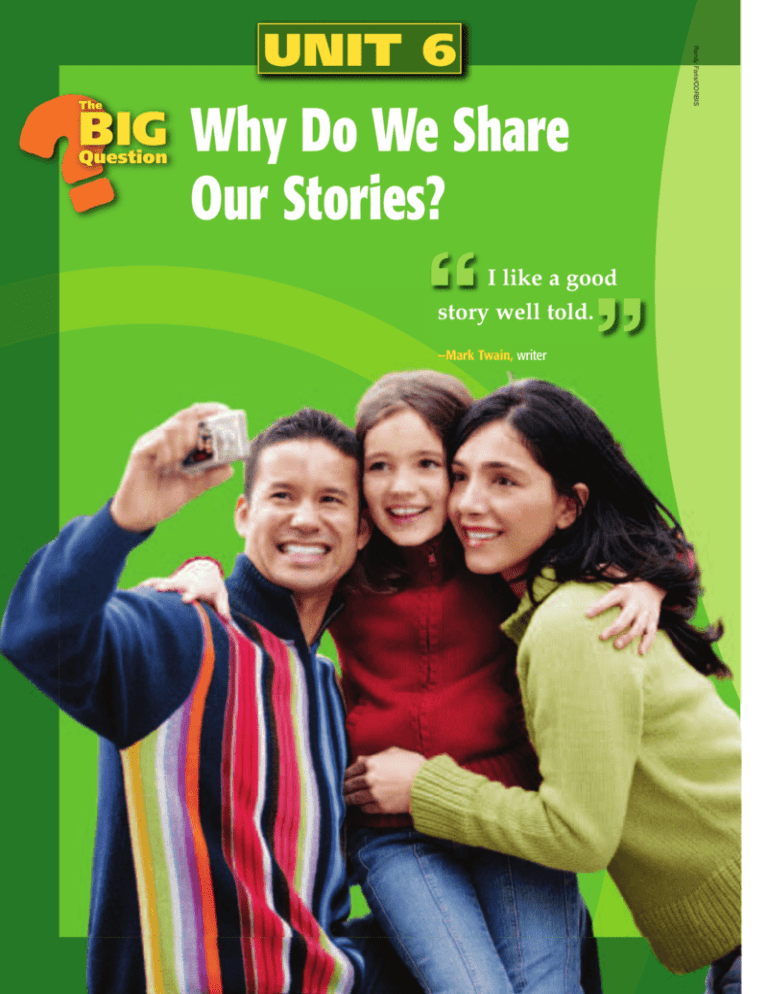

UNIT 6

2

Why Do We Share

Our Stories?

“

I like a good

story well told.

—Mark Twain, writer

”

LOOKING AHEAD

The skill lessons and readings in this unit will help you develop your own answer

to the Big Question.

UNIT 6 WARM-UP • Connecting to the Big Question

GENRE FOCUS: Folktale

Brer Rabbit and Brer Lion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 654

by Julius Lester

READING WORKSHOP 1

Skill Lesson: Understanding Cause

and Effect

The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 660

by Phyllis Savory

Charles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 668

by Shirley Jackson

WRITING WORKSHOP PART 1

Modern Folktale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 676

READING WORKSHOP 2

Skill Lesson: Questioning

The Boy and His Grandfather . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 684

by Rudolfo A. Anaya

Jeremiah’s Song . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 690

by Walter Dean Myers

READING WORKSHOP 3

Skill Lesson: Predicting

The Tale of ‘Kiko-Wiko . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 706

by Mark Crilley

We Are All One. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 716

by Laurence Yep

WRITING WORKSHOP PART 2

Modern Folktale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 724

READING WORKSHOP 4

Skill Lesson: Analyzing

Voices—and Stories—from the Past . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 734

by Kathryn Satterfield, updated from Time for Kids

Aunty Misery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 742

by Judith Ortiz Cofer

COMPARING LITERATURE WORKSHOP

Comparing

Cultural Contexts

Aunt Sue’s Stories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 751

by Langston Hughes

I Ask My Mother to Sing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 753

by Li-Young Lee

UNIT 6 WRAP-UP • Answering the Big Question

649

UNIT 6

WARM-UP

Connecting to

Why Do We Share

Our Stories?

We share our stories for many reasons—sometimes just for fun. For example, you and your

friends may have entertained each other with funny stories about school or your lives. We also

share our stories to keep the past alive and preserve our memories. In your own life, your family may have shared stories with you about what you were like as a little kid. Through storytelling, we can even share words of wisdom and comfort. In this unit, you’ll read stories and

poems that will help you explore these and other reasons that we share our stories.

Real Kids and the Big Question

Lannette has been very quiet. Her friends are worried. Her parents divorced six months ago, but Lannette has never talked

about it. Her friend, ANA, wants to help. She remembers

when her parents divorced and has some idea of how Lannette

is feeling. Ana wants to share her experiences with Lannette. Do

you think she should? Why or why not?

ROBERT’S new stepsister, Cleo,

has been getting into trouble at

school. Robert was a troublemaker himself when he was

Cleo’s age. But after getting

expelled from school four

years ago, he turned his

life around. Now Robert

is a “B” student and a lot

happier. He’s thinking of

sharing his story with

Cleo. Do you think

Cleo can learn from

Robert’s experiences?

Warm-Up Activity

With other students, talk about what you think Ana and Robert

should do and why.

650 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

(l)Think Stock/Getty Images, (r)CORBIS

UNIT 6 WARM-UP

You and the Big Question

Reading different stories and poems will help you figure out your

own answer to the Big Question.

Plan for the Unit Challenge

At the end of the unit, you’ll use notes from all your reading to

complete the Unit Challenge. The Challenge will help you explore

your answer to the Big Question.

Big Question Link to Web

resources to further explore

the Big Question at www

.glencoe.com.

You will choose one of the following activities:

A. Sharing-Stories Reading List You’ll work with classmates to make a list of

stories you think other students your age would enjoy.

B. Story Review You’ll choose a story you’ve read and explain why you think it

is or is not worth sharing.

• Start thinking about which activity you’d like to do so that you can focus your

thinking as you go through the unit.

• In your Learner’s Notebook, write about which you like better—working by

yourself or working with other students. That may help you decide which activity you’d like to do.

• Remember to take notes about possible answers to the Big Question.

Your notes will help you do the Unit Challenge activity you choose.

Keep Track of Your Ideas

As you read, you’ll make notes about the Big Question. Later, you’ll use

these notes to complete the Unit Challenge. See page R8 for help with

making Foldable 6. This diagram shows how one side of it should look.

1. Use this Foldable for all of the selections in

this unit. Label each “tab” with a title. (See

page 649 for the titles.) You should be able

to see all the titles without opening the

Foldable.

2. Below each title, write My Purpose for

Reading.

3. Further below each title, a third of

the way down the page, write the

label The Big Question.

Warm-Up 651

UNIT 6 GENRE FOCUS: FOLKTALE

A folktale is a story that was told by generations of storytellers before it

was ever written down. We don’t know the names of all those storytellers.

Some were professionals who told tales as entertainment. Some were teachers who used folktales to teach important lessons. Some were mothers and

fathers who told stories to their children, just as parents still do.

Skillss Focus

• Keyy skills for reading

fol

olktales

ol

•K

Key literary elements of

folktales

SSkills Model

You will see how to use the

key reading skills and literary

elements as you read

• Brer Rabbit and Brer Lion,

p. 654

Folktales belong to a category called folklore. This more general term

includes songs, speeches, sayings, and even jokes. In this unit, you’ll read

several forms of folklore.

• Trickster tale—a story in which a character, often an animal, outsmarts

an enemy. An example of a trickster character is Brer Rabbit in the story

you’ll read next.

• Origin story—a story about the origins, or beginnings, of something in

nature. In this unit, a story from Africa tells why the hyena has oddly long

hairs growing on its back. Other origin stories explain such things as how

tigers got their stripes and why the sky is blue.

• Fairy tale—a story with magical beings who change the lives of ordinary

people. The stories of Cinderella and Snow White—and their fairy godmothers—are fairy tales. One story in this unit features a magical being

who is definitely not Cinderella’s fairy godmother.

• Tall tale—a fantasy story about an amazing, larger-than-life person. At the

end of this unit, you’ll read one of the many American tall tales told

about Paul Bunyan.

• Legend—a story about an amazing event or a hero’s amazing accomplishment. Some legends are about people who actually lived, but over the

years their reputations grew “larger than life.”

• Myth—a story about gods and goddesses and how they were involved in

making things the way they are. Characters from ancient myths were

featured in two popular TV series in the 1990s—Hercules: The Legendary

Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess.

Two main things make all of these different forms alike. First, they were

passed down over many generations. Second, they still help members of a

culture to stay connected to one another.

Objectives

(pp. 652–655)

Reading Understand cause and

effect • Monitor comprehension:

ask questions • Make predictions

• Analyze text

Literature Identify literary elements: theme, character, cultural

context, dialect

Why Read Folktales?

Folktales are fun to read. The characters in them can make you smile and

laugh, but they can also make you stop and think. Folktales may also bring

back good memories. They’re the kinds of stories you heard and read when

you were little. Maybe most important of all, reading folktales can help you

understand why people share stories.

652 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

UNIT 6 GENRE FOCUS

How to Read Folktales

Key Reading Skills

These key reading skills are especially useful tools for reading and understanding folktales. You’ll learn more about these skills later in the unit.

■ Understanding Cause and Effect As you read, look for causes—the

reasons why things happen—and for effects—the things that happen as a

result. (See Reading Workshop 1.)

■ Questioning To make sure you understand what you’re reading, ask

yourself questions while you read. (See Reading Workshop 2.)

■ Predicting Guess what will happen next in a story to help yourself get

more involved in what you’re reading. (See Reading Workshop 3.)

■ Analyzing To understand a text better, think about its parts and how

they work together to make meaning. (See Reading Workshop 4.)

Key Literary Elements

Recognizing and thinking about the following literary elements will help you

understand a text more fully.

■ Theme: the main idea, or message, of a story, poem, novel, or play.

Sometimes this idea is stated directly. More often it’s revealed gradually

through plot, character, setting, and other elements. (See “The Lion, the

Hare, and the Hyena.”)

■ Character: a person or animal in a story. (If a character is an animal, it

displays human qualities and behaviors.) Characterization is the methods

a writer uses to develop a character’s personality. (See “Jeremiah’s Song.”)

■ Cultural allusions: a reference to something that has special importance or meaning for a particular group of people. (See “We Are

All One.”)

■ Dialect: a variation of a language spoken by a particular group of people, usually within a certain region. In a dialect, words may have different

pronunciations, forms, and meanings than the same words have in the

standard language. (See “Voices—and Stories—from the Past.”)

Genre Focus: Folktale 653

UNIT 6 GENRE FOCUS

The notes in the side columns model

how to use the skills and elements

you read about on pages 652–653.

Folktale

ACTIVE READING MODEL

retold by Julius Lester

B

rer Rabbit was in the woods one afternoon when a

great wind came up. It blew on the ground and it blew in

the tops of the trees. It blew so hard that Brer Rabbit was

afraid a tree might fall on him, and he started running. 1

He was trucking through the woods when he ran

smack into Brer Lion. Now, don’t come telling me ain’t no

lions in the United States. Ain’t none here now. But back

in yonder times, all the animals lived everywhere. The

lions and tigers and elephants and foxes and what ’nall

run around with each other like they was family. So

that’s how come wasn’t unusual for Brer Rabbit to run up

on Brer Lion like he done that day. 2 3

“What’s your hurry, Brer Rabbit?”

“Run, Brer Lion! There’s a hurricane coming.”

Brer Lion got scared. “I’m too heavy to run, Brer Rabbit.

What am I going to do?”

“Lay down, Brer Lion. Lay down! Get close to the

ground!”

Brer Lion shook his head. “The wind might pick me up

and blow me away.”

“Hug a tree, Brer Lion! Hug a tree!”

“But what if the wind blows all day and into the night?”

“Let me tie you to the tree, Brer Lion. Let me tie you to

the tree.” 4

654 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

1 Key Reading Skill

Predicting I wonder what will

happen next. It says the wind is

blowing hard, so maybe a tree

really will fall on Brer Rabbit.

2 Key Reading Skill

Questioning I don’t understand

what “trucking” means here. Is

Brer Rabbit driving a truck? I’ll

read on to see if I can answer

my own question.

3 Key Literary Element

Dialect, Character, and Cultural

Context The storyteller speaks

in a dialect. We learned in

school that Brer Rabbit is in lots

of African American folktales. So

the dialect and culture must be

old-time African American.

4 Key Reading Skill

Understanding Cause and

Effect The strong winds are the

cause, and the effect is Brer

Lion’s fear.

UNIT 6 GENRE FOCUS

Emma’s Lion, 1994.

Christian Pierre, Acrylic

on Masonite, 16 x 20 in.,

Private collection.

Brer Lion liked that idea. Brer Rabbit tied him to the

tree and sat down next to it. After a while, Brer Lion got

tired of hugging the tree.

“Brer Rabbit? I don’t hear no hurricane.”

Brer Rabbit listened. “Neither do I.”

“Brer Rabbit? I don’t hear no wind.”

Brer Rabbit listened. “Neither do I.”

“Brer Rabbit? Ain’t a leaf moving in the trees.”

Brer Rabbit looked up. “Sho’ ain’t.”

“So untie me.”

“I’m afraid to, Brer Lion.” 5

Brer Lion began to roar. He roared so loud and so long,

the foundations of the Earth started shaking. Least that’s

what it seemed like, and the other animals came from all

over to see what was going on.

When they got close, Brer Rabbit jumped up and began

strutting around the tied-up Brer Lion. When the animals

saw what Brer Rabbit had done to Brer Lion, you’d better

believe it was the forty-eleventh of Octorerarry before

they messed with him again. 6 ❍

Folktale

ACTIVE READING MODEL

5 Key Reading Skill

Analyzing Brer Rabbit is

afraid he’ll be killed if he

unties Brer Lion!

6 Key Literary Element

Theme Brer Rabbit gets

everyone’s respect by outsmarting Brer Lion. So

maybe the main message

of this story is that being

smart is better than

being big and strong.

Write to Learn You can learn a great deal through the dialogue in a

story. Write a paragraph explaining what you learned about the main

characters from the dialogue in this folktale.

Study Central Visit www.glencoe.com and click on Study Central

to review folktales.

Genre Focus: Folktale 655

Christian Pierre/SuperStock

READING WORKSHOP 1

Skills Focus

You will practice using these skills when you

read the following selections:

• “The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena,” p. 660

• “Charles,” p. 668

Reading

• Understanding cause and

effect

Literature

• Identifying the theme of a

selection

Vocabulary

• Understanding and using

idioms and slang

Writing/Grammar

• Identifying direct and

indirect objects

Skill Lesson

Understanding

Cause and Effect

Learn It!

What Is It? Understanding the reason things happen is a big part of what human beings do. We want

to know “why.” Why is the sky blue? Why does water

run downhill? These are the simple beginnings of all

the complicated science we know today. We are

always looking for the cause of things.

• A cause is a person, event, or condition that makes

something happen.

• What happens as a result is an effect.

You will find cause and effect relationships in just

about everything you read. That’s because cause

and effect is everywhere in life. And writers also use

cause and effect to organize information for you,

especially in social studies and science reading.

rights reserved.

RSAL PRESS SYNDICATE. All

Reprinted with Permission of UNIVE

BALDO © 2000 Baldo Partnership.

Analyzing Cartoons

Objectives (pp. 656–657)

Reading Understand cause

and effect

656 UNIT 6

Universal Press Syndicate

Chewing gum while practicing soccer

(cause) can lead to trouble (effect). Words

and phrases like if/then, therefore, and as

a result signal cause and effect. Sometimes

“Now I know why” signals it, too.

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

Why Is It Important? As you read, you often ask, “Why?” You need to

be able to recognize when the author is giving you the answer. That applies

to big questions: Why is there suffering in the world? It also applies to

smaller questions: Why did the main character in this story tell a lie?

Remember that one cause may have many effects. When someone drops a

match in a forest, there are millions of effects. And one effect may have

many causes. The causes of winning a race include being healthy, trying

your best, and so forth.

Study Central Visit www.glencoe

.com and click on Study Central to

review understanding cause and

effect.

How Do I Do It? First, keep asking “Why?” Then, look for signal words

that help you know that your question is being answered, words like

because, so, so that, if . . . then, and as a result of. These signal words

are often there when you’re looking for a cause. When they’re not, your

“why” question will give you a start. Here’s how one student identified

cause and effect in ”The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena.”

Simba had hurt his leg so badly that he was unable

to provide food for himself. Sunguru the Hare

happened to be passing his cave one day. Looking

inside, Sunguru realized that the lion was starving.

How can a big lion like Simba starve? Guess there must

be a reason. Ok, it said he hurt his leg and couldn’t get

food. That means he can’t hunt. So the cause is his leg is

hurt so bad that he can’t hunt, therefore he’s starving.

That’s the effect of the hurt leg.

Practice It!

Look at the sentences below. See if you can identify the cause and the

effect in each one.

• Hal ate too many cookies, so he got sick.

• Water runs downhill because of gravity.

• The wind blew so hard that my hat went flying.

Use It!

As you read “The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena” and “Charles,”

take notes on the characters, what they do, and the situations each

of them are in. This will help you to identify the cause-and-effect

relationships.

Reading Workshop 1 Understanding Cause and Effect 657

Getty Images

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

Before You Read

Meet the Author

Phyllis Savory has written

and edited tales that have

strong African influences. By

recording ancient tales told

from generation to generation, she helps readers young

and old discover delightful

and enchanting worlds.

Author Search For more

about Phyllis Savory, go to

www.glenocoe.com.

The Lion, the Hare, and

the Hyena

Vocabulary Preview

solitude (SOL uh tood) n. the state of being alone (p. 660) The lion

enjoyed his solitude.

accumulate (uh KYOO myuh layt) v. to increase gradually in quantity or

number (p. 660) The hyena wanted the delicious bones that had begun

to accumulate.

conspicuous (kun SPIK yoo us) adj. quite noticeable (p. 662) The lion’s

absence was very conspicuous.

Definition Trade-Off With a partner or small group, take turns calling

out a vocabulary word and having the partner give the definition, or call

out the definition and have the partner give the word.

English Language Coach

Idioms An idiom (ID ee um) is a word or phrase that has a special meaning. Every language has idioms, and they can cause problems for someone

who hasn’t heard them before or for someone who didn’t grow up speaking the language. Often, the problem can be solved quickly because many

idioms make sense if you think about them.

Even if an idiom is unfamiliar, you can often figure out what it means. “I

can’t talk; I’m all tied up” would probably make sense to someone who’d

never heard the expression. So would “I think I bit off more than I can

chew.” These expressions are figurative. That is, they communicate an idea

that is not the the literal (actual and ordinary) meaning of the words. Still,

the ideas they communicate are clear.

Some idioms, though, you just have to know. If you’d never heard “shoot

the breeze,” how would you know what “They were shooting the breeze

on the front porch” meant? You wouldn’t. All you could do would be to try

to figure it out from the context, check shoot or breeze in the dictionary

(sometimes idioms are listed), or ask someone.

Objectives (pp. 658–663)

Reading Understand cause and effect

• Make connections from text to self

Literature Identify literary elements:

theme

Vocabulary Understand idioms

Group Talk With a small group, discuss what the following idioms mean.

If you don’t know them, try to figure out what they might mean.

1. Maybe you should leave well enough alone.

2. I don’t think she’s playing with a full deck.

3. Try to keep your chin up.

658 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

658-659U6BYR_845477.indd 658

3/9/07 3:54:19 PM

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

Skills Preview

Get Ready to Read

Key Reading Skill: Understanding

Cause and Effect

Connect to the Reading

In a story, cause and effect relationships are important

for many reasons. One of the most important is that

they move the story along. They are part of the plot.

This event happens, causing that event to happen,

which then causes another event to happen. The plot

is a kind of chain reaction, a series of causes and

events. As you read “The Lion, the Hare, and the

Hyena,” notice the people, events, and conditions that

cause other things to happen.

Key Literary Element: Theme

The theme of a story is the message that the writer

most wants to communicate. It is the main idea of

the story.

Origin stories, such as “The Lion, the Hare, and the

Hyena,” always include an explanation of something

in nature. That provides the basic plot of the story.

“Why is this the way it is?” “Because this happened.”

Such stories have a cause and effect structure.

But the structure is not the theme. Origin stories deal

with another kind of “truth” about nature and human

life. Doing the following while you read will help you

understand the theme:

• Look at the good and bad things the characters do.

• Watch for who wins and who loses and why.

• Does someone get punished? Why?

• Does someone learn a lesson? What is it?

Interactive Literary Elements Handbook

To review or learn more about the literary

elements, go to www.glencoe.com.

How would you feel if you were all alone and so sick

that you couldn’t do the things you needed to do?

Who would you trust to come into your home and

help you? Is there anyone you feel you could not

trust? Why?

Think-Pair-Share Discuss what friends do to help

each other in times of need. What would you do to

help a friend? How can you tell if a person is a true

friend?

Build Background

“The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena” is a folktale

from Kenya.

• In this folktale, you’ll read about animals that

possess human traits.

• One animal is greatly respected.

• One animal is looked down on and hated and

must resort to trickery to get what he wants.

Set Purposes for Reading

Read “The Lion, the Hare, and

the Hyena” to find out how origin stories work and

why people tell them.

Set Your Own Purpose What would you like to

learn from the selection to help you answer the Big

Question? Write your own purpose on the “Lion, the

Hare, and the Hyena” page of Foldable 6.

Keep Moving

Use these skills as you read the following

selection.

The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena 659

READING WORKSHOP 1

Retold by Phyllis Savory

A

lion named Simba once lived alone in a cave. In his

younger days the solitude had not worried him, but not very

long before this tale begins he had hurt his leg so badly that

he was unable to provide food for himself. Eventually he

began to realize that companionship had its advantages.

Things would have gone very badly for him, had not

Sunguru the Hare happened to be passing his cave one day.

Looking inside, Sunguru realized that the lion was starving.

He set about at once caring for his sick friend and seeing to

his comfort.

Under the hare’s careful nursing, Simba gradually regained

his strength until finally he was well enough to catch small

game for the two of them to eat. Soon quite a large pile of

bones began to accumulate outside the entrance to the lion’s

cave. 1

1

Key Reading Skill

Understanding Cause and

Effect How did the hare come

to live with the lion?

Vocabulary

solitude (SOL uh tood) n. the state of being alone

accumulate (uh KYOO myuh layt) v. to increase gradually in quantity or number

660 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

660-663U6SEL_845477.indd 660

3/9/07 3:54:40 PM

READING WORKSHOP 1

One day Nyangau the Hyena, while sniffing around in the

hope of scrounging something for his supper, caught the

appetizing smell of marrow-bones.1 His nose led him to

Simba’s cave, but as the bones could be seen clearly from

inside he could not steal them with safety. Being a cowardly

fellow, like the rest of his kind, he decided that the only way

to gain possession of the tasty morsels would be to make

friends with Simba. He therefore crept up to the entrance of

the cave and gave a cough.

“Who makes the evening hideous with his dreadful

croakings?” demanded the lion, rising to his feet and

preparing to investigate the noise.

“It is I, your friend, Nyangau,” faltered2 the hyena, losing

what little courage he possessed. “I have come to tell you how

sadly you have been missed by the animals, and how greatly

we are looking forward to your early return to good health!” 2

“Well, get out,” growled the lion, “for it seems to me that a

friend would have inquired about my health long before this,

instead of waiting until I could be of use to him once more.

Get out, I say!”

Practice the Skills

2

Key Literary Element

Theme Why is Nyangau pretending to be Simba’s friend?

Is he behaving the way a real

friend would? Could his actions

be a clue to the theme?

Moonlight Studios

1. To scrounge is to get by finding, begging, borrowing, or stealing. Marrow is the soft substance

found in the hollow centers of most bones.

2. When Nyangau faltered, he spoke brokenly or weakly because of fear.

The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena 661

READING WORKSHOP 1

The hyena shuffled off with alacrity, his scruffy tail tucked

between his bandy legs, followed by the insulting giggles of

the hare. But he could not forget the pile of tempting bones

outside the entrance to the lion’s cave.

“I shall try again,” resolved the thick-skinned hyena. A

few days later he made a point of paying his visit while the

hare was away fetching water to cook the evening meal. 3

He found the lion dozing at the entrance to his cave.

“Friend,” simpered Nyangau, “I am led to believe that the

wound on your leg is making poor progress, due to the

underhanded treatment that you are receiving from your socalled friend Sunguru.”

“What do you mean?” snarled the lion malevolently.3 “I

have to thank Sunguru that I did not starve to death during

the worst of my illness, while you and your companions were

conspicuous by your absence!”

“Nevertheless, what I have told you is true,” confided the

hyena. “It is well known throughout the countryside that

Sunguru is purposely giving you the wrong treatment for

your wound to prevent your recovery. For when you are well,

he will lose his position as your housekeeper—a very

comfortable living for him, to be sure! Let me warn you, good

friend, that Sunguru is not acting in your best interests!” 4

At that moment the hare returned from

the river with his gourd filled with water.

“Well,” he said, addressing the hyena as he

put down his load, “I did not expect to see

you here after your hasty and inglorious

Visual Vocabulary

A gourd is a harddeparture from our presence the other day.

rinded inedible fruit

Tell me, what do you want this time?”

that’s sometimes

Simba turned to the hare. “I have been

used as a utensil.

listening,” he said, “to Nyangau’s tales

about you. He tells me that you are renowned throughout the

countryside for your skill and cunning4 as a doctor. He also

tells me that the medicines you prescribe are without rival.

3. To say or act with hatred is to do so malevolently.

4. To be renowned is to be famous. Here, cunning means “skillful in the use of resources.”

Vocabulary

conspicuous (kun SPIK yoo us) adj. quite noticeable

662 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

Siede Preis/Getty Images

Practice the Skills

3

English Language Coach

Idiom From the context of the

sentence, can you figure out

what thick-skinned means?

Thick skin protects an animal

so harmful things don’t get

through. What didn’t “get

through” to the hyena?

4

Key Literary Element

Theme What was Sunguru willing to do to earn Simba’s friendship? How did Nyangau expect to

get it? Do these motives give you

a clue about the theme?

READING WORKSHOP 1

Moonlight Studios

But he insists that you could have cured the wound on my leg

a long time ago, had it been in your interest to do so. Is this

true?”

Sunguru thought for a moment. He knew that he had to

treat this situation with care, for he had a strong suspicion

that Nyangau was trying to trick him. 5

“Well,” he answered with hesitation, “yes, and no. You see,

I am only a very small animal, and sometimes the medicines

that I require are very big, and I am unable to procure5

them—as, for instance, in your case, good Simba.”

“What do you mean?” spluttered the lion, sitting up and at

once showing interest.

“Just this,” replied the hare. “I need a piece of skin from the

back of a full-grown hyena to place on your wound before it

will be completely healed.”

Hearing this, the lion sprang onto Nyangau before the

surprised creature had time to get away. Tearing a strip of

skin off the foolish fellow’s back from his head to his tail, he

clapped it on the wound on his leg. As the skin came away

from the hyena’s back, so the hairs that remained stretched

and stood on end. To this day Nyangau and his kind still

have long, coarse hairs standing up on the crests of their

misshapen bodies. 6

Sunguru’s fame as a doctor spread far and wide after this

episode, for the wound on Simba’s leg healed without further

trouble. But it was many weeks before the hyena had the

courage to show himself in public again. 7 ❍

Practice the Skills

5

Key Literary Element

Theme Using what you know

about the characters and the plot

of this story, what would you say

the implied theme is?

6

Key Reading Skill

Understanding Cause and

Effect What thing in nature has

this origin story tried to explain?

According to the story, what

was the cause and what was the

effect?

7

Why do you think cultures all

around the world have created

origin stories? Write your answer

on the “Lion, the Hare, and the

Hyena” page of Foldable 6. Your

response will help you complete

the Unit Challenge later.

5. Procure means “to get or gain possession of.”

The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena 663

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

After You Read

The Lion, the Hare, and

the Hyena

Answering the

1. Now that you’ve read this folktale, what are some stories that you’ve

heard in your own family that you would like to continue to tell?

2. Recall Why was Simba starving at the beginning of the story?

T IP Right There

Critical Thinking

3. Interpret “The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena” teaches a lesson. What

do you think that lesson is?

T IP Author and Me

Moonlight Studios

4. Infer What would have happened to Simba the Lion had Sunguru the

Hare not come along?

T IP Author and Me

5. Interpret Were Nyangau’s claims that he was Simba’s friend honest?

Explain.

T IP Think and Search

6. Interpret What saved the situation for Sunguru?

T IP Author and Me

Write About Your Reading

Use the RAFT system to write about “The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena.”

Role: Simba the Lion

Objectives (pp. 664–665)

Reading Understand cause and effect

Literature Identify literary elements:

theme

Vocabulary Understand idioms

Writing Use the RAFT system: letter to the

editor

Grammar Identify direct objects

Audience: Newspaper readers

Format: Letter to the editor

Topic: Animals in the forest have been saying that Simba was wrong to

tear a strip off Nyangau. Write a letter from Simba defending what he did.

664 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

Skills Review

Key Reading Skill: Understanding

Cause and Effect

In each of the following sentences from the story, the

underlined words state an effect. Explain what you

think the cause is.

7. “In his younger days the solitude had not worried

him, but not very long before this tale begins he

had hurt his leg so badly that he was unable to

provide food for himself.”

8. “His nose led him to Simba’s cave, but as the

bones could be seen clearly from inside he could

not steal them with safety.”

9. “Sunguru’s fame as a doctor spread far and wide

after this episode, for the wound on Simba’s leg

healed without further trouble.”

Key Literary Element: Theme

17. But I was on pins and needles all day. I was very

nervous about my test grade.

18. When I got my test paper back, I was on cloud

nine! I was so happy I passed.

Grammar Link: Identifying

Direct Objects

Some verbs just aren’t complete without an object.

You know that a sentence requires a subject and a

verb, but look at this sentence:

• Kayla threw.

To complete the thought (and the sentence), you

need to say what Kayla threw.

• Kayla threw the ball.

In that sentence, ball is the direct object of the verb.

It answers the question “What or whom?”

10. Who was successful in this story, the good friend

or the bad friend? What does this tell you about

the theme of the story?

There can be more than one direct object in a

sentence.

• Kayla threw the ball and the glove.

Vocabulary Check

A direct object can have modifiers, just as a subject or

verb can.

• I baked a big cake with pink frosting.

Write the vocabulary word that best matches each

synonym below. Two words will be used twice.

11. increase

14. aloneness

12. visible

15. noticeable

13. gather

English Language Coach Use the context clues in

each sentence to help you figure out the meaning of

the idioms.

16. English is very easy for my friend Aricelli. She

thought the test was a piece of cake.

Grammar Practice

Identify the direct objects in the following sentences.

Write your answers on a separate sheet of paper.

19. Dad served cabbage for dinner.

20. The falling tree smashed my bicycle.

21. Marc knows the names of all the presidents.

22. Peter told the story very well.

Writing Application Look back at the Write About

Your Reading assignment to see if you used any direct

objects.

Web Activities For eFlashcards, Selection

Quick Checks, and other Web activities, go to

www.glencoe.com.

The Lion, the Hare, and the Hyena 665

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

Before You Read

Charles

Vocabulary Preview

S h ir

le y Ja ck so n

Meet the Author

Shirley Jackson’s fiction is

filled with strange twists and

turns. In most of her novels

and short stories, she

explores the darker side of

human life. However,

Jackson also wrote humorously about family life, as

she does in “Charles.”

Jackson was born in 1919

and died in 1965. See page

R4 of the Author Files for

more on Shirley Jackson.

Author Search For more

about Shirley Jackson, go to

www.glencoe.com.

raucous (RAW kus) adj. loud and rough sounding (p. 668) Laurie’s voice

was sounding more and more raucous every day.

insolently (IN suh lunt lee) adv. in a boldly rude manner (p. 668) He

began to speak insolently to his parents.

simultaneously (sy mul TAY nee us lee) adv. at the same time (p. 670)

Laurie’s parents simultaneously decided they had to do something.

reformation (reh fur MAY shun) n. a change for the better; improvement

(p. 671) It was clear that Laurie’s behavior needed reformation.

cynically (SIN uh kul ee) adv. in a way that shows doubt or disbelief;

doubtfully (p. 671) His father cynically shook his head.

Vocabulary Concentration With a partner, copy the words onto one set

of index cards and the definitions onto another set. Mix the cards up and

place them face down on a desk or table. Take turns turning the cards over

two at a time. When you match a word and its definition, you may take the

pair. Write sentences with the words you have matched.

English Language Coach

Slang Slang is informal language that is appropriate for casual conversation but not for formal speech or writing. Some slang is widely understood.

Some, however, may be used and understood only by people within a certain social group.

Slang may use made-up words, such as mondo or mongo, meaning

“extremely.” Some, such as dis to mean disrespect, involves abbreviations.

Most slang, though, consists of common English words used with different

meanings.

Slang

down with

bail

Slang Meaning

in agreement with a plan

to leave or abandon

tight

emotionally close

Objectives (pp. 666–673)

Reading Understand cause and effect

• Make connections from text to self

Literature Identify literary elements:

theme

Vocabulary Understand slang

666 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

Lawrence J. Hyman/courtesy Bantam Books

Example

Sure, I’m down with that.

I’m counting on you, so

don’t bail.

She’ll help me; we’re tight.

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

Skills Preview

Get Ready to Read

Key Reading Skill: Understanding

Cause and Effect

Connect to the Reading

Why do you hang out with certain people? You can

answer that a lot of different ways. Because they’re

my friends. Because I like them. Because we have a

good time together. Those are your reasons. When it

comes to characters in a story and their motives for

doing certain things, you can look at these reasons as

causes.

As you read “Charles,” use the following tips to help

you recognize cause and effect in both the plot and

the characters’ motivations:

• Look for each character’s reasons for doing what he

or she does.

• Look for signal words, such as why, because,

if . . . then, so that, and therefore.

• See what events cause the teacher to do certain

things in class.

Key Literary Element: Theme

Because the theme of a story is not always direct, you

must dig a little deeper to understand the main idea.

Laurie, his parents, and Charles are the main characters in “Charles.” As you read the selection, think

about each character.

• What are the characters doing?

• How are they feeling about the situation they are in?

• What happens at the end?

• How do the characters react to the ending? Who is

affected by the ending?

• What conclusions do you come to about the ending?

Keep these questions in mind as you try to determine

the theme.

Interactive Literary Elements Handbook

To review or learn more about the literary

elements, go to www.glencoe.com.

You have probably often heard just one person’s side

of a story and found out later that there was more to

the story than you knew. Think about a time when

that happened. Did hearing more of the story change

your mind about what happened?

Write to Learn In your Learner’s Notebook, freewrite about a time a friend or family member told you

only one side of a story.

Build Background

Children entering school must learn to get along with

each other, follow directions, and help with classroom

activities. In preschool and kindergarten, children

become accustomed to a school setting and learn to

play together. At least, that’s the plan. In “Charles,”

things don’t exactly follow the plan.

• Laurie, a kindergarten boy, takes delight in telling

his parents about school each day.

• His parents are shocked to hear Laurie’s descriptions of the horrible classroom behavior of a boy

named Charles.

• Seeing Charles as a bad influence on her son,

Laurie’s mother decides to speak to the other boy’s

parents.

Set Purposes for Reading

Read to find out why Laurie is

sharing stories about Charles.

Set Your Own Purpose What would you like to

learn from the selection to help you answer the Big

Question? Write your own purpose on the “Charles”

page of Foldable 6.

Keep Moving

Use these skills as you read the following

selection.

Charles 667

READING WORKSHOP 1

by Shirley Jackson

T

he day my son Laurie started kindergarten he renounced1

corduroy overalls with bibs and began wearing blue jeans

with a belt; I watched him go off the first morning with the

older girl next door, seeing clearly that an era of my life was

ended, my sweet-voiced nursery-school tot replaced by a longtrousered, swaggering2 character who forgot to stop at the

corner and wave good-bye to me. 1

He came home the same way, the front door slamming

open, his cap on the floor, and the voice suddenly become

raucous shouting, “Isn’t anybody here?”

At lunch he spoke insolently to his father, spilled his baby

sister’s milk, and remarked that his teacher said we were not

to take the name of the Lord in vain.

“How was school today?” I asked, elaborately casual.

“All right,” he said.

“Did you learn anything?” his father asked.

1. When Laurie renounced overalls, he rejected or gave them up.

2. Swaggering means carrying oneself in a proud manner.

Vocabulary

raucous (RAW kus) adj. loud and rough sounding

insolently (IN suh lunt lee) adv. in a boldly rude manner

668 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

Matt Meadows

Practice the Skills

1

Reviewing Skills

Connecting Do you remember

your first day at kindergarten?

How do you think your parents

felt that day?

READING WORKSHOP 1

Laurie regarded his father coldly. “I didn’t learn nothing,”

he said.

“Anything,” I said. “Didn’t learn anything.”

“The teacher spanked a boy, though,” Laurie said,

addressing his bread and butter. “For being fresh,” he added,

with his mouth full.

“What did he do?” I asked. “Who was it?”

Laurie thought. “It was Charles,” he said. “He was fresh.

The teacher spanked him and made him stand in a corner.

He was awfully fresh.” 2

“What did he do?” I asked again, but Laurie slid off his

chair, took a cookie, and left, while his father was still saying,

“See here, young man.”

The next day Laurie remarked at lunch, as soon as he sat

down, “Well, Charles was bad again today.” He grinned

enormously and said, “Today Charles hit the teacher.”

“Good heavens,” I said, mindful of the Lord’s name, “I

suppose he got spanked again?”

“He sure did,” Laurie said. “Look up,” he said to his father.

“What?” his father said, looking up.

“Look down,” Laurie said. “Look at my thumb. Gee, you’re

dumb.” He began to laugh insanely.

“Why did Charles hit the teacher?” I asked quickly.

“Because she tried to make him color with red crayons,”

Laurie said. “Charles wanted to color with green crayons so

he hit the teacher and she spanked him and said nobody play

with Charles but everybody did.” 3

The third day—it was Wednesday of the first week—

Charles bounced a see-saw on to the head of a little girl and

made her bleed, and the teacher made him stay inside all

during recess. Thursday Charles had to stand in a corner

during story-time because he kept pounding his feet on the

floor. Friday Charles was deprived of blackboard privileges

because he threw chalk.

On Saturday I remarked to my husband, “Do you think

kindergarten is too unsettling for Laurie? All this toughness,

and bad grammar, and this Charles boy sounds like such a

bad influence.”

“It’ll be all right,” my husband said reassuringly. “Bound to

be people like Charles in the world. Might as well meet them

now as later.”

Practice the Skills

2

Key Reading Skill

Understanding Cause and

Effect What made the teacher

spank Charles and put him in

a corner?

3

Key Reading Skill

Understanding Cause and

Effect The teacher told the class

not to play with Charles—but

they did. What effect do you

think this had on Charles?

Charles 669

READING WORKSHOP 1

On Monday Laurie came home late, full of news.

“Charles,” he shouted as he came up the hill; I was

waiting anxiously on the front steps. “Charles,” Laurie

yelled all the way up the hill, “Charles was bad again.”

“Come right in,” I said, as soon as he came close

enough. “Lunch is waiting.”

“You know what Charles did?” he demanded,

following me through the door. “Charles yelled so in

school they sent a boy in from first grade to tell the

teacher she had to make Charles keep quiet, and so

Charles had to stay after school. And so all the

children stayed to watch him.”

“What did he do?” I asked.

“He just sat there,” Laurie said, climbing into his

chair at the table. “Hi, Pop, y’old dust mop.” 4

“Charles had to stay after school today,” I told my husband.

“Everyone stayed with him.”

“What does this Charles look like?” my husband asked

Laurie. “What’s his other name?”

“He’s bigger than me,” Laurie said. “And he doesn’t have

any galoshes and he doesn’t ever wear a jacket.”

Monday night was the first Parent-Teachers meeting, and

only the fact that the baby had a cold kept me from going; I

wanted passionately to meet Charles’s mother. On Tuesday

Laurie remarked suddenly, “Our teacher had a friend come to

see her in school today.”

“Charles’s mother?” my husband and I asked simultaneously.

“Naaah,” Laurie said scornfully. “It was a man who came

and made us do exercises, we had to touch our toes. Look.”

He climbed down from his chair and squatted down and

touched his toes. “Like this,” he said. He got solemnly back

into his chair and said, picking up his fork, “Charles didn’t

even do exercises.”

“That’s fine,” I said heartily. “Didn’t Charles want to do

exercises?”

“Naaah,” Laurie said. “Charles was so fresh to the teacher’s

friend he wasn’t let do exercises.”

Vocabulary

simultaneously (sy mul TAY nee us lee) adv. at the same time

670 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

Simon Watson/Getty Images

Practice the Skills

4

Reviewing Skills

Connecting This is the second

time Laurie has spoken rudely to

his father. Would you talk to your

parents like this? What effect

would it bring if you did?

READING WORKSHOP 1

“Fresh again?” I said.

“He kicked the teacher’s friend,” Laurie said. “The teacher’s

friend told Charles to touch his toes like I just did and

Charles kicked him.”

“What are they going to do about Charles, do you

suppose?” Laurie’s father asked him.

Laurie shrugged elaborately. “Throw him out of school, I

guess,” he said.

Wednesday and Thursday were routine; Charles yelled

during story hour and hit a boy in the stomach and made

him cry. On Friday Charles stayed after school again and so

did all the other children.

With the third week of kindergarten Charles was an

institution3 in our family; the baby was being a Charles when

she cried all afternoon; Laurie did a Charles when he filled

his wagon full of mud and pulled it through the kitchen; even

my husband, when he caught his elbow in the telephone cord

and pulled telephone, ashtray, and a bowl of flowers off the

table, said, after the first minute, “Looks like Charles.” 5

During the third and fourth weeks it looked like a

reformation in Charles; Laurie reported grimly at lunch on

Thursday of the third week, “Charles was so good today the

teacher gave him an apple.” 6

“What?” I said, and my husband added warily, “You mean

Charles?”

“Charles,” Laurie said. “He gave the crayons around and he

picked up the books afterward and the teacher said he was

her helper.”

“What happened?” I asked incredulously.

“He was her helper, that’s all,” Laurie said, and shrugged.

“Can this be true, about Charles?” I asked my husband that

night. “Can something like this happen?”

“Wait and see,” my husband said cynically. “When you’ve

got a Charles to deal with, this may mean he’s only plotting.4”

Practice the Skills

5

English Language Coach

Slang What does the name

Charles mean when Laurie’s

family uses it in the phrases

“being a Charles,” “did a

Charles,” and “looks like a

Charles”?

6

Key Reading Skill

Understanding Cause and

Effect How is Charles’s good

behavior being rewarded?

3. Here, institution means a “regular feature or tradition.”

4. Plotting means planning with evil intent.

Vocabulary

reformation (reh fur MAY shun) n. a change for the better; improvement

cynically (SIN uh kul ee) adv. in a way that shows doubt or disbelief; doubtfully

Charles 671

READING WORKSHOP 1

He seemed to be wrong. For over a week Charles was the

teacher’s helper; each day he handed things out and he

picked things up; no one had to stay after school.

“The P.T.A. meeting’s next week again,” I told my husband

one evening. “I’m going to find Charles’s mother there.”

“Ask her what happened to Charles,” my husband said. “I’d

like to know.”

“I’d like to know myself,” I said.

On Friday of that week things were back to normal. “You

know what Charles did today?” Laurie demanded at the

lunch table, in a voice slightly awed. “He told a little girl to

say a word and she said it and the teacher washed her mouth

out with soap and Charles laughed.”

“What word?” his father asked unwisely, and Laurie said,

“I’ll have to whisper it to you, it’s so bad.” He got down off

his chair and went around to his father. His father bent his

head down and Laurie whispered joyfully. His father’s eyes

widened. 7

“Did Charles tell the little girl to say that?” he asked

respectfully.

“She said it twice,” Laurie

said. “Charles told her to say it

twice.”

“What happened to

Charles?” my husband asked.

“Nothing,” Laurie said. “He

was passing out the crayons.”

Monday morning Charles

abandoned the little girl and

said the evil word himself

three or four times, getting his

mouth washed out with soap

each time. He also threw chalk.

My husband came to the

door with me that evening as I

set out for the P.T.A. meeting.

“Invite her over for a cup of tea

after the meeting,” he said. “I

want to get a look at her.”

“If only she’s there,” I said

prayerfully.

672 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

Bridgeman Art Library

Practice the Skills

7

Reviewing Skills

Comparing and Contrasting

Compare Laurie’s behavior here

to Charles’s behavior, as Laurie

describes it.

Playground, Crook, P.J. (b. 1945).

Acrylic on canvas, 116.8 X 132 cm.

Private collection.

READING WORKSHOP 1

“She’ll be there,” my husband said.

“I don’t see how they could hold a P.T.A. meeting without

Charles’s mother.”

At the meeting I sat restlessly, scanning each comfortable

matronly5 face, trying to determine which one hid the secret

of Charles. None of them looked to me haggard6 enough. No

one stood up in the meeting and apologized for the way her

son had been acting. No one mentioned Charles.

After the meeting I identified and sought out Laurie’s

kindergarten teacher. She had a plate with a cup of tea and a

piece of chocolate cake; I had a plate with a cup of tea and a

piece of marshmallow cake. We maneuvered up to one

another cautiously, and smiled.

“I’ve been so anxious to meet you,” I said. “I’m Laurie’s

mother.”

“We’re all so interested in Laurie,” she said.

“Well, he certainly likes kindergarten,” I said. “He talks

about it all the time.”

“We had a little trouble adjusting, the first week or so,” she

said primly, “but now he’s a fine little helper. With occasional

lapses,7 of course.”

“Laurie usually adjusts very quickly,” I said. “I suppose this

time it’s Charles’s influence.”

“Charles?”

“Yes,” I said, laughing, “you must have your hands full in

that kindergarten, with Charles.”

“Charles?” she said. “We don’t have any Charles in the

kindergarten.” 8 9 ❍

Practice the Skills

8

Key Literary Element

Theme What does this story

suggest about human nature?

9

Why do you think Laurie told

stories about a boy who didn’t

exist? Write your answer on the

“Charles” page of Foldable 6.

Your response will help you complete the Unit Challenge later.

5. Another word for matronly would be “motherly.” It refers to a mature woman, especially one

who is married and has children.

6. A haggard person looks worn out as a result of grief, worry, illness—or dealing with a boy like

Charles.

7. A lapse is a slipping or falling to a lower or worse condition.

Charles 673

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

After You Read

Charles

Answering the

1. Why do you think Laurie tells stories about Charles?

2. Recall How does Laurie report Charles’s good behavior and Charles’s

bad behavior?

T IP Think and Search

Critical Thinking

3. Interpret Why is Charles such a fascination in Laurie’s home?

T IP Author and Me

4. Infer Who is Charles?

T IP Author and Me

5. Synthesize What clues throughout the selection give you that

information?

T IP Think and Search

6. Evaluate Why do you think Laurie makes up all those stories?

T IP Author and Me

Write About Your Reading

Objectives (pp. 674–675)

Reading Understand cause and effect

Literature Identify literary elements:

theme

Vocabulary Understand slang

Writing Respond to literature: skit

Grammar Identify indirect objects

Write a skit about “Charles.” To get started, follow these steps:

Step 1: Think about which characters to include. Your choices will

depend on what you decide in Steps 2, 3, and 4.

Step 2: Decide whether the action will take place at Laurie’s home or

school.

Step 3: Decide on at least one cause and effect to show.

Step 4: Decide what will happen at the end.

Step 5: Write the skit.

Get some friends together to perform your skits for your class. (But behave.

Don’t do a Charles!)

674 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

Matt Meadows

READING WORKSHOP 1 • Understanding Cause and Effect

Skills Review

Key Reading Skill: Understanding Cause

and Effect

7. Why do you think Laurie turns into a “swaggering

character” when he starts kindergarten? Explain

your answer. (Hint: Think about the fact that

Laurie suddenly finds himself in a new place with

new people and new rules.)

8. Identify two good or positive things that Charles

does and how he is rewarded.

Key Literary Element: Theme

9. What do you think is the theme of “Charles”?

Explain your answer using examples from the

story.

Reviewing Skills: Comparing and

Contrasting

10. Comparing and Contrasting Compare

Laurie’s behavior at home with Charles’s actions

at school. How are their behaviors similar? How

are they different?

Vocabulary Check

Choose one of the vocabulary words to fill in each of

the blanks in the sentences below.

raucous

cynically

insolently

simultaneously

reformation

.

11. “Hey, old man, get a horse!” Geri yelled

12. The sounds from the ape’s cage were so

it

sounded like a huge party!

13. The city council is dishonest and needs

.

14. “I’m sorry, John. I don’t believe you can do it,” he

said

.

15. “You’re it!” Mary and Lisa shouted

.

16. English Language Coach If a slang meaning

for a word is used by enough people for a long

enough period, it becomes a regular meaning.

For example, fresh meaning “disrespectful,” was

slang in the mid-1800s but is now found in dictionaries. The meaning “extremely nice or superior” is still slang.

Write down two slang words or phrases and their

meanings. Use each one in a sentence that illustrates its meaning.

Grammar: Identifying

Indirect Objects

Direct objects answer the question “what or whom?”

• Joel wrote a letter.

If a sentence contains a direct object, it may also contain an indirect object. An indirect object answers the

question “to what or whom?” or “for what or whom?”

It usually comes before the direct object.

• Joel wrote Leanne a letter.

• Maya left Missy a beautiful present.

It’s important to know that a word is only an indirect

object if the word to or for is not stated. If it is, then

you have a prepositional phrase. There are no indirect

objects in the following sentences.

• Joel wrote a letter to Leanne.

• Maya left a beautiful present for Missy.

Grammar Practice

Identify the indirect object in each sentence.

17. The rider gave the horse an apple.

18. Habib handed them flowers.

19. James made me dinner last night.

20. My cousin gave her dog a bath.

Web Activities For eFlashcards, Selection

Quick Checks, and other Web activities, go to

www.glencoe.com.

Charles 675

WRITING WORKSHOP PART 1

Modern Folktale

Prewriting and Drafting

ASSIGNMENT Rewrite a

folktale in the present

Purpose: To tell a story

using all of the elements

of a folktale

Audience: You, your

teacher, and your classmates

Writing Rubric

As you work through this

writing assignment, you

should

• develop characters

• write dialogue

• develop a theme

• use third-person point of

view

• use correct spelling, grammar, usage, and mechanics

Objectives (pp. 676–679)

Writing Use the writing process:

draft • Write a folktale • Use literary elements: point of view,

dialogue, characterization, theme

Grammar Use compound and

complex sentences

Folktales are organized like other stories, usually in time order. They also

have characters, a setting, a plot (created through conflict), and a theme, just

like other stories. But folktales have some special characteristics, too.

• Characters in folktales are often larger-than-life humans or animals that act

like humans.

• The setting is usually long ago and sometimes in a faraway or makebelieve place.

• Some folktales (specifically fairy tales) include magic. Other folktales have

unusual elements such as talking animals.

In this Writing Workshop, you’ll rewrite a folktale in the present (as if it were

taking place today).

Prewriting

Get Ready to Write

Before you start writing, you’ll have to decide what folktale you want to

rewrite and plan the changes you’ll make.

Choose a Story

You can choose one of the folktales in this unit or another folktale you know.

• Make a list of the folktales you already know. Remember, folktales include

many different kinds of stories—animal stories, origin stories, legends,

trickster tales, fairy tales, tall tales, and myths.

• Look over the folktales in this unit. If one interests you, go ahead and read

it. (You don’t have to wait for your teacher to tell you to read it!)

• Choose a story that you think would be fun to rewrite. You may want to

choose your favorite story, or you may want to choose a story you don’t

like and make it into a story you do like.

Think About the Story

Think carefully about the story elements of the folktale you’re going to

rewrite. If you’re rewriting a folktale that you don’t know very well, you may

want to read the story a few times.

Fill in a chart like the one on the next page to familiarize yourself with the

key parts of the story. Make your chart in your Learner’s Notebook.

676 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

WRITING WORKSHOP PART 1

Folktale

Brer Rabbit and Brer Lion

Setting

The woods, somewhere in the United States, a long

time ago

Characters

Brer Rabbit, Brer Lion, the other animals

Major Events

Brer Lion lets Brer Rabbit tie him to a tree so he

doesn’t get blown away by the hurricane. The storm

never comes, but Brer Rabbit refuses to untie the lion.

When Brer Lion roars, all of the other animals come

and see that little Brer Rabbit has tied up the powerful

lion.

Writing Models For models and

other writing activities, go to

www.glencoe.com.

Magical or

Talking animals

Unusual Element

Theme

If you are smart enough, you can beat others who are

more powerful.

Make a Plan

Since your story is a retelling, you’ll need to keep some of the details from

the original folktale. You may want to use the same characters, events,

theme, or even setting. But don’t keep everything the same! Add your own

flavor to the folktale.

Figure out the main changes you want to make to the folktale before you

start drafting your story.

1. Take another look at your notes about the original folktale. Ask yourself

questions like the ones below.

• Where else could these events take place?

• What would these characters be like in current times?

• What other events could teach the same theme or lesson?

2. Use a story map to pull the elements of your folktale together. You might

also want to make notes about any magic in your story.

Characters

Setting

Jack Rabbit—lost in a dream world

a city street in England

Dan D. Lion—nervous, easily scared

Plot

Jack bumps into Dan on the street while thinking about a breeze he felt.

Dan freaks out thinking that the breeze might have been a cyclone.

Jack ties Dan to a taxicab.

The taxi drives away, and Jack wanders on in his dream world.

Theme

Living in a dream world can cause problems in the real world.

Writing Tip

Characters Make some

notes about how each character might talk. Does he or she

use big words, speak with an

accent, drag out every word,

or speak only in questions?

It’s up to you. Characters’

dialogue is based on the

personality of the character

and your imagination.

Writing Workshop Part 1

Modern Folktale 677

WRITING WORKSHOP PART 1

Drafting

Start Writing!

Grab your favorite pen, pencil, or keyboard and some blank paper. It’s time

to start writing!

Tell the Tale

Imagine you are a storyteller relating the folktale to a live audience. Use

your story map to guide you. Be sure your story has these elements of effective folktales.

• Tellers of folktales are usually outside the story. Use the third-person point

of view to tell what happens. (Remember to refer to characters by name or

as he and she.)

Writing Tip

Ideas You may want to write

a few ideas for openers for

your folktale and see which

one would be most interesting

to your readers.

• Folktales usually get to the point quickly. The start of “Brer Rabbit and Brer

Lion” sets up the story: “Brer Rabbit was in the woods one afternoon

when a great wind came up.” You can also start right in with action, dialogue, or an interesting statement.

Dan D. Lion was never the same after he bumped into

Jack Rabbit.

• Develop your characters by providing details about them. What are they

thinking? How do they act? Your readers need to know.

But, in his imagination, it had been a very nice tea

party.

Writing Tip

Writer’s Craft Make your

folktale more interesting by

using words besides said to

set up the dialogue. Try using

more specific and descriptive

words such as whined, shouted,

giggled, and whispered.

• Dialogue reveals characters’ personality and can give clues about the setting. A character that asks “What shall I do? Where can I hide?” is fearful

and anxious. “Would hiding inside that telephone booth make you

jumpy?” suggests a street setting.

• Your folktale should have a theme, or main idea. In “Brer Rabbit and Brer

Lion,” the theme appears through the characters and events of the story.

Brer Rabbit struts around the tied-up Brer Lion to show off what he’s done.

If you prefer, you can reveal the theme directly.

The moral of the story is “Never get mixed up with

someone who lives in a dream world.”

678 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

WRITING WORKSHOP PART 1

Grammar Link

Compound and

Complex Sentences

Sentences are made up of independent clauses

(which can stand alone as sentences) and dependent clauses (which cannot stand alone).

Independent clause: The lion was big.

Independent clause: The rabbit was smart.

Dependent clause: though the lion was big

What Are Compound and

Complex Sentences?

A compound sentence is made up of two or

more independent clauses joined together.

The lion was big, but the rabbit was smart.

independent

independent

A complex sentence is made up of one independent clause and one or more dependent clauses

joined together.

Though the lion was big, the rabbit was smart.

dependent

independent

Simple, complex, and compound: Writing only

in simple sentences limits you. When every sentence has the same pattern, every sentence

sounds the same. The sentences get boring, and

the writing sounds choppy.

How Do I Use Compound and

Complex Sentences?

Use compound sentences to show that two ideas

that are equally important go together.

• The wind howled.

• The thunder roared.

• The wind howled, and the thunder roared.

Use complex sentences to show that two ideas

that are not equally important go together. Put the

main idea in the independent, or main, clause. Put

the less important idea in the dependent clause.

Main idea: The rabbit survived.

Less important idea: He was smart

• Because he was smart, the rabbit survived.

Write to Learn Read your draft aloud. Does it

sound choppy? Combine simple sentences to form

compound and complex sentences.

Why Are Compound and

Complex Sentences Important?

You need to use all the sentence types to write

well. Compare the two paragraphs below.

Simple sentences only: Writing only in simple

sentences limits you. Every sentence has the same

pattern. Every sentence sounds the same. The

sentences get boring. The writing sounds choppy.

Looking Ahead

In Writing Workshop Part 2, you’ll revise and edit your folktale.

Writing Workshop Part 1

Modern Folktale 679

READING WORKSHOP 2

Skills Focus

You will practice using these skills when you

read the following selections:

• “The Boy and His Grandfather,” p. 684

• “Jeremiah’s Song,” p. 690

Reading

Skill Lesson

Questioning

Learn It!

• Questioning

Literature

• Understanding what a

character is like

• Recognizing direct and

indirect characterization

Vocabulary

• Recognizing and understanding idioms

• Understanding “phrase

words”

What Is It? Questioning is asking questions about

what you are reading. Have a conversation with

yourself as you read by asking and trying to answer

questions about the text. Feel free to ask anything!

Ask about what you don’t understand. Ask about the

importance of what you’re reading. You might ask

yourself questions like these:

• Who are the people in the story?

• Why did a person act a certain way?

• What just happened and how does it relate to what

happened before?

Answer the questions in your head or on paper.

Writing/Grammar

• Combining sentences

ate, Inc.

Permission of King Features Syndic

©Zits Partnership, Reprinted with

Analyzing Cartoons

Objectives

(pp. 680–681)

Reading Ask questions

680 UNIT 6

King Features Syndicate

The girl’s question here isn’t a bad one;

it just shows she has more to learn.

Asking questions helps us get specific

information fast—and helps us figure

things out.

READING WORKSHOP 2 • Questioning

Why Is It Important? As you answer your own questions, you’re making sure you understand what is going on. There may be times when you’ll

need to re-read to get more information.

How Do I Do It? As you read, stop after every paragraph or two. Ask

yourself questions to make sure you understand what you’ve read so far.

Here’s how one student checked to make sure he understood what he was

reading. Read this passage from “Lafff” by Lensey Namioka.

He sat down on the stool and twisted a dial.

I heard some bleeps, cheeps, and gurgles. Peter

disappeared. He must have done it with mirrors.

I looked around the garage. I peeked under the

tool bench. There was no sign of him.

Study Central Visit www.glencoe

.com and click on Study Central to

review questioning.

I just read about Peter disappearing. I can ask myself

questions to check if I understood the paragraph.

What happened to Peter? He seemed to have actually

disappeared.

Why do I wonder if he really disappeared? I’ve never

seen a person disappear and don’t believe that it is possible. But the writer says Peter disappeared and that

there was no sign of him anywhere in the garage.

What do I know about Peter? Peter is very smart, gets

good grades, and spends all of his time reading books. He

called himself Dr. Lu Manchu, the mad scientist. Maybe,

in this story, he built a time machine.

Practice It!

Read the first two paragraphs of “The Boy and His Grandfather.” In your

Learner’s Notebook, write two questions about what you want to know.

You might start your questions with the words what or why.

Use It!

As you read “The Boy and His Grandfather” and “Jeremiah’s Song,”

remember to stop and ask yourself questions.

Reading Workshop 2 Questioning 681

John Evans

READING WORKSHOP 2 • Questioning

Before You Read

The Boy and His

Grandfather

Vocabulary Preview

neglected (nih GLEK tud) v. ignored; not cared for; form of the verb

neglect (p. 684) The grandfather was neglected by his family.

frequently (FREE kwunt lee) adv. often (p. 685) The father wanted to see

grandfather frequently.

R ud

o lf o A . A n a y a

Meet the Author

Rudolfo A. Anaya was one of

the founding fathers of modern Hispanic American literature. He has written fiction,

plays, and essays, mostly set

in his native New Mexico.

Anaya often weaves Hispanic

legends and folktales into his

work. See page R1 of the

Author Files for more on

Rudolfo A. Anaya.

Ask About It! For each vocabulary word, ask a partner a question that

uses the word correctly. Have your partner give you an answer that also

uses the word correctly.

English Language Coach

Words in Phrases You know about multiple-meaning words. But there

are some words that have too many meanings to learn. It’s easier to learn

the way these words are used in combination with other words.

In “The Boy and His Grandfather,” the narrator says that the grandfather

“went hungry.” That simply means that he was hungry for longer than just

a short while. The word went is a form of the verb go, and it’s one of several English words that are often used in phrases like this. Here are some

others:

get take make do have give set put

Author Search For more

about Rudolfo A. Anaya, go to

www.glencoe.com.

When you see these words, you should ignore the main meaning of the

verb. The grandfather, for example, did not “go” anywhere. The important

word in the phrase is the adjective: hungry.

Group Work Look at the phrases below. Then, as a group, talk about

other phrases in which you use these verbs.

• do dishes

• make progress

• get ready

• go crazy

Objectives (pp. 682-685)

Reading Ask questions • Make connections from text to self

Literature Identify literary elements:

characterization

Vocabulary Understand words in

phrases

682 UNIT 6 Why Do We Share Our Stories?

Miriam Berkley

READING WORKSHOP 2 • Questioning

Skills Preview

Get Ready to Read

Key Reading Skill: Questioning

Connect to the Reading

When you ask questions as you read, you are making

sure that you understand the selection. You are also

asking about what is important.

Have you ever heard of the Golden Rule? It says,

“Treat others the way you want be treated.” In other

words, don’t insult your friends if you do not want