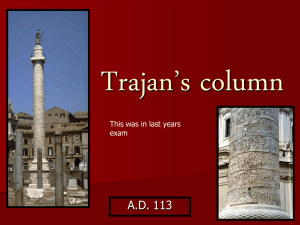

REMEMBERING TRAJAN IN FOURTH

advertisement